Bible translations into Dutch

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2008) |

Bible translations into Dutch have a history that goes back to the Middle Ages. The oldest extant Bible translations into the Dutch language date from the Middle Dutch (Diets) period.

Abbreviations

[edit]Bible translations are commonly referred to by their abbreviations, such as Psalm 55:22 (NBV), in which "NBV" stands for Nieuwe Bijbelvertaling ("New Bible Translation", 2004). The table below gives an overview of commonly used translations abbreviations:

|

|

|

History

[edit]Oldest partial translations

[edit]Several partial translations of the Bible into Old Dutch and Middle Dutch have been handed down in manuscripts. All these Medieval translations were made from Latin, usually the Latin Vulgate, the official version employed by the Catholic Church. After the early Medieval Christianisation of the language area of Old Dutch (Old Low Franconian), the entire populace was nominally Catholic, but very few were literate, let alone in Latin.

The Wachtendonck Psalms could be considered the oldest known biblical fragments in 'Dutch'. Although found in Munsterbilzen Abbey by Flemish humanist Justus Lipsius in the late 16th century, these texts most likely originated in the Dutch–German borderlands between the Meuse and Rhine rivers in the 9th or 10th century.[1] Although the texts' language is Old Dutch, Psalms 1 to 3 show clear Central Franconian characteristics.[2] It is generally assumed that the texts as handed down are an Old Dutch redaction of a Central Franconian original.[1] Another contender is the Rhinelandic Rhyming Bible, a series of fragments of biblical histories translations into an apparent mix of Old High German, Old Saxon, and Old Dutch from the early 12th century. However, due to the paucity of evidence, it's difficult to date, linguistically classify and geographically pinpoint the origins of these writings; although a number of scholars associate it with the German Rhineland, possibly the Werden Abbey, this remains undetermined.[3][4]

The oldest partial translation which can with certainty be called 'Dutch' is the Southern Netherlands Gospel Translation. This text is only attested in four 14th-century manuscripts, but probably dates from around 1200. C.C. de Bruin (1935) concluded that it was an example of a very poor translation of the four canonical gospels from the Latin Vulgate: he thought that the author likely neither mastered Latin nor his own native tongue in writing. Later scholars developed more nuanced positions; this gospel translation might just have been a tool for Latin-knowing clerics to explain to their congregations the texts' meaning in the vernacular. It was not meant to be read by or in front of the general public, as the liturgical language was Latin.[5][6]

Advanced and first printed translations

[edit]

A later example is the Rijmbijbel of Jacob van Maerlant (1271), a poetic edition of the Petrus Comestor's Historia scholastica (c. 1173). It was not a literal translation, but a so-called "history Bible": a freely translated compilation of texts from the "historical books" of the Bible mixed with extrabiblical sources and traditions. Another example is the Liégeois Leven van Jesus ("Life of Jesus"), a gospel harmony based on Tatian's Latin Diatessaron. This "Liège Diatessaron", which was of comparatively high quality next to many poor translations, was most likely produced around 1280 in the entourage of Willem van Affligem, the abbot of Sint-Truiden Abbey.[8]

Several Middle Dutch translations of the Apocalypse of John, the Psalms, the Epistles and the Gospels appeared in Flanders and Brabant at the end of the 13th and the beginning of the 14th century.[8] Later, the entourage of Brabantian mystic John of Ruusbroec (1293–1381) produced a full translation of all non-historical books of the New Testament.[8] Evidence suggests that such late Medieval Dutch translations were in widespread use in the Low Countries and the German Rhineland amongst monks, nuns and wealthy burghers.[8]

The first nearly complete Middle Dutch translation from the Latin Vulgate was the Hernse Bijbel or Zuid-Nederlandse Historiebijbel ("Southern Netherlands History Bible"). It was probably made at the Carthusian monastery in Herne, Belgium, in the second half of the fourteenth century, probably in 1360. Scholars refer to the anonymous author as the "Bible translator of 1360"; some identify Petrus Naghel as the translator, but others are not convinced. Around 1390, an anonymous "Northern Netherlands New Testament Translation" also emerged: the oldest surviving manuscript from 1391 had no gospels, but a 1399 manuscript contains the entire New Testament. Scholars find it highly probable that it was written by the Windesheim monk Johan Scutken (died 1423).[9][10]

