Anglo-Scottish border

| Anglo-Scottish border Crìochan Anglo-Albannach | |

|---|---|

The A1 road crossing the border between Scotland and England. Entry to Scotland is marked by three Scottish saltires and entry into England is marked by three flags of Northumberland. | |

| Characteristics | |

| Entities | |

| Length | 96 miles (154 km) |

| History | |

| Established | 25 September 1237 Signing of the Treaty of York |

| Current shape | 1999 Scottish Adjacent Waters Boundaries Order 1999 |

| Treaties | Treaty of York Treaty of Newcastle Treaty of Union 1706 |

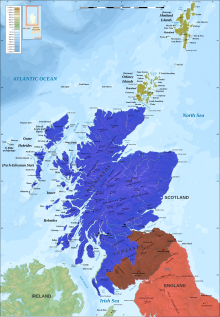

The Anglo-Scottish border (Scottish Gaelic: Crìochan Anglo-Albannach) is an internal border of the United Kingdom separating Scotland and England which runs for 96 miles (154 km) between Marshall Meadows Bay on the east coast and the Solway Firth in the west.

The Firth of Forth was the border between the Picto-Gaelic Kingdom of Alba and the Anglian Kingdom of Northumbria in the early 10th century. It became the first Anglo-Scottish border with the annexation of Northumbria by Anglo-Saxon England in the mid-10th century. In 973, the Scottish king Kenneth II attended the English king Edgar the Peaceful at Edgar's council in Chester. After Kenneth had reportedly done homage, Edgar rewarded Kenneth by granting him Lothian.[1] Despite this transaction, the control of Lothian was not finally settled and the region was taken by the Scots at the Battle of Carham in 1018 and the River Tweed became the de facto Anglo-Scottish border. The Solway–Tweed line was legally established in 1237 by the Treaty of York between England and Scotland.[2] It remains the border today, with the exception of the Debatable Lands, north of Carlisle, and a small area around Berwick-upon-Tweed, which was taken by England in 1482. Berwick was not fully annexed into England until 1746, by the Wales and Berwick Act 1746.[3]

For centuries until the Union of the Crowns, the region on either side of the boundary was a lawless territory suffering from the repeated raids in each direction of the Border Reivers. Following the Treaty of Union 1706, ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united Scotland with England and Wales to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, the Border forms the boundary of the two legal systems as the treaty between Scotland and England guaranteed the continued separation of English law and Scots law.[4] The age of marriage under Scots law is 16, while it is 18 under English law. The border settlements of Gretna Green to the west, and Coldstream and Lamberton to the east, were convenient for elopers from England who wanted to marry under Scottish laws, and marry without publicity.

The marine boundary was adjusted by the Scottish Adjacent Waters Boundaries Order 1999 so that the boundary within the territorial waters (up to the 12-mile (19 km) limit) is 90 metres (300 ft) north of the boundary for oil installations established by the Civil Jurisdiction (Offshore Activities) Order 1987.[5] The land border is near and roughly parallel to the 420 million-year-old Iapetus Suture.

History

[edit]

The border country, historically known as the Scottish Marches, is the area on either side of the Anglo-Scottish border including parts of the modern council areas of Dumfries and Galloway and the Scottish Borders, and parts of the English counties of Cumbria and Northumberland. It is a hilly area, with the Scottish Southern Uplands to the north, and the Cheviot Hills forming the border between the two countries to the south. From the Norman conquest of England until the reign of James VI of Scotland, who in the course of his reign became James I of England while retaining the more northerly realm, border clashes were common and the monarchs of both countries relied on Scottish Earls of March and Lord Warden of the Marches to defend and control the frontier region.

