Ellen Wilkinson

Ellen Wilkinson | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

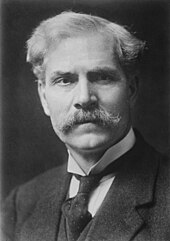

Wilkinson in 1924 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Minister of Education | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 3 August 1945 – 6 February 1947 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Clement Attlee | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Richard Law | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | George Tomlinson | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Labour Party | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 4 January 1944 – 3 August 1945 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader | Clement Attlee | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | George Ridley | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Harold Laski | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Ellen Cicely Wilkinson 8 October 1891 Manchester, England | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 6 February 1947 (aged 55) London, England | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Labour | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations | Communist Party of Great Britain (1920–1924) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | University of Manchester (BA) | ||||||||||||||||||||

Ellen Cicely Wilkinson (8 October 1891 – 6 February 1947) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Minister of Education from July 1945 until her death.

Earlier in her career, as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Jarrow, she became a national figure when she played a prominent role in the 1936 Jarrow March of the town's unemployed to London to petition for the right to work. Although unsuccessful at that time, the March provided an iconic image for the 1930s and helped to form post-Second World War attitudes to unemployment and social justice.

Wilkinson was born into a poor though ambitious Manchester family and she embraced socialism at an early age. After graduating from the University of Manchester, she worked for a women's suffrage organisation and later as a trade union officer. Inspired by the Russian Revolution of 1917, Wilkinson joined the British Communist Party, and preached revolutionary socialism while seeking constitutional routes to political power through the Labour Party. She was elected Labour MP for Middlesbrough East in 1924, and supported the 1926 General Strike.

In the 1929–31 Labour government, she served as Parliamentary Private Secretary to the junior Health Minister. She made a connection with a young female member and activist Jennie Lee. Following her defeat at Middlesbrough in 1931, Wilkinson became a prolific journalist and writer, before returning to parliament as Jarrow's MP in 1935. She was a strong advocate for the Republican government in the Spanish Civil War, and made several visits to the battle zones.

During the Second World War, Wilkinson served in Churchill's wartime coalition as a junior minister, mainly at the Ministry of Home Security, where she worked under Herbert Morrison. She supported Morrison's attempts to replace Clement Attlee as the Labour Party's leader; nevertheless, when he formed his postwar government, Attlee appointed Wilkinson as Minister of Education. By this time, her health was poor, a legacy of years of overwork.

She saw her main task in office as the implementation of the wartime coalition's Education Act 1944, rather than the more radical introduction of comprehensive schools favoured by many in the Labour Party. Much of her energy was applied to organising the raising of the school-leaving age from 14 to 15. During the exceptionally cold weather of early 1947, she succumbed to a bronchial disease, and died after an overdose of medication, which the coroner at her inquest declared was accidental.

Life

[edit]Background, childhood and education

[edit]Early years

[edit]

Ellen Wilkinson was born on 8 October 1891, at 41 Coral Street in the Manchester district of Chorlton-on-Medlock.[2] She was the third child and second daughter of Richard Wilkinson, a cotton worker who became an insurance agent, and his wife, Ellen, née Wood.[3] Richard Wilkinson was a pillar of his local Wesleyan Methodist church, and combined a strong sense of social justice with forthright views on self-help; rather than espousing working-class solidarity his view, according to Ellen, was: "I have pulled myself out of the gutter, why can't they?"[4] Entirely self-educated, he ensured that his children received the best schooling available, encouraged them to read widely, and inculcated strong Christian principles.[5][6]

At the age of six Ellen began attending what she described as "a filthy elementary school with the five classes in one room".[7] A series of childhood illnesses kept her at home for two years, but she used the time learning to read.[8] On her return to school she made rapid progress, and at the age of 11 won a scholarship to Ardwick Higher Elementary Grade School.[9] Outspoken and often rebellious,[10] after two years she transferred to Stretford Road Secondary School for Girls, an experience she later remembered as "horrid and unmanageable".[11] She made up for the school's shortcomings by reading, with her father's encouragement, the works of Haeckel, Thomas Huxley and Darwin.[12]

Teaching was one of the few careers then open to educated working-class girls, and in 1906 Ellen won a bursary of £25 that enabled her to begin her training. For half the week she attended the Manchester Day Training College, and during the other half taught at Oswald Road Elementary School. Her classroom approach—she sought to interest her pupils, rather than impose learning by rote—led to frequent clashes with her superiors, and convinced her that her future did not lie in teaching.[13][14] At the college, where she was encouraged to read more widely and to engage with the issues of the day, she discovered socialism through the works of Robert Blatchford. By this time she was impatient with religion; socialism provided a timely and attractive substitute.[15] At 16 she joined the Longsight branch of the Independent Labour Party (ILP), and at one of her first branch meetings encountered Katherine Bruce Glasier, whose crusading brand of socialism made a deep impact.[11]

Thirty years later Wilkinson told her colleague George Middleton that Glasier had "brought me into the Socialist movement ... It always makes me humble to think of her indomitable courage".[16] After meeting the suffragist Hannah Mitchell, Wilkinson took up the cause of women's suffrage, the major women's rights issue of the day. Although initially engaged in everyday tasks such as distributing leaflets and putting up posters,[17][18] she made a considerable impression on Mitchell, who later remembered her as "brilliant and gifted".[19]

University

[edit]

Determined to carve a career for herself outside teaching, in 1910 Wilkinson sat for and won the Jones Open History Scholarship, which gave her a place at Manchester University.[20] There, she found many opportunities to extend her political activities. She joined the university's branch of the Fabian Society, and eventually became its joint secretary.[18] She continued her suffragist work by joining the Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage, where she impressed Margaret Ashton, the first woman member of Manchester City Council, by her efforts in the North Manchester and Gorton constituencies.[21]

Through these and other campaigning activities Wilkinson met many of the contemporary leaders of the radical left—the veteran campaigner Charlotte Despard, the ILP leader William Crawford Anderson, and Beatrice and Sidney Webb among others.[22] She also came under the influence of Walton Newbold, an older student who later became the United Kingdom's first Communist MP. The two were briefly engaged, and although this was soon broken off, they remained close political associates for many years.[23]

In her final year at university Wilkinson was co-opted to the executive committee of the University Socialist Federation (USF), an inter-institutional organisation formed to bring together socialist-minded students from all over the country. This brought her new contacts, who would typically meet at Fabian summer schools to hear lectures by ILP leaders such as Ramsay MacDonald and Arthur Henderson, and trade union activists such as Ben Tillett and Margaret Bondfield. Amid these distractions she continued to study hard, and won several prizes. In the summer of 1913 she sat her finals and was awarded her BA degree—not the First Class honours that her tutors had predicted, but an Upper Second. Wilkinson rationalised thus: "I deliberately sacrificed my First ... to devote my spare time to a strike raging in Manchester".[22][24][n 2]

Early career

[edit]Trade union organiser

[edit]On leaving university in June 1913, Wilkinson became a paid worker for the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS).[25] She helped to organise the Suffrage Pilgrimage of July 1913, when more than 50,000 women marched from all over the country to a mass rally in Hyde Park, London.[26][27] She began to develop a fuller understanding of the mechanics of politics and campaigning, and became an accomplished speaker, able to hold her own even in the most hostile public meetings.[28]

