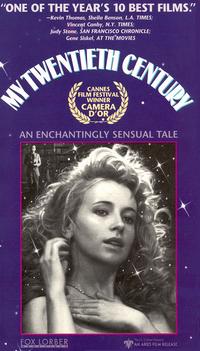

My 20th Century

| My 20th Century | |

|---|---|

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Ildikó Enyedi |

| Written by | Ildikó Enyedi |

| Produced by | Archy Dolder Norbert Friedländer Gábor Sarudi Andrej Schwartz |

| Starring | Dorota Segda |

| Cinematography | Tibor Máthé |

| Edited by | Mária Rigó |

| Music by | László Vidovszky |

| Distributed by | Aries Films (United States) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 102 minutes |

| Countries | Hungary West Germany Cuba |

| Language | Hungarian |

My 20th Century (Hungarian: Az én XX. századom) is a 1989 Hungarian comedy-drama science fiction film written and directed by Ildikó Enyedi. It premiered at the Toronto Festival of Festivals. Enyedi won the Golden Camera award at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival.[1] The film was selected as the Hungarian entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 62nd Academy Awards, but was not accepted as a nominee.[2] The film was chosen to be part of the New Budapest Twelve, a list of Hungarian films considered the best in 2000.[3]

Plot

[edit]In Budapest in 1880, two twin sisters, Dóra and Lili, are born. After their mother dies, the twins support themselves by selling matches in the street. When they fall asleep one night, two men take their matches and, after a coin flip, each takes a girl and they go their separate ways.

On New Year's Eve 1900, Dóra, a drifter, finds herself aboard the Orient Express trying to scam two men out of money. In Austria, Lili, now a revolutionary, boards the train where she is briefly seen by Dóra, who is drunk and instantly forgets her.

At a library, Lili encounters Z, a man who will not stop staring at her. The two become acquainted and Z falls in love with her, but Lili, who is carrying a bomb which she plans to use to kill the minister of the interior, remains focused on her politics even when her plot fails.

Later, Z encounters Dóra on a boat. Believing her to be Lili, he gives her the number of his cabin where she robs him and the two later have sex.

When Z and Lili meet again, he takes her to his apartment. Lili, who had previously sexually rejected Z, apologizes to him and tells him she regrets her previous decision. Believing that Lili is apologizing for robbing him, Z takes her to his apartment and they have sex. The following evening Lili attacks the minister with a bomb, but after looking into his eyes she blows out the bomb and runs away. Seeking refuge from a crowd of police, Lili hides in a fun house where, turning a corner, she sees Dóra. Z finds his way there as well and briefly sees them both together before the two run away from him.

Cast

[edit]- Dorota Segda - Dóra / Lili / Anya (as Dorotha Segda)

- Oleg Yankovskiy - Z

- Paulus Manker - Otto Weininger

- Péter Andorai - Thomas Edison

- Gábor Máté - K

- Gyula Kéry - ékszerész (as Kéri Gyula)

- Andrej Schwartz - Segéd

- Sándor Téri - Huszár (as Téry Sándor)

- Sándor Czvetkó - Young anarchist

- Endre Koronczi - Liftboy

- Ágnes Kovács & Eszter Kovács - Baby twins

Reception

[edit]

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 100%, based on 9 reviews.[4] In one positive review, Silent London wrote that "the cinema is just one of the 20th-century ideas that illuminate this film – from politics through to science, technology and transport. Enyedi's film has the capacity to make ideas and inventions that are now familiar seem new again, to imbue them with the sense of wonder and magic that they once held.[5] Peter Bradshow wrote in The Guardian that "My 20th Century is a jeu d’ésprit, a whimsical erotic fantasia of central Europe, a millennial meditation on modernity, all in black-and-white and infused with the spirit of early cinema."[6]

Darragh O'Donoghue, in film magazine Cineaste, described the film as "a true masterpiece of 'domesticated sci-fi'" and "one of the great debuts in film history, as formally daring, visually inventive, and thematically complex as Citizen Kane." "Here science is treated as a source of wonder, magic, fantasy, utopianism... Every sequence, every shot in this film is a mini-epic in itself—cinematography, composition, and sound shaped with an intensity across the entire film that is rare in the cinema."[7]

