Epioblasma brevidens

| Epioblasma brevidens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Bivalvia |

| Order: | Unionida |

| Family: | Unionidae |

| Genus: | Epioblasma |

| Species: | E. brevidens

|

| Binomial name | |

| Epioblasma brevidens (I. Lea, 1831)

| |

| |

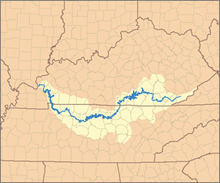

| The Cumberland River | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Dysnomia brevidens I. Lea, 1831 | |

Epioblasma brevidens, the Cumberlandian combshell, is a species of freshwater mussel, an aquatic bivalve mollusk in the family Unionidae. This species is endemic to the United States, found mainly in the states of Tennessee and Virginia. This mussel resides in medium-sized streams to large rivers. The combshell is an endangered species and protected under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA). The combshell is threatened by habitat modifications and pollution.

Description and physical characteristics

[edit]

The Cumberlandian combshell (Epioblasma brevidens) is a brown and yellow mussel that is about two inches (5.1 cm) long. Its shell has a yellow and brown film-like coating. The shell also has many green rays on it. The inside of the mussel is pearl-white. Female combshells also have serrated teeth-like structures around the edge of their shell, which appears inflated. These mussels live in shoals and in coarse sand and boulders in medium streams to large rivers. Combshells tend to live in depths of less than three feet (0.91 m). Sometimes combshells live in greater depths as found in the Old Hickory Reservoir on the Cumberland River. Being filter feeders, they feed on bacteria, diatoms, phytoplankton, zooplankton, some protozoans and detritus.[4]

Behavior

[edit]Juvenile combshells are suspension/deposit feeders. This means that they allow water to flow through their gills, but are not actively pumping water in. They also pedal feed, where they use cilia on their feet to drag in food particles to eat.[5] They feed on many microorganisms in streams and rivers.

Diet

[edit]The diet of mussels is fairly similar during different developmental stages. For the first two weeks of life, considered the juvenile stage, mussels like the combshell are considered suspension or deposit feeders. As they progress into adulthood, mussels become filter feeders, actively obtaining oxygen and nutrients from the water around them. Both juvenile and adult mussels consume bacteria, algae, diatoms, some detrital, and inorganic colloidal particles. Though bacteria make up an important part of the adult mussels diet, there is no evidence to suggest that it is important for the development of juvenile mussels. Additionally, adult mussels often feed on phytoplankton, zooplankton, phagotrophic protozoans, and other organic material in the water. Though algae are the most abundant food source found in the gut of mussels, and also provide key nutrients, algae do not contribute heavily to the mussels soft tissue stores.[4]

Life history

[edit]The combshell females nurture their eggs for a rather long time. This usually lasts from late summer to late spring. These eggs grow modified sections of their gills called “marsupia”. The eggs then develop into bivalved parasitic larvae called “glochidia”. Glochidia then attach to different types of fish where they become juvenile mussels. This usually occurs between 16 and 45 days[4]

Reproduction

[edit]During reproduction, the glochidium attaches to the gills or fins of a fish to complete its development. The larvae attach to several native host fish species, including several types of darter fish and sculpins. Female mussels produce large numbers of larvae but few juveniles find a fish host and even fewer survive to maturity. Glochidia transform into juvenile mussels after their attachment on these fish. This reliance between mussels and fish means that the combshell needs a healthy fish population to survive.[4]

Habitat and populations

[edit]Habitat

[edit]The Cumberlandian combshell has preferences for medium-sized streams to large rivers and is rarely found in small streams or tributaries. Within these waterways, the combshell is found in coarse sand, gravel, cobble, and boulders. Though it prefers to be in waters that are three feet deep or less, it is also found in some deeper waters, like Old Hickory Reservoir on the Cumberland River, where the water flow is strong.

Critical habitat

[edit]Combshells’ critical habitat under the ESA consists of:

- Three streams in the Cumberland River watershed:

- Buck Creek, Pulaski County, KY;

- Big South Fork, Scott County, TN;

- McCreary County, KY

- Seven streams in the Tennessee River watershed:

- Clinch River, Scott County, VA (this is where they are most prevalent);

- Hancock County, TN;

- Powell River, Lee County, VA;

- Claiborne/Hancock counties, TN;

- Bear Creek, Colbert County, AL;

- Tishomingo County, MS.[4]

Historical and present range

[edit]Historically the Cumberlandian combshell was found in a multitude of places. This included Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia. Within these states, combshells were found in three distinct areas of geography: The Interior Low Plateau, the Cumberlandian Plateau, and the Ridge and Valley.[6] According to a study done by Neel and Allen, the combshell was “very common” in the upper Cumberland River below Cumberland Falls in the late 1940s.[7] Yet, studies done by Ortmann reported it as prominent in the upper Tennessee River system but rare in the lower Tennessee and Cumberland River systems.[8] By 1980, the species was considered ‘extremely rare’ in its historical environments.[9] Current populations are only found in small numbers in Northeast Mississippi and in Southwest Virginia. The majority of the species are found in Tennessee and Kentucky in the Cumberland and Tennessee River basin.

