Foodscaping

Foodscaping is a modern term for integrating edible plants into ornamental landscapes. It is also referred to as edible landscaping and has been described as a crossbreed between landscaping and farming.[1] As an ideology, foodscaping aims to show that edible plants are not only consumable but can also be appreciated for their aesthetic qualities. Foodscaping spaces are seen as multi-functional landscapes that are visually attractive and also provide edible returns.[2] Foodscaping is a method of providing fresh food affordably and sustainably.[3]

Differing from conventional vegetable gardening, where fruits and vegetables are typically grown in separate, enclosed areas, foodscaping incorporates edible plants as a major element of a pre-existing landscaping space.[1] This may involve adding edible plantations to an existing ornamental garden or replacing traditional, non-edible plants with food-yielding species.[4] The designs can incorporate various kinds of vegetables, fruit trees, berry bushes, edible flowers, herbs, and purely ornamental species.[5] The design strategy of foodscaping has many benefits, including increasing food security, improving the growth of nutritious food, and promoting sustainable living.[4] Edible landscaping practices may be implemented on both public and private premises.[5] Foodscaping can be practiced by individuals, community groups, businesses, or educational institutions.[6]

Foodscaping is believed to have gained popularity in the 21st century for several reasons. Some accounts claim that the rise of foodscaping is due to the volatility of global food prices and the financial crisis of 2007–2008.[5] However, other accounts suggest that the spike in foodscaping popularity is linked to urbanization and increasing concerns for environmental sustainability.[1]

Origins

[edit]Overview

[edit]

It is unknown who first coined the expression foodscaping. The term and ideology of foodscaping have been around since the late 20th century, yet have only come into popular use during the 21st century. Despite the modernity of foodscaping, integrating edible plants into landscaping spaces is not a new concept. Similar practices date back to ancient and medieval gardening and agricultural techniques.[5] Foodscaping as a contemporary theory presents "a modern take on the way that past generations utilized land".[7] Unlike most historical horticultural practices, foodscaping explicitly supports the idea that edible landscapes can be just as aesthetically pleasing as purely decorative landscapes.[2] Foodscaping advocates attempt to subvert the conventional perception of vegetable gardens as unattractive and instead view edible crops as design features in and of themselves. It is sometimes believed that this ideology emerged from increasingly experimental approaches to gardening and landscaping in the modern era.[5]

Historical precedents of foodscaping

[edit]Edible landscaping techniques practiced in different historical cultures and periods can be seen as ancestors of foodscaping. In Ancient Rome, Roman villa gardens were often both productive and ornamental, though agricultural production was the primary purpose of earlier villa gardens. Archaeological research suggests that these Roman gardens took on various forms such as large vineyard landscapes or small herb gardens. Kitchen gardens, vineyards, and orchard played an important role in the lives of ancient Romans, whose diets were largely based on fruit and vegetables.[8]

In Mesoamerican culture, elaborate gardens and horticultural gardens were a pleasure of Aztec elites. Flowering, fragrant and medicinal plants were believed to be "perquisites of the lords". According to historical letters written by Aztec nobles, impressive gardens often included bright flower beds, fruit trees, herbs, and sweet-smelling flowers. Groves, orchards, and water gardens were sometimes incorporated into the designs of the more elaborate gardens.[9]

Another ancient precedent to foodscaping can be found in Mesopotamia. Babylonians and Assyrians created gardens throughout cities and in palace courtyards that were a representation of Paradise. These featured fragrant trees and edible fruits. Archaeological evidence suggests that, in roughly 1000 BCE, Assyrian Kings developed a naturalistic landscape style in which streams of water ran through gardens that grew plants such as junipers, almonds, dates, rosewood, quince, fir pomegranate, and oak.[10]

During the Renaissance era, villa and chateau gardens in Europe often yielded fruit and vegetables to sell locally. The profits were used to support the villa's or chateau's maintenance costs. Some of the common kinds of plants integrated into the elaborate Renaissance garden designs included figs, pears, apples, strawberries, cabbage, leeks, onions, and peas.[5]

It is believed that village workers created English cottage gardens during Elizabethan times as a personal source of vegetables. Flowers were also planted within these gardens for ornamental purposes.[11]

Recent trends

[edit]Urban growth

[edit]