The Hernse Bijbel served as a template for the oldest print translation of Biblical books into the Middle Dutch language: the Delft Bible (Delftse Bijbel), printed in Delft in 1477. This translation from the Latin Vulgate only included the Old Testament with Apocrypha but without the Psalms. Around the same time, parts of the history Bible of Johan Scutken were also printed: the Epistelen en evangeliën ("Epistles and Gospels", first publication in Utrecht in 1478) and the Psalmen ("Psalms", first publication in Delft in 1480). Because the latter two satisfied the needs of most vernacular readers – primarily nuns in convents – no full Dutch Bible translation was ever printed before the Reformation.[8]

Reformation era translations

[edit]

During the sixteenth century the Liesveltbijbel (first ed. 1526, Antwerp, many later editions), Biestkensbijbel (1560) and the Deux-Aesbijbel (1562, Emden) were produced. These editions were all Protestant and therefore unauthorised, as a result their availability would have been poor at times. An authorised Catholic translation based on the Latin Vulgate to counter the Textus Receptus favoured by Protestants was also produced, the Leuvense Bijbel (1548, Louvain). These were the oldest print translations of the entire Bible into Dutch. The Vorstermanbijbel (Antwerp, 1528 several later editions) was a semi-authorised version with a mix of Latin Vulgate and Textus Receptus translations that is difficult to classify as either 'Catholic' or 'Protestant'; later editions generally removed Reformationist passages and followed the Vulgate ever more closely, aligning it more with Catholicism.

Philips of Marnix, Lord of Saint-Aldegonde (1538–1598), who was among the leaders of the Dutch Revolt, and Pieter Datheen were tasked in 1578 by the second national synod of the Reformed church in Dort to produce a translation into Dutch, although this did not result in a translation.[11] Philips of Marnix was again asked to translate the Bible in 1594 and 1596, but he was unable to finish this work before he died in 1598. His translation influenced the later Statenvertaling or Statenbijbel.

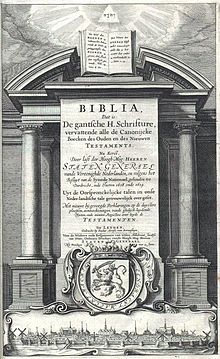

The first authorised Bible translation into Dutch directly from Greek (using the Textus Receptus) and Hebrew sources was the Statenvertaling. It was ordered by the States-General of the emerging Dutch Republic at the Synod of Dort in 1618/19, and first published in 1637. It soon became the generally accepted translation for the Calvinist Reformed Churches in the Northern Netherlands and remained so well into the 20th century. It was supplanted to a large extent in 1951 by the Nederlands Bijbelgenootschap (NBG) translation, better known as NBG 1951, which still uses relatively old-fashioned language.

Lutherans in the Dutch Republic employed the Biestkensbijbel since 1560, but there was a need for a proper Dutch translation of the Luther Bible (written in High German) to preserve their identity vis-à-vis the Statenvertaling that was deemed too Calvinist, and to provide immigrated Lutheran Germans with an appropriate Dutch translation. To this end, a translation commission was set up in 1644 headed by the Lutheran preacher Adolph Visscher (1605–1652), resulting in the Lutheran translation of 1648. Although the preface claimed it was a new translation, this was in fact not the case. Nevertheless, this version became so well-known amongst Dutch Lutherans and the later Evangelical Lutheran Church in the Kingdom of the Netherlands (1818–2004) as an exceptional translation associated with the commission's president that it became known as the "Visscherbijbel". After 1951, most Lutherans switched to the NBG 1951.[12]

Modern translations

[edit]In order to replace the outdated Statenvertaling with a more accurate, modern, critical edition that was acceptable to all Protestant churches in the Netherlands, the Nederlands Bijbelgenootschap (NBG, "Dutch Bible Society") set up two commissions with experts and representatives from most denominations to produce the NBG 1951, which would grow to become the new Protestant standard for the second half of the 20th century. Most Calvinist and Lutheran congregations adopted it. Only a minority of conservative Calvinist churches rejected it, favouring the old Statenvertaling instead. Catholics developed their own alternative, the Willibrordvertaling (1961–1978, authorised by the Catholic Church); the 1995 second edition was never authorised by the Catholic Church, but a special edition of it with a 'Protestant' ordering of chapters was adopted by a few Protestant churches. Some other examples of modern Dutch language translations are Groot Nieuws Bijbel (GNB, 1996), and the International Bible Society's Het Boek (1987).