Second War of Scottish Independence

[edit]

In 1333, during the Second War of Scottish Independence, Scotland was defeated at the Battle of Halidon Hill and Edward III occupied much of the borderlands. Edward declared Edward Balliol the new King of Scots, in exchange for much of southern Scotland and absolute supplication, but this was not recognised by the majority of the Scottish nobility who remained loyal to David II and conflict continued.[6] By 1341, Perth and Edinburgh had been retaken by the Scots and Edward Balliol fled to England, effectively nullifying the supposed treaty. Edward would continue the war but would be unable to restore the puppet ruler Balliol to the throne and with the Treaty of Berwick (1357) Scottish independence was once again acknowledged with any pretence to territorial annexations dropped.

Clans

[edit]A 16th-century Act of the Scottish Parliament talks about the chiefs of the border clans, and a late 17th-century statement by the Lord Advocate uses the terms "clan" and "family" interchangeably. Although Lowland aristocrats may have increasingly liked to refer to themselves as "families", the idea that the term "clan" should be used for Highland families alone is a 19th-century convention.[7]

Historic Border clans include the following: Armstrong, Beattie, Bannatyne, Bell, Briar, Carruthers, Douglas, Elliot, Graham, Hedley of Redesdale, Henderson, Hall, Home or Hume, Irvine, Jardine, Johnstone, Kerr, Little, Moffat, Nesbitt, Ogilvy, Porteous, Robson, Routledge, Scott, Thompson, Tweedie.

Scottish Marches

[edit]During late medieval and early modern eras—from the late 13th century, with the creation by Edward I of England of the first Lord Warden of the Marches to the early 17th century and the creation of the Middle Shires, promulgated after the personal union of England and Scotland under James VI of Scotland (James I of England)—the area around the border was known as the Scottish Marches.

For centuries the Marches on either side of the boundary was an area of mixed allegiances, where families or clans switched which country or side they supported as suited their family interests at that time, and lawlessness abounded. Before the personal union of the two kingdoms under James, the border clans would switch allegiance between the Scottish and English crowns depending on what was most favourable for the members of the clan. For a time a powerful local clan dominated a region on the border between England and Scotland. It was known as the Debatable Lands and neither monarch's writ was heeded.[citation needed]

Middle Shires

[edit]Following the 1603 Union of the Crowns, King James VI & I decreed that the Borders should be renamed 'the Middle Shires'. In the same year the King placed George Home, 1st Earl of Dunbar in charge of the pacification of the borders. Courts were set up in the towns of the Middle Shires and known reivers were arrested. The more troublesome and lower classes were executed without trial; known as "Jeddart justice" (after the town of Jedburgh in Roxburghshire). Mass hanging soon became a common occurrence. In 1605 he established a joint commission of ten members, drawn equally from Scotland and England, to bring law and order to the region. This was aided by statutes in 1606 and 1609, first to repeal hostile laws on both sides of the border, and then to more easily prosecute cross-border raiders.[8] Reivers could no longer escape justice by crossing from England to Scotland or vice versa.[9] The rough-and-ready Border Laws were abolished and the folk of the middle shires found they had to obey the law of the land like all other subjects.

In 1607 James felt he could boast that "the Middle Shires" had "become the navel or umbilic of both kingdoms, planted and peopled with civility and riches". After ten years King James had succeeded; the Middle Shires had been brought under central law and order. By the early 1620s the Borders were so peaceful that the Crown was able to scale down its operations.

Despite these improvements, the Joint Commission continued its work, and as late as 25 September 1641 under King Charles I, Sir Richard Graham, a local laird and English MP, was petitioning the Parliament of Scotland "for regulating the disorders in the borders".[10] Conditions along the border generally deteriorated during the Commonwealth and Protectorate periods, with the development of Moss-trooper raiders. Following the Restoration, ongoing border lawlessness was dealt with by reviving former legislation, renewed continually in eleven subsequent acts, for periods ranging from five to eleven years, up until the late 1750s.[8]

Controversial territories

[edit]The Debatable Lands

[edit]

