Dravidian peoples

| Dravidians | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | South Asia and parts of Southeast Asia, mainly South India and Sri Lanka | ||

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families | ||

| Proto-language | Proto-Dravidian | ||

| Subdivisions |

| ||

| Language codes | |||

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | dra | ||

| Linguasphere | 49 = (phylozone) | ||

| Glottolog | drav1251 | ||

Distribution of subgroups of Dravidian languages:

| |||

Dravidian speakers in South Asia | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| approx. 250 million | |

| Languages | |

| Dravidian languages | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Hinduism, Dravidian folk religion and others: Jainism, Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, Judaism |

| Part of a series on |

| Dravidian culture and history |

|---|

|

The Dravidian peoples, Dravidian-speakers or Dravidians, are a collection of ethnolinguistic groups native to South Asia who speak Dravidian languages. There are around 250 million native speakers of Dravidian languages.[1] Dravidian speakers form the majority of the population of South India and are natively found in India, Pakistan, Afghanistan,[2] Bangladesh,[3] the Maldives, Nepal,[4] Bhutan[5] and Sri Lanka.[6] Dravidian peoples are also present in Singapore, Mauritius, Malaysia, France, South Africa, Myanmar, East Africa, the Caribbean, and the United Arab Emirates through recent migration.

Proto-Dravidian may have been spoken in the Indus civilization, suggesting a "tentative date of Proto-Dravidian around the early part of the third millennium BCE",[7] after which it branched into various Dravidian languages.[8] South Dravidian I (including pre-Tamil) and South Dravidian II (including pre-Telugu) split around the eleventh century BCE, with the other major branches splitting off at around the same time.[9]

The third century BCE onwards saw the development of many great empires in South India like Pandya, Chola, Chera, Pallava, Satavahana, Chalukya, Kakatiya and Rashtrakuta. Medieval South Indian guilds and trading organisations like the "Ayyavole of Karnataka and Manigramam" played an important role in the Southeast Asia trade,[10] and the cultural Indianisation of the region.

Dravidian visual art is dominated by stylised temple architecture in major centres, and the production of images on stone and bronze sculptures. The sculpture dating from the Chola period has become notable as a symbol of Hinduism. The Sri Ranganathaswamy Temple located in Indian state of Tamil Nadu is often considered as the largest functioning Hindu temple in the world. The temple is built in Dravidian style and occupies an area of 156 acres (631,000 m2).[11]

Etymology

The origin of the Sanskrit word drāviḍa is Tamil.[12] In Prakrit, words such as "Damela", "Dameda", "Dhamila" and "Damila", which later evolved from "Tamila", could have been used to denote an ethnic identity.[13] In the Sanskrit tradition, the word drāviḍa was also used to denote the geographical region of South India.[14] Epigraphic evidence of an ethnic group termed as such is found in ancient India and Sri Lanka where a number of inscriptions have come to light datable from the 2nd century BCE mentioning Damela or Dameda persons.[13] The Hathigumpha inscription of the Kalinga ruler Kharavela refers to a T(ra)mira samghata (Confederacy of Tamil rulers) dated to 150 BCE. It also mentions that the league of Tamil kingdoms had been in existence for 113 years by that time.[13] In Amaravati in present-day Andhra Pradesh there is an inscription referring to a Dhamila-vaniya (Tamil trader) datable to the 3rd century CE.[13] Another inscription of about the same time in Nagarjunakonda seems to refer to a Damila. A third inscription in Kanheri Caves refers to a Dhamila-gharini (Tamil house-holder). In the Buddhist Jataka story known as Akiti Jataka there is a mention to Damila-rattha (Tamil dynasty).

While the English word Dravidian was first employed by Robert Caldwell in his book of comparative Dravidian grammar based on the usage of the Sanskrit word drāviḍa in the work Tantravārttika by Kumārila Bhaṭṭa,[14] the word drāviḍa in Sanskrit has been historically used to denote geographical regions of southern India as whole. Some theories concern the direction of derivation between tamiḻ and drāviḍa; such linguists as Zvelebil assert that the direction is from tamiḻ to drāviḍa.[15]

Ethnic groups

The largest Dravidian ethnic groups are the Telugus from Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, the Tamils from Tamil Nadu, Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Singapore, the Kannadigas from Karnataka, the Malayalis from Kerala, and the Tulu people from Karnataka.

| Name | Subgroup | Population | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Badagas | South Dravidian | 133,500 (2011 census) | Badagas are found in Tamil Nadu. |

| Brahuis | North Dravidian | 700,000 (1996) | Brahuis are mostly found in the Balochistan region of Pakistan, with smaller numbers in southwestern Afghanistan. |

| Chenchus | South-Central Dravidian | 65,000 | Chenchus are found in Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Odisha. |

| Irula | South Dravidian | 203,382 (2011 census) | Irula are found in Tamil Nadu, Kerala |

| Giraavaru people | South Dravidian | 0 < 100 (Extinct) | Giraavaru people were found in Maldives. |

| Gondis | Central Dravidian | 13 million (approx.)[citation needed] | Gondi belong to the central Dravidian subgroup. They are spread over the states of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar and Odisha. A state named Gondwana was proposed to represent them in India. |

| Khonds | South-Central Dravidian | 1,627,486 (2011 census) | Khonds are found in Odisha. |

