Geography of Honduras

| |

| Continent | North America |

|---|---|

| Region | Central America |

| Coordinates | 15°00′N 86°30′W / 15.000°N 86.500°W |

| Area | Ranked 101st |

| • Total | 112,777 km2 (43,543 sq mi) |

| • Land | 99.82% |

| • Water | 0.18% |

| Coastline | 832 km (517 mi) |

| Borders | 1575 km (975 mi) |

| Highest point | Cerro Las Minas 2,870 metres (9,420 ft) |

| Lowest point | Caribbean Sea 0 metres (0 ft) |

| Longest river | Ulúa 400 km (250 mi) |

| Largest lake | Lake Yojoa 79 km2 (31 sq mi) |

| Exclusive economic zone | 249,542 km2 (96,349 sq mi) |

Honduras is a country in Central America. Honduras borders the Caribbean Sea and the North Pacific Ocean. Guatemala lies to the west, Nicaragua south east and El Salvador to the south west. Honduras is the second largest Central American republic, with a total area of 112,777 square kilometres (43,543 sq mi).

Honduras has a 700-kilometer (430-mile) Caribbean coastline extending from the mouth of the Río Motagua in the west to the mouth of the Río Coco in the east, at Cape Gracias a Dios.[1] The 922 km (573 mi) southeastern side of the triangle is a land border with Nicaragua.[1] It follows the Río Coco near the Caribbean Sea and then extends southwestward through mountainous terrain to the Gulf of Fonseca on the Pacific Ocean.[1] The southern apex of the triangle is a 153 km (95 mi) coastline on the Gulf Fonseca, which opens onto the Pacific Ocean.[1] In the west there are two land borders: with El Salvador as 342 km long (213 mi) and with Guatemala as 256 km long (159 mi).[1]

Topography

[edit]

Honduras has three distinct topographical regions: an extensive interior highland area and two narrow coastal lowlands.[1] The interior, which constitutes approximately 80 percent of the country's terrain, is mountainous.[1] The larger Caribbean lowlands in the north and the Pacific lowlands bordering the Gulf of Fonseca are characterized by alluvial plains.[1]

Interior highlands

[edit]The interior highlands are the most prominent feature of Honduran topography.[1] This mountain area makes up about 80% of the country's area, and is home to the majority of the population.[1] Because the rugged terrain has made the land difficult to traverse and equally difficult to cultivate, this area has not been highly developed.[1] The soil here is poor: Honduras lacks the rich volcanic ash found in other Central American countries.[1] Until the early 20th century, the highland economy consisted primarily of mining and livestock.[1]

In the west, Honduras' mountains blend into the mountain ranges of Guatemala.[1] The western mountains have the highest peaks, with the Pico Congolón at an elevation of 2,500 metres (8,202 ft) and the Cerro Las Minas at 2,850 m (9,350 ft).[1] The Honduran border with El Salvador crosses the peak of Cerro El Pital, the highest point in El Salvador at over 2,730 m (8,957 ft).[2] These mountains are woodland covered with mainly pine forests.[1]

In the east, the mountains merge with those in Nicaragua.[1] Although generally not as high as the mountains near the Guatemalan border, the eastern ranges possess some high peaks, such as the Montaña de la Flor at 2,300 m (7,546 ft), El Boquerón (Monte El Boquerón) at 2,485 m (8,153 ft), and Pepe Bonito at 2,435 m (7,989 ft).[1]

One of the most prominent features of the interior highlands is a depression that runs from the Caribbean Sea to the Gulf of Fonseca.[1] This depression splits the country's cordilleras into eastern and western parts and provides a relatively easy transportation route across the isthmus.[1] Widest at its northern end near San Pedro Sula, the depression narrows as it follows the upper course of the Río Humuya.[1] Passing first through Comayagua and then through narrow passes south of the city, the depression widens again as it runs along the border of El Salvador into the Gulf of Fonseca.[1]

Scattered throughout the interior highlands are numerous flat-floored valleys, at 300 to 900 meters (980 to 2,950 ft) in elevation, which vary in size.[1] The floors of the large valleys provide sufficient grass, shrubs, and dry woodland to support livestock and, in some cases, commercial agriculture.[1] Subsistence agriculture has been relegated to the slopes of the valleys, with the limitations of small-sized holdings, primitive technology, and low productivity that traditionally accompany hillside cultivation.[1] Villages and towns, including the capital, Tegucigalpa, are tucked in the larger valleys.[1]