When the First World War began in August 1914, Wilkinson, like many in the Labour movement, condemned it as an imperialist exercise that would result in the deaths of millions of workers. Nevertheless, she took the role of honorary secretary of the Manchester branch of the Women's Emergency Corps (WEC), a body which found suitable war work for women volunteers. With the advent of war the NUWSS became divided between pro-war and pro-peace factions. They ultimately separated, the peacemongers (including Wilkinson's Manchester branch) eventually aligning themselves with the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WIL),[29] and included Agnes Harben.[30]

With little suffrage activity to organise, Wilkinson looked for another job, and in July 1915 was appointed as a national organiser for the Amalgamated Union of Co-operative Employees (AUCE), with particular responsibility for the recruitment of women into the union.[31] In this post she fought for equal pay for equal work, and for the rights of unskilled and lower-paid workers when these interests conflicted with those of the higher-paid craft unions.[32] She organised a series of strikes to attain these goals with notable successes in Carlisle, Coatbridge, Glasgow and Grangemouth.[33] She was less successful in managing a lengthy dispute at the Longsight print works in Manchester, in the summer of 1918, where opponents described her tactics as "unreasonable guerrilla warfare".[34]

As a result of her actions Wilkinson briefly lost her job at the union, only to be swiftly reinstated after protests by members and after apologising for her role in the strike.[35][36] From 1918 she served as her union's nominee on several Trade Boards—national consultative bodies which attempted to set minimum wage rates for low-paid workers.[37] In 1921 AUCE amalgamated with the National Union of Warehouse and General Workers to form the National Union of Distributive and Allied Workers (NUDAW).[38]

Wilkinson's work for the union brought new alliances, and useful new friendships—including one with John Jagger, the union's future president.[39] She remained an active Fabian, and after the Fabian Research Department became the Labour Research Department in 1917, served on the new body's executive committee.[40] Through these connections she became a member of the National Guilds League (NGL), an organisation that promoted industrial democracy, workers' control and producer associations in a national system of guilds.[41] She maintained her connection with the WIL, whose 1919 conference adopted a non-pacifist stance that justified armed struggle as a means of defeating capitalism.[42] After visiting Ireland for the WIL in 1920 she became an outspoken critic of the British government's actions there, in particular its use of the "Black and Tans" as a paramilitary force. She gave evidence about the conduct of British forces in Ireland at the Congressional Committee of Investigation in Washington in December of that year.[43] She called for an immediate truce and the release of republican prisoners.[44][45][n 3]

Communism

[edit]"[We] read with incredulous eyes that the Russian people, the workers, the soldiers, and peasants, had really risen and cast out the Tsar and his government ... we did no work at all in the office, we danced around tables and sang ... Everyone with an ounce of liberalism in his composition rejoiced that tyranny had fallen".

Along with many others in the Labour movement, Wilkinson's attitudes were radicalised by the Russian Revolution of 1917. She saw communism as the shape of the future, and when the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was formed in the summer of 1920,[48] Wilkinson was one of a group of ILP members with Marxist leanings who became founder members.[49] For the next few years the CPGB was the main focus of her political activity, although she kept her membership in the Labour Party, which at the time accepted dual CPGB/Labour memberships.[50]

In 1921 Wilkinson attended the Red International of Labour Unions Congress and the Second Congress of Communist Women in Moscow,[51][52] where she met several Russian communist leaders, including the Defence Minister Leon Trotsky, and Nadezhda Krupskaya, the educationist who was Lenin's wife; Wilkinson considered Krupskaya's speech the best at the Congress.[48] The main outcome of the gathering was the foundation of the Red International of Labour Unions, often known as the "Profintern". The aim of this organisation was to seek revolutionary change through industrial action, leading to the overthrow of world capitalism.[53] At home, although she failed to persuade her union, NUDAW, to affiliate to the Profintern,[51]

Wilkinson continued to promote Russian achievements, especially its emancipation of women workers.[42] In November 1922, at a meeting celebrating the fifth anniversary of the Russian Revolution, Wilkinson said that the Russian people could look forward with hope, and asked whether the same could be said of the people condemned to live their lives in the slums of Manchester.[54] However, Wilkinson found herself increasingly at odds with communists in Manchester, over the party's industrial and wider international strategies.[55]

Seeking elective office

[edit]Wilkinson was an early and lifetime supporter of the National Council of Labour Colleges, established in 1921 with NUDAW backing with the aim of educating working-class students in working-class principles.[56][57] She became a NUDAW-sponsored parliamentary candidate, and in 1923, while still a CPGB member, sought nomination as the Labour Party's parliamentary candidate for the Gorton constituency.[50] She was unsuccessful, but in November 1923 the Gorton ward elected her to Manchester City Council;[3] Hannah Mitchell, her co-worker in prewar suffrage campaigns, was a fellow councillor.[58] In her short council career—she served only until 1926[3]—Wilkinson's main areas of concern were unemployment, housing, child welfare and education.[50]

When the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, called a general election for December 1923, Wilkinson was adopted as Labour's parliamentary candidate for Ashton-under-Lyne.[50] She made no secret of her Communist affiliations, stating that "we shall have only one class in this country, the working class".[59] In a three-way contest she came third, behind the Conservative and the Liberal candidate.[60] The general election resulted in a hung parliament, and a minority Labour government under Ramsay MacDonald took office.[61] During its short term in power, the Labour Party proscribed the Communist Party and outlawed dual membership.[50] Faced with a choice, Wilkinson left the CPGB, citing the party's "exclusive and dictatorial methods which make impossible the formation of a real left wing among the progressives of the Trade Unions and the Labour Party".[62] After this, she was selected as Labour's candidate for the constituency of Middlesbrough East.[63]

Middlesbrough MP

[edit]In opposition, 1924–29

[edit]

On 8 October 1924 MacDonald's Labour government resigned, after losing a confidence vote in the House of Commons.[64] The latter stages of the ensuing general election were dominated by the controversy surrounding the Zinoviev letter, which generated a "Red Scare" shortly before polling day and contributed to a massive Conservative victory.[65][66] Labour's representation in the House of Commons fell to 152, against the Conservatives' 415;[67] Wilkinson was the only woman elected in the Labour ranks,[n 4] winning Middlesbrough East with a majority of 927 over her Conservative opponent.[69]

Wilkinson's arrival in the House of Commons attracted considerable press comment, much of it related to her bright red hair and the vivid colours of her clothing.[70] She informed MPs: "I happen to represent in this House one of the heaviest iron and steel producing areas in the world—I know I do not look like it, but I do".[71] The Woman's Leader described her as a "vigorous, uncompromising feminist and an exceedingly tenacious, forcible and hard-headed politician".[72] A policeman once attempted to prevent Wilkinson from entering the House of Commons' smoking room based on her sex; Wilkinson responded, "I am not a lady - I am a Member of Parliament."[73] As an unofficial spokesperson for women's rights,[3] Wilkinson encouraged open debate on birth control, reprimanding Catholic trades unionist Bertha Quinn for calling it a 'crime' at a Labour Women's convention in 1925.[33] Wilkinson went on to achieve one of her first parliamentary victories in that same year, when she persuaded the government to correct anomalies affecting widows in its Pensions Bill.[74]

In March 1926, she combined with Lady Astor from the Conservative benches to attack the government's proposed decrease in expenditure on women's training centres.[75] The same month Wilkinson was elected President of the Manchester District branch of the Electrical Association for Women, Astor was the national president.[76] Wilkinson's ODNB biographer, Brian Harrison, acknowledges that while "women's issues" were often to the fore in her speeches, she was primarily a socialist rather than a feminist, and if forced to decide between them would have chosen the former.[3]

