Old Town, Edinburgh

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

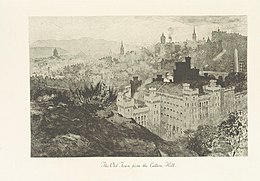

The Old Town seen from Princes Street | |

| Location | Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom |

| Part of | Old and New Towns of Edinburgh |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii)(iv) |

| Reference | 728 |

| Inscription | 1995 (19th Session) |

| Coordinates | 55°56′51.26″N 3°11′29.87″W / 55.9475722°N 3.1916306°W |

The Old Town (Scots: Auld Toun) is the name popularly given to the oldest part of Scotland's capital city of Edinburgh. The area has preserved much of its medieval street plan and many Reformation-era buildings. Together with the 18th/19th-century New Town, and West End, it forms part of a protected UNESCO World Heritage Site.[1]

Royal Mile

[edit]The "Royal Mile" is a name coined in the early 20th century for the main street of the Old Town which runs on a downwards slope from Edinburgh Castle to Holyrood Palace and the ruined Holyrood Abbey. Narrow closes (alleyways), often no more than a few feet wide, lead steeply downhill to both north and south of the main spine which runs west to east.

Significant buildings in the Old Town include St. Giles' Cathedral, the General Assembly Hall of the Church of Scotland, the National Museum of Scotland, the Old College of the University of Edinburgh, Parliament House and the Scottish Parliament Building. The area contains underground vaults and hidden passages that are relics of previous phases of construction.

No part of the street is officially called The Royal Mile in terms of legal addresses. The actual street names (running west to east) are Castlehill, Lawnmarket, High Street, Canongate and Abbey Strand.[2]

Street layout

[edit]The street layout, typical of the old quarters of many northern European cities, is made especially picturesque in Edinburgh, where the castle perches on top of a rocky crag, the remnants of an extinct volcano, and the main street runs down the crest of a ridge from it. This "crag and tail" landform was created during the last ice age when receding glaciers scoured across the land pushing soft soil aside but being split by harder crags of volcanic rock. The hilltop crag was the earliest part of the city to develop, becoming fortified and eventually developing into the current Edinburgh Castle. The rest of the city grew slowly down the tail of land from the Castle Rock. This was an easily defended spot with marshland on the south and a man-made loch, the Nor Loch, on the north. Access to the town was restricted by means of various gates (called ports) in the city walls, of which only fragmentary sections remain.

The original strong linear spine of the Royal Mile only had narrow closes and wynds leading off its sides. These began to be supplemented from the late 18th century with wide new north–south routes, beginning with the North Bridge/South Bridge route, and then George IV Bridge. These rectilinear forms were complemented from the mid-19th century with more serpentine forms, starting with Cockburn Street, laid out by Peddie and Kinnear in 1856, which specifically improved access between the Royal Mile and the newly built Waverley Station.

The Edinburgh City Improvement Act of 1866 further added to the north south routes. This was devised by the architects David Cousin and John Lessels.[3] It had quite radical effects:

- St Mary's Wynd was demolished and replaced by the much wider St Mary's Street with all new buildings.

- Leith Wynd which descended from the High Street to the Low Calton was demolished. Jeffrey Street started from Leith Wynd's junction with the High Street, opposite St Mary's Street, but bent west on arches to join Market Street.

- East Market Street was built to connect Market Street and New Street.

- Blackfriars Street was created by the widening of Blackfriars Wynd, removing all the buildings on the east side.

- Chambers Street was created, replacing N College Street and removing Brown Square (west) and Adam Square (east). It was named after the then Lord Provost of Edinburgh, Sir William Chambers, and his statue placed at its centre.

- Guthrie Street was created, linking the new Chambers Street to the Cowgate.