Vegetation in the interior highlands is varied.[1] Much of the western, southern, and central mountains are open woodland; supporting pine forest interspersed with some oak, scrub, and grassy clearings.[1] The ranges toward the east are primarily continuous areas of dense, broad-leaf evergreen forest.[1] Around the highest peaks, remnants of dense rainforest that formerly covered much of the area are still found.[1]

Caribbean lowlands

[edit]This area of river valleys and coastal plains, which most Honduras call "the north coast," or simply "the coast," has traditionally been Honduras's most exploited region.[1] The central part of the Caribbean lowlands, east of La Ceiba, is a narrow coastal plain only a few kilometers wide.[1]

To the east and west of this section the Caribbean lowlands widen and in places extend inland a considerable distance along broad river valleys.[1] The broadest river valley, along the Río Ulúa near the Guatemalan border, is Honduras's most developed area.[1] Both Puerto Cortés, the country's largest port, and San Pedro Sula, Honduras's industrial capital, are located here, as is La Ceiba, the third largest city in the country.[1]

To the east, near the Nicaraguan border, the Caribbean lowlands broaden to an extensive area known as La Mosquitia.[1] Unlike the western part of the Caribbean lowlands, the Mosquitia is Honduras's least-developed area.[1] Underpopulated and culturally distinct from the rest of the country, the area consists of inland savannah with swamps and mangrove near the coast.[1] During times of heavy rainfall, much of the savannah area is covered by shallow water, making transportation by means other than a shallow-draft boat almost impossible.[1]

More than 46 campesinos from the Aguán Valley, in the far north-east of Honduras, have either been killed or have disappeared since the 2009 coup.[3] In the 1970s, government policy encouraged agricultural cooperatives and collectives to establish themselves in the lightly populated area, but after 1992 government policy favored privatization.[3] One of the biggest beneficiaries of the new policy and one of the richest men in Honduras,[4] Miguel Facussé, owned some 22,000 acres (8,900 ha) in the lower Aguán, which he planted in African palms for his palm oil venture.

Pacific lowlands

[edit]The smallest geographic region of Honduras, the Pacific lowlands, is a strip of land averaging twenty-five km wide (16 mi) on the north shore of the Gulf of Fonseca.[1] The land is flat, becoming swampy near the shores of the gulf, and is composed mostly of alluvial soils washed down from the mountains.[1] The gulf is shallow and the water rich in fish and mollusks.[1] Mangroves along the shore make shrimp and shellfish particularly abundant by providing safe and abundant breeding areas amid their extensive networks of underwater roots.[1]

Several islands in the gulf fall under Honduras's jurisdiction.[1] The two largest, Zacate Grande and El Tigre, are eroded volcanoes, part of the chain of volcanoes that extends along the Pacific coast of Central America.[1] Both islands have volcanic cones more than 700 m (2,300 ft) in elevation that serve as landmarks for vessels entering Honduras's Pacific.[1]

Islands

[edit]

Honduras controls a number of islands as part of its offshore territories.[1] In the Caribbean Sea, the islands of Roatán (Isla de Roatán), Utila, and Guanaja together form the Islas de la Bahía (Bay Islands), one of the eighteen departments into which Honduras is divided.[1] Roatán, the largest of the three islands, is 50 by 5 km (31.1 by 3.1 mi).[1] The Islas de la Bahía archipelago also has a number of smaller islands, among them the islets of Barbareta (Isla Barbareta), Santa Elena (Isla Santa Elena), and Morat (Isla Morat).[1]

Farther out in the Caribbean are the Islas Santanillas, formerly known as Swan Islands. A number of small islands and keys can be found nearby, among them Cayos Zapotillos and Cayos Cochinos.[1] In the Gulf of Fonseca, the main islands under Honduran control are El Tigre, Zacate Grande (Isla Zacate Grande), and Exposición (Isla Exposición).[1]

-

Beach at the village of Juan López

-

The Merendón range seen from the vantage point located above the "Olimpo merendónico" in San Pedro Sula

-

A river in Honduras

-

The Rio Guayape near Esquilinchuche, facing El Boqueron in the Sierra de Agalta

Climate

[edit]