During the nine days' duration of the May 1926 General Strike, Wilkinson toured the country to press the strikers' case at meetings and rallies. She was devastated when the Trades Union Congress called off the strike. Early in June she joined George Lansbury and other leading Labour and union figures on the platform at an Albert Hall rally which raised around £1,200 for the benefit of the miners, who continued on strike despite the TUC decision.[77] Wilkinson's reflections on the strike were recorded in A Workers' History of the Great Strike (1927), which she co-authored with Raymond Postgate and Frank Horrabin,[78] and in a semi-autobiographical novel, Clash, which she published in 1929.[6][79] She also visited the United States in August 1926 to raise financial support for the miners, provoking criticism from the Conservative prime minister Baldwin who denied that the lockout was causing hardship.[80]

Throughout her career Wilkinson was an opponent of imperialism. In February 1927 she attended the Founding Congress of the League Against Imperialism in Brussels, where she met and befriended the Indian nationalist leader Jawaharlal Nehru.[81] In 1927 she was elected to the Labour Party's National Executive, which gave her a voice in the formulation of party policy.[82] Her advance was noted with approval by Beatrice Webb, who saw in her a future candidate for high office—ahead of more senior Labour women such as Margaret Bondfield and Susan Lawrence.[83] A tireless campaigner for women's equality, she challenged the caricature of voteless younger women as 'flappers'.[84] On 29 March 1928 Wilkinson voted in the House of Commons for the bill that became the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928, granting the vote to all women aged 21 or over.[85] During the debate she said: "[W]e are doing at last a great act of justice to the women of the country ... just as we have [previously] opened the door to the older women, tonight we are opening it to those who are just entering on the threshold of life and in whose hands is the new life of the future country that we are going to build".[86]

In government, 1929–31

[edit]In May 1929 Baldwin called a general election. As a member of Labour's National Executive, Wilkinson helped to draft her party's manifesto, although her preference for a list of specific policy proposals was overruled in favour of a lengthy statement of ideals and objectives.[87][88] In Middlesbrough she was re-elected with an increased majority over her Conservative and Liberal opponents.[60] Overall, Labour emerged from the election as the largest party, with 288 members (nine of whom were women),[87] while the Conservatives and Liberals won 260 and 59 respectively.[67][n 5] MacDonald formed his second minority administration, and included two women in ministerial posts: Margaret Bondfield as Minister of Labour and Susan Lawrence as Parliamentary Secretary (junior minister) at the Ministry of Health. Wilkinson was not given office, but was made Lawrence's Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS), an indication that she was marked for future promotion.[90][91][n 6]

Almost from its inception the second MacDonald administration was overwhelmed by the twin crises of rising unemployment and the world trade recession that followed the financial crash in the latter part of 1929. The Labour Party was divided; the Chancellor, Philip Snowden, favoured a strict curb on public expenditure, while others, including Wilkinson, believed that the problem was not over-production, but under-consumption. The solution, she argued, lay in increasing, not squeezing, the spending power of the poorest in society.[93] On the issue of unemployment, Wilkinson supported Oswald Mosley's "Memorandum", a plan for economic reconstruction and public works that was rejected by the government on the grounds of cost; Mosley resigned from the government in protest.[94][95][n 7]

"In a country that calls itself a democracy it really is a scandal that an unelected revising chamber should be tolerated, in which the Conservative Party has a permanent and overwhelming majority"

With Wilkinson's assistance, the Mental Treatment Act 1930 received the Royal Assent on 30 June 1930.[98] In the same year she co-sponsored a bill to limit shopworkers' hours to 48 a week, and poured scorn on Conservatives opposing the measure who seemed, she said, to think that all shop work was carried out in the "soothing atmosphere" and "exquisite scents" of Jermyn Street and Bond Street.[99] The bill was referred to a parliamentary committee, but got no further.[98] As the parliament progressed, it became increasingly difficult to promote social legislation in the face of the mounting financial crisis and the use by the Conservative-dominated House of Lords of its statutory delaying powers.[100][n 8]

The divisions in the Labour Party became more acute during 1931, as the government struggled to meet the May Report's recommended expenditure cuts of £97 million, the majority (£67 million) to be found from reductions in unemployment costs.[102] The government collapsed on 23 August 1931. To implement the required cuts, MacDonald and a small number of Labour MPs formed a National Government with the Conservatives and Liberals, while the bulk of the Labour Party, including Wilkinson, went into opposition.[103] In the general election that followed in October the Labour Party was utterly routed, retaining only 52 of its parliamentary seats.[67] In Middlesbrough East Wilkinson's vote was nearly the same as her 1929 total, but against a single candidate representing the National Government she was defeated by over 6,000 votes.[60]

Out of parliament, 1931–35

[edit]Wilkinson rationalised Labour's defeat in a Daily Express article, arguing that the party had lost because it was "not socialist enough", a theme she built on in numerous radical newspaper and journal articles.[104] In a less serious vein she published Peep at Politicians, a collection of humorous pen-portraits of parliamentary colleagues and opponents. She wrote that Winston Churchill was "cheerfully indifferent as to whether any new [ideas] he acquires match the collection he already possesses", and described Clement Attlee as "too fastidious for intrigue, and too modest for over-ambition".[105] Her second novel, The Division Bell Mystery, set in the House of Commons, was published in 1932; Paula Bartley, Wilkinson's biographer, acknowledges that Wilkinson was not a first-class novelist, but "the autobiographical topicality of [her] books made them very appealing".[104]

In 1932 Wilkinson was invited by the India League to join a small delegation, to report on conditions in India. During the three-month visit she met Gandhi, then in prison, and became convinced that his co-operation was essential to any prospect of peace in the subcontinent. On her return home she delivered her conclusions in an uncompromising report, The Condition of India, published in 1934.[106] She visited Germany shortly after Hitler came to power in 1933, and published a pamphlet, The Terror in Germany, that documented early incidents of Nazi outrage.[107] She collaborated with a refugee from Hitler's Germany, Edward Conze, to produce a major book, Why Fascism?, which condemned the Labour Party's gradualism and focus upon parliament as well as the failure of communist strategy, arguing for the need for grassroots workers' unity and revolution to check the threat of fascism across Europe.[108] Meanwhile, her parliamentary prospects had been revived by her selection as Labour candidate for Jarrow, a Tyneside shipbuilding town.[109] Jarrow had been devastated early in the 1930s by the run-down and closure of Palmers shipyard, the town's main source of employment. Early in 1934 Wilkinson led a deputation of Jarrow's unemployed to meet the prime minister, MacDonald, in his nearby Seaham constituency, and received sympathy but no positive action.[110][n 9] She was unimpressed by the government's Special Areas Act, passed late in 1934 and designed to assist distressed areas such as Jarrow; she thought the legislation provided inadequate funding, and benefited employers more than workers.[110][n 10]

Jarrow MP

[edit]Jarrow March

[edit]

In the November 1935 general election the National Government, led by Baldwin since MacDonald's retirement earlier that year, won convincingly, although Labour increased its House of Commons representation to 158.[67] Wilkinson was returned at Jarrow with a majority of 2,350.[60] Although the poverty in the town was acute, there were hopes that its chronic unemployment would shortly be alleviated by the erection of a large steelworks on the derelict shipyard site.[114] However, the scheme was opposed by the steelmasters represented by the British Iron and Steel Federation (BISF), who thought that any increase in steel production should be handled by expanding their existing facilities.[115] On 30 June 1936 Wilkinson asked Walter Runciman, the responsible minister, "to induce the Iron and Steel Federation to pursue a less selfish policy than it is pursuing at present".[116] Her request was ignored, and the matter delayed indefinitely by the appointment of a committee to consider the general development of the iron and steel industry—a committee, a Times letter-writer noted, dominated by BISF members.[117] A deputation from Jarrow's town council met Runciman to protest against the decision, but were told that "Jarrow must find its own salvation."[118][119]