Sections

[edit]

In addition to the Royal Mile, the Old Town may be divided into various areas, namely from west to east:

- West Port, the old route out of Edinburgh to the west

- Grassmarket, the area to the south-west

- Edinburgh Castle

- The Cowgate, the lower southern section of the town[4]

- Canongate, a name correctly applied to the whole eastern district

- Holyrood, the area containing Holyrood Palace and Holyrood Abbey

- Croft-An-Righ, a group of buildings north-east of Holyrood

Residential buildings

[edit]

Due to the space restrictions imposed by the narrowness of the "tail", and the advantages of living within the defensive wall, the Old Town became home to some of the world's earliest "high rise" residential buildings. Multi-storey dwellings became the norm from the 16th century onwards. Many of these buildings were destroyed in the Great Fire of Edinburgh in 1824; the rebuilding of these on the original foundations led to changes in the ground level and the creation of numerous passages and vaults under the Old Town. The construction of new streets including North Bridge and South Bridge in the 18th century also created underground spaces, such as the Edinburgh Vaults below the latter.

Traditionally buildings were less dense in the eastern, Canongate, section. This area underwent major slum clearance and reconstruction in the 1950s, thereafter becoming an area largely of Council housing. From 1990 to 2010, major new housing schemes appeared throughout the Canongate. These were built to a much higher scale than the older buildings and have greatly increased the population of the area.

Archaeology

[edit]Archaeological work is usually required to be undertaken in advance of development work in the Old Town and this work has shed light on aspects of the Old Town's past. Some recent excavations have been:

- In 2012, AOC Archaeology's excavations in Advocates Close found the remains of a 16th-century tenement and rare 12th/13th century deposits (which were usually removed by later building construction). The artefacts found showed the expansion of the area in 16th and 17th centuries, as well as the decline during the later 17th and early 18th centuries.[5]

- In 2008, Headland Archaeology conducted excavations between the High Street and Jeffrey Street and found evidence of the medieval burgage plots; the construction of multi-storey tenement buildings that characterise much of the Old Town 16th century and their later demolition; as well as a tannery that was established on part of the site by the 1830s and expanded to cover much of the site by the 1880s.[6]

- In 1999 and 2000, archaeologists found part of the medieval boundary ditch under St Mary's Street.[7] Work in the Canongate has also found parts of the boundary ditch,[8] as well as in the Cowgate.[9] In 2015, excavations by AOC Archaeology at East Market Street found the north/ north-east portion of the boundary ditch.[10]

- The excavations at the new Parliament building found over a thousand years of development and changes to the southern tip of the Old Town.[11]

- Excavations, also for the Parliament Building, at Queensberry House found evidence that Charles Maitland, Lord Hatton may have converted the kitchen of Queensberry House into a workshop to illegally skim money from the Royal mint.[11]

- Various excavations since the 1980s have helped to understand St Giles Cathedral[12] and the City Walls.[13]

- Excavations from the 1970s through till the 2000s has shed light on the tenements that existed before the Tron Kirk.[14]

Major events

[edit]

In 1824 a major fire, the Great Fire of Edinburgh, destroyed most of the buildings on the south side of the High Street section between St. Giles Cathedral and the Tron Kirk.

During the Edinburgh International Festival the High Street and Hunter Square become gathering points where performers in the Fringe advertise their shows, often through street performances.

On 7 December 2002, the Cowgate fire destroyed a small but dense group of old buildings on the Cowgate and South Bridge. It destroyed the famous comedy club, The Gilded Balloon, and much of the Informatics Department of the University of Edinburgh, including the comprehensive artificial intelligence library.[15] The site was redeveloped 2013-2014 with a single new building, largely in hotel use.

Old Town Renewal Trust

[edit]In the 1990s the Old Town Renewal Trust in conjunction with the City of Edinburgh developed an action plan for renewal[16][17][18][19]

Redevelopment

[edit]

An area directly to the north of the Canongate has seen a large redevelopment project originally named Caltongate, but since rebranded as New Waverley. The scheme involved building of a mix of residential, hotel, retail and office buildings on the site of the former SMT bus depot in New Street, developing the arches under Jeffrey Street, redeveloping other surrounding sites and creating a pedestrian link from the Royal Mile to Calton Hill.[20] The proposals were criticised by commentators including the author Alexander McCall Smith and Sheila Gilmore MP who regard the modern design as incompatible with the existing older architectural styles of the Old Town and inappropriate for a UNESCO World Heritage site.[21] The Caltongate development was also opposed by the Cockburn Association[22] and the Architectural Heritage Society of Scotland. The site developers Artisan Real Estate Investors have stated that the completed development will be a "vibrant, exciting" place. The plans were approved by the City of Edinburgh Council in January 2014[23] with construction taking place in the late 2010s.