Honduras has a tropical climate and temperate climate in the highlands.[5]

The climatic types of each of the three physiographic regions differ.[1] The Caribbean lowlands have a tropical wet climate with consistently high temperatures and humidity, and rainfall fairly evenly distributed throughout the year.[1] The Pacific lowlands have a tropical wet and dry climate with high temperatures but a distinct dry season from November through April.[1] The interior highlands also have a distinct dry season, but, as is characteristic of a tropical highland climate, temperatures in this region decrease as elevation increases.[1]

Unlike in more northerly latitudes, temperatures in the tropics vary primarily with elevation instead of with the season.[1] Land below 1,000 meters (3,281 ft) is commonly known as tierra caliente (hot land), between 1,000 and 2,000 m (3,281 and 6,562 ft) as tierra templada (temperate land), and above 2,000 m (6,562 ft) as tierra fría (cold land).[1] Both the Caribbean and Pacific lowlands are tierra caliente, with daytime highs averaging between 28 and 32 °C (82.4 and 89.6 °F) throughout the year.[1]

In the Pacific lowlands, April, the last month of the dry season, brings the warmest temperatures; the rainy season is slightly cooler, although higher humidity during the rainy season makes these months feel more uncomfortable.[1] In the Caribbean lowlands, the only relief from the year-round heat and humidity comes during December or January when an occasional strong cold front from the north (a norte) brings several days of strong northwest winds and slightly cooler temperatures.[1]

The interior highlands range from tierra templada to tierra fría. Tegucigalpa, in a sheltered valley and at an elevation of 1,000 m (3,281 ft), has a pleasant climate, with an average high temperature ranging from 30 °C (86 °F) in April, the warmest month, to 25 °C (77 °F) in January, the coolest.[1] Above 2,000 meters (6,562 ft), temperatures can fall to near freezing at night, and frost sometimes occurs.[1]

Rain falls year round in the Caribbean lowlands but is seasonal throughout the rest of the country. Amounts are copious along the north coast, especially in the Mosquitia, where the average rainfall is 2,400 millimeters (94.5 in).[1] Nearer San Pedro Sula, amounts are slightly less from November to April, but each month still has considerable precipitation.[1] The interior highlands and Pacific lowlands have a dry season, known locally as "summer," from November to April.[1] Almost all the rain in these regions falls during the "winter," from May to September.[1] Total yearly amounts depend on surrounding topography; Tegucigalpa, in a sheltered valley, averages only 1,000 mm (39.4 in) of precipitation.[1]

Hurricanes

[edit]

Honduras lies within the hurricane belt, and the Caribbean coast is particularly vulnerable to hurricanes or tropical storms that travel inland from the Caribbean.[1] Hurricane Francelia in 1969 and Tropical Storm Aletta in 1982 affected thousands of people and caused extensive damage to crops.[1] Hurricane Fifi in 1974 killed more than 8,000 and destroyed nearly the entire banana crop.[1]

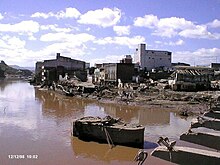

In 1998 Hurricane Mitch became the most deadly hurricane to strike the Western Hemisphere in the last two centuries.[6] This massive hurricane not only battered the Honduran coastline, but engulfed nearly the entire country with its powerful winds and torrential downpours.[7] Approximately 100,000 Hondurans were evacuated from the Caribbean coast.[7] Most of the Bay Islands had damage to their water facilities.[8]

The high rainfall caused many rivers in the country to overflow "to an unprecedented extent this century", as described by the United Nations.[9] Two earthflows caused significant damage near Tegucigalpa.[10] Hurricane Mitch wrought significant damage to Honduras, affecting nearly the entire population and causing damage in all 18 departments.[9] The United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean estimated that Mitch caused the worst floods of the 20th century in the country.[11] Throughout Central America, Mitch claimed in excess of 11,000 lives, with thousands of others missing.