| Kannadigas | South Dravidian | 43.7 million[16] | Kannadigas are native to Karnataka in India but a considerable population is also found in Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Kerala. |

| Kodavas | South Dravidian | 160,000 (approx.)[citation needed] | Kodavas are native to the Kodagu district. |

| Koyas | Central Dravidian | found in Andhra Pradesh and Odisha | |

| Kurukh | North Dravidian | 3.6 million (approx.)[17] | Kurukh are spread over parts of the states of Chhatishgarh, Jharkhand and Odisha. Oraon people[clarification needed] of Bhutan and Nepal speak Kurukh, also Kurux, Oraon or Uranw, as their native language. |

| Kurumbar | South Dravidian | N/A | Kurumbar are found in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. |

| Malayalis | South Dravidian | 45 million[18][16] | Malayalis are native to Kerala and Lakshadweep, but are also found in Puducherry and parts of Tamil Nadu. They are also found in large numbers in Middle East countries, the Americas and Australia. |

| Paniya | South Dravidian | N/A | Paniya are found in Kerala and Tamil Nadu. |

| Tamils | South Dravidian | 78 million[19] | Tamils are native to Tamil Nadu, Puducherry and northern and eastern Sri Lanka, but are also found in parts of Kerala, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, although they have a large diaspora and are also widespread throughout many countries including South Africa, Singapore, the United States of America, Canada, Fiji, Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia, Philippines, Mauritius, European countries, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana and Malaysia, as are the other three major Dravidian languages.[20] |

| Telugus | Central Dravidian | 85.1 million[21] | Telugus are native to Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Yanam (Puducherry), but are also found in parts of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Orissa and Maharashtra. Further, they have a large diaspora and are also widespread throughout many countries including the United States of America, Canada, Australia and European countries. Telugu is the fastest growing language in the United States.[22] |

| Todas | South Dravidian | 2,002 (2011 census) | Todas are found in Tamil Nadu. |

| Tuluvas | South Dravidian | 2 million (approx.)[citation needed] | Tuluvas are found in coastal Karnataka and Northern Kerala (Kasaragodu district) in India. A state named Tulu Nadu was proposed to represent them in India. |

Language

The Dravidian language family is one of the oldest in the world. Six languages are currently recognized by India as Classical languages and four of them are Dravidian languages Tamil, Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam.

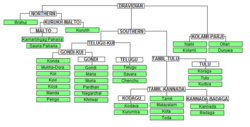

The most commonly spoken Dravidian languages are Telugu (తెలుగు), Tamil (தமிழ்), Kannada (ಕನ್ನಡ), Malayalam (മലയാളം), Brahui (براہوئی), Tulu (തുളു), Gondi and Coorg. There are three subgroups within the Dravidian language family: North Dravidian, Central Dravidian, and South Dravidian, matching for the most part the corresponding regions in the Indian subcontinent.

Dravidian grammatical impact on the structure and syntax of Indo-Aryan languages is considered far greater than the Indo-Aryan grammatical impact on Dravidian. Some linguists explain this anomaly by arguing that Middle Indo-Aryan and New Indo-Aryan were built on a Dravidian substratum.[23] There are also hundreds of Dravidian loanwords in Indo-Aryan languages, and vice versa.

According to David McAlpin and his Elamo-Dravidian hypothesis, the Dravidian languages were brought to India by immigration into India from Elam (not to be confused with Eelam), located in present-day southwestern Iran.[24][25] In the 1990s, Renfrew and Cavalli-Sforza have also argued that Proto-Dravidian was brought to India by farmers from the Iranian part of the Fertile Crescent,[26][27][28][note 1] but more recently Heggerty and Renfrew noted that "McAlpin's analysis of the language data, and thus his claims, remain far from orthodoxy", adding that Fuller finds no relation of Dravidian language with other languages, and thus assumes it to be native to India.[29] Renfrew and Bahn conclude that several scenarios are compatible with the data, and that "the linguistic jury is still very much out."[29]

As a proto-language, the Proto-Dravidian language is not itself attested in the historical record. Its modern conception is based solely on reconstruction. It is suggested that the language was spoken in the 4th millennium BCE, and started disintegrating into various branches around 3rd millennium BCE.[8] According to Krishnamurti, Proto-Dravidian may have been spoken in the Indus civilisation, suggesting a "tentative date of Proto-Dravidian around the early part of the third millennium."[7] Krishnamurti further states that South Dravidian I (including pre-Tamil) and South Dravidian II (including pre-Telugu) split around the eleventh century BCE, with the other major branches splitting off at around the same time.[9]

History

Origins

The origins of the Dravidians are a "very complex subject of research and debate".[30] They are regarded as indigenous to the Indian subcontinent,[31][32][33] but may have deeper pre-Neolithic roots from Western Asia, specifically from the Iranian plateau.[26][34][35][36][37] Their origins are often viewed as being connected with the Indus Valley civilisation,[30][37][38] hence people and language spread east and southwards after the demise of the Indus Valley Civilisation in the early second millennium BCE,[39][40] some propose not long before the arrival of Indo-Aryan speakers,[41] with whom they intensively interacted.[42] Though some scholars have argued that the Dravidian languages may have been brought to India by migrations from the Iranian plateau in the fourth or third millennium BCE[43][44] or even earlier,[45][46] reconstructed proto-Dravidian vocabulary suggests that the family is indigenous to India.[47][48]