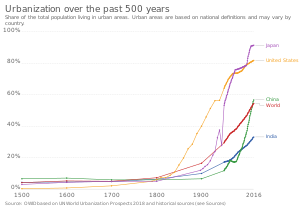

As a result of rapid urbanization seen in recent decades, methods of food production have undergone significant change.[6] According to the United Nations, the Earth's urban population has "grown rapidly from 746 million in 1950 to 3.9 billion in 2014".[12] These accelerated trends in urbanization and population density during the late 20th and 21st century have placed stress on the availability of agricultural land and contributed to growing food insecurity.[6] As a result, there has been an increased desire to re-introduce food growth into urban environments.[5] The ongoing rise in the human population, as well as international goals to reduce hunger and malnutrition, have further escalated the demand for food nutrients.[13] It is believed that these factors have increased the number of people adopting foodscaping strategies.[5]

Sustainability

[edit]Food security

[edit]Foodscaping is widely accepted to increase food security, availability, and accessibility.[14] The instability of supermarket prices can affect food availability. As "self-sufficient food systems", edible landscapes can help decrease a household's dependence on imported food. Foodscaping provides these households with access to a sustainable food source, even when faced with unpredictable circumstances such as the inability to procure food from commercial stores or periods of low financial income.[6]

Depending on the premise's size and scale, significant financial costs can be involved in the initial design and creation of edible landscaping.[15] However, it is still generally accepted that foodscaping can help to lower food costs once the products of the edible plants have been harvested.[2]

In increasing the quantity of locally grown and consumed produce, foodscaping also promotes local food sustainability.[4] It is also believed that foodscaping can help to address the demand for food within the context of global issues such as overpopulation, an unpredictable climate and waning energy resources.[16]

Energy and waste management

[edit]Large-scale agricultural premises typically require large amounts of energy, such as the use of diesel, propane, and electricity to carry out farming operations.[17] The practice of edible landscaping often uses less energy and produces less waste than traditional methods of food production. This is because the food products cultivated from edible landscaping usually involve little processing, packaging or refrigeration.[6]

Foodscaping can also help reduce food miles by decreasing the need for long-distance transportation of food.[4] "A grocery store has on average 1,500 miles per product", says horticulturalists and foodscaping advocate Brie Arthur. These ships and trucks emissions leave a harmful carbon footprint, which could be reduced through the practice of growing edible plants at home instead of buying fresh produce.[18] Foodscaping can further allow participants to help reduce the use of fossil fuel-based pesticides and fertilizers which negatively impact the environment.[6]

Health and nutrition

[edit]A common motivation behind foodscaping is the desire to grow, cook, and consume foods of high nutritious content.[19] In a 2014 research survey conducted by the Australian Institute, 71% of surveyed foodscaping households in Australia were incorporating edibles into their gardens for access to fresh, healthier produce.[20] It is generally accepted that homegrown fruits and vegetables are fresher and more nutritious than supermarket produce, which is sometimes sold multiple days or even weeks after harvesting.[21]

In recent years, increasing concern has been expressed towards the health effects of the chemical additives and preservatives in commercially grown fruit and vegetables.[21] Foodscaping has been considered a way to reduce exposure to chemically modified produce.[22]

Edible landscaping allows participants to increase fresh food production in urban areas. In these areas, the most accessible kinds of food are typically processed kinds, which can lead to greater dietary intakes of sugar, sodium, and fat.[6] Many academic studies have inferred strong links between urban gardening and healthy lifestyle choices. The gardening practices involved in foodscaping are believed to increase participants' fruit and vegetable consumption and the value of preparing nutritious meals.[23]

Research has also demonstrated that creating green spaces (created via methods such as foodscaping) can increase an individual's overall mental health in addition to physiological health benefits. This is achieved through its positive impact on socioeconomic factors such as community attachment, reduced crime, and socialization.[24]

Maintenance

[edit]Input

[edit]Depending on the scale of the edible landscape, foodscaping may require extra time and manual labour to maintain, unlike a regular garden or landscape.[5] This is as the aim of foodscaping is to yield edible returns while also remaining aesthetically pleasing,[2] which may involve added watering, fertilization, pest control and pruning.[5] A lack of time and unsuitable conditions such as climate and insufficient shade can be significant deterrents for people wishing to create edible landscapes.[15] However, maintenance requirements can be reduced by choosing plant species that are suited to the geographic location, climate, and conditions of the area to be foodscaped.[2]