Hurricanes occasionally form over the Pacific and move north to affect southern Honduras, but Pacific storms are generally less severe and their landfall rarer.[1]

On September 4, 2007, Hurricane Felix made landfall at Honduras and Nicaragua, as a Category 5 hurricane. In November 2008, Hurricane Paloma, along with the October 2008 Central America floods, left at least 60 people dead and more than 300,000 in need of assistance.[12]

Drought

[edit]Drought in Honduras has become a driver of emigration, causing poor crop yields for poor subsistence farmers, and has been a factor in the formation of migrant caravans to the United States.[13][14][15][16]

According to the FAO, migrants leaving central and western Honduras between 2014 and 2016 most frequently cited "no food" as their reason for leaving.[14]

Examples

[edit]| Climate data for Tegucigalpa (Tegucigalpa Airport) 1961–1990, extremes 1951–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.0 (91.4) |

34.5 (94.1) |

35.5 (95.9) |

36.6 (97.9) |

36.9 (98.4) |

34.5 (94.1) |

35.9 (96.6) |

36.9 (98.4) |

34.2 (93.6) |

34.8 (94.6) |

32.8 (91.0) |

31.4 (88.5) |

36.9 (98.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 25.7 (78.3) |

27.4 (81.3) |

29.5 (85.1) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30.2 (86.4) |

28.6 (83.5) |

27.8 (82.0) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.5 (83.3) |

27.3 (81.1) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.4 (77.7) |

27.9 (82.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 19.5 (67.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.6 (74.5) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.2 (72.0) |

21.5 (70.7) |

20.4 (68.7) |

19.7 (67.5) |

21.7 (71.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 14.3 (57.7) |

14.5 (58.1) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.1 (62.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.0 (64.4) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

16.3 (61.3) |

15.0 (59.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 4.5 (40.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

4.7 (40.5) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

12.6 (54.7) |

12.2 (54.0) |

11.0 (51.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.7 (45.9) |

6.8 (44.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 5.3 (0.21) |

4.7 (0.19) |

9.9 (0.39) |

42.9 (1.69) |

143.5 (5.65) |

158.7 (6.25) |

82.3 (3.24) |

88.5 (3.48) |

177.2 (6.98) |

108.9 (4.29) |

39.9 (1.57) |

9.9 (0.39) |

871.7 (34.32) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 13 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 73 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 66 | 62 | 60 | 67 | 75 | 74 | 73 | 76 | 78 | 77 | 75 | 71 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 220.8 | 229.4 | 268.5 | 242.8 | 216.3 | 171.7 | 192.5 | 204.8 | 183.4 | 200.4 | 199.2 | 212.2 | 2,542 |

| Source 1: NOAA[17] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (humidity, 1951–1993)[18] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[19] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for San Pedro Sula (La Mesa International Airport) 1961–1990, extremes 1944–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 37.2 (99.0) |

39.5 (103.1) |

42.8 (109.0) |

42.0 (107.6) |

42.0 (107.6) |

41.1 (106.0) |

38.0 (100.4) |

38.8 (101.8) |

39.2 (102.6) |

37.8 (100.0) |

37.5 (99.5) |

37.0 (98.6) |

42.8 (109.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 29.2 (84.6) |

30.4 (86.7) |

33.0 (91.4) |

34.0 (93.2) |

35.2 (95.4) |

34.3 (93.7) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.4 (92.1) |

33.5 (92.3) |

31.6 (88.9) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.2 (84.6) |

32.3 (90.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 23.5 (74.3) |

24.1 (75.4) |

25.8 (78.4) |

27.1 (80.8) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.1 (80.8) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.0 (78.8) |

24.7 (76.5) |

23.7 (74.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 19.8 (67.6) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.4 (70.5) |

22.5 (72.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

22.5 (72.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 12.8 (55.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

15.0 (59.0) |

20.2 (68.4) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

13.9 (57.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 72.0 (2.83) |

59.6 (2.35) |

32.0 (1.26) |

32.1 (1.26) |

62.9 (2.48) |

142.4 (5.61) |

110.2 (4.34) |

105.7 (4.16) |

151.7 (5.97) |

147.8 (5.82) |

135.3 (5.33) |

121.7 (4.79) |

1,173.4 (46.20) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 89 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84 | 81 | 77 | 75 | 74 | 76 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 81 | 83 | 85 | 80 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 186.0 | 178.0 | 238.7 | 222.0 | 220.1 | 201.0 | 210.8 | 198.4 | 183.0 | 198.4 | 156.0 | 155.0 | 2,347.4 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 6.0 | 6.3 | 7.7 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 6.7 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 6.4 |

| Source 1: NOAA[20] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun and humidity),[21] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[22] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for La Ceiba, Honduras (Golosón International Airport) 1970–1990, extremes 1965–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.8 (91.0) |