In 2004, the Nieuwe Bijbelvertaling (NBV) translation appeared, which was produced by an ecumenical translation team, and is intended as an all-purpose translation for pulpit and home use. It is a critical, Alexandrian text-type version, based on the 27th Nestle–Aland edition of 2001. However, some theologians levelled criticism on its accuracy.[13] Around the same time, there has also been much work on very literal, idiolect translations, such as the Naarden translation of 2004, Albert Koster's translation of the Old Testament, a work in progress since 1991, and the Torah translation of the Societas Hebraica Amstelodamensis.[citation needed] In December 2010, the Herziene Statenvertaling ("Revised States Translation") was released. It essentially replicates the Statenvertaling of 1637 into modern Dutch, and was produced by conservative Protestants who maintained that the Byzantine Textus Receptus was superior to the Alexandrian text-type that modern scholars used for critical editions, such as the 2004 Nieuwe Bijbelvertaling.

In October 2014, the Bijbel in Gewone Taal ("Bible in Normal Language") was released.[14]

Comparison

[edit]| Year | Translation and background | Genesis 1:1–3 | John (Johannes) 3:16 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1271 | Rijmbijbel (Jacob van Maerlant)

Catholic. Not a literal translation, but a poetic "history Bible" based on Petrus Comestor's Latin Historia scholastica |

[God die maecte int beghin / Den hemel ende oec mede der in / Alle die inghelike nature / Desen hemel heet die scrifture / (...) ende hi maecte die erde mede / (...) Ende met deemstereden bedect / die scrifture die vertrect / dat die eleghe gheest ons heren / dats gods wille dus salment keeren / die wart up water ghedraghen / (...) DOe maecte god met sinen worde / dat lecht alse hict bescriuen hoerde /] | – |

| 1477 | Delftse Bijbel

Catholic, based on the Latin Vulgate. First printed Dutch translation, Old Testament (excluding Psalms) only. |

INden beghin sciep god hemel ende aerde. Mer die aerde was onnut ende ydel: ende donckerheden waren op die aensichten des afgronts. Ende goods gheest was ghedraghen bouen den wateren. Ende god seide dat licht moet werden: ende dat licht wort ghemaect[15] | – |

| 1526– 1542 |

Liesveltbijbel

Protestant (Lutheran). First fully printed Dutch Bible translation. NT based on Luther's 1522 September Bible (in turn based on Erasmus' 1519 Textus Receptus); OT based on Luther's unfinished translation, the Latin Vulgate and other translations. Liesvelt was executed for his 'heretical' editions in 1545.[16] |

[1542 edition] INden beginne schiep God hemel ende aerde, [1] ende dye aerde was woest ende leech, ende het was doncker opten afgront. Ende Gods geest dreef op den watere. Ende God sprack, Het worde licht, ende het werdt licht,[17] | † Alsoo heeft God die [11] werelt bemint, dat hi sinen eenighen sone gaf, op dat alle die in hem geloouen, nyet verloren en worden, mer dat eewich leuen hebben[18] |

| 1528– 1548 |

Vorstermanbijbel

Mixed version authorised by secular authorities. 1528 OT based on 1526 Liesveltbijbel, NT on Luther's 1522 September Bible. 1531 NT derived from Erasmian Textus Receptus. Later editions increasingly relied on Latin Vulgate until all Vorstermanbijbels were banned by the Catholic Church in 1548. |

[1531 edition] INden beghinne schiep God * hemel ende aerde.) Ende die aerde was * ydel) ende ledich, ende die duysternissen waren opt aensicht des afgronts Ende Gods * gheest) dreef opt * watere.) Ende God sprack, Latet licht gemaect worden, Ende het licht wert gemaect,[19] | Want also heeft god die werelt bemint dat hi zijn eenige geboren soon gegeuen heeft op dat al die gene die in hem gelooft, nyet en vergae, mer hebbe dat eewighe leuen.[20] |

| 1548 | Leuvense Bijbel

Catholic version authorised by the Catholic Church based on the Latin Vulgate to counter Textus Receptus-based Protestant translations. |

INDEN beginne heeft Godt geschapen hemel ende aerde, maer die aerde was ydel ende ledich, ende die duysternissen waren op dat aenschijn des afgronts, ende den gheest Godts dreef op die wateren. Ende Godt heeft geseyt, Laet gemaect worden het licht. Ende het licht worde gemaect, | Want alsoe lief heeft Godt die werelt ghehadt dat hy sijnen eenighen sone ghegheuen heeft op dat alle die in hem ghelooft niet en vergae, maer hebbe dat eewich leuen. |

| 1560 | Biestkensbijbel

Protestant (Baptist/Lutheran) version with strong similarities to a 1558 version published in Emden, which in turn was largely based on a 1554 High German Luther Bible printed in Magdeburg. Changes, references, emphases and notes point to Mennonite influence.[21] |