Harvesting

[edit]During certain times of the year, monitoring the ripeness of food production is a requirement for successful foodcaping.[5] If fruits are not harvested at the correct time, they may rot and become visually unappealing within an edible landscape. This may also attract undesired pests or vermin.[2]

Plants

[edit]

Plants in foodscaping designs are typically chosen for their aesthetic and edible appeal.[19] Many vegetables can add colour to foodscaping spaces. Swiss chard, cabbage, and lettuce species come in many colourful varieties, making them a popular choice for foodscaping.[4] Edible flowers, such as carnations, marigolds, cornflowers and pansies can also be used to add decoration and brightness to an edible landscape.[25]

Garden writer Charlie Nardozzi suggests that lemon, apple, plum, and cherry trees can serve as edible alternatives for ornamental trees. He also proposes that blueberry, elderberry and gooseberry plants can substitute popular decorative shrubs such as roses, hydrangeas and privet hedges. Alpine strawberries and chives have also been suggested as suitable replacements for non-edible flowering plants.[26]

Edible landscapes generally consist of a combination of annual and perennial plants.[4] When planning an edible landscape, it is important to know that certain plants require particular environmental conditions.[2] One should also consider the seasonality of the edible plants being used, meaning the time of the year during which a certain species will grow best. Cool season crops require lower temperatures for growth and seed germination, whilst warm season crops are plants that thrive in higher soil and air temperatures.[27] In hot climates, the ideal plants for foodscaping are those that require little water, such as beans, spinach and broccoli. Whilst certain fruit trees, berries and rhubarb are suitable for cooler climates, root vegetables, cabbages and peas are examples of plants that cope well in extremely cold conditions.[28]

-

Beetroot (Beta vulgaris)

-

Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata)

-

Tomato vine (Solanum lycopersicum)

-

Chili peppers (Capsicum annuum)

-

Flowering rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus)

-

Plum (Prunus domestica)

-

Raspberry (Rubus idaeus)

-

Calendula flower (Calendula officinalis)

-

Marigold flower (Tagetes erecta)

-

Camomile flower (Matricaria chamomilla)

-

Cornflower (Centaurea cyanus)

-

Pansy flower (Viola tricolor var. hortensis)

Examples of foodscaping

[edit]People

[edit]Landscape designer and author Rosalind Creasy has frequently been named the "pioneer of edible landscapes" in gardening-related media and publications.[31] Since the 1970s, she has written over twenty books on edible landscaping.[18] One of her most influential works in foodscaping is her book The Complete Book of Edible Landscaping, published in 1982.

Brie Arthur is an American professional horticulturalist who has been noted as a public advocate for the practice of suburban foodscaping.[18] In order to challenge the idea that ornamental landscapes can't involve edible plants, she has spoken publicly at schools, worked with television programs, and been involved in various horticulture-related associations.[32] Her debut book titled The Foodscape Revolution, Finding a Better Way to Make Space for Food and Beauty in Your Garden was published in 2017.

Public projects

[edit]

The Ornamental Kitchen Garden is an edible landscape on the grounds of the château of Villandry, located in the Loire Valley region of France. The Italian Renaissance-style garden is composed of nine square patches, each featuring a geometric design of flowers and vegetables whose design layouts change with each bi-annual planting. These patches are lined with neat box hedges, and each displays vegetables of different colours such red cabbage, beetroot and blue leek. Each year, forty species of vegetables within eight plant families are planted.[33]

Based in Iowa, Backyard Abundance is a non-profit organization founded in 2006 that aims to educate more people about edible landscaping. They encourage community residents to take part in creating transformative landscapes that can help to reduce human impact on the environment.

