Ellemann-Jensen doctrine

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2024) |

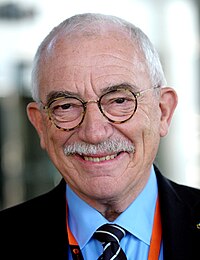

The Ellemann-Jensen doctrine is a set of principles in international relations[1] aimed at increasing the global influence of smaller nations. The doctrine is not a written document but rather an approach inspired by the 1982–1993 tenure of Danish former Foreign Minister Uffe Ellemann-Jensen. He promoted the idea that a small country can gain influence by supporting larger ones that share its values and ideals.

The Ellemann-Jensen doctrine is thus, that a small country – like Denmark – can affect world politics through successfully building alliances to promote its foreign policy goals. An unstated implication of this is that a small country should therefore also be willing to adopt and support the goals of its allies in return.

Historical context

[edit]Danish isolationism

[edit]In the context of Danish political history, the doctrine can be seen as the official break with the isolationist "Spirit of 1864" international policy outlook. In 1864, Denmark lost Second war of Schleswig the last in a series of military defeats resulting in a loss of three quarters of its territory. The "Spirit of '64" can be summed up in the slogan, "what was lost outwards must be won inwards"; Danish policy became a high level of deference towards neighbouring nations and an emphasis on domestic development. Denmark did thus not join any of the European alliances at that time and sought to remain uninvolved in emerging conflicts. Military investments were seldom and primarily defensive. The idea driving these policies was that a country as small as Denmark would be unable to affect the rest of the world.

Following World War I, where Denmark had remained neutral, it was offered larger tracts of German territory by France and the allies. However, unlike the eastern neighbours,[clarification needed] it opted for a settlement by plebiscite including rights for the Germans in Denmark and vice versa. It proved partly successful as the Danish-German border remained one of the few borders which a resurgent Germany did not contest. When Denmark was invaded in World War II, the "Spirit of '64" was seen this time in the form of a swift Danish surrender and a subsequent policy of collaboration. Since Denmark stood no chance of defeating the German invaders alone, it was useless to fight. The policy saved Danish lives but allowed Germany to occupy the country with minimal troops, freeing up troops for the assault on France. Denmark's response stands in stark contrast to the heavy opposition to German invasion given by Norway, for instance.

NATO membership

[edit]The first cracks in the isolationist policy occurred after WWII, when Denmark – fearful of the then Soviet occupation of its Baltic islands – joined NATO. This was further expanded during the so-called "footnote policies" of the 1980s, where the Danish Social Democrats sought a political weakening of the NATO alliance, much like France, through a tactic of inserting footnotes containing reservations or objections into every NATO document that Denmark agreed upon.

Ellemann-Jensen's foreign policy

[edit]The true re-entry of Denmark unto the world political scene occurred under the foreign ministry of Uffe Ellemann-Jensen, during which Denmark made a number of bold international moves. Notably, Denmark led the European recognition of the restored independence of the Baltic States in 1991 when it became the first to re-establish diplomatic relations.[specify] Lesser known is his dispatchment of a small number of military advisors to the Baltic nations, a move that was quickly joined by other Nordic nations, eventually forming a successful lobbying campaign within the Western world for a quick recognition of the Baltic states.

After Ellemann-Jensen

[edit]Under the following government led by the Danish Social Democrats the Ellemann-Jensen doctrine was carried on, and Denmark did not only dispatch peacekeepers to the Balkans in the 1990s, but also had no qualms about committing them to fight if need be. Denmark also became more vocal in the United Nations, launching – for instance – resolutions against human rights abuses in China.

Former prime minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen, who succeeded Uffe Ellemann-Jensen as leader of the Liberal party, deployed Danish troops in the 2003 Iraq war, arguing it was indeed a battle between good and evil. Rasmussen also became the first Danish prime minister to officially denounce the Danish collaboration policy during the Second World War.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ Rasmus Brun Pedersen. "Business as usual? Assessing change and continuity in states foreign policy traditions" (PDF). dpsa.dk. Danish Political Science Association. Retrieved 8 July 2024.

- ^ "Denmark Apologizes for Aiding Nazis". Deutsche Welle. 8 Jul 2024. Retrieved 5 June 2021.