INden beginne† schiep Godt Hemel ende Aerde. Ende de Aerde was woest ende ledich, ende het was duyster op der diepte, ende de Geest Gods* sweefde op den watere. † Ende God sprack: Het worde Licht. Ende het wert Licht, | * Alsoo lief heeft God de Werelt gehadt, dat hy sinen eenighen Soon gaf,† op dat alle die aen hem gheloouen, niet verloren en worden, maer dat eewich leuen hebben. |

| 1562 | Deux-Aesbijbel

Calvinist translation during the Protestant Reformation, based on the 1526 (Lutheran) Liesveltbijbel and 1534 Luther Bible, which derived from the Textus Receptus. |

IN dena beginne sciep God Hemel ende Aerde. Ende de Aerde was woest ende ledich, ende het was duyster op den afgront, ende de b geest Gods sweuede opt water. Ende God sprack: Het worde licht: ende het wert licht. | Want also lief heeft God de werelt gehadt, dat hy synen eenichgheboren Sone ghegheuen heeft, r op dat een yeghelick die in hem gelooft, [volgende kolom] niet verderue, maer het eewighe leuen hebbe: |

| 1637 | Statenvertaling (SV)

Calvinist (de facto), authorised by the Dutch Republic government. Old Testament based on Masoretic Text, consulting the Septuagint. New Testament heavily dependent on the Textus Receptus, a Byzantine text-type. |

In den beginne schiep God den hemel en de aarde. De aarde nu was woest en ledig, en duisternis was op den afgrond; en de Geest Gods zweefde op de wateren. En God zeide: Daar zij licht: en daar werd licht. | Want alzo lief heeft God de wereld gehad, dat Hij Zijn eniggeboren Zoon gegeven heeft, opdateen iegelijk die in Hem gelooft, niet verderve, maar het eeuwige leven hebbe. |

| 1648 | Visscherbijbel

Lutheran translation derived from the Luther Bible, which used the Textus Receptus (a Byzantine text-type) for the New Testament.[12] |

IN’t begin schiep Godt Hemel ende Aerde.[1] Ende de aerde was woest ende ledigh, ende het was duyster op de diepte, ende dea Geest Godts sweefde op ’t water. Ende Godt sprack: Het worde licht. Ende het wiert licht.[22] | ► Alsoo lief heeft Godt de Werelt gehadt, dat Hy sijnen eenigh-geborenen Soon gaf; op dat alle die in Hem gelooven, niet verloren en worden, maer het eeuwige leven hebben ←.[23] |

| 1951 | Nederlands Bijbelgenootschap 1951 (NBG 1951)

Protestant interconfessional critical edition. Old Testament based on the Masoretic Text of Codex L, New Testament based primarily on the Alexandrian text-type. |

In den beginne schiep God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde nu was woest en ledig, en duisternis lag op de vloed, en de Geest Gods zweefde over de wateren. En God zeide: Er zij licht; en er was licht. | Want alzo lief heeft God de wereld gehad, dat Hij zijn eniggeboren Zoon gegeven heeft, opdat een ieder, die in Hem gelooft, niet verloren ga, maar eeuwig leven hebbe. |

| 1969 | Nieuwe-Wereldvertaling van de Heilige Schrift (NW)

Derived from the English Jehovah's Witnesses translation 1950–1961. First edition (using Westcott and Hort) was deemed unscholarly and theologically distorted; later editions (1970, 1984) were based on Nestle-Aland's text. |

In [het] begin schiep God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde nu bleek vormloos en woest te zijn en er lag duisternis op het oppervlak van [de] waterdiepte; en Gods werkzame kracht bewoog zich heen en weer over de oppervlakte van de wateren. Nu zei God: „Er kome licht.” Toen kwam er licht. | Want God heeft de wereld zozeer liefgehad dat hij zijn eniggeboren Zoon heeft gegeven, opdat een ieder die geloof oefent in hem, niet vernietigd zou worden, maar eeuwig leven zou hebben. |

| 1975– 1995 |

Willibrordvertaling (WV)

Catholic translation |

In het begin schiep God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde was woest en leeg; duisternis lag over de diepte, en de geest van God zweefde over de wateren. Toen zei God: ‘Er moet licht zijn!’ En er was licht. | Zoveel immers heeft God van de wereld gehouden, dat Hij zijn eniggeboren Zoon heeft geschonken, zodat iedereen die in Hem gelooft niet verloren gaat, maar eeuwig leven bezit. |

| 1983– 1996 |

Groot Nieuws Bijbel (GNB)

