Lizbeth B. Humphrey

Elizabeth B. Humphrey | |

|---|---|

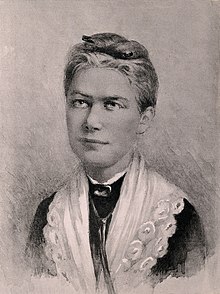

Drawing of Humphrey by Mary J. Jacques | |

| Born | 1841 Hopedale, Massachusetts |

| Died | April 3, 1889 Hamilton, Bermuda |

Elizabeth Bullock Humphrey (May 13, 1841–April 1889), also credited as Lizbeth, Lizzie, or L. B. Humphrey, was an American illustrator active in the 19th century. Humphrey and other women from Cooper Union are considered some of the first women to receive recognition as illustrators in the United States.[1]

After attending Cooper Union, Humphrey illustrated for various magazines and books, including both children's and general magazines.[2] She designed greeting cards, gift books, and other paper goods for publishers L. Prang and Company—where she was a staff illustrator—and Lee and Shepard. After her death, Prang published a memorial book of her artwork.

Early life and work

[edit]Humphrey was born on May 13, 1841, in Millbury[3] or Hopedale, Massachusetts.[4][2] Her mother was Almira B. Humphrey and her father was William H. Humphrey.[5] Her ancestors were a part of the early settlers of Barrington, Rhode Island.[3] She had an adopted sister named Marjorie.[6] In 1849, her family moved to Hopedale, Massachusetts, where Humphrey continued to live for the majority of her life.[3]

In the 1860s, Humphrey studied drawing and painting at Cooper Union in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She used the newly developed technique of photogravure in her artwork, building her illustration style off of it. According to the book Art Work: Women Artists and Democracy in Mid-Nineteenth-Century New York, she "became a trendsetter for the publishing industry" due to her use of the technique.[2] Along with several other Cooper Union students from the 1870s, Humphrey became one of the first women to "achieve recognition" as an illustrator in the United States.[1]

Career

[edit]In 1869, four of her illustrations were included in the book Beyond the Mississippi by Albert D. Richardson, including drawings of Colorado, Nebraska, Texas, and Utah.[4][7]

In the 1870s and onward, Humphrey made accompanying illustrations for various magazines and books.[2] Her illustrations were included in the children's magazines Wide Awake, Oliver Optic's Magazine,[8][9] and St. Nicholas.[10] She illustrated the frontispiece of the book Sally Williams, the Mountain Girl (c. 1872).[2] Her illustrations for the book Wild Flowers and Where They Grow were first printed in Wide Awake magazine, before being reprinted in book form around 1882.[11] According to the Chicago Tribune in 1885, Humphrey was "well known by the excellence of her magazine illustrations".[12]

In the 1880s, Humphrey worked as an illustrator on the staff of L. Prang and Company (L. Prang & Co.). While working for the company, her art was published as chromolithograph prints in gift books and greeting cards.[13][2] She also created holiday cards for Prang, including Christmas,[14] Easter,[15] and Valentine's Day cards.[16] She created a folding calendar for the publisher in 1887, titled "The Meeting of the Months".[17] In the 1880s, Prang also published an American literature series of high-end cards based on designs by Humphrey.[18]

Humphrey also illustrated for the publisher Lee and Shepard, creating works for their series of holiday poems[14] as well as their books. In 1880, they published New Songs for Little People with woodcut illustrations by Humphrey, and Mrs. Follen's Little Songs, designed in the same style.[19] Around 1883, they printed her illustrations in the book Abide With Me.[20] Around 1888, they published a series of "petite" books, which included two books illustrated by Humphrey: Oh, Why Should the Spirit of Mortal be Proud? and The Breaking Waves Dash High.[21]

She also made books for the publisher D. Lothrop & Co.; around 1881, the gift book The Old Oaken Bucket was published by the company. It included illustrations by Humphrey along with a musical ballad.[22] Around 1883, they published The Poet and the Children, a collection of poetry that included illustrations by Humphrey and others.[23]

In 1884, she published Sweet Girl Goldie: A Wonder Story of Butterfly Time, a butterfly-shaped children's book about a little girl named Goldie who frees her uncle's butterfly collection.[24] Also around 1884, Humphrey moved to Boston, Massachusetts.[3] In 1885, one of her illustrated cards was shown in an exhibit of Christmas cards at the Art Institute of Chicago.[12]

Death

[edit]Humphrey died unexpectedly of "consumption" around April 3 or 6, 1889 in Hamilton, Bermuda.[3][25] A week later, her funeral was held in Hopedale, Massachusetts at the Unitarian Church. Representatives from both Lee and Shepard and L. Prang & Co. attended the funeral.[26][25]

After her death that year, L. Prang & Co. announced that the last of her works made for the company would be published during the winter holidays.[27] Prang & Co. also created and published a memorial book of her work, titled Child Life: A Souvenir of Lizbeth B. Humphrey.[2][28] The book contained colored prints of her illustrations, as well as a portrait drawing of Humphrey, sketched by Mary J. Jacques.[29]

Works

[edit]- The Mountain Girl (c. 1872), by Mrs. E. D. Cheney[2][30]