Historical and present population size

[edit]There are no historical estimates of Cumberlandian combshell population size. The Cumberlandian combshell was ‘very common’ in the upper Cumberland River in the 1940s.[7] Since then, mainstream populations are considered to be essentially gone.[9] Threats to the species have put an immense burden on their populations, which have led the combshells population to dwindle. Populations are limited to 5 rivers as compared to its historic range. In the 1980s, studies placed the abundance of the combshell at around 0.01-0.03 mussels per square foot within sites in the Powell and Clinch Rivers. Current population sizes are below the effective population size, which threatens genetic diversity. Loss of genetic diversity can make a species more vulnerable to diseases, caused by bacteria, viruses, and parasites.[4]

Currently, several waterways, including the Clinch River, Powell River, and the Big South Fork National River, seem to show fairly stable populations of the combshell, but this is not true for other sites where the combshell is found.[4] In 2016, the Wolf Creek National Fish Hatchery successfully raised 521 Cumberlandian combshells to be released into the upper Cumberland and Licking River basins. This number more than doubled the population of combshells believed to currently exist in the Big South Fork of the Cumberland Rivers. In 2017, 706 mussels were raised to be released into these systems.[10] Scientists have also grown populations of mussels to be tagged, released, and recaptured in order to identify combshell survival rates in their natural habitat, as well as growth curves for the species.[11]

Conservation and threats

[edit]Major threats

[edit]Population size

[edit]The small population sizes of the combshell put the species at high risk for extinction. Because the surviving populations are also physically isolated, there is less chance for genetic mixing (through reproduction) between the populations. This could threaten the population's ability to adapt to natural or man-made challenges.[6]

Water pollution

[edit]The Tennessee Valley Authority and the US Army Corps of Engineers created impoundments on the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers, beginning in 1971. Many of the Cumberlandian combshell's historic populations were lost when this occurred. Combshells are not known to survive in waters that have been altered by dams. This is because the dams permanently change the free-flowing aquatic habitat that the combshell and their fish host species require. Other populations were lost due to water pollution and siltation. The combshell is particularly vulnerable to pollution from coal mining and poor land-use practices. Also, as urbanization increases, the chances of pollution from nonpoint sources has increased drastically. Combshell populations are currently at extreme risk for extinction by naturally occurring events. The Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) have defined naturally occurring events as things such as toxic chemical spills.[3]

Fish host

[edit]The same threats posed to the combshell also affect the fish that act as the hosts during juvenile maturation. As host populations decline, it becomes harder for the combshell to reproduce successfully.

Invasive species

[edit]One of the largest threats to the combshell is the invasive species known as the zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha). Originally native to the lakes of southern Russia and Ukraine, the Zebra mussel was introduced into the rivers of North America in 1988. The zebra mussel and the Cumberlandian combshell fight for the same resources, which puts additional strain on the already threatened combshell species.[4]

Human impacts

[edit]Humans have been a primary cause of habitat loss for the Cumberlandian combshell. Human factors, called anthropomorphic factors, that have affected the habitat include impoundments (artificially constructed water bodies), channelization (widening or deepening of river sections to increase the capacity for flow volume), water pollution and sedimentation (often due to soil runoff).

Though historically, humans have negatively affected this species, work is currently being done to right these wrongs. Listing the combshell as an endangered species offers protections that in theory should help the species recover. As an endangered species, a recovery plan has been written for the combshell. Though the combshell does not have its own individual recovery plan, it has been included in a recovery plan for several species. The Cumberlandian combshell, which was listed as threatened in 1991, and endangered in 1997, was not included in a recovery plan until 2004. The Cumberlandian combshell has also been given designated critical habitat, meaning that no development that would modify or destroy said habitat is allowed. The combshell also received a 5-year review in 2005 and 2018, tracking how conservation efforts and human intervention have affected populations.[4]