Ecumenic translation |

In het begin schiep God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde was onherbergzaam en verlaten. Een watervloed bedekte haar en er heerste diepe duisternis. De wind van God joeg over het water. Toen zei God: ‘Er moet licht zijn!’ En er was licht. | Want God had de wereld zo lief dat hij zijn enige Zoon gegeven heeft, opdat iedereen die in hem gelooft, niet verloren gaat maar eeuwig leven heeft. |

| 1987 | Het Boek (HTB)

Protestant edition in simple Dutch by the Dutch branch of the International Bible Society. |

In het begin heeft God de hemelen en de aarde gemaakt. De aarde was woest en leeg en de Geest van God zweefde boven de watermassa. Over de watermassa lag een diepe duisternis. Toen zei God: "Laat er licht zijn." En toen was er licht. | Want God heeft zoveel liefde voor de wereld, dat Hij Zijn enige Zoon heeft gegeven; zodat ieder die in Hem gelooft, niet verloren gaat maar eeuwig leven heeft. |

| 2004 | Nieuwe Bijbelvertaling (NBV)

Ecumenic critical edition. Old Testament based Masoretic Text (Codex L), Deuterocanonicals based on Göttinger Septuaginta 1931, New Testament based on the Alexandrian text-type (27th Nestle-Aland 2001).[24] |

In het begin schiep God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde was nog woest en doods, en duisternis lag over de oervloed, maar Gods geest zweefde over het water. God zei: ‘Er moet licht komen,’ en er was licht. | Want God had de wereld zo lief dat hij zijn enige Zoon heeft gegeven, opdat iedereen die in hem gelooft niet verloren gaat, maar eeuwig leven heeft. |

| 2010 | Herziene Statenvertaling (HSV)

Calvinist conservative Statenvertaling retranslation. Old Testament based on Masoretic Text, consulting the Septuagint and the Dead Sea Scrolls. New Testament heavily dependent on the Textus Receptus, a Byzantine text-type.[24] |

In het begin schiep God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde nu was woest en leeg, en duisternis lag over de watervloed; en de Geest van God zweefde boven het water. En God zei: Laat er licht zijn! En er was licht. | Want zo lief heeft God de wereld gehad, dat Hij Zijn eniggeboren Zoon gegeven heeft, *opdat ieder die in Hem gelooft, niet verloren gaat, maar eeuwig leven heeft. |

| 2013 | BasisBijbel (BB)

Protestant Statenvertaling retranslation by the Pocket Testament League. New Testament heavily dependent on the Textus Receptus, a Byzantine text-type. |

In het begin maakte God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde was helemaal leeg. Er was nog niets. De aarde was bedekt met water en het was er helemaal donker. De Geest van God waaide over het diepe water. En God zei: "Ik wil dat er licht is!" Toen was er licht. | Want God houdt zoveel van de mensen, dat Hij zijn enige Zoon aan hen heeft gegeven. Iedereen die in Hem gelooft, zal niet verloren gaan, maar zal het eeuwige leven hebben. |

| 2014 | Bijbel in Gewone Taal (BGT)

Protestant critical edition in simple/paraphased modern Dutch. New Testament based on the Alexandrian text-type (28th Nestle-Aland 2012).[24] |

In het begin maakte God de hemel en de aarde. De aarde was leeg en verlaten. Overal was water, en alles was donker. En er waaide een hevige wind over het water. Toen zei God: ‘Er moet licht komen.’ En er kwam licht. | Want Gods liefde voor de mensen was zo groot, dat hij zijn enige Zoon gegeven heeft. Iedereen die in hem gelooft, zal niet sterven, maar voor altijd leven. |

References

[edit]- ^ a b Arend Quak, Die altmittel- und altniederfränkischen Psalmen und Glossen (1981). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- ^ Arend Quak, Joop van der Horst, Inleiding Oudnederlands (2002). Leuven: Universitaire Pers Leuven. ISBN 90-5867-207-7.

- ^ David A. Wells, The Central Franconian Rhyming Bible: An Early-Twelfth-Century German Vers Homiliary (2004), p. 282. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi B.V.

- ^ Helmut Tervooren, Van der masen tot op den Rijn (2006), p. 45–47. Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag.

- ^ Theo Coun, De Zuid-Nederlandse vertaling van de vier evangelien in Gillaerts, Paul (red.) De Bijbel in de Lage Landen (2015), Royal Jongbloed.