Genetically, the ancient Indus Valley people were composed of a primarily Iranian hunter-gatherers (or farmers) ancestry, with varying degrees of ancestry from local hunter-gatherer groups. The modern-day Dravidian-speakers display a similar genetic makeup, but also carry a small portion of Western Steppe Herder ancestry and may also have additional contributions from local hunter-gatherer groups.[49][50][51]

Although in modern times speakers of various Dravidian languages have mainly occupied the southern portion of India, Dravidian speakers must have been widespread throughout the Indian subcontinent before the Indo-Aryan migration into the subcontinent.[52] According to Horen Tudu, "many academic researchers have attempted to connect the Dravidians with the remnants of the great Indus Valley civilisation, located in Northwestern India... but [i]t is mere speculation that the Dravidians are the ensuing post–Indus Valley settlement of refugees into South and Central India."[53] The most noteworthy scholar making such claims is Asko Parpola,[37] who did extensive research on the IVC-scripts.[37][38] The Brahui population of Balochistan in Pakistan has been taken by some as the linguistic equivalent of a relict population, perhaps indicating that Dravidian languages were formerly much more widespread and were supplanted by the incoming Indo-Aryan languages.[54]

Asko Parpola, who regards the Harappans to have been Dravidian, notes that Mehrgarh (7000–2500 BCE), to the west of the Indus River valley,[55] is a precursor of the Indus Valley Civilisation, whose inhabitants migrated into the Indus Valley and became the Indus Valley Civilisation.[36] It is one of the earliest sites with evidence of farming and herding in South Asia.[56][57] According to Lukacs and Hemphill, while there is a strong continuity between the neolithic and chalcolithic (Copper Age) cultures of Mehrgarh, dental evidence shows that the chalcolithic population did not descend from the neolithic population of Mehrgarh,[58] which "suggests moderate levels of gene flow".[58] They further noted that "the direct lineal descendants of the Neolithic inhabitants of Mehrgarh are to be found to the south and the east of Mehrgarh, in northwestern India and the western edge of the Deccan plateau", with neolithic Mehrgarh showing greater affinity with chalocolithic Inamgaon, south of Mehrgarh, than with chalcolithic Mehrgarh.[58]

Indus Valley Civilization

Dravidian identification

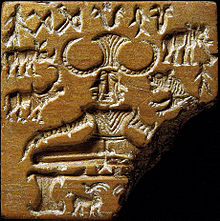

The Indus Valley civilisation (2,600–1,900 BCE) located in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent is sometimes identified as having been Dravidian.[59][60] Already in 1924, when announcing the discovery of the IVC, John Marshall stated that (one of) the language(s) may have been Dravidic.[61] Cultural and linguistic similarities have been cited by researchers Henry Heras, Kamil Zvelebil, Asko Parpola and Iravatham Mahadevan as being strong evidence for a proto-Dravidian origin of the ancient Indus Valley civilisation.[62][63] The discovery in Tamil Nadu of a late Neolithic (early 2nd millennium BCE, i.e. post-dating Harappan decline) stone celt allegedly marked with Indus signs has been considered by some to be significant for the Dravidian identification.[64][65]

Yuri Knorozov surmised that the symbols represent a logosyllabic script and suggested, based on computer analysis, an agglutinative Dravidian language as the most likely candidate for the underlying language.[66] Knorozov's suggestion was preceded by the work of Henry Heras, who suggested several readings of signs based on a proto-Dravidian assumption.[67]

Linguist Asko Parpola writes that the Indus script and Harappan language are "most likely to have belonged to the Dravidian family".[68] Parpola led a Finnish team in investigating the inscriptions using computer analysis. Based on a proto-Dravidian assumption, they proposed readings of many signs, some agreeing with the suggested readings of Heras and Knorozov (such as equating the "fish" sign with the Dravidian word for fish, "min") but disagreeing on several other readings. A comprehensive description of Parpola's work until 1994 is given in his book Deciphering the Indus Script.[69]

Decline, migration and Dravidianization

Paleoclimatologists believe the fall of the Indus Valley Civilisation and eastward migration during the late Harappan period was due to climate change in the region, with a 200-year long drought being the major factor.[70][71][72] The Indus Valley Civilisation seemed to slowly lose their urban cohesion, and their cities were gradually abandoned during the late Harappan period, followed by eastward migrations before the Indo-Aryan migration into the Indian subcontinent.[70]

The process of post-Harappan/Dravidian influences on southern India has tentatively been called "Dravidianization",[73] and is reflected in the post-Harappan mixture of IVC and Ancient Ancestral South Indian people.[74] Yet, according to Krishnamurti, Dravidian languages may have reached south India before Indo-Aryan migrations.[52]

Dravidian and Indo-Aryan interactions

Dravidian substrate

The Dravidian language influenced the Indo-Aryan languages. Dravidian languages show extensive lexical (vocabulary) borrowing, but only a few traits of structural (either phonological or grammatical) borrowing from Indo-Aryan, whereas Indo-Aryan shows more structural than lexical borrowings from the Dravidian languages.[52] Many of these features are already present in the oldest known Indo-Aryan language, the language of the Rigveda (c. 1500 BCE), which also includes over a dozen words borrowed from Dravidian. The linguistic evidence for Dravidian impact grows stronger as we move from the Samhitas down through the later Vedic works and into the classical post-Vedic literature.[75] This represents an early religious and cultural fusion[76][note 2] or synthesis[78] between ancient Dravidians and Indo-Aryans.[77][79][80][81]