34.8 (94.6) |

35.4 (95.7) |

36.0 (96.8) |

38.0 (100.4) |

37.0 (98.6) |

35.7 (96.3) |

38.0 (100.4) |

36.0 (96.8) |

34.6 (94.3) |

33.6 (92.5) |

34.0 (93.2) |

38.0 (100.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 27.0 (80.6) |

27.6 (81.7) |

29.0 (84.2) |

30.1 (86.2) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.3 (88.3) |

30.8 (87.4) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.6 (87.1) |

29.5 (85.1) |

28.2 (82.8) |

27.3 (81.1) |

29.5 (85.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 23.8 (74.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.8 (80.2) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.2 (77.4) |

24.3 (75.7) |

26.2 (79.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 18.4 (65.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

19.5 (67.1) |

20.7 (69.3) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.6 (72.7) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.2 (68.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 13.2 (55.8) |

12.0 (53.6) |

11.5 (52.7) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

16.8 (62.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

12.1 (53.8) |

12.6 (54.7) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 305.2 (12.02) |

330.0 (12.99) |

225.2 (8.87) |

120.5 (4.74) |

76.9 (3.03) |

154.6 (6.09) |

174.9 (6.89) |

197.3 (7.77) |

203.3 (8.00) |

423.8 (16.69) |

539.6 (21.24) |

478.9 (18.85) |

3,230.2 (127.17) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 118 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81 | 83 | 82 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 78 | 79 | 84 | 80 | 82 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 170.5 | 192.1 | 217.0 | 234.0 | 213.9 | 192.0 | 201.5 | 217.0 | 174.0 | 151.9 | 144.0 | 151.9 | 2,259.8 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 5.5 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 7.8 | 6.9 | 6.4 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 5.8 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 6.2 |

| Source 1: NOAA[23] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun and humidity)[24] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[25] | |||||||||||||

Climate change

[edit]Hydrography

[edit]

Honduras is a water-rich country.[1] The most important river in Honduras is the Ulúa, which flows 400 km (250 mi) to the Caribbean through the economically important Valle de Sula.[1] Numerous other rivers drain the interior highlands and empty north into the Caribbean.[1] These other rivers are important, not as transportation routes, but because of the broad fertile valleys they have produced.[1] The Choluteca River runs south from Tegucigalpa through Choluteca and out at the Gulf of Fonseca.

Rivers also define about half of Honduras's international borders.[1] The Río Goascorán, flowing to the Gulf of Fonseca, and the Río Lempa define part of the border between El Salvador and Honduras.[1] The Coco River marks about half of the border between Nicaragua and Honduras.[1]

Despite an abundance of rivers, large bodies of water are rare.[1] Lago de Yojoa, located in the west-central part of the country, is the sole natural lake in Honduras.[1] This lake is twenty-two kilometers long and at its widest point measures fourteen kilometers.[1] Several large, brackish lagoons open onto the Caribbean in northeast Honduras.[1] These shallow bodies of water allow limited transportation to points along the coast.[1]

Statistics

[edit]- total area: 112,090 km2 (43,280 sq mi)

- land: 111,890 km2 (43,200 sq mi)

- water: 200 km2 (77 sq mi)

- total land boundaries: 1,575 km (979 mi)

- border countries:

- Guatemala 244 km (152 mi),

- El Salvador 391 km (243 mi),

- Nicaragua 940 km (580 mi)

- coastline: 832 km (517 mi)

- Maritime claims:

- territorial sea: 12 nmi (22.2 km; 13.8 mi)

- contiguous zone: 24 nmi (44.4 km; 27.6 mi)

- exclusive economic zone: 249,542 km2 (96,349 sq mi) and 200 nmi (370.4 km; 230.2 mi)

- continental shelf: natural extension of territory or to 200 nmi (370.4 km; 230.2 mi)

- Lowest point: Caribbean Sea 0 m

- Highest point: Cerro Las Minas 2,870 m (9,420 ft)

- land use:

- arable land: 9.12%

- permanent crops: 4.07%

- other: 86.82% (2012 est.)

