Drummer (military)

A drummer was responsible for the army drums for use on the battlefield. Drums were part of the battlefield for hundreds of years, being introduced by the Ottomans to Europe. Chinese armies, however, had used drums even before this. With the professionalization of armies, military music was developed as well. Drums were used for the men to march in step and were also an important part of the battlefield communications system, with various drum rudiments being used to signal different commands from officers to troops.[1] By the second half of the 18th century, most (if not all) Western armies had a standardized set of marches and signals to be played, often accompanied by fifers.

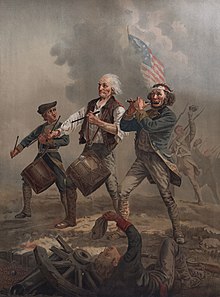

The idea of the "Drummer Boy"

[edit]The romantic idea about drummers is that they were young boys (for instance the Christmas carol "The Little Drummer Boy", or the painting "Steady the Drums and Fifes"). Drummers were more often adult men, recruited like the common soldiers. Fifers, on the other hand, being not an official part of the regiments early on, were usually recruited from young boys. During the second half of the 19th century, it was accepted in many western armies that under aged boys served as drummers.

Although there were usually official age limits, these were often ignored; the youngest boys were sometimes treated as mascots by the adult soldiers. The life of a drummer boy appeared rather glamorous and as a result, boys would sometimes run away from home to enlist.[2] Other boys may have been the sons or orphans of soldiers serving in the same unit.[3] The image of a small child in the midst of battle was seen as deeply poignant by 19th-century artists, and idealized boy drummers were frequently depicted in paintings, sculpture and poetry.[4]

Notable drummer boys

[edit]

Nathan Futrell (1773–1829) was said to have been the youngest drummer boy in the American War of Independence; he joined the North Carolina Continental Militia at the age of 7.

In 1793, Joseph Bara, a 14-year-old French Republican drummer at the time of the War in the Vendée, was killed by royalist counter-revolutionaries, supposedly while he was shouting "Long live the Republic!". His body was interred at the Panthéon along with other national heroes.[5]

André Estienne was a drummer with Napoleon Bonaparte's army at the Battle of the Bridge of Arcole in 1796, where he led his battalion across a river while holding his drum over his head, and on reaching the far bank, beat the "charge". This led to the capture of the bridge and the rout of the Austrian army. Despite being 19 years old, he became famous as Le Petit Tambour d'Arcole (French: The Little Drummer of Arcole), and is depicted in the Panthéon in Paris and on the Arc de Triomphe, also in paintings by Charles Thévenin and Horace Vernet.[6]

On 19 April 1855, at the Siege of Sevastopol during the Crimean War, there was a bayonet attack by the British 77th Regiment of Foot on some rifle pits which the Russians were using to snipe at British positions. Accompanying the attack was an unnamed drummer boy of the 77th, who seeing a Russian boy trumpeter trying to escape, caught hold of him and beat him with his fists "in truly British fashion" until he surrendered. The boy presented the Russian trumpet to Sir George Brown and he was later rewarded by General Lord Raglan, the British commander.[7]

At the Siege of Lucknow during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, 12-year-old Drummer Ross of the 93rd Highlanders signalled the arrival of his regiment to the besieged garrison, by climbing the spire of the Shah Najaf Mosque and playing the regimental march on his bugle, while under heavy fire from the rebel forces.[8]

On 28 November 1857 at the Second Battle of Cawnpore, 15-year-old Thomas Flynn, a drummer with the 64th Regiment of Foot, was awarded the Victoria Cross. "During a charge on the enemy's guns, Drummer Flynn, although wounded himself, engaged in a hand-to-hand encounter with two of the rebel artillerymen". He remains the youngest recipient of the medal.[9]

Thirteen-year-old Charles Edwin King was the youngest soldier killed in the entire American Civil War (1861–1865). Charles enlisted in the 49th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry with the reluctant permission of his father at the age of 12 years, 5 months and 9 days. On September 17, 1862 at the Battle of Antietam he was mortally wounded near or in the area of the East Woods, carried from the field and died three days later.

Twelve-year-old drummer boy William Black was the youngest recorded person wounded in battle during the American Civil War.

John Clem, who had unofficially joined a Union Army regiment at the age of 9 as a drummer and mascot, became famous as "The Drummer Boy of Chickamauga" where he played a "long roll" and shot a Confederate officer who had demanded his surrender.

An 11-year-old drummer in the Confederate Orphan Brigade, known only as "Little Oirish", was credited with rallying troops at the Battle of Shiloh by taking up the regimental colors at a critical moment.[10]

Decline

[edit]

The use of drums beyond the parade ground declined rapidly as the 19th century progressed, being replaced by the bugle in the signalling role, although it was often the drummers who were required to play them. A widely reported incident at the Battle of Isandlwana during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, spelled the end of boys being sent on active service by the British Army. Part of the British force returned to their camp at night to find that it had been overrun by the Zulu army a few hours previously. An eyewitness reported that "Even the little drummer boys that we had in the band, they were hung up on hooks, and opened like sheep. It was a pitiful sight". Doubt has since been cast on this account, since the youngest drummer to be killed was 18, and the youngest boy present was 16.[11] Despite this, Charles Edwin Fripp's famous painting, The Last Stand at Isandlwana, shows a small blond-haired boy amongst the adult soldiers.[12] The US Army kept drummers and fifers with the infantry, until they were finally abolished in the field in 1917. Drums, like other instruments, were now only used for parades and ceremonies.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ U.S. Civil War History & Genealogy – The Drummer Boys Archived 2021-05-14 at the Wayback Machine, genealogyforum.com

- ^ Albert A. Nofi, A Civil War Treasury: Being a Miscellany of Arms and Artillery, Facts and Figures, Legends and Lore Da Capo Press 1992 (p.107)

- ^ Richard Holmes, Soldiers: Army Lives and Loyalties from Redcoats to Dusty Warriors, Harper Press 2011 (p.275)

- ^ J. W. M. Hichberger, Images of the Army: The Military in British Art, 1815–1914, Manchester University Press 1988, ISBN 0-7190-2575-3 (p.101)

- ^ Dupuy, Pascal, La Mort de Bara http://www.histoire-image.org L’Histoire par l’image (in French). Retrieved: 19 January 2015

- ^ Fondation Napoléon – Honorary drumsticks presented to the drummer of Arcole Archived May 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thomas Carter, Medals of the British Army: and How They Were Won: Volume 1, Groombridge and Son, London 1861 (p.77)

- ^ Holmes, (p.275)

- ^ "Athlone Heritage – Drummer Thomas Flynn VC". Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ^ Nofi, (p.108)

- ^ Ian Knight, Zulu Rising: The Epic Story of iSandlwana and Rorke's Drift, Pan Books 2011 ISBN 978-0330445931

- ^ Ian Knight, Isandlwana 1879: The Great Zulu Victory, Osprey Publishing Limited 2002, ISBN 1-84176-511-2 (p.64)