According to Mallory there are an estimated thirty to forty Dravidian loanwords in Rig Veda.[82] Some of those for which Dravidian etymologies are certain include ಕುಲಾಯ kulāya "nest", ಕುಲ್ಫ kulpha "ankle", ದಂಡ daṇḍa "stick", ಕುಲ kūla "slope", ಬಿಲ bila "hollow", ಖಲ khala "threshing floor".[83] While J. Bloch and M. Witzel believe that the Indo-Aryans moved into an already Dravidian-speaking area after the oldest parts of the Rig Veda were already composed.[84]

According to Thomason and Kaufman, there is strong evidence that Dravidian influenced Indic through "shift", that is, native Dravidian speakers learning and adopting Indic languages.[85] According to Erdosy, the most plausible explanation for the presence of Dravidian structural features in Old Indo-Aryan is that the majority of early Old Indo-Aryan speakers had a Dravidian mother tongue which they gradually abandoned. Erdosy (1995:18) Even though the innovative traits in Indic could be explained by multiple internal explanations, early Dravidian influence is the only explanation that can account for all of the innovations at once. Early Dravidian influence accounts for several of the innovative traits in Indic better than any internal explanation that has been proposed.[86] According to Zvelebil, "several scholars have demonstrated that pre-Indo-Aryan and pre-Dravidian bilingualism in India provided conditions for the far-reaching influence of Dravidian on the Indo-Aryan tongues in the spheres of phonology, syntax and vocabulary."[87]

Sanskritization

With the rise of the Kuru Kingdom a process of Sanskritization started which influenced all of India, with the populations of the north of the Indian subcontinent predominantly speaking the Indo-Aryan languages.[88]

Dravidian kingdoms and empires

The third century BCE onwards saw the development of large Dravidian empires like Chola, Pandya, Rashtrakuta, Vijayanagara, Chalukyas Western Chalukya, and kingdoms like Chera, Chutu, Ay, Alupa, Pallava, Hoysala, Western Ganga, Eastern Ganga, Kadamba, Kalabhra, Andhra Ikshvaku, Vishnukundina, Eastern Chalukya, Sena, Kakatiya, Reddy, Mysore, Jaffna, Mysore, Travancore, Venad, Cochin, Cannanore, Calicut and the Nayakas.

Medieval trade and influence

Medieval Tamil guilds and trading organisations like the Ayyavole and Manigramam played an important role in the southeast Asia trade.[10] Traders and religious leaders travelled to southeast Asia and played an important role in the cultural Indianisation of the region. Locally developed scripts such as Grantha and Pallava script induced the development of many native scripts such as Khmer, Javanese Kawi, Baybayin, and Thai.

Around this time, Dravidians encountered Muslim traders, and the first Tamil Muslims and Sri Lankan Moors appeared.

European contact (1500 onward)

Portuguese explorers like Vasco de Gama were motivated to expand mainly for the spice markets of Calicut (today called Kozhikode) in modern-day Kerala. This led to the establishment of a series of Portuguese colonies along the western coasts of Karnataka and Kerala, including Mangalore. During this time Portuguese Jesuit priests also arrived and converted a small number of people in modern Kerala, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu to Catholicism, most notably the Paravars.

Dravidian culture

Religious belief

Ancient Dravidian religion constituted of an animistic and non-Vedic form of religion which may have influenced the Āgamas, Vedic and non-Vedic texts[89] which post-date the Vedic texts.[90] The Agamas are Tamil and Sanskrit scriptures chiefly constituting the methods of temple construction and creation of murti, worship means of deities, philosophical doctrines, meditative practices, attainment of sixfold desires and four kinds of yoga.[91] The worship of village deities, as well as sacred flora and fauna in Hinduism is recognised as a survival of the pre-Vedic Dravidian religion.[92] Hinduism can be regarded as a religious and cultural fusion[76][note 2] or synthesis[78] between ancient Dravidians and Indo-Aryans, and other local elements.[77][79][80][81]

Ancient Tamil grammatical works Tolkappiyam, the ten anthologies Pattuppāṭṭu, and the eight anthologies Eṭṭuttokai shed light on early ancient Dravidian religion. Murugan (also known as Seyyon) was glorified as the red god seated on the blue peacock, who is ever young and resplendent, as the favoured god of the Tamils.[93] Sivan was also seen as the supreme God.[93] Early iconography of Murugan[94] and Sivan[95][96][97] and their association with native flora and fauna goes back to the Indus Valley Civilisation.[98][99] The Sangam landscape was classified into five categories, thinais, based on the mood, the season and the land. Tolkappiyam mentions that each of these thinai had an associated deity such as Seyyon in Kurinji (hills), Thirumaal in Mullai (forests), and Kotravai in Marutham (plains), and Wanji-ko in the Neithal (coasts and seas). Other gods mentioned were Mayyon and Vaali, now identified with Krishna and Balarama, who are all major deities in Hinduism today. This represents an early religious and cultural fusion[76][note 2] or synthesis[78] between ancient Dravidians and Indo-Aryans, which became more evident over time with sacred iconography, traditions, philosophy, flora and fauna that went on to influence and shape Indian civilisation.[79][77][80][81]