- Irrigated land: 878.5 km (545.9 mi) (2007)

- Total renewable water resources: 95.93 km3 (23.01 cu mi) (2011)

- Freshwater withdrawal (domestic/industrial/agricultural):

- total: 2.12 km3 (0.51 cu mi) per year (16%/23%/61%)

- per capita: 295.6 m3 (10,440 cu ft) per year (2006)

Extreme Points

[edit]- Northernmost point: Great Swan Island, Swan Islands, Bay Islands Department

- Northernmost point (mainland): Puerto Castilla, Colón Department

- Southernmost point: Pacific coast border with Nicaragua, Choluteca Department

- Westernmost point: border with El Salvador and Guatemala, Ocotepeque Department

- Easternmost point: border with Nicaragua on Atlantic coast, Gracias a Dios Department

Natural resources

[edit]The natural resources include: timbers, gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, iron ore, antimony, coal, fish, and hydropower from the mountain rivers.

Natural hazards

[edit]Frequent mild earthquakes, damaging hurricanes, and floods along the Caribbean coast are examples of Honduran natural hazards.

Environmental issues

[edit]Deforestation poses a particular problem for Honduras; the goals of conserving endangered natural resources and promoting economic development has often been quite difficult to combine, which has resulted in conflicting policies that fail to protect forests. Honduras has suffered the greatest percentage loss of forest cover of any country in Latin America. The forests in Honduras are an important source of economic resources to finance government programs. The tropical forests in Honduras are diminishing rapidly due to poverty in the country. The majority of the population of Honduras see the forests as an obstacle to the expansion of ranching and agricultural activities, ignoring the significance that forests have for the society through protection of fauna, soils, recreation, purification of air, and the regulation of water sources. The urban population is also increasing rapidly over the years, which means that it has led to the clearing of land for farming and the farming of marginal soils in rural areas, as well as to uncontrolled development in the fringes of urban areas.

Illegal logging is also a major problem in Honduras. The majority of the production of timber in the country is illegal. According to the Center for International Policy and the Environmental Investigation Agency, the timber trade corruption involves politicians, timber companies, bureaucrats, mayors, and even the police. All of these factors contribute to deforestation and consequently to soil erosion. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization, Honduras lost 59,000 hectares of forest per year between 1990 and 2000.

Deforestation in regions dominated by tropical dry forests has advanced faster than regions dominated by other types of forests. Tropical dry forests have lower species richness compared to moist forests. However, tropical dry forests possess higher levels of endemic species, greater utility for humans, and also have a higher human population density. The effects of deforestation are more noticeable during tropical storms and hurricanes. In 1998, Hurricane Mitch killed thousands and also caused damage to the country. According to aerial surveys following the storm, mudslides were worse in deforested areas than forested areas. Many endangered species live in the forests of Honduras, and they may soon be extinct if deforestation continues. The climate has also changed because of the lack of trees in Honduras. This has caused the growing season for farmers to be shortened.

The ground in deforested areas is absorbing all the water as well. The largest source of freshwater in Honduras, Lake Yojoa, is on the verge of turning into a swamp. This is due to the high rate of pollution and logging as well. Lake Yojoa is also being polluted by heavy metals from local mining activities. Lake Yojoa is home to more than 400 species of birds, but the area surrounding the lake is suffering from deforestation and water pollution. However, not only Lake Yojoa is being polluted with heavy metals, nearby rivers and streams are also being polluted.[30][31][32][33][34]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Echeverri-Gent, Elisavinda (1995). Merrill, Tim (ed.). Honduras: a country study (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 66–74. ISBN 0-8444-0836-0. OCLC 31434665.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Echeverri-Gent, Elisavinda (1995). Merrill, Tim (ed.). Honduras: a country study (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 66–74. ISBN 0-8444-0836-0. OCLC 31434665.

- ^ Jacques, Jaime (2015-02-17). Moon El Salvador. Avalon Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61238-593-8.

- ^ a b Dana Frank (October 21, 2011). "WikiLeaks Honduras: US Linked to Brutal Businessman". The Nation.

- ^ Tracy Wilkinson (June 23, 2015). "Miguel Facusse dies at 90; colorful, ruthless Honduran tycoon".