Endangered Species Act listing

[edit]The Cumberlandian combshell was officially given the status of endangered in 1997 under the Endangered Species Act. The Fish and Wildlife Services cited the decrease in range and population numbers as its reason for listing it as endangered. The species was first put up for protection under the act in 1991 but it was not finalized until January 10, 1997.[4] At the time of its listing, the Fish and Wildlife Service said that it had no plans to designate critical habitats for the combshell, but it did so in 2004.[6] These habitats were the Duck River in Tennessee, Bear Creek in Alabama and Mississippi, Powell River in Tennessee and Virginia, Clinch River in Tennessee and Virginia, Nolichucky River in Tennessee, Big South Fork in Tennessee and Kentucky, and Buck Creek in Kentucky.

Listing reasons

[edit]Conservation scientists first listed combshells on the endangered list in 1984. At that time, scientists considered combshells as possibly endangered or threatened. Scientists listed them again at this rank in 1989 and 1991. By 1994, scientists proposed that the Cumberlandian combshell be considered legally endangered.[12] Currently, they are listed as critically endangered.[1]

Channel modifications negatively affect combshell populations. This has happened with dams and mining in the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. Other threats, such as habitat loss/fragmentation and pollution, can harmfully affect Combshell populations as well. They are tied to fish populations. So, when fish populations change, so do combshells. The local and US government appropriated about 20% of the Tennessee River in 1971. This led to combshells’ demise starting in 1984.

Current conservation efforts

[edit]According to the recovery plan for the Cumberlandian combshell, the species will be delisted when distinct and viable populations can be found in at least nine streams, up from the five streams that the species is currently found in. In the combshells recovery plan, it is emphasized that ecosystem management, rather than individual species management, is the most effective method of protecting a wide array of species. The Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society was created in order to address mussel conservation.[6]

The Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources Center for Mollusk Conservation raises combshells for release into their natural habitat.[10]

On June 25, 2019, a permit was submitted to conduct presence/absence studies of the combshell in Big South Fork National River.[13] On February 20, 2020, an application was submitted by another party, looking to perform presence/absence studies throughout several different states.[14] There is not much information about Cumberlandian combshell conservation available on the internet, though the Fish and Wildlife Services highlights several ways common citizens can help, including limiting pesticide use, planting trees to prevent soil runoff, conserving energy to prevent the construction of new hydroelectric plants and removing aquatic weeds from boat trailers and engines.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Bogan, A.E.; Mollusc Specialist Group (2000). "Epioblasma brevidens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2000: e.T7865A12859056. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2000.RLTS.T7865A12859056.en. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ "Cumberlandian combshell (Epioblasma brevidens)". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ a b Biggins, Richard G.; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (1997-01-10). "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Determination of Endangered Status for the Cumberland Elktoe, Oyster Mussel, Cumberlandian Combshell, Purple Bean, and Rough Rabbitsfoot". Federal Register. 62 (7): 1647–1657. 62 FR 1647

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Cumberland combshell". Southeast Region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 12 September 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021.

- ^ "About Freshwater Mussels | Pacific Northwest Native Freshwater Mussel Workgroup". pnwmussels.org. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ a b c d "Recovery Plan" (PDF).

- ^ a b Institute of Malacology. (1962). Malacologia. Vol. 1 (1962-1964). [Ann Arbor: Institute of Malacology].

- ^ Ortmann, A. E. (1925). "The Naiad-Fauna of the Tennessee River System Below Walden Gorge". The American Midland Naturalist. 9 (8): 321–372. doi:10.2307/2992763. ISSN 0003-0031. JSTOR 2992763.

- ^ a b Terwilliger, Karen (1991). Virginia's endangered species : proceedings of a symposium. Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries. Blacksburg, Va.: McDonald and Woodward. ISBN 0-939923-16-5. OCLC 23973339.

- ^ a b Kirk, Sheila (January 30, 2018). "2017 mussel harvest in Kentucky is a success". Southeast Region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- ^ Hua, D; Jiao, Y; Neves, R; Jones, J (2016-12-30). "Periodic growth and growth cessations in the federally endangered freshwater mussel Cumberlandian combshell using a hierarchical Bayesian approach". Endangered Species Research. 31: 325–336. doi:10.3354/esr00773. hdl:10919/104364. ISSN 1863-5407.

- ^ "Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 7" (PDF).

- ^ "Endangered Species; Recovery Permit Applications". Federal Register. 2019-06-25. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- ^ "Endangered Species; Recovery Permit Applications". Federal Register. 2020-02-20. Retrieved 2020-04-19.