See also

[edit]- Banknotes of Scotland (featured on design)

- History of Edinburgh

- List of Category A listed buildings in the Old Town, Edinburgh

- Scotland in the High Middle Ages

- Timeline of Edinburgh history

- World Heritage Sites in Scotland

References

[edit]- ^ "Edinburgh-World Heritage Site". VisitScotland. Archived from the original on 22 February 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ Marshall, Gary (2015), All about Edinburgh. The Royal Mile, Edinburgh : Castlehill, Lawnmarket, High Street, Canongate, Abbey Strand, Horse Wynd, Edinburgh G.L.G. Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9934903-2-3

- ^ Edinburgh: Mapping the City by Christopher Fleet and Danial MacCannell

- ^ "Edinburgh revamp.(Scotland)(Cowgate site)(Brief Article)", Building Design (1639), UBM Information Ltd: 7(1), 27 August 2004, ISSN 0007-3423

- ^ "Vol 67 (2017): Where There's Muck There's Money: The Excavation of Medieval and Post-Medieval Middens and Associated Tenement at Advocate's Close, Edinburgh | Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports". journals.socantscot.org. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ^ "Vol 58 (2014): Excavations at Jeffrey Street, Edinburgh: the development of closes and tenements north of the Royal Mile during the 16th-18th centuries | Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports". journals.socantscot.org. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "Vol 56 (2013): Excavations in the Canongate Backlands, Edinburgh | Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports". journals.socantscot.org. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "Vol 56 (2013): Excavations in the Canongate Backlands, Edinburgh | Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports". journals.socantscot.org. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "Vol 42 (2011): Through the Cowgatelife in 15th-century Edinburgh as revealed by excavations at St Patrick's Church | Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports". journals.socantscot.org. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "Vol 78 (2018): The Excavation of a Medieval Burgh Ditch at East Market Street, Edinburgh: Around the Town | Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports". journals.socantscot.org. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Vol 40 (2010): Artefactual, environmental and archaeological evidence from the Holyrood Parliament Site excavations | Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports". journals.socantscot.org. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "Vol 22 (2006): Archaeological excavations in St Giles' Cathedral Edinburgh, 1981-93 | Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports". journals.socantscot.org. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "Vol 10 (2004): Conservation and change on Edinburgh's defences:archaeological investigation and building recording of the Flodden Wall, Grassmarket 1998-2001 | Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports". journals.socantscot.org. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "Vol 55 (2013): Marlin's Wynd: new archaeological and documentary research on Post-medieval settlement below the Tron Kirk, Edinburgh. | Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports". journals.socantscot.org. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ at 09:36, Tim Richardson 12 Dec 2002. "Fire guts Edinburgh's AI library". www.theregister.co.uk.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Edinburgh Old Town Renewal Trust; Edinburgh Old Town Trust. Annual report (1992), Edinburgh Old Town Renewal Trust, Edinburgh Old Town Renewal Trust, retrieved 10 October 2016

- ^ Edinburgh Old Town Renewal Trust; Edinburgh (Scotland). Planning Department (1992), Action plan for the Old Town, Edinburgh Old Town Renewal Trust : City of Edinburgh District Council Planning Department, retrieved 10 October 2016

- ^ Edinburgh Old Town Renewal Trust; Edinburgh (Scotland). Planning Department (1993), Action plan for the Old Town : first review, Edinburgh Old Town Renewal Trust : City of Edinburgh District Council Planning Department, retrieved 10 October 2016

- ^ Edinburgh Old Town Renewal Trust; Edinburgh (Scotland). Planning Department (1994), Action plan for the Old Town : second review : April 1994, Edinburgh Old Town Renewal Trust : City of Edinburgh District Council Planning Department, retrieved 10 October 2016

- ^ "Caltongate masterplan". Frameworks, masterplans and design briefs. City of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ "Caltongate development approved by Edinburgh Council". Scotland on Sunday. 29 January 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ "The Caltongate Development". Cockburn Association. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ David McCann (30 January 2014). "Caltongate work to start in summer". Edinburgh Evening News. Retrieved 31 January 2014.