The Debatable Lands lay between Scotland and England to the north of Carlisle,[11] the largest population centre being Canonbie.[12] For over three hundred years the area was effectively controlled by local clans, such as the Armstrongs, who successfully resisted any attempt by the Scottish or English governments to impose their authority.[13] In 1552 commissioners met to divide the land in two: Douglas of Drumlanrigg leading the Scots; Lord Wharton leading the English; the French ambassador acting as umpire. The Scots' Dike was built as the new frontier, with stones set up bearing the arms of England and of Scotland.[14][15]

Berwick-upon-Tweed

[edit]Berwick is famous for its hesitation over whether it is part of Scotland or England.[16] Berwickshire is in Scotland while the town is in England, although both Berwick and the lands up to the Firth of Forth belonged to the Kingdom of Northumbria in the Early Middle Ages.[17] The town changed hands more than a dozen times before being finally taken by the English in 1482, though confusion continued for centuries. The Wales and Berwick Act 1746 clarified the status of Berwick as an English town. In the 1950s the artist Wendy Wood moved the border signs south to the middle of the River Tweed as a protest.[18] In 2008 SNP MSP Christine Grahame made calls in the Scottish Parliament for Berwick to become part of Scotland again.[19] Berwick's MP Anne-Marie Trevelyan has resisted any change, arguing that: "Voters in Berwick-upon-Tweed do not believe it is whether they are in England or Scotland that is important."[20]

The Ba Green

[edit]At the River Tweed the border runs down the middle of the river, however between the villages of Wark and Cornhill the Scottish border comes south of the river to enclose a small riverside meadow of approximately 2 to 3 acres (about a hectare). This piece of land is known as the Ba Green. It is said locally that every year the men of Coldstream (to the North of the river) would play mob football with the men of Wark (to the South of the river) at Ba, and the winning side would claim the Ba Green for their country. As Coldstream grew to have a larger population than Wark, the Coldstream men always defeated the Wark men at the game, and so the land became a permanent part of Scotland.[21][22][23]

Hadrian's Wall misconception

[edit]

It is a common misconception that Hadrian's Wall marks the Anglo-Scottish border. The wall lies entirely within England and has never formed this boundary.[24][25] While in the west, at Bowness-on-Solway, it is less than 0.6 mi (1.0 km) south of the border with Scotland, in the east it is as much as 68 miles (109 km) away.

For centuries the wall was the boundary between the Roman province of Britannia (to the south) and the Celtic lands of Caledonia (to the north). However Britannia occasionally extended as far north as the later Antonine Wall. Furthermore, to speak of England and Scotland at any time prior to the ninth century is anachronistic; such nations had no meaningful existence during the period of Roman rule.

"Hadrian's Wall" is nonetheless often used as an informal reference to the modern border, often semi-humorously.[a]

Migration

[edit]Cumbria and Northumberland have amongst the largest Scottish-born communities in the world outside Scotland. 16,628 Scottish-born people were residing in Cumbria in 2001 (3.41% of the county's population) and 11,435 Scottish-born people were residing in Northumberland (3.72% of the county's population); the overall percentage of Scottish-born people in England is 1.62%.[26] Consequently, almost 9% of Scotland's population is English-born (459,486), with higher than average percentages of English-born people in both Dumfries & Galloway and the Scottish Borders council areas, respectively, reaching as high as 35% or higher English-born.[27]

List of places on the border, or associated with it

[edit]

On the border

[edit]England

[edit]

Cumbria

[edit]Northumberland

[edit]

- Ancroft

- Barmoor Castle

- Barrow Burn

- Beadnell

- Belford

- Berwick-upon-Tweed, and the former borough

- Bowsden

- Branxton

- Byrness

- Carham

- Catcleugh Reservoir

- Chatton

- Chillingham Castle

- Cornhill-on-Tweed

- Crookham

- Doddington

- Duddo and Duddo Tower

- Etal and Etal Castle

- Fowberry Tower

- Goswick

- Greystead

- Haggerston and Haggerston Castle

- Horncliffe

- Howtel

- Islandshire

- Kielder, Kielder Forest and Kielder Water

- Kilham

- Kirknewton

- Lilburn and Lilburn Tower

- Lindisfarne and Lindisfarne Castle

- Lowick

- Middleton

- Milfield

- Mindrum

- Norham and Norham Castle

- North Sunderland

- Otterburn

- Redesdale & River Rede

- Scremerston

- Spittal

- Twizell Castle

- Wark on Tweed

- Wooler

- Yeavering

Scotland

[edit]