Throughout Tamilakam, a king was considered to be divine by nature and possessed religious significance.[100] The king was 'the representative of God on earth' and lived in a "koyil", which means the "residence of a god". The Modern Tamil word for temple is koil (Tamil: கோயில்). Ritual worship was also given to kings.[101][102] Modern words for god like "kō" (Tamil: கோ "king"), "iṟai" (இறை "emperor") and "āṇḍavar" (ஆண்டவன் "conqueror") now primarily refer to gods. These elements were incorporated later into Hinduism like the legendary marriage of Shiva to Queen Mīnātchi who ruled Madurai or Wanji-ko, a god who later merged into Indra.[103] Tolkappiyar refers to the Three Crowned Kings as the "Three Glorified by Heaven", (Tamil: வாண்புகழ் மூவர், Vāṉpukaḻ Mūvar).[104] In Dravidian-speaking South India, the concept of divine kingship led to the assumption of major roles by state and temple.[105]

The cult of the mother goddess is treated as an indication of a society which venerated femininity. This mother goddess was conceived as a virgin, one who has given birth to all and one, and were typically associated with Shaktism.[106] The temples of the Sangam days, mainly of Madurai, seem to have had priestesses to the deity, which also appears predominantly as a goddess.[107] In the Sangam literature, there is an elaborate description of the rites performed by the Kurava priestess in the shrine Palamutircholai.[108]

Among the early Dravidians, the practice of erecting memorial stones, Natukal and Viragal, had appeared, and it continued for quite a long time after the Sangam age, down to about the 16th century.[109] It was customary for people who sought victory in war to worship these hero stones to bless them with victory.[110]

Architecture and visual art

Mayamata and Manasara shilpa texts estimated to be in circulation by the 5th to 7th century AD, are guidebooks on the Dravidian style of Vastu Shastra design, construction, sculpture and joinery technique.[111][112] Isanasivagurudeva paddhati is another text from the 9th century describing the art of building in India in south and central India.[111][113] In north India, Brihat-samhita by Varāhamihira is the widely cited ancient Sanskrit manual from the 6th century describing the design and construction of Nagara-style Hindu temples.[114][115][116] Traditional Dravidian architecture and symbolism are also based on Agamas. The Agamas are non-Vedic in origin[89] and have been dated either as post-Vedic texts[90] or as pre-Vedic compositions.[117] The Agamas are a collection of Tamil and Sanskrit scriptures chiefly constituting the methods of temple construction and creation of murti, worship means of deities, philosophical doctrines, meditative practices, attainment of sixfold desires and four kinds of yoga.[91]

Chola-style temples consist almost invariably of the three following parts, arranged in differing manners, but differing in themselves only according to the age in which they were executed:[118]

- The porches or Mantapas, which always cover and precede the door leading to the cell.

- Gate-pyramids, Gopuras, which are the principal features in the quadrangular enclosures that surround the more notable temples. Gopuras are very common in Dravidian temples.

- Pillared halls (Chaultris or Chawadis) are used for many purposes and are the invariable accompaniments of these temples.

Besides these, a south Indian temple usually has a tank called the Kalyani or Pushkarni – to be used for sacred purposes or the convenience of the priests – dwellings for all the grades of the priesthood are attached to it, and other buildings for state or convenience.[118]

Theatre, dance and music

Literary evidence of traditional form of theatre, dance and music dates back to the 3rd century BCE.[119] Ancient literary works, such as the Cilappatikaram, describe a system of music.[119] The theatrical culture flourished during the early Sangam age. Theatre-dance traditions have a long and varied history whose origins can be traced back almost two millennia to dance-theatre forms like Kotukotti, Kaapaalam and Pandarangam, which are mentioned in an ancient anthology of poems entitled the Kaliththokai.[120] Dance forms such as Bharatanatyam are based on older temple dance forms known as Catir Kacceri, as practised by courtesans and a class of women known as Devadasis.[121]

Carnatic music originated in the Dravidian region. With the growing influence of Persian and Sufi music on Indian music, a clear distinction in style appeared from the 12th century onwards. Many literary works were composed in Carnatic style and it soon spread wide in the Dravidian regions. The most notable Carnatic musician is Purandara Dasa who lived in the court of Krishnadevaraya of the Vijayanagara empire. He formulated the basic structure of Carnatic music and is regarded as the Pitamaha (lit, "father" or the "grandfather") of Carnatic Music. Kanakadasa is another notable Carnatic musician who was Purandaradasa's contemporary.

Each of the major Dravidian languages has its own film industry like Kollywood (Tamil), Tollywood (Telugu), Sandalwood (Kannada), Mollywood (Malayalam). Kollywood and Tollywood produce most films in India.[122]

Clothing

Dravidian speakers in southern India wear varied traditional costumes depending on their region, largely influenced by local customs and traditions. The most traditional dress for Dravidian men is the lungi, or the more formal dhoti, called veshti in Tamil, panche in Kannada and Telugu, and mundu in Malayalam. The lungi consists of a colourful checked cotton cloth. Many times these lungis are tube-shaped and tied around the waist, and can be easily tied above the knees for more strenuous activities. The lungi is usually everyday dress, used for doing labour while dhoti is used for more formal occasions. Many villagers have only a lungi as their article of clothing. The dhoti is generally white in colour, and occasionally has a border of red, green or gold. Dhotis are usually made out of cotton for more everyday use, but the more expensive silk dhotis are used for special functions like festivals and weddings.