- ^ Frits van Oostrum, Stemmen op schrift. Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse literatuur vanaf het begin tot 1300 (2006). Bert Bakker.

- ^ "Rijmbijbel [fragment]". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Encarta Winkler Prins Encyclopaedia (1993–2002) s.v. "bijbel § 3.1 Bijbelvertalingen in het Nederlands". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- ^ Suzan Folkerts, "De Noord-Nederlandse vertaling van het Nieuwe Testament" in Paul Gillaerts (ed.) De Bijbel in de Lage Landen (2015). Royal Jongbloed.

- ^ Sabrina Corbellini, "De Noordnederlandse vertaling van het Nieuwe Testament. Het paradijs in een kloostercel" in Kwakkel, Den Hollander, Scheepsma (ed.) Middelnederlandse bijbelvertalingen (2007). Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren.

- ^ Selderhuis (ed), Handboek Nederlandse kerkgeschiedenis.

- ^ a b "Lutherse vertaling (1648)". bijbelsdigitaal.nl. Nederlands-Vlaams Bijbelgenootschap. 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ For instance the book Het luistert nauw by Karel Deurloo and Nico ter Linden.

- ^ "Feestelijke uitreiking Bijbel in Gewone Taal aan koning Willem-Alexander - Nederlands Bijbelgenootschap". 1 October 2014.

- ^ (transcription by Nicoline van der Sijs in 2008) (1477). "Delftse bijbel (1477): Genesis 1:1–1:22a". BijbelsDigitaal.nl (in Dutch). Nederlands–Vlaams Bijbelgenootschap. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Liesveltbijbel (1542)". BijbelsDigitaal.nl (in Dutch). Nederlands–Vlaams Bijbelgenootschap. 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ (transcription by Nicoline van der Sijs & Hans Beelen in 2010) (1542). "Liesveltbijbel (1542): Dat boeck Genesis 1:1–1:21a". BijbelsDigitaal.nl (in Dutch). Nederlands–Vlaams Bijbelgenootschap. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ (transcription by Nicoline van der Sijs & Hans Beelen in 2010) (1542). "Liesveltbijbel (1542): Sinte Ioannes Euangelie 3:5b–4:14a". BijbelsDigitaal.nl (in Dutch). Nederlands–Vlaams Bijbelgenootschap. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ (transcription by Nicoline van der Sijs & Hans Beelen in 2012) (1531). "Vorstermanbijbel (1528/1531): Dat boeck Genesis 1:1–1:11a". BijbelsDigitaal.nl (in Dutch). Nederlands–Vlaams Bijbelgenootschap. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ (transcription by Nicoline van der Sijs & Hans Beelen in 2012) (1531). "Vorstermanbijbel (1528/1531): Sinte Ians Euangelie 3:2b–4:3". BijbelsDigitaal.nl (in Dutch). Nederlands–Vlaams Bijbelgenootschap. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Biestkensbijbel (1560)". BijbelsDigitaal.nl (in Dutch). Nederlands–Vlaams Bijbelgenootschap. 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ (transcription by Nicoline van der Sijs & Hans Beelen in 2009) (1648). "Lutherse vertaling (1648): Genesis, Het I. Boeck Mose 1:1–1:21a". BijbelsDigitaal.nl (in Dutch). Nederlands–Vlaams Bijbelgenootschap. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ (transcription by Nicoline van der Sijs & Hans Beelen in 2009) (1648). "Lutherse vertaling (1648): Euangelium Iohannis 2:16b–3:26a". BijbelsDigitaal.nl (in Dutch). Nederlands–Vlaams Bijbelgenootschap. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Cor Hoogerwerf (November 2016). "Welk Nieuwe Testament?". bijbelgenootschap.nl (in Dutch). Nederlands-Vlaams Bijbelgenootschap. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

External links

[edit]- De Delfste Bijbel, the first Dutch Bible (1477)

- Another site with the same

- De Leuvense Bijbel, the second Dutch Bible (1548)

- Statenvertaling: full text, including the Apocrypha; 1977 edition

- UBS Biblija.net/BijbelOnline Bijbel Online: full text of Statenvertaling (Jongbloed-editie and 1977 edition), Nederlands Bijbelgenootschap, Groot Nieuws Bijbel, Willibrordvertaling, and De Nieuwe Bijbelvertaling

- BasisBijbel online

- Neff, Christian (1953). "Biestkens Bible". Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- Entry in Dutch Wikipedia