Dumfries and Galloway

[edit]Borders

[edit]- Allanton

- Ayton

- Birgham

- Cessford Castle

- Chirnside

- Coldstream

- Dinlabyre

- Duns

- Eccles

- Eden Water

- Edgerston

- Ednam

- Edrington

- Edrom

- Ettrick

- Eyemouth

- Fogo

- Foulden

- Galashiels

- Hawick

- Hermitage and Hermitage Castle

- Hilly Linn

- Hilton

- Hume Castle

- Hutton

- Jedburgh

- Kelso

- Kirk Yetholm & Town Yetholm

- Ladykirk

- Lamberton

- Leitholm

- Liddesdale

- Mordington

- Morebattle

- Mowhaugh

- Newcastleton

- Oxnam

- Paxton

- Roxburgh and Roxburgh Castle

- Saughtree

- Selkirk

- Southdean

- Swinton

- Timpanheck

- Whitsome

Rivers

[edit]Mountains

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Three examples of a humorous reference to Hadrian's Wall:

- "and there are plans for an electrified fence along Hadrian's Wall to prevent emigration from the rump republic" (Sandbrook 2012 quoting Robert Moss in The Collapse of Democracy (1975));

- "a situation that the (notional) electrification of Hadrian's Wall is unlikely to change" (Ijeh 2014);

- A cartoon: "Hadrian's Wall Extension Plan" showing an extension of Hadrian's Wall around the coastline of England and Wales (Hughes 2014).

References

[edit]- ^ Rollason, David W. (2003). Northumbria, 500 – 1100: Creation and Destruction of a Kingdom. Cambridge University Press. p. 275. ISBN 0521813352.

- ^ "Scotland Conquered, 1174-1296". The National Archives. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ Blackstone, William; Stewart, James (1839). The rights of persons, according to the text of Blackstone. Edmund Spettigue. p. 92.

- ^ Collier, J.G. (2001). Conflict of Laws (PDF). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-521-78260-0.

For the purposes of the English conflict of laws, every country in the world which is not part of England and Wales is a foreign country and its foreign laws. This means that not only totally foreign independent countries such as France and Russia... are foreign countries but also British Colonies such as the Falkland Islands. Moreover, the other parts of the United Kingdom—Scotland and Northern Ireland—are foreign countries for present purposes, as are the other British Islands, the Isle of Man, Jersey, and Guernsey.

- ^ Scottish Parliament Official Report 26 April 2000[permanent dead link]. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ William Hunt, ed. (1905). The Political History of England, Volume 3.

- ^ Agnew, Crispin (13 August 2001). "Clans, Families and Septs". Electric Scotland. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ a b See: Border Reivers#Legislation

- ^ Act anent fugitive persones of the borders to the in country (1609): Forsamekle as the kingis majestie is resolved to purge the mydele schyres of this isle, heirtofoir callit the bordouris of Scotland and England, of that barbarous crueltie, wickednes and incivilitie whilk be inveterat custome almaist wes become naturall to mony of the inhabitantis thairof... (Translated: Forasmuch as the king's majesty is resolved to purge the middle shires of this isle, heretofore called the borders of Scotland and England, of that barbarous cruelty, wickedness and incivility which by inveterate custom almost was become natural to many of the inhabitants thereof...)