Traditional dress of Dravidian women is typical of most Indian women, that of the sari. This sari consists of a cloth wrapped around the waist and draped over the shoulder. Originally saris were worn bare, but during the Victorian era, women began wearing blouse (called a ravike) along with sari. In fact, until the late 19th century most Kerala women did not wear any upper garments, or were forced to by law, and in many villages, especially in tribal communities, the sari is worn without the blouse. Unlike Indo-Aryan speakers, most Dravidian women do not cover their head with the pallu except in areas of North Karnataka. Due to the complexity of draping the sari, younger girls start with a skirt called a pavada. When they get older, around the age when puberty begins, they transition to a langa voni or half-sari, which is composed of a skirt tied at the waist along with a cloth draped over a blouse. After adulthood girls begin using the sari. There are many different styles of sari draping varying across regions and communities. Examples are the Madisar, specific to Tamil Brahmin Community, and the Mundum Neriyathum.

Martial arts and sports

In Mahabharata, Bhishma claimed that southerners are skilled with sword-fighting in general and Sahadeva was chosen for the conquest of the southern kingdoms due to his swordsmanship.[123] In South India various types of martial arts are practised like Kalaripayattu and Silambam.

In ancient times there were ankams, public duels to the death, to solve disputes between opposing rulers.[124] Among some communities, young girls received preliminary training up until the onset of puberty.[124] In vadakkan pattukal ballads, at least a few women warriors continued to practice and achieved a high degree of expertise.[124]

Sports like kambala, jallikattu, kabaddi, vallam kali, lambs and tigers, and maramadi remain strong among Dravidian ethnic groups.

See also

- General

- Dravidian languages

- Dravidian University (dedicated to research and learning of Dravidian languages)

- Culture

- Dance forms of Andhra Pradesh

- Culture of Telangana

- Arts of Kerala

- Dance forms of Tamil Nadu

- Folk arts of Karnataka

- Other

Notes

- ^ Derenko: "The spread of these new technologies has been associated with the dispersal of Dravidian and Indo-European languages in southern Asia. It is hypothesized that the proto-Elamo-Dravidian language, most likely originated in the Elam province in southwestern Iran, spread eastwards with the movement of farmers to the Indus Valley and the Indian sub-continent."[28]

Derenko refers to:

* Renfrew (1987), Archaeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins

* Renfrew (1996), Language families and the spread of farming. In: Harris DR, editor, The origins and spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia, pp. 70–92

* Cavalli-Sforza, Menozzi, Piazza (1994), The History and Geography of Human Genes. - ^ a b c Lockard: "The encounters that resulted from Aryan migration brought together several very different peoples and cultures, reconfiguring Indian society. Over many centuries a fusion of Aryan and Dravidian occurred, a complex process that historians have labeled the Indo-Aryan synthesis."[76] Lockard: "Hinduism can be seen historically as a synthesis of Aryan beliefs with Harappan and other Dravidian traditions that developed over many centuries."[77]

References

- ^ Steever, S.B., ed. (2019). The Dravidian languages (2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 1. doi:10.4324/9781315722580. ISBN 9781315722580. S2CID 261720917.

- ^ Louis, Rosenblatt; Steever, Sanford B. (15 April 2015). The Dravidian Languages. Routledge. p. 388. ISBN 978-1-136-91164-4. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ Razaul Karim Faquire (2010). "Language situation in Bangladesh". The Dhaka University Studies. 67 (2): 7. ISSN 1562-7195. OCLC 11674036.

- ^ "Dhangar Oraon in Nepal".

Dhangar Oraon people of Nepal speak Kurukh, also Kurux, Oraon or Uranw, as their native language. Which is a Dravidian language

- ^ "ORAON OF BHUTAN".

Oraon people of Bhutan speak Kurukh as their native language. Which is a Dravidian language

- ^ Swan, Michael; Smith, Bernard (26 April 2001). Learner English: A Teacher's Guide to Interference and Other Problems. Cambridge University Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-521-77939-5. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ a b Krishnamurti 2003, p. 501.

- ^ a b History and Archaeology, Volume 1, Issues 1–2 p.234, Department of Ancient History, Culture, and Archaeology, University of Allahabad

- ^ a b Krishnamurti 2003, p. 501–502.

- ^ a b Angela Schottenhammer, The Emporium of the World: Maritime Quanzhou, 1000–1400, p.293

- ^ "Tiruvarangam Divya Desam".

- ^ Shulman, David. Tamil. Harvard University Press.

- ^ a b c d Indrapala, K The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, pp.155–156

- ^ a b Zvelebil 1990, p. xx

- ^ Zvelebil 1990, p. xxi

- ^ a b "Census 2011: Languages by state". Censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "A-11 Individual Scheduled Tribe Primary Census Abstract Data and its Appendix". censusindia.gov.in. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Todd M.; Grim, Brian J. (2013). "Global Religious Populations, 1910–2010" (PDF). The World's Religions in Figures: An Introduction to International Religious Demography. John Wiley & Sons. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "World Tamil Population". Tamilo.com. August 2008. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ Sivasupramaniam, V. "History of the Tamil Diaspora". Murugan.org.

- ^ "Telugu People around the world". Friends of Telugu. Archived from the original on 25 February 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Do you speak Telugu? Welcome to America". BBC News. 21 October 2018.