According to Wilkinson, Runciman's dismissive phrase "kindled the town".[119] Under the general leadership of its chairman, David Riley, the town council began preparations for a demonstration in the form of a march to London to present a petition to the government.[120] Marches of the unemployed, generally termed "hunger marches", had been taking place since the early 1920s, often under the auspices of the communist-led National Unemployed Workers' Movement. This political dimension had associated such marches in the public mind with far-left propaganda.[121] The Jarrow council determined to organise its march free of political connotations, and with the backing of every section of the town.[120] This did not prevent Hensley Henson, the Bishop of Durham, from denouncing it as "revolutionary mob pressure" and condemning the action of James Gordon, the Bishop of Jarrow, who gave the march his blessing.[122] Even within the Labour Party, Wilkinson found the leadership's attitude lukewarm, fearful of possible association with revolutionary socialism.[123][124]

On 5 October 1936 a selected group of 200 set out from Jarrow Town Hall on the 282-mile march,[122] aiming to reach London by 30 October for the start of the new session of parliament.[125] Wilkinson did not march all the way, but joined whenever her various commitments allowed.[126] At that year's Labour Party conference, held in Edinburgh, she hoped to rouse enthusiasm but instead heard herself condemned for "sending hungry and ill-clad men across the country".[127] This negative attitude was mirrored by some of the local parties on the route of the march; in such areas, Wilkinson recorded with irony, the Conservatives and Liberals saw to the marchers' needs.[128] On 31 October the marchers reached London, but Baldwin refused to see them.[129] On 4 November, Wilkinson presented the town's petition to the House of Commons. Signed by 11,000 citizens of Jarrow, it concluded: "The town cannot be left derelict, and therefore your Petitioners humbly pray that His Majesty's Government and this honourable House should realise the urgent need that work should be provided for the town without further delay."[130] In the brief discussion that followed, Runciman opined that "the unemployment position at Jarrow, while still far from satisfactory, has improved during recent months". In reply, a Labour backbencher commented that "the Government's complacency is regarded throughout the country as an affront to the national conscience".[131]

The marchers returned to Jarrow by train, to find their unemployment benefit reduced because they had been "unavailable for work" had any vacancies arisen.[132][133] The historians Malcolm Pearce and Geoffrey Stewart suggest that the success of the Jarrow march lay in the future; it "helped to shape [post-Second World War] perceptions of the 1930s", and thus paved the way to social reform.[134] According to Vernon, it planted the idea of social justice into the minds of the middle classes. "Ironically and tragically," Vernon says, "it was not peaceful crusading, but the impetus of rearmament which brought industrial activity back to Jarrow".[135] Wilkinson published an account of Jarrow's travails in her final book, The Town that was Murdered (1939). "Jarrow's plight", she wrote, "is not a local problem. It is the symptom of a national evil".[136]

International and domestic concerns

[edit]In November 1934, as a representative of the Relief Committee for the Victims of Fascism, Wilkinson visited the northern Spanish province of Asturias to report on the crushing of the Oviedo miners' uprising. She was forcibly ejected from the country.[137][138] Despite being banned from Germany as an undesirable, Wilkinson continued to visit the country covertly, and as a correspondent for the Sunday Referee was the first to report Hitler's intention to march into the Rhineland, in March 1936.[139] Spain, however, came to occupy a special place in her opposition to the spread of fascism. When a section of the Spanish army under General Francisco Franco attacked the elected Popular Front coalition government to precipitate the Spanish Civil War, Wilkinson set up the Spanish Medical Aid Committee and the National Joint Committee for Spanish Relief.[140] She later argued in parliament against the British government's non-intervention policies which, she insisted, "worked on the side of General Franco".[141] She returned to Spain in April 1937 as a member of an all-women delegation led by the Duchess of Atholl, and afterwards wrote of feeling "a helpless, choking rage", as she witnessed the effects of aerial bombing on undefended villages.[142] On a further visit, in December 1937, she was accompanied by Attlee, now leader of the Labour Party, and Philip Noel-Baker, a fellow Labour MP. Having observed the near-starvation of schoolchildren in Madrid, on her return to Britain she set up a "Milk for Spain" fund, together with other humanitarian initiatives.[143]

Although she had long broken her formal ties with the British Communist Party, Wilkinson retained strong links with other communist organisations at home and abroad. Her association with leading communists such as Willi Münzenberg and Otto Katz is revealed in British intelligence files held on her.[144] However, she was not prepared to risk losing her parliamentary seat, and thus kept her rebellious behaviour within bounds.[145][146] In 1937, Wilkinson was one of a group of Labour figures—Aneurin Bevan, Harold Laski and Stafford Cripps were others—who founded the left-wing magazine Tribune; in the first issue she wrote of the need to fight unemployment, poverty, malnutrition and inadequate housing.[147] Mindful of the dependence of many low-income families on credit, she introduced a bill to regulate hire purchase agreements, at the time a subject of frequent abuse, and with all-party support she secured the passage of the Hire Purchase Act 1938.[148]

Wilkinson was a strong opponent of the National Government's appeasement policies towards the European dictators. In the House of Commons on 6 October 1938 she condemned the actions of the prime minister, Neville Chamberlain,[n 11] in signing the Munich Agreement: "Only by throwing away practically everything for which this country cared and stood could he rescue us from the results of his own policy".[150] On 24 August 1939, as parliament considered the recently signed Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Wilkinson attacked Chamberlain's failure to ally with Russia in a common front against Hitler. "Time after time", she told the Commons, "we have had the prime minister ... putting the narrow interests of his class and of the rich, before the national interest".[151]

Second World War

[edit]

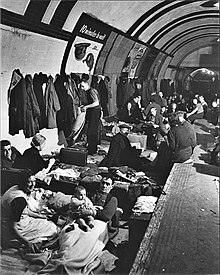

Wilkinson supported Britain's declaration of war on Germany, on 3 September 1939, although she was critical of Chamberlain's conduct of the war.[152] In May 1940, when Churchill's all-party coalition replaced Chamberlain's National Government, Wilkinson was appointed Parliamentary Secretary at the Ministry of Pensions. She transferred to the Ministry of Home Security in October 1940, as one of Herbert Morrison's three Parliamentary Secretaries, with responsibilities for air raid shelters and civil defence.[153] When aerial bombardment of British cities began in the summer of 1940, many Londoners used Underground stations as improvised shelters, often living there for days in conditions of increasing squalor.[154]

By the end of 1941 Wilkinson had supervised the distribution of more than half a million indoor "Morrison shelters"—reinforced steel tables with wire mesh sides, under which a family could sleep at home.[155] Dubbed the "shelter queen" by the press, Wilkinson toured the bombed cities frequently, to share hardships and raise morale.[156] More controversially, she approved the conscription of women into the Auxiliary Fire Service for fire-watching duty, a policy that provoked considerable opposition from women, who felt that their domestic duties were a sufficient burden. Even Wilkinson's own union, NUDAW, disapproved of the measure, but Wilkinson stood firm.[157]