- ^ Petition of Sir Richard Graham regarding the middle shires: I am desired by Sir Richard Graham to move your majesty and this house of parliament that some present course may be taken for regulating the disorders that are now in the middle shires, this being the best time whilst the English commissioners are here that order may be given to the commissioners of both kingdoms to call the border landlords now in town to inform themselves what course has been formerly held for the suppressing of disorder and apprehending of felons and fugitives.

- ^ The County Histories of Scotland, Volume 5. Scotland: W. Blackwood and Sons. 1896. pp. 160–162. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Dan O'Sullivan (2016). The Reluctant Ambassador: The Life and Times of Sir Thomas Chaloner, Tudor Diplomat. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445651651. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ The History of Liddesdale, Eskdale, Ewesdale, Wauchopedale and the ..., Volume 1 By Robert Bruce Armstrong pp. 181–2

- ^ "Debatable Land". www.geog.port.ac.uk.

- ^ "A short history of the Debatable Lands and Border Reivers". www.scotsman.com.

- ^ New Statesman. 11 Sep 2014. The Scottish referendum means Berwick-upon-Tweed faces an uncertain future. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ Kerr, Rachel (8 October 2004). "A tale of one town". BBC News. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

- ^ "Swapping sides: the English town that wants to be Scottish". The Independent. 13 February 2008. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

It was Berwick which became the focal point for the direct action of one of the first modern Scottish nationalists, Wendy Wood in the 1950s. Controversially...she was regularly arrested for moving the border signs over the Tweed.

- ^ "'Return to fold' call for Berwick". BBC News. 10 February 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- ^ "Berwick-upon-Tweed: English or Scottish?". BBC News. 1 May 2010.

- ^ Crofton, Ian (2012). A dictionary of Scottish phrase and fable. Edinburgh: Birlinn. p. 25. ISBN 9781841589770.

- ^ Moffat, Alistair (1 July 2011). The Reivers: The Story of the Border Reivers. Birlinn. ISBN 9780857901156.

- ^ "(Showing Scottish border south of the Tweed) - Berwickshire Sheet XXIX.SW (includes: Coldstream) -". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ English Heritage. 30 Surprising Facts About Hadrian's Wall Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ^ Financial Times. Borders held dear to English and Scots Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ^ "Neighbourhood Statistics Home Page". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ "Are English settlers in the Highlands nicer than those in the Borders and if so why?". 22 May 2019.

References

[edit]- Hughes, Alex (5 September 2014), Hadrian's Wall Extension Plan, alexhughescartoons.co.uk, retrieved 15 December 2014

- Ijeh, Ike (27 August 2014), "What did Scotland do for architecture?", Building Design Online, retrieved 7 October 2016

- Sandbrook, Dominic (2012), "Chapter 6: Could it happen here?", Seasons in the Sun: The Battle for Britain, 1974–1979 (illustrated ed.), UK: Penguin, p. about 214, ISBN 9781846140327

Further reading

[edit]- Aird, W.M. (1997) "Northern England or southern Scotland? The Anglo-Scottish border in the eleventh and twelfth centuries and the problem of perspective" In: Appleby, J.C. and Dalton, P. (Eds) Government, religion and society in Northern England 1000-1700, Stroud : Sutton, ISBN 0-7509-1057-7, p. 27–39

- Crofton, Ian (2014) Walking the Border: A Journey Between Scotland and England, Birlinn

- Readman, Paul (2014). "Living a British Borderland: Northumberland and the Scottish Borders in the Long Nineteenth Century". Borderlands in World History, 1700–1914. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 169–191. ISBN 978-1-137-32058-2.

- Robb, Graham (2018) The Debatable Land: The Lost World Between Scotland and England, Picador

- Robson, Eric (2006) The Border Line, Frances Lincoln Ltd.

- Sparrow, W. S. and Crockett, W. S. (1906). In the Border Country, Hodder & Stoughton, London

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Border between England and Scotland at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Border between England and Scotland at Wikimedia Commons

- The Border Clans and their Emigration to America at Hodgson Clan

- The world's oldest border?, from Jay Foreman's "Map Men" series