- Abide with Me (1877), by Henry Francis Lyte, engraved by John Andrew & Son[31]

- New Songs for Little People (1880), by Mary E. Anderson

- Little Songs (1880), by Eliza Lee Follen[32]

- Home, Sweet Home (1880), original poetry by John Howard Payne[33]

- The Old Oaken Bucket (c. 1881)[22]

- Wild Flowers and Where They Grow (c. 1882) by Amanda Bartlett Harris[11]

- Merry Thoughts (1882), by M. Jacques[34]

- Ring Out, Wild Bells (1882), by Alfred Tennyson, as part of Lee and Shepard's "Golden Floral" series

- He Giveth His Beloved Sleep (1882), by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, as part of Lee and Shepard's "Golden Floral" series[35]

- The Poet and the Children (c. 1883), compiled by Matthew Henry Lothrop[23]

- Sweet Girl Goldie: A Wonder Story of Butterfly Time (1884)

- Oh, Why Should the Spirit of Mortal be Proud? (c. 1888), by William Knox

- The Breaking Waves Dash High (c. 1888), by Felicia Hemans[21][36]

Gallery of illustrations

[edit]-

"A Pilgrim Daughter", from Amanda Bartlett Harris' book Wild Flowers and Where They Grow

-

Christmas card published by L. Prang and Company

-

Watercolor painting sent in a letter to "Rev. Dr. C.H. Strickland"

-

Chromolithograph print of a study

References

[edit]- ^ a b Rainey, Sue (2007). "Mary Hallock Foote: A Leading Illustrator of the 1870s and 1880s". Winterthur Portfolio. 41 (2/3): 100. doi:10.1086/518924. ISSN 0084-0416. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Masten, April F. (2008). Art Work: Women Artists and Democracy in Mid-Nineteenth-Century New York. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 157, 170–177. ISBN 978-0-8122-4071-9. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Untitled". Fitchburg Sentinel. 10 April 1889. p. 3. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ a b Falk, Peter H. (1998). Record of the Carnegie Institute's International exhibitions, 1896-1996. Sound View Press. p. 1657. ISBN 978-0-932087-55-3. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Vital Records of Milford, Massachusetts, To the Year 1850. p. 95. Retrieved 29 November 2021 – via FamilySearch.

- ^ "Boston Prize card". Louis Prang: Innovator, Collaborator, Educator. American Antiquarian Society. 1882. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Richardson, Albert D. "Beyond the Mississippi". Smithsonian Libraries. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "The April Monthlies". Press and Messenger. 24 March 1875. p. 8. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "Oliver Optic's Magazine". The Evansville Journal. 27 July 1872. p. 2. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "St. Nicholas for June". The Falls City Journal. 1 June 1883. p. 6. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Literary". The Buffalo Commercial. 15 November 1882. p. 1. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ a b "The Art Institute". Chicago Tribune. 11 January 1885. p. 6. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Sivulka, Juliann (2008). Ad Women. Prometheus Books. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-1-59102-672-3. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Recent Deaths". Boston Evening Transcript. 9 April 1889. p. 1. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "Gallery and Studio". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 20 March 1887. p. 2. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "General Art Notes". Chicago Tribune. 24 February 1887. p. 9. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "Specialties". The Publishers' Weekly. Vol. 32, no. 20. 12 November 1887. p. 90. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Marling, Karal Ann (2000). Merry Christmas!: Celebrating America's Greatest Holiday. Harvard University Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-674-00318-7. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "For Christmas and New Year's". Argus and Patriot. 8 December 1880. p. 1. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "An Attractive Book". Carbondale Daily News. 2 February 1883. p. 2. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Other New Books: Lee & Shepard". Times Union. 5 May 1888. p. 7. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ a b "The Holidays". The Pacific Bee. 3 December 1881. p. 6. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ a b "A Triumph for Good Literature". Tunkhannock Republican. 7 December 1883. p. 1. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Evans, Cleveland Kent (21 November 2017). "Evans: Mining for Names and Striking Goldie". omaha.com. Omaha World Herald. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Recent Deaths". Boston Evening Transcript. 11 April 1889. p. 4. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "Deaths". The Boston Globe. 9 April 1889. p. 2. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "Prang's Christmas and New Years Publications". The Publishers' Weekly. Vol. 35, no. 21. 25 May 1889. p. 710. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "Pointers". The Nebraska State Journal. 29 December 1890. p. 5. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "Prang's Art Books and Booklets". Harrisburg Telegraph. 5 December 1890. p. 4. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "Our Book Table". The Chicago Evening Mail. 2 January 1873. p. 2. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "Review of Abide With Me". New England Journal of Education. 6 (21): 250. 1877. ISSN 2578-4145. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "New Books". Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express. 21 December 1880. p. 2. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "New Publications". Detroit Free Press. 18 December 1880. p. 6. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "New Books". The Muscatine Journal. 22 December 1882. p. 1. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "Golden Floral". The Oskaloosa Independent. 25 November 1882. p. 1. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "New Publication". Democrat and Chronicle. 23 November 1887. p. 5. Retrieved 29 November 2021.