The discipline of working in a ministerial post, together with the influence of Morrison and her alienation from communism, turned Wilkinson away from many of her former left-wing stances. She supported Morrison's decision in January 1941 to suppress the communist newspaper The Daily Worker on the grounds of its anti-British propaganda,[158][159] and voted for the wartime legislation that banned strikes in key industries.[158] Now accepted within the mainstream of the Labour Party, she served on several key policy committees, and in June 1943 became vice-chairman of the party's National Executive. She succeeded to the chair when the incumbent, George Ridley, died in January 1944.[160] In the 1945 New Year Honours she was appointed a Privy Counsellor,[161] only the third woman (after Margaret Bondfield and Lady Astor) to receive this honour.[158][162] In April 1945, she was part of a parliamentary delegation that travelled to San Francisco to begin work on the establishment of the United Nations.[163]

Postwar career

[edit]Leadership manoeuvres

[edit]Wilkinson had formed a close relationship with Morrison, personally and politically, before and during their wartime ministerial association.[3] She thought that he, rather than the sedate Attlee, should be leading the Labour Party, and had promoted his leadership credentials in 1935 and 1939.[164][165] In 1945, Morrison informed Attlee that he intended to seek the leadership "in the interests of party unity".[166] In the general election held in July that year Labour won a landslide victory, with 393 seats against the Conservatives' 213.[167] This did not prevent Wilkinson and others from continuing to press for a change of leader, but Attlee forestalled further action by quickly accepting the King's invitation to form a government. He showed no resentment towards either Morrison or Wilkinson; the former was appointed Lord President of the Council and deputy prime minister, while Wilkinson was made Minister of Education, with a seat in the cabinet. Emmanuel Shinwell, who became Minister of Fuel and Power, later commented that "it is not bad tactics to make one's enemies one's servants".[168][169]

Minister of education

[edit]Wilkinson was the second woman, after Margaret Bondfield, to achieve a place in the British cabinet.[170] As Minister of Education she saw as her main task the implementation of the Education Act 1944 passed by the wartime coalition.[171] This Act provided universal free secondary education, and raised the minimum school leaving age from 14 to 15 with effect from 1947. It said nothing about how secondary education should be organised; Labour's education specialist, James Chuter Ede, who had put the Act through Parliament along with Rab Butler, felt this should be decided at a local authority level. Many experts felt that children should take an examination — the "11-plus" — which would determine whether their secondary education would be in a grammar (academic), technical or "modern" school. However, many in the Labour Party saw this tripartite arrangement as perpetuating elitism, and wanted a scheme based on "multilateral" schools, or what later became known as the "comprehensive" system; Chuter Ede preferred this, but Attlee had felt it necessary to appoint him as Home Secretary, so he had less influence over education.

The system envisaged large schools under a single roof, each with a range of appropriate courses of study for different levels of ability, and flexible movement between courses as children's aptitudes changed.[172][173] Wilkinson believed, however, that such a major reconstruction was unachievable at that time, and limited herself to more attainable reforms.[3] Her cautious attitude disappointed and angered some of the Labour left wing and teachers' representatives, who considered that a great opportunity to incorporate socialist principles into education had been missed.[174] Wilkinson, however, was persuaded to the view that selection at 11 would allow all those with higher IQs, irrespective of class background, to obtain a grammar school education.[175]

Wilkinson made her first priority the raising of the school leaving age. This required the recruitment and training of thousands of extra teachers, and creating classroom space for almost 400,000 extra children.[172] Under the Emergency Training Scheme (ETS), ex-servicemen and women were given grants to train as teachers on an accelerated one-year programme; more than 37,000 had been or were being trained by the end of 1946.[176] The rapid expansion of school premises was achieved by the erection of temporary huts—some of which became long-term features of schools.[172] Wilkinson was determined that the higher leaving age be implemented by 1 April 1947—the date set by the 1944 Act—and in the face of parliamentary scepticism insisted that her plans were on track.[177] Final cabinet approval to honour the April date was given on 16 January 1947.[178]

Other reforms during Wilkinson's tenure as minister included free school milk, improvements in the school meals service, an increase in university scholarships,[172] and an expansion in the provision of part-time adult education through county colleges.[179] In October 1945 she went to Germany to report on how the destroyed German education system could best be reactivated.[180] She was astonished by the speed with which, five months after its defeat, the country's schools and universities were reopening. Other trips included visits to Gibraltar, Malta and Czechoslovakia.[181] In November 1945 she chaired an international conference in London that led to the establishment, a year later, of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).[180] In one of her final speeches in parliament, on 22 November 1946, she emphasised that UNESCO stood for "standards of value ... putting aside the idea that only practical things matter". She prophesied that the organisation "will do great things", and urged the government to give it its full backing.[182]

Illness and death

[edit]Wilkinson suffered for most of her life from bronchial asthma, which she aggravated over the years by heavy smoking and overwork.[183] She had often been ill during the war,[184] and had collapsed during a visit to Prague in 1946.[183] On 25 January 1947 she attended the opening of the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School. The winter of 1946–47 was exceptionally cold, and the ceremony was held out of doors.[185] Shortly afterward, Wilkinson developed pneumonia;[184] on 3 February she was found in her London flat in a coma, and on 6 February 1947 she died in St Mary's Hospital, Paddington.[183]

At the inquest the coroner gave the cause of death as "heart failure following emphysema, with acute bronchitis and bronchial pneumonia, accelerated by barbiturate poisoning".[186] Wilkinson had been taking a combination of drugs for several months, to combat both her asthma and insomnia; the coroner believed she had inadvertently taken an overdose of barbiturates. With no evidence to indicate that the overdose was deliberate, he recorded a verdict of accidental death. Despite this, speculation that Wilkinson had committed suicide has persisted, the reasons cited being the failure of her personal relationship with Herbert Morrison and her likely fate in a rumoured cabinet reshuffle. In their 1973 biography of Morrison, Bernard Donoughue and G. W. Jones suggest that, given Wilkinson's poor health, the burdens of her ministerial office became too much for her. However, the lack of conclusive evidence divides historians about Wilkinson's intention to take her own life.[187][188][189][n 12]

Appraisal and legacy

[edit]Wilkinson's short stature and distinctive red hair, combined with her uncompromising politics, gave rise to popular nicknames such as the "Fiery Particle" and "Red Ellen".[10][191] With her bright, fashionable clothes and her forceful manner, she was easily noticeable—an obituarist wrote that "wherever there was a row going on in support of some good or even fairly good cause, that rebellious redhead was sure to be seen bobbing about in the heart of the tumult".[192] In her later career, ambition and pragmatism led her to temper her earlier Marxism and militancy and work within mainstream Labour Party policy; she came to believe that parliamentary democracy offered a better route to social progress than any alternative.[193] Yet, Vernon says, "she never lost her resolute independence of thought, and sought power not for self glory but to succour the weak of the world".[194]

In a tribute published when Wilkinson's death was announced, the former Conservative MP Thelma Cazalet-Keir summed up her personality: "Ellen Wilkinson was as far removed from being a bore as it is possible for any human being to be. Whatever she did, wherever she went, she created an atmosphere of excitement and interest ... and not just because of her red hair and green dress".[195]

In the course of her career Wilkinson contributed to reforms in numerous policy areas: women's equal suffrage, women civil servants' equal pay, provision of air raid shelters for city dwellers, and protection of hire purchase borrowers' rights.[196] The historian David Kynaston cites as her greatest practical achievement her success in meeting the timetable for the raising of the school leaving age;[197] her successor as education minister, George Tomlinson, recorded how hard she had fought to avoid postponement of the reform, and expressed his sorrow that she died before the set date.[198] Wilkinson was sometimes criticised for extending her efforts too widely; a local newspaper, the North Mail, complained in May 1937 that "Miss Wilkinson is working for too many causes to do justice to Jarrow".[199] Nevertheless, her book The Town that was Murdered brought to public notice the plight of Jarrow and the broader consequences of unbridled capitalism on working-class communities; the book, Harrison observes, "educated the nation".[3]

"Ellen Wilkinson was small in stature, but there were occasions when she dwarfed her colleagues by the tenacity with which she stood up for the principles she held to be right".

