Eight O'Clock Walk

| Eight O'Clock Walk | |

|---|---|

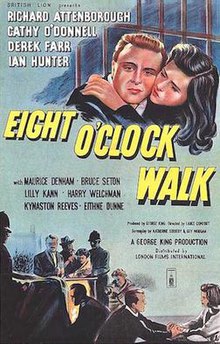

1954 poster for Eight O'Clock Walk | |

| Directed by | Lance Comfort |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | George King |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Brendan J. Stafford |

| Edited by | Francis Bieber |

| Music by | George Melachrino |

Production company | British Aviation Pictures |

| Distributed by | British Lion Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 87 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £49,216[1] |

| Box office | £94,602 (UK)[2] |

Eight O'Clock Walk is a 1954 British drama film directed by Lance Comfort and starring Richard Attenborough, Cathy O'Donnell, Derek Farr and Maurice Denham.[3]

Based on a true story,[4] Eight O'Clock Walk is an anti-capital punishment film (the title refers to the hour at which executions were traditionally carried out) that points out the danger of circumstantial evidence resulting in the death of a mistakenly accused prisoner.[5]

Plot

[edit]Just-married taxi driver Tom Manning is led to an abandoned bombsite by eight-year-old Irene, who says she has lost her doll. She then runs off, taunting Manning as an April-fool prank. He stumbles and raises a fist at her in exasperation, witnessed by local resident Mrs Zunz. Irene is later found murdered on the bomb-site, strangled as she sang "Oranges and Lemons" while feeding the ducks.

Manning is picked up by Scotland Yard for questioning and later arrested and charged with murder, with circumstantial evidence including his handkerchief, a coat fibre and the testimony of Mrs Zunz. A wartime pilot who suffered a head-wound, Manning starts to doubt his mind, wondering if he had suffered a blackout.

Manning's wife, Jill, convinced he is innocent, contacts lawyers, but the defending barrister refuses to see her, wanting to preserve an objective view. She later wins the sympathy of junior counsel Peter Tanner, who visits Manning in prison, believes in his protestation of innocence and makes the case his own.

The trial begins at London's Old Bailey, where Tanner is opposed by his father, prosecuting counsel Geoffrey Tanner. It soon becomes evident that things are going badly for Manning. Jurors are seen expressing their belief in Manning’s guilt even before the trial is over. Irene's mother offers hearsay evidence that Manning had given the victim sweets, and accusing Manning of murder. Following the testimony of prosecution witness Horace Clifford, all the evidence seems to point to Manning's guilt.

During a recess Peter Tanner sees Clifford outside the courthouse, giving a sweet to a young girl. He identifies the sweet as the same as found on Irene. Tanner recalls Clifford for cross-examination, confronting him with the sweets, and instructing a street musician to play "Oranges and Lemons". Clifford breaks down, and Manning is cleared.

Cast

[edit]- Richard Attenborough as Tom Manning

- Cathy O'Donnell as Jill Manning

- Derek Farr as Peter Tanner

- Ian Hunter as Geoffrey Tanner

- Maurice Denham as Horace Clifford

- Bruce Seton as Detective Chief Inspector

- Lily Kann as Mrs. Adeline Zunz

- Harry Welchman as Justice Harrington

- Kynaston Reeves as Munro

- Eithne Dunne as Mrs. Evans

- Cheryl Molineaux as Irene Evans

- Totti Truman Taylor as Miss Ribden-White

- Robert Adair as Albert Pettigrew

- Grace Arnold as Mrs. Higgs

- David Hannaford as Ernie Higgs

- Sally Stephens as Edith Higgs

- Vernon Kelso as Superintendent

- Robert Sydney as Ted Lane, dispatcher

- Max Brimmell as Joe, displaced cabbie

- Humphrey Morton as P.C. Tamplin

- Arthur Hewlett as Reynolds

- Philip King as prison doctor

- Jean St. Clair as Mrs. Gurney

- Enid Hewitt as Grace

- Noel Dyson as gallery regular

- Dorothy Darke as charwoman

- Bartlett Mullins as Hargreaves

- Sue Thackeray as girl

- Ian Fleming as jury member

- Henry B. Longhurst as Clerk of Court

- Elsie Wagstaff as Mrs Peskitt

- Patrick Jordan as prison guard

Production

[edit]The film was shot at Shepperton Studios and on location in London. The film's sets were designed by the art director Norman G. Arnold. It was the final film of the independent producer George King, and was distributed by British Lion.

Reception

[edit]Kinematograph Weekly said: "Human, thoughtful and down-to-earth crime melodrama, pivoting on the Old Bailey. ... Finely acted, shrewdly directed and flawlessly staged, it should intrigue and grip all classes."[6]

Monthly Film Bulletin wrote: "The film's main point of interest is the attempt to build up a convincing picture of the Old Bailey and the legal procedure attending a murder trial. The trial thus possesses a greater degree of authenticity than is usual, but the script clutters up the main story with several unncecessary irrelevances. ... Harry Welchman makes a welcome appearance as the Judge; the rest of the playing is as variable as the script."[7]

Variety said: "Suspense thriller good for local consumption but under-dramatized for U.S. taste. ... The youngsters are all natural, and at times amusing. Lance Comfort keeps to his usual high standard of direction."[8]

In British Sound Films David Quinlan writes: "Promising suspense situation not credibly written, although sturdily acted."[9]

Leslie Halliwell said: "Minor-league courtroom stuff, an adequate time-passer."[10]

References

[edit]- ^ Chapman, J. (2022). The Money Behind the Screen: A History of British Film Finance, 1945-1985. Edinburgh University Press, p. 358

- ^ Porter, Vincent. "The Robert Clark Account", Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, volume 20 no 4, 2000, p. 503

- ^ "Eight O'Clock Walk". British Film Institute Collections Search. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ "EIGHT O'CLOCK WALK - A Timeless Plot". Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ^ Attenborough, Richard; O'Donnell, Cathy; Farr, Derek; Hunter, Ian (10 May 1954), Eight O'Clock Walk, retrieved 27 March 2017

- ^ "Death Goes to School". Kinematograph Weekly. 443 (2391): 2432. 4 February 1954.

- ^ "Death Goes to School". Monthly Film Bulletin. 21 (240): 39. 1 January 1935.

- ^ "Eight O'Clock Walk". Variety (magazine). 194 (13): 6. 24 March 1954.

- ^ Quinlan, David (1984). British Sound Films: The Studio Years 1928–1959. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd. p. 305. ISBN 0-7134-1874-5.

- ^ Halliwell, Leslie (1989). Halliwell's Film Guide (7th ed.). London: Paladin. p. 309. ISBN 0586088946.

External links

[edit]- 1954 films

- 1954 drama films

- Films directed by Lance Comfort

- British drama films

- Films about capital punishment

- Films set in London

- Films shot in London

- British Lion Films films

- Films shot at Shepperton Studios

- Courtroom films

- 1950s English-language films

- British black-and-white films

- 1950s British films

- Films scored by George Melachrino