- ^ Krishnamurti 2003, pp. 40–1

- ^ Kumar, Dhavendra (2004). Genetic Disorders of the Indian Subcontinent. Springer. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4020-1215-0. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

... The analysis of two Y chromosome variants, Hgr9 and Hgr3 provides interesting data (Quintan-Murci et al., 2001). Microsatellite variation of Hgr9 among Iranians, Pakistanis and Indians indicate an expansion of populations to around 9000 YBP in Iran and then to 6,000 YBP in India. This migration originated in what was historically termed Elam in south-west Iran to the Indus valley, and may have been associated with the spread of Dravidian languages from south-west Iran (Quintan-Murci et al., 2001). ...

- ^ David McAlpin, "Toward Proto-Elamo-Dravidian", Language vol. 50 no. 1 (1974); David McAlpin: "Elamite and Dravidian, Further Evidence of Relationships", Current Anthropology vol. 16 no. 1 (1975); David McAlpin: "Linguistic prehistory: the Dravidian situation", in Madhav M. Deshpande and Peter Edwin Hook: Aryan and Non-Aryan in India, Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (1979); David McAlpin, "Proto-Elamo-Dravidian: The Evidence and its Implications", Transactions of the American Philosophical Society vol. 71 pt. 3, (1981)

- ^ a b Cavalli-Sforza, Menozzi & Piazza 1994, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Namita Mukherjee; Almut Nebel; Ariella Oppenheim; Partha P. Majumder (December 2001), "High-resolution analysis of Y-chromosomal polymorphisms reveals signatures of population movements from central and western Asia into India", Journal of Genetics, 80 (3): 125–35, doi:10.1007/BF02717908, PMID 11988631, S2CID 13267463,

... More recently, about 15,000–10,000 years before present (ybp), when agriculture developed in the Fertile Crescent region that extends from Israel through northern Syria to western Iran, there was another eastward wave of human migration (Cavalli-Sforza et al., 1994; Renfrew 1987), a part of which also appears to have entered India. This wave has been postulated to have brought the Dravidian languages into India (Renfrew 1987). Subsequently, the Indo-European (Aryan) language family was introduced into India about 4,000 ybp ...

- ^ a b Derenko 2013.

- ^ a b Heggarty, Paul; Renfrew, Collin (2014), "South and Island Southeast Asia; Languages", in Renfrew, Colin; Bahn, Paul (eds.), The Cambridge World Prehistory, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9781107647756

- ^ a b Tudu 2008, p. 400

- ^ Avari, Burjor (2007). Ancient India: A History of the Indian Sub-Continent from C. 7000 BC to AD 1200. Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-134-25162-9.

- ^ Masica, Colin P. (1989). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- ^ Kopstein, Jeffrey; Lichbach, Mark Irving (2005) [First published 2000]. Comparative Politics: Interests, Identities, and Institutions in a Changing Global Order (2nd ed.). Cambridge University. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-521-84316-4.

- ^ Kumar, Dhavendra (2004). Genetic Disorders of the Indian Subcontinent. Springer. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4020-1215-0. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

... The analysis of two Y chromosome variants, Hgr9 and Hgr3 provides interesting data (Quintan-Murci et al., 2001). Microsatellite variation of Hgr9 among Iranians, Pakistanis and Indians indicate an expansion of populations to around 9000 YBP in Iran and then to 6,000 YBP in India. This migration originated in what was historically termed Elam in south-west Iran to the Indus valley, and may have been associated with the spread of Dravidian languages from south-west Iran (Quintan-Murci et al., 2001). ...

- ^ Kivisild 1999, p. 1333.

- ^ a b Parpola 2015, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Samuel 2008, p. 54 note 15.

- ^ a b Parpola 2015.

- ^ Narasimhan et al. 2018, p. 15.

- ^ Marris, Emma (3 March 2014). "200-Year Drought Doomed Indus Valley Civilization". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2014.14800. S2CID 131063035 – via Scientific American.

- ^ Razab Khan, The Dravidianization of India

- ^ Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (8 July 2015). "Dravidian languages". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Tamil Literature Society (1963), Tamil Culture, vol. 10, Academy of Tamil Culture, archived from the original on 9 April 2023, retrieved 25 November 2008,

... together with the evidence of archaeology would seem to suggest that the original Dravidian-speakers entered India from Iran in the fourth millennium BC ...

- ^ Andronov (2003), p. 299.

- ^ Namita Mukherjee; Almut Nebel; Ariella Oppenheim; Partha P. Majumder (December 2001), "High-resolution analysis of Y-chromosomal polymorphisms reveals signatures of population movements from central Asia and West Asia into India", Journal of Genetics, 80 (3), Springer India: 125–35, doi:10.1007/BF02717908, PMID 11988631, S2CID 13267463,

... More recently, about 15,000–10,000 years before present (ybp), when agriculture developed in the Fertile Crescent region that extends from Israel through northern Syria to western Iran, there was another eastward wave of human migration (Cavalli-Sforza et al., 1994; Renfrew 1987), a part of which also appears to have entered India. This wave has been postulated to have brought the Dravidian languages into India (Renfrew 1987). Subsequently, the Indo-European (Aryan) language family was introduced into India about 4,000 ybp ...