Wilkinson never married, although she had numerous close friendships with men. Apart from her early engagement to Walton Newbold, she was close to John Jagger for many years,[201] and in the early 1930s enjoyed a brief romantic attachment with Frank Horrabin.[3] Her long association with Morrison began in her early Fabian days; Morrison was very reticent about this friendship, choosing not to mention Wilkinson in his 1960 autobiography despite their close political association. Vernon says that the relationship almost certainly became "more than platonic", but as Wilkinson's private papers were destroyed after her death, and Morrison maintained silence over the matter, the full nature and extent of their friendship remains uncertain.[188][202] Labour MP Rachel Reeves noted differing opinions among their respective biographers, but cited a recollection by wartime Minister P. J. Grigg as suggesting a friendship that was more than platonic.[203]

On 25 January 1941 Wilkinson received the freedom of the town of Jarrow,[135] and in May 1946 was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Manchester.[22] Her name has been commemorated in The Ellen Wilkinson School for Girls in Ealing, west London,[204] in the Ellen Wilkinson Primary School and Children's Centre in Newham, east London,[205] and in the Ellen Wilkinson Estate, a 1950s Felling Urban District Council housing project at Wardley, once part of her Jarrow constituency, now in Gateshead Metropolitan Borough. In addition, the Ellen Wilkinson High School in Ardwick, which incorporated Wilkinson's old school, bore her name for some years before its closure in 2000.[1][206] The Ellen Wilkinson Building in the University of Manchester's campus houses parts of the Manchester Institute of Education and other departments.[207] A blue plaque records the site of Wilkinson's birthplace at 41 Coral Street,[208] and another, in the main quadrangle of the old university buildings, records Wilkinson's attendance there from 1910 to 1913.[209] In October 2015 Wilkinson was shortlisted by a Manchester town hall panel as one of six candidates to be the subject of the city's first female statue in over a century.[210] In October 2016, Wilkinson was chosen in a public vote to become the first female statue in Middlesbrough.[211] Her name and image and those of 58 other women's suffrage supporters are etched on the plinth of the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London that was unveiled in April 2018.[212]

Ellen Wilkinson was shortlisted in 2015 for the WoManchester Statue, although Emmeline Pankhurst was decisively selected. The book First in the Fight dedicates a chapter to Ellen Wilkinson along with the other nineteen women considered for the statue.[213]

In 2024 Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves, who had said that all art in No 11 would be by female artists or of female subjects, replaced a portrait of former chancellor Nigel Lawson in her office by one of Wilkinson.[214]

Books by Ellen Wilkinson

[edit]- A Workers' History of the Great Strike. London: Plebs League. 1927. OCLC 1300135. Co-authored with Frank Horrabin and Raymond Postgate.

- Clash (Novel). London: George G. Harrap. 1929. OCLC 867888837.

- Peeps at Politicians. London: P. Allen. 1931. OCLC 565308651.

- The Division Bell Mystery. London: George G. Harrap. 1932. OCLC 504369261.

- The Terror in Germany. London: British Committee for the Relief of Victims of German Fascism. 1933. OCLC 35834826.

- Why Fascism?. London: Selwyn and Blount. 1934. OCLC 249889269. Co-authored with Edward Conze

- Why War?: a handbook for those who will take part in the Second World War. London: N.C.L.C. 1935. OCLC 231870528. Co-authored with Edward Conze

- The Town That Was Murdered. London: Victor Gollancz. 1939. OCLC 1423543.

- Plan for Peace: How the People can win the Peace. London: Labour Party. 1945.

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The building housed, successively, Ardwick Higher Grade School, 1894–1911, Ardwick Central School, 1911–52, Ardwick Secondary Technical School, 1952–57, Ardwick Technical School, 1957–67, Nicholls-Ardwick High School (later Ellen Wilkinson High School), 1967 until its closure.[1]

- ^ In June 1914, 12 months after her graduation, Wilkinson's degree was upgraded to MA. In accordance with the university's regulations at that time, no thesis or further study was required.[22]

- ^ Ireland had been in a state of formal rebellion against the British government since December 1918, when the majority of Irish MPs boycotted the Westminster parliament and convened as Dáil Éireann in Dublin. After January 1919 the rebellion escalated into a prolonged armed struggle.[46]

- ^ In the 1923 general election, three Labour women—Margaret Bondfield, Susan Lawrence and Dorothy Jewson—had been elected, but all three lost their seats in 1924.[68]

- ^ The Conservative total included three women, and the Liberals, one. A further woman was elected as an Independent.[89]

- ^ The House of Commons official website explains the role of Parliamentary Private Secretaries thus: "He or she is selected from backbench MPs as the 'eyes and ears' of the minister in the House of Commons. It is an unpaid job but it is useful for an MP to become a PPS to gain experience of working in government."[92]

- ^ Mosley left the Labour Party in February 1931 to form the New Party. Thereafter he moved steadily to the right; in 1932 dissolved the New Party and founded the British Union of Fascists.[96]

- ^ Before 1911 the House of Lords had a power of veto over Commons legislation. Under the Parliament Act 1911 this power was reduced; the Lords could delay legislation other than finance bills for a period of two years. The period of delay was reduced to one year in 1949.[101]

- ^ Wilkinson records that at the end of the meeting MacDonald said to her: "Ellen, why don't you go out and preach socialism, which is the only remedy for all this?" This "priceless remark", she says, brought home the "reality and sham ... of that warm but so easy sympathy".[111]

- ^ The four "special areas" covered by the Act were Scotland, South Wales, West Cumberland and Tyneside. Initially the amount provided for relief for all four areas was £2 million. The historian A. J. P. Taylor comments that "the old industries could not be pulled back to life by a little judicious prodding."[112]

- ^ Baldwin retired as prime minister in May 1937, and Chamberlain succeeded him.[149]

- ^ Chris Wrigley, in his biography of the historian A. J. P. Taylor, claims that Taylor had knowledge of Wilkinson's suicide from the socialist cartoonist and writer Frank Horrabin.[190]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Ardwick Schools Collection". Archivehub. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ Bartley, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Harrison, Brian (2004). "Wilkinson, Ellen Cicely". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36902. Retrieved 3 October 2014. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Wilkinson 1938, p. 402.

- ^ Bartley, p. 2.

- ^ a b Vernon, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Wilkinson 1938, p. 407.

- ^ Wilkinson 1938, p. 403.

- ^ Vernon, p. 6.

- ^ a b Jackson, p. 19.

- ^ a b Bartley, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Wilkinson 1938, p. 405.

- ^ Vernon, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Wilkinson 1938, p. 408.

- ^ Jackson, p. 24.

- ^ Letter from Wilkinson to Middleton, quoted by Bartley, p. 5.

- ^ Vernon, p. 23.

- ^ a b Debenham, pp. 221–24.

- ^ Mitchell, p. 193.

- ^ Vernon, p. 9.

- ^ Vernon, p. 40.

- ^ a b c d Vernon, pp. 28–30.

- ^ Vernon, pp. 33–37.

- ^ Cole 1938, p. 67.

- ^ Jackson. p. 239.

- ^ Bartley, p. 6.

- ^ Cochrane, Kira (11 July 2013). "Join the great suffrage pilgrimage". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Bartley, p. 7.