Cinematic analysis

[edit]Toronto International Film Festival curator Dorota Lech wrote that My 20th Century was a "mischievous fairy tale of synchronicity and fin-de-siècle wonder" and established Enyedi's reputation as "an early pioneer of female science-fiction cinema and a master of labyrinthian storytelling." My 20th Century, she goes on, has "a narrative concerned with both universal concepts and material dilemmas, cutting across space and time, sprinkled with irony, symbolism, and documentary realism" and "centers on the twin origins of modernity and cinema, both born of electricity." It reminds the viewer that "our 20th century is undoubtedly one of paradoxes and we, like the dog connected to electrodes, know nothing of the universe beyond our own laboratory. ... These diverging narrative threads of male scientific triumph over nature and female biological capability are prodded and reflected in a kaleidoscope of turn-of-the-century events." The film is "a pointed critique of man's arrogance through his pursuit for truth and his assumed infallibility of science in its infantile state."[8]

Film scholar Jonathan Owen writes that My 20th Century is "a story of the twentieth century itself and of its bold early developments - technological, political and cultural - in all their magic, promise, and danger" and calls it a "meditation on technological enlightenment that is quite literally luminous." He says that the opening sequence is "clownish yet a little ominous" and "sets the tone for a film that will pay homage to the exuberance of early cinema while musing on the mixed blessings of a machine-dominated modernity." Enyedi, Owen writes, "is as much engaged with the unrealized possibilities of the twentieth century as with the shape it actually took" and he explains that the twins are contrary visions of the twentieth century. Owen explains that the pigeon at the end of the film "conveys the lost romance of pre-technological communication" and "recalls the failure of modern technology to realize its utopian potential and achieve genuine global and social connection." Owen identifies a number of silent films that are referenced in My 20th Century, including 1921's Orphans of the Storm (which stars Lillian and Dorothy Gish, whose names are similar to Lili and Dóra's), 1926's Now You Tell One, and 1928's The Little Match Girl.[9]

New York Times film critic Judy Stone wrote that the film is about "the dreams and possibilities that existed in the 19th century and came true in the 20th. The inventions of electric light, flight, the telephone, movies, radio, television and computer microchips are now taken for granted, but... science has also diminished our sense of the miraculous." Stone interviewed Enyedi, who stated "The people who achieved those inventions could make them because they were not afraid. They didn't believe in governments or in political ideologies, but they were still able to believe in themselves." In warning that those technologies may pose dangers to the world, Enyedi said "Our age has become overtechnical and soulless. Science has lost its moral basis. When I was planning the film, I thought about European culture -- where it is now and what will happen."[10]

My 20th Century was featured in Mark Cousins' documentary Women Make Film in the Sci-Fi and Time episodes. In the Sci-Fi episode, narrator Thandiwe Newton states that the film is "one of the most unusual in the sci-fi genre", that it goes beyond "future or parallel worlds, places of escape or veiled versions of our own malaise", and that Enyedi "shows that sci-fi has no bounds."[11]

See also

[edit]- List of submissions to the 62nd Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of Hungarian submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

References

[edit]- ^ "Festival de Cannes: My 20th Century". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ^ Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

- ^ "Új Budapesti Tizenkettő". Filmvilág. XLIII (3): 2. March 2000.

- ^ "My 20th Century (1989)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "MY 20TH CENTURY: ILDIKO ENYEDI MAKES THE FAMILIAR SEEM NEW AGAIN". Silent London. 18 October 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (5 October 2018). "My 20th Century review – tales of an adventuress and an anarchist". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ O'Donoghue, Darragh. "The 2017 Thessaloniki International Film Festival". Cineaste. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Lech, Dorota. Synchronicities, Dichotomies, and the Unstated Female Gaze (Media notes). Kino Lorber.

- ^ Owen, Jonathan. A Double Vision of Modernity: My 20th Century (Media notes). Second Run.

- ^ Stone, Judy (4 November 1990). "FILM; Twins on Different Tracks Through the Years". New York Times. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Women Make Film.

External links

[edit]- 1989 films

- 1989 independent films

- 1980s avant-garde and experimental films

- 1980s science fiction comedy-drama films

- West German films

- Hungarian black-and-white films

- Hungarian independent films

- Hungarian science fiction films

- Cuban comedy-drama films

- 1980s Hungarian-language films

- Films directed by Ildikó Enyedi

- Caméra d'Or winners

- 1989 comedy-drama films

- Hungarian comedy-drama films

- Films set on trains

- 1989 science fiction films