- ^ Dhavendra Kumar (2004), Genetic Disorders of the Indian Subcontinent, Springer, ISBN 1-4020-1215-2, archived from the original on 9 April 2023, retrieved 25 November 2008,

... The analysis of two Y chromosome variants, Hgr9 and Hgr3 provides interesting data (Quintan-Murci et al., 2001). Microsatellite variation of Hgr9 among Iranians, Pakistanis and Indians indicate an expansion of populations to around 9000 YBP in Iran and then to 6,000 YBP in India. This migration originated in what was historically termed Elam in south-west Iran to the Indus valley, and may have been associated with the spread of Dravidian languages from south-west Iran (Quintan-Murci et al., 2001). ...

- ^ Krishnamurti (2003), p. 15.

- ^ Avari (2007), p. 13.

- ^ Reich et al. 2009.

- ^ Narasimhan et al. 2019.

- ^ Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; Patterson, Nick; Moorjani, Priya; Rohland, Nadin; Bernardos, Rebecca; Mallick, Swapan; Lazaridis, Iosif; Nakatsuka, Nathan; Olalde, Iñigo; Lipson, Mark; Kim, Alexander M.; Olivieri, Luca M.; Coppa, Alfredo; Vidale, Massimo; Mallory, James (6 September 2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457): eaat7487. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

- ^ a b c Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (8 July 2015). "Dravidian languages". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Tudu 2008, p. 400

- ^ Mallory 1989, p. 44: "There are still remnant northern Dravidian languages including Brahui ... The most obvious explanation of this situation is that the Dravidian languages once occupied nearly all of the Indian subcontinent and it is the intrusion of Indo-Aryans that engulfed them in northern India leaving but a few isolated enclaves. This is further supported by the fact that Dravidian loan words begin to appear in Sanskrit literature from its very beginning."

- ^ "Stone age man used dentist drill". 6 April 2006.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage. 2004. "Archaeological Site of Mehrgarh". UNESCO.

- ^ Hirst, K. Kris. 2005. "Mehrgarh" Archived 18 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Guide to Archaeology

- ^ a b c Coningham & Young 2015, p. 114.

- ^ Mahadevan, Iravatham (6 May 2006). "Stone celts in Harappa". Harappa. Archived from the original on 4 September 2006.

- ^ Ansumali Mukhopadhyay, Bahata (3 August 2021). "Ancestral Dravidian languages in Indus Civilization: ultraconserved Dravidian tooth-word reveals deep linguistic ancestry and supports genetics". Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 8 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1057/s41599-021-00868-w. ISSN 2662-9992. S2CID 257091003.

- ^ Saju, M. T. (5 October 2018). "Pot route could have linked Indus & Vaigai". The Times of India.

- ^ Rahman, Tariq. "Peoples and languages in pre-Islamic Indus valley". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

most scholars have taken the 'Dravidian hypothesis' seriously

- ^ Cole, Jennifer (2006). "The Sindhi language" (PDF). In Brown, K. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Vol. 11 (2nd ed.). Elsevier. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2007.

Harappan language ... prevailing theory indicates Dravidian origins

- ^ Subramanium 2006; see also "A Note on the Muruku Sign of the Indus Script in light of the Mayiladuthurai Stone Axe Discovery" Archived 4 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine by I. Mahadevan (2006)

- ^ Subramanian, T. S. (1 May 2006). "Significance of Mayiladuthurai find". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 April 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ^ Knorozov 1965, p. 117

- ^ Heras 1953, p. 138

- ^ Bryant, Edwin (2003). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-19-516947-8.

- ^ Parpola 1994

- ^ a b Marris, Emma (3 March 2014). "200-Year Drought Doomed Indus Valley Civilization". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2014.14800. S2CID 131063035 – via Scientific American.

- ^ Keys, David (2 March 2014). "How climate change ended world's first great civilisations". The Independent. London.

- ^ Sinha, Kounteya (28 February 2014). "Climate change caused Indus Valley civilization collapse". The Times of India.

- ^ Razab Khan, The Dravidianization of India

- ^ Narasimhan et al. 2018.

- ^ Krishnamurti 2003, p. 6

- ^ a b c d Lockard 2007, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d Lockard 2007, p. 52.

- ^ a b c Hiltebeitel 2007, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Tiwari 2002, p. v.

- ^ a b c Zimmer 1951, pp. 218–219.

- ^ a b c Larson 1995, p. 81.

- ^ Mallory, J. P.; Adams, D. Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 308. ISBN 9781884964985.

- ^ Zvelebil 1990, p. 81.

- ^ Bryant, Edwin (2001). "Linguistic Substrata in Sanskrit Texts". The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 76–107. ISBN 978-0-19-513777-4.

- ^ Thomason & Kaufman 1988.

- ^ Thomason & Kaufman 1988, pp. 141–144.

- ^ Dravidian languages – Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ Witzel 1995.

- ^ a b Mudumby Narasimhachary (Ed) (1976). Āgamaprāmāṇya of Yāmunācārya, Issue 160 of Gaekwad's Oriental Series. Oriental Institute, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda.

- ^ a b Tripath, S. M. (2001). Psycho-Religious Studies Of Man, Mind And Nature. Global Vision Publishing House. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-81-87746-04-1.

- ^ a b Grimes, John A. (1996). A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English (New and Revised ed.). State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-3068-2.

- ^ The Modern review: Volume 28; Volume 28. Prabasi Press Private, Ltd. 1920.

- ^ a b Sinha, Kanchan (1979). Kārttikeya in Indian art and literature. Delhi: Sundeep Prakashan. OCLC 644105825.