Founded in Kansas, 2006, Edible Estates is a foodscaping initiative that works with local art institutions and community garden groups in different cities worldwide to create productive edible landscape designs.[34]

Edible Landscapes London is a non-profit organization that creates productive forest gardening spaces that integrate fruiting trees and herbs. They created the first-ever accredited course that trains people in forest gardening practices. According to Lindsay Oberst in an article on Food Revolution Network, Edible Estates "strives to inspire others to look at underused or misappropriated green spaces in a new light, highlighting new contexts for food production and connections to the natural environment".[34]

NYU's Urban Farm Lab is a collaborative urban agriculture project promoting the integration of edible crops into urban environments. They have implemented foodscaping techniques in many spots around the university's campus.[35]

The Eden Project is a sustainability project in Cornwall, England, which attracts over a million yearly visitors.[16] The 15-hectare site features large domes and a food garden, with edible produce incorporated into the landscaping design.[16]

The Food Forest is a property in Adelaide, Australia, which grows 160 varieties of organic fruit, nuts, wheat, and vegetables on 15 hectares of land. The owners educate visitors on how ordinary families can grow their food at home by creating productive foodscapes.[16]

The Netherlands' first "roof field" was created on top of a large office building near Rotterdam's central station in 2012 by Binder Groenprojecten. The 1000m2 "roof field" is used to grow vegetables, fruits, and Herbs, and also houses honeybees.[36]

Wayward is a landscaping, art and architecture firm based in London that combines creative food growing with contemporary art and architecture installations.[34]

See also

[edit]- Allotment garden

- Aquascaping

- Back garden

- Climate-friendly gardening

- Community garden

- Computer-aided garden design

- Flower garden

- Forest gardening

- Garden designer

- Garden buildings

- Index of gardening articles

- Landscape architecture

- List of gardening topics

- Open Gardens

- Naturescaping

- Pizza farm

- Roof garden

- Royal Horticultural Society

- Sustainable landscaping

- Urban horticulture

- Vertical farming

- Victory garden

- Xeriscaping

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Waterford, Douglas. 21st Century Homestead: Urban Agriculture. Lulu, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brown, Sydney P. "Edible Landscaping". The Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, 2016, edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/EP/EP14600.pdf. Accessed 12 April 2020.

- ^ "ENH1330/EP594: Edible Landscaping Using the Nine Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Principles". Ask IFAS - Powered by EDIS. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Arthur, Brie. The Foodscape Revolution: Finding a Better Way to Make Space for Food and Beauty in Your Garden. Pennsylvania, St. Lynn’s Press, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Çelik, Filiz D. "The Importance of Edible Landscape in the Cities". Turkish Journal of Agriculture – Food Science and Technology, vol. 5, no. 2, 2017, pp.118–24, doi:10.24925/turjaf.v5i2.118-124.957 Accessed 19 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Karaca, Elif. "Edible Landscapes as a Solution to Food Security Problem". Theory and Practice in Social Sciences, edited by Viliyan Krystev, et al., St. Kliment Ohridski University Press, 2019, pp. 227–36.

- ^ Arthur, Brie. "Foodscaping: revolution or evolution?". Acta Horticulturae, 1212, 2018, pp. 279–84, admin.ipps.org/uploads/3B-Arthur-Brie-Foodscape.pdf. Accessed 28 March 2020.

- ^ Jashemski, Wilhelmina F., et al., editors. Gardens of the Roman Empire. Cambridge University Press, 2017, doi: doi.org/10.1017/9781139033022. Accessed 18 March 2020.

- ^ Evans, Susan Toby. "Aztec Royal Pleasure Parks: Conspicuous Consumption and Elite Status Rivalry.” Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes, vol. 20, no. 3, Taylor & Francis Group, Sept. 2000, pp. 206–28, doi:10.1080/14601176.2000.10435621 Accessed 1 June 2020.

- ^ Dalley, Stephanie. "Ancient Mesopotamian Gardens and the Identification of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon Resolved." Garden History, vol. 21, no. 1, Garden History Society, July 1993, pp. 1–13, doi:10.2307/1587050 Accessed 1 June 2020.

- ^ Scott-James, Anne. The Cottage Garden. Allen Lane, 1981.

- ^ "World's population increasingly urban with more than half living in urban areas". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 10 July 2014, www.un.org/en/development/desa/news/population/world-urbanization-prospects-2014.html. Accessed 13 April 2020.

- ^ Myers, Melvin L. "Agriculture and Natural Resources Based Industries". Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety, edited by Jeanne M. Stellman, vol. 3, International Labour Office, 1988.

- ^ Stefani, Monique C., et al. (2018). "Toward the Creation of Urban Foodscapes: Case Studies of Successful Urban Agriculture Projects for Income Generation, Food Security, and Social Cohesion". Urban Horticulture: Sustainability for the Future, edited by Dilip Nandwani, Springer, 2018, p. 91.