- ^ Zúniga Andrade, Edgardo (1978). Las variantes del clima tropical lluvioso en Honduras y las características del clima en el Golfo de Fonseca y su litoral. Tegucigalpa, D.C., Honduras, C.A: Banco Central de Honduras.

- ^ Viets, Patricia (August 17, 2001). "NOAA delivers life-saving disaster-preparedness infrastructure and systems to Central America". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Juan Carlos Ulate (1998-10-29). "Hurricane Mitch at standstill, pounding Honduras". ReliefWeb. Reuters. Archived from the original on 2012-01-11. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- ^ Central America After Hurricane Mitch: The Challenge of Turning a Disaster into an Opportunity (Report). Inter-American Development Bank. 2000. Archived from the original on April 19, 2013. Retrieved 2013-05-22.

- ^ a b Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (1999-04-14). Honduras: Assessment of the Damage Caused by Hurricane Mitch, 1998 (PDF) (Report). United Nations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-19. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- ^ Edwin L. Harp; Mario Castañeda; Matthew D. Held (2002). Landslides Triggered By Hurricane Mitch In Tegucigalpa, Honduras (PDF) (Report). United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-05-19. Retrieved 2013-05-24.

- ^ Description of the Damage (PDF). Honduras: Assessment of the damage caused by hurricane Mitch, 1998. Implications for economic and social development and for the environment (Report). Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. April 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- ^ "Hondurans face many months of struggle after deadly floods, UN aid wing says". ReliefWeb. United Nations News Service. November 18, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Biggs, Marcia; Galiano-Rios, Julia (2019-04-02). "Climate change is killing crops in Honduras – and driving farmers north". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- ^ a b Leutert, Stephanie (November 6, 2018). "How climate change is affecting rural Honduras and pushing people north". Washington Post. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- ^ "Honduras: Climate Change Refugees – ARTE Reportage". ARTE in English. Archived from the original on 2021-03-01. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- ^ Markham, Lauren (2018-11-09). "The Caravan is a Climate Change Story". Pulitzer Center. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- ^ "Tegucigalpa Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Tegucigalpa (Int. Flugh.) / Honduras" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ "Station Tegucigalpa" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ "La Mesa Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ "Klimatafel von San Pedro Sula (La Mesa), Bez.Cortés / Honduras" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ "Station La Mesa" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ "La Ceiba Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ "Klimatafel von La Ceiba, Bez. Atlántida / Honduras" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ "Station Goloson" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ "Honduras | Global Climate Change". Climate Links, a Global Knowledge Portal for Climate and Development Practitioners. USAID. 2019. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- ^ CEPAL (Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe); MiAmbiente; Secretaría de Energía, Recursos Naturales, Ambiente y Minas - Honduras [in Spanish] (2016). "La Economía del Cambio Climático en Honduras. Mensajes Clave 2016" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 9.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "How climate change affects the Honduran economy". Energy Transition. 2019-03-07. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- ^ McMahan, Caleb D.; Fuentes-Montejo, César E.; Ginger, Luke; Carrasco, Juan Carlos; Chakrabarty, Prosanta; Matamoros, Wilfredo A. (2020-07-29). "Climate change models predict decreases in the range of a microendemic freshwater fish in Honduras". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 12693. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69579-7. ISSN 2045-2322.

- ^ Tucker, Christine (January–June 2005). "Comparative Spatial Analyses of Forest Conservation and Change in Honduras and Guatemala". Conservation & Society. 3 (1): 174–200.

- ^ Bass, Joby (October 2005). "Message in the Plaza: Landscape, Landscaping, and Forest Discourse in Honduras". Geographical Review. 95 (4): 556–577. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2005.tb00381.x. S2CID 161952241.

- ^ "Honduras: Environmental Profile". rainforests.mongabay.com.

- ^ Southworth, Jane (August 2001). "The Influence of Accessibility, Local Institutions, and Socioeconomic Factors on Forest Cover Change in the Mountains of Western Honduras" (PDF). Mountain Research and Development. 21 (3): 276–283. doi:10.1659/0276-4741(2001)021[0276:TIOALI]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 130401536.

- ^ Zúniga Andrade, Edgardo (1990). El clima e historia de ciudades y pueblos de Honduras. Tegucigalpa: Graficentro Editores.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.