- ^ Bartley, pp. 8–9.

- ^ "Women's International League". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Vernon, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Bartley, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Perry, pp. 120–125.

- ^ Perry, p. 104.

- ^ Perry, pp. 128–130.

- ^ Bartley, p. 13.

- ^ Vernon, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Bartley, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Bartley, p. 10.

- ^ Vernon, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Perry, pp. 21–23.

- ^ a b Bartley, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Perry, pp. 157–159.

- ^ Vernon, p. 43.

- ^ Leeson, pp. 88 and 179.

- ^ Taylor, pp. 204–06.

- ^ Cole 1949, p. 86.

- ^ a b Bartley, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Cole 1949, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d e Bartley, pp. 23–25.

- ^ a b Vernon, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Perry, pp. 74–77.

- ^ Bartley, p. 18.

- ^ "Communism in Manchester". The Manchester Guardian. 6 November 1922. p. 11. ProQuest 476668095. (subscription required)

- ^ Perry, pp. 32–35.

- ^ Vernon, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Bidwell, Syd (Spring 1953). "National Council of Labour Colleges". International Socialism (12): 25. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Mitchell, p. 206.

- ^ "News report". Ashton-Under-Lyne Reporter. 1 December 1923. p. 5.

- ^ a b c d Vernon, pp. 240–41.

- ^ Blythe, p. 278.

- ^ Vernon, p. 64.

- ^ Bartley, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Marquand, p. 377.

- ^ Andrew, Christopher (September 1977). "The British Secret Service and Anglo-Soviet Relations in the 1920s Part I: From the Trade Negotiations to the Zinoviev Letter". The Historical Journal. 20 (3): 673–706. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00011298. S2CID 159956272. (subscription required)

- ^ Marquand, pp. 381–86.

- ^ a b c d Vernon, p. 242.

- ^ Abrams, p. 229.

- ^ Bartley, p. 28.

- ^ Vernon, pp. 78–79.

- ^ "Civil Estimates And Estimates for Revenue Departments, 1928". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Hansard Online. 1 March 1928. pp. col. 734–35. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Women's Leader, 7 November 1924, quoted in Vernon, p. 78.

- ^ Reeves, Rachel, 1979- (7 March 2019). Women of Westminster : the MPs who changed politics. London. ISBN 978-1-78831-677-4. OCLC 1084655208.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Bartley, pp. 35–36.

- ^ "Training Centres for Women". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Hansard Online. 10 March 1926. pp. col. 2278–79. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "A comprehensive timeline of the EAW branches' establishment and growth in the UK, 1925-29". IET Archives blog. 15 March 2024. Retrieved 8 July 2024.

- ^ Shepherd, p. 237.

- ^ Vernon, p. 88.

- ^ Bartley, p. 42.

- ^ Perry, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Bartley, p. 83.

- ^ Bartley, p. 45.

- ^ Webb, p. 133.

- ^ Perry, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Bartley, p. the 34.

- ^ "Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Hansard Online. 29 March 1928. pp. col. 1402–06. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ a b Bartley, p. 47.

- ^ Marquand, pp. 477–79.

- ^ "Women in Parliament and Government". United Kingdom Parliament. 18 July 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2016. (details in Table 2, p. 6 of 18-page report)

- ^ Bartley, p. 48.

- ^ Vernon, p. 102.

- ^ "Parliamentary Private Secretary". United Kingdom Parliament. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ Bartley, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Skidelsky, pp. 195–209.

- ^ Vernon, pp. 108–09.

- ^ Taylor, pp. 359 and 462.

- ^ Article in The New Dawn, 2 August 1930, quoted in Bartley, p. 53.

- ^ a b Bartley, p. 49.

- ^ "Shop (Hours of Employment) Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Hansard Online. 21 March 1930. pp. col. 2337–38. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Bartley, pp. 52–53.

- ^ "The Parliament Acts". United Kingdom Parliament. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ Marquand, p. 609.

- ^ Blythe, pp. 282–83.

- ^ a b Bartley, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Quoted in Vernon, p. 133.

- ^ Vernon, p. 107.

- ^ Vernon, p. 158.

- ^ Perry, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Vernon, p. 138.

- ^ a b Bartley, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Wilkinson 1939, pp. 195–96.

- ^ Taylor, p. 436.

- ^ Wilkinson 1939, p. 200.

- ^ Wilkinson 1939, pp. 172–73.

- ^ Wilkinson 1939, pp. 175 and 184–85.

- ^ "Iron and Steel Works, Jarrow". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Hansard Online. 30 June 1936. pp. col. 205–07. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Wilkinson 1939, pp. 184–85.

- ^ Vernon, p. 141.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 1939, p. 198.

- ^ a b Vernon, p. 142.

- ^ Bartley, p. 88.

- ^ a b Bartley, p. 89.

- ^ Bartley, p. 91.

- ^ Vernon, p. 143.

- ^ Blythe, p. 191.

- ^ Bartley, p. 90.

- ^ Wilkinson 1939, p. 204.

- ^ Wilkinson 1939, pp. 205–06.

- ^ Bartley, p. 92.

- ^ "Petitions, Jarrow". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Hansard Online. 4 November 1936. pp. col. 75. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Jarrow". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Hansard Online. 4 November 1936. pp. col. 76–77. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Bartley, p. 93.

- ^ Blythe, p. 199.

- ^ Pearce and Stewart, p. 359.

- ^ a b Vernon, pp. 146–47.

- ^ Wilkinson 1939, p. 283.

- ^ Bartley, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Perry, pp. 251–298.

- ^ Bartley, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Bartley, pp. 76–77.

- ^ "Spain". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Hansard Online. 6 May 1937. pp. col. 1359–60. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Jackson, p. 143.

- ^ Bartley, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Perry, pp. 256–265.

- ^ Bartley, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Collette, Christine (3 March 2011). "The Jarrow March". BBC History. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ Vernon, p. 171.

- ^ Gardiner, pp. 531 and 682.

- ^ Taylor, pp. 496–97.

- ^ "Policy of His Majesty's Government". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Hansard Online. 6 October 1938. pp. col. 524–25. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "International Situation". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Hansard Online. 24 August 1939. pp. col. 50–55. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Bartley, p. 102.

- ^ Vernon, pp. 184–85.

- ^ Vernon, pp. 185–86.

- ^ Vernon, p. 188.

- ^ Bartley, pp. 106–08.

- ^ Bartley, pp. 110–11.

- ^ a b c Bartley, pp. 112–13.

- ^ "Suppression of Daily Worker Approved by 297 to 11". The Manchester Guardian. 29 January 1941. p. 2. ProQuest 484965756.(subscription required)

- ^ Vernon, p. 195.

- ^ "No. 36866". The London Gazette (Supplement). 29 December 1944. p. 1.

- ^ Vernon, p. 194.

- ^ Bartley, p. 116.

- ^ Bartley, p. 118.

- ^ Perry, pp. 229–230, 237, 367.

- ^ Jago, p. 163.

- ^ Bartley, p. 119.

- ^ Vernon, pp. 196–98.

- ^ Bartley, p. 121.

- ^ Cracknell, Richard; Keen, Richard (17 July 2014). Women in Parliament and Government. House of Commons Library. p. 7.

- ^ Bartley, pp. 123–24.

- ^ a b c d Bartley, pp. 125–26.

- ^ Vernon, p. 203.

- ^ Rubinstein, David (Spring 1979). "Ellen Wilkinson Re-Considered". History Workshop. 7 (7): 161–69. doi:10.1093/hwj/7.1.161. JSTOR 4288230.(subscription required)

- ^ Perry, pp. 376–378.