- ^ a b Conway, Tenley M. "Home-based Edible Gardening: Urban Residents' Motivations and Barriers". Cities and the Environment, vol. 9, no. 1, 2016, article 3, pp. 1–21. Digital Commons, digitalcommons.lmu.edu/cate/vol9/iss1/3/. Accessed 4 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d Tovey, Nina. "Grow food not lawns with the fertile world of foodscaping". Endeavour College of Natural Health, 10 November 2014, www.endeavour.edu.au/about-us/blog/grow-food-not-lawns-with-the-fertile-world-of-foodscaping/. Accessed 16 April 2020.

- ^ Hicks, Susan. "Energy for growing and harvesting crops is a large component of farm operating costs". U.S. Energy Information Administration, 17 October 2014, www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=18431. Accessed 20 April 2020.

- ^ a b c "Gardening: Foodscapes -- where beauty co-exists with bounty". Richmond Times-Dispatch. 10 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ a b Eastman, Janet. "Change out plants for ones you can eat: 'Foodscaping' edible landscape". The Oregonian/Oregon Live, 31 July 2015, www.oregonlive.com/hg/2015/07/edible_landscape_charlie_nardo.html. Accessed 16 Apr.

- ^ Wise, Poppy. "Grow Your Own: The potential value and impacts of residential and community food gardening". The Australian Institute, 31 March 2014, www.tai.org.au/content/grow-your-own. Accessed 13 April 2020.

- ^ a b Spellman, Frank R., & Joan Price-Bayer. Regulating Food Additives: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Rowman & Littlefield, 2019.

- ^ Dolce, Anne. "What is Foodscaping?" The Daily Meal, 5 June 2013, www.thedailymeal.com/foodscaping-fancy-word-gardening-or-important-initiative. Accessed 13 April 2020.

- ^ Garcia, Mariana T., et al. "The impact of urban gardens on adequate and healthy food: a systematic review". Public Health Nutrition, vol. 21, no. 2, Feb. 2018, pp. 416–25, doi:10.1017/S1368980017002944 Accessed 16 April 2020.

- ^ Hall, Charles R.; Knuth, Melinda J. (1 December 2019). "An Update of the Literature Supporting the Well-Being Benefits of Plants: Part 3 - Social Benefits". Journal of Environmental Horticulture. 37 (4): 136–142. doi:10.24266/0738-2898-37.4.136. ISSN 0738-2898.

- ^ "Foodscaping: A "New" Way To Create A Garden". Garden Culture Magazine. 12 January 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Nardozzi, Charlie. Foodscaping: Practical and Innovative Ways to Create an Edible Landscape. Massachusetts, Cool Springs Press, 2015.

- ^ ""Cool" vegetables for you to grow this spring". MSU Extension. 20 March 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "5 reasons to try foodscaping your lawn". SaveOnEnergy.com. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Rousseau, Nicolas (17 October 2016). "Grouping Vegetables According to Plant Families | Louis Bonduelle..." Fondation Louis Bonduelle. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "Plants Portal | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Long, Jim. "The Pioneer of Edible Landscapes". Mother Earth Gardener, 2012, www.motherearthgardener.com/profiles/people/edible-landscapes-zmaz12uzfol. Accessed 13 April 2020.

- ^ Drotleff, Laura. "Foodscaping Challenges Conventional Ideas About Landscaping". Greenhouse Grower, 9 December 2015, www.greenhousegrower.com/management/foodscaping-challenges-conventional-ideas-about-landscaping/. Accessed 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Explore the château and gardens of Villandry". 1 February 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ a b c Oberst, Lindsay (12 September 2018). "Edible Landscapes: 15 Organizations Around the World That Are Helping Turn Green Spaces and Yards into Places for Healthy, Fresh Food". Food Revolution Network. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Kirschner, Kylie. "Edible Landscapes in a Concrete Jungle". Washington Square News, 24 Mar 2019, nyunews.com/culture/dining/2019/03/25/nyu-urban-landscaping-efforts/. Accessed 16 March 2020.

- ^ Sjauw En Wa, Amar. "Roof fields, Schieblok Rotterdam". Urban Green-Blue Grids, www.urbangreenbluegrids.com/projects/roof-fields-schieblok-rotterdam/. Accessed 5 May 2020.