- ^ Vernon, pp. 207–08.

- ^ "School-leaving Age (Huts)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Hansard Online. 31 October 1946. pp. col. 758. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Vernon, p. 210.

- ^ Vernon, pp. 215–16.

- ^ a b Bartley, pp. 128–30.

- ^ Vernon, pp. 211–12.

- ^ "United Nations Educational Organisation". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Hansard Online. 22 November 1946. pp. col. 1219–31. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Vernon, pp. 231–33.

- ^ a b Bartley, p. 131.

- ^ Vernon, p. 233

- ^ "Inquest verdict on Miss Wilkinson". The Manchester Guardian. 1 March 1947. p. 3. ProQuest 478719576.(subscription required)

- ^ Vernon, pp. 234–35.

- ^ a b Bartley, pp. 132–33.

- ^ Perry, pp. 384–390.

- ^ Wrigley, p. 116.

- ^ Bartley, p. xi.

- ^ Ian McKay, quoted in Bartley, p. 134.

- ^ Bartley, p. 138.

- ^ Vernon, p. 236.

- ^ Cazalet-Keir, Thelma (9 February 1947). "Miss Ellen Wilkinson: The Tributes of Three Women". The Observer. p. 7. ProQuest 475064921. (subscription required)

- ^ Bartley, pp. 134–35.

- ^ Kynaston, p. 575.

- ^ George Tomlinson, quoted in Hughes, H.D. "Billy" (Spring 1979). "In Defence of Ellen Wilkinson". History Workshop. 7 (7): 157–60. doi:10.1093/hwj/7.1.157. JSTOR 4288229. (subscription required)

- ^ North Mail, 29 May 1937, quoted in Vernon, p. 148.

- ^ Markham, Violet (9 February 1947). "Miss Ellen Wilkinson: The Tributes of Three Women". The Observer. p. 7. ProQuest 475064921.(subscription required)

- ^ Vernon, pp. 124–25.

- ^ Vernon, pp. 126–29.

- ^ Rachel Reeves (2020) Women of Westminster

- ^ "The Ellen Wilkinson School for Girls: A Specialist College for Science and Mathematics". The Ellen Wilkinson School. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ "Ellen Wilkinson Primary School and Children's Centre". Ellen Wilkinson Primary School and Children's Centre. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ "Establishment: Ellen Wilkinson High School". Edubase (UK government). Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ "Ellen Wilkinson Building". University of Manchester. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ "Ellen Wilkinson (1891–1947) Stateswoman and Cabinet Minister, was born at 41 Coral Street on this site". Open Plaques. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ "Ellen Wilkinson (1891–1947) Labour politician and first female Minister of Education graduate BA History 1913, MA 1914". Open Plaques. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ Williams, Jennifer (20 October 2015). "Shortlist of six iconic women revealed for Manchester's first female statue for 100 years". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ "The Eighth Plinth". The Eighth Plinth. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ "Millicent Fawcett statue unveiling: the women and men whose names will be on the plinth". iNews. 24 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ Helen Antrobus and Andrew Simcock, published 2019 ISBN 978-1-84547-252-8)

- ^ Bakare, Lanre (30 October 2024). "Rachel Reeves swaps Nigel Lawson portrait for one of Labour MP 'Red Ellen'". The Guardian.

Sources

[edit]- Abrams, Fran (2003). Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes. London: Profile Books. ISBN 1-86197-425-6.

- Bartley, Paula (2014). Ellen Wilkinson: From Red Suffragist to Government Minister. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-3237-6.

- Blythe, Ronald (1964). The Age of Illusion. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. OCLC 493484388.

- Cole, Margaret, ed. (1938). The Road to Success. London: Methuen. OCLC 504641202.

- Cole, Margaret (1949). Growing Up into Revolution. London: Longmans Green. OCLC 626722.

- Debenham, Claire (2013). Birth Control and the Rights of Women: Post-suffrage Feminism in the Early 20th Century. New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78076-435-1.

- Gardiner, Juliet (2010). The Thirties: An Intimate History. London: Harper Press. ISBN 978-0-00-731453-9.

- Jackson, Angela (2002). British Women and the Spanish Civil War. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-27797-3.

- Jago, Michael (2014). Clement Attlee: The Inevitable Prime Minister. London: Biteback. ISBN 978-1-84954-683-6.

- Kynaston, David (2007). Austerity Britain 1945–51. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-9923-4.

- Leeson, D.M. (2011). The Black and Tans: British Police and Auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-959899-1.

- Marquand, David (1977). Ramsay MacDonald. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-01295-9.

- Mitchell, Hannah (1977). The Hard Way Up. London: Virago. ISBN 0-86068-002-9.

- Pearce, Malcolm; Stewart, Geoffrey (1992). British Political History, 1867–1991. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-07247-6.

- Perry, Matt (2014). Red Ellen Wilkinson: Her Ideas, Movements and World. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-8720-2.

- Shepherd, John (2002). George Lansbury: At the Heart of Old Labour. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820164-8.

- Skidelsky, Robert (1970). Politicians and the Slump: The Labour Government of 1929–31. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-021172-6.

- Taylor, A. J. P. (1970). English History 1914–45. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-021181-0.

- Vernon, Betty D. (1982). Ellen Wilkinson 1891–1947. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-7099-2603-0.

- Webb, Beatrice (1956). Diaries 1924–1932 (edited by Margaret Cole). London: Longmans Green. OCLC 3891268.

- Wilkinson, Ellen (1938). Myself When Young: by famous women of to-day (ed. Margot Countess of Oxford and Asquith). London: F. Muller. OCLC 2155807.

- Wilkinson, Ellen (1939). The Town that was Murdered. London: Victor Gollancz.

- Wrigley, Chris (2006). A.J.P. Taylor : radical historian of Europe. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-286-9.

External links

[edit]- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Ellen Wilkinson

- Ellen Wilkinson profile at Marxists Internet Archive

- Cowan, Steven; McCulloch, Gary; Woodin, Tom (May 2012). "From HORSA huts to ROSLA blocks: the school leaving age and the school building programme in England, 1943–1972" (PDF). History of Education. 41 (3): 361–80. doi:10.1080/0046760X.2011.585143. S2CID 143633951. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- The Labour History Archive and Study Centre at the People's History Museum in Manchester has material in their collection relating to Wilkinson, such as press cuttings and letters.

- Works by Ellen Wilkinson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Newspaper clippings about Ellen Wilkinson in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1891 births

- 1947 deaths

- 20th-century British women politicians

- Alumni of the University of Manchester

- Barbiturates-related deaths

- British Secretaries of State for Education

- British suffragists

- Chairs of the Labour Party (UK)

- Communist Party of Great Britain members

- Deaths from bronchitis

- Deaths from congestive heart failure

- Deaths from emphysema

- Deaths from pneumonia in England

- Drug-related deaths in England

- English Methodists

- English anti-fascists

- English socialists

- English women novelists

- Female members of the Cabinet of the United Kingdom

- Female members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies

- Labour Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies

- Members of the Fabian Society

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- Ministers in the Attlee governments, 1945–1951

- Ministers in the Churchill wartime government, 1940–1945

- National Union of Distributive and Allied Workers-sponsored MPs

- People from Chorlton-on-Medlock

- People from Middlesbrough

- Trade unionists from Manchester

- UK MPs 1924–1929

- UK MPs 1929–1931

- UK MPs 1935–1945

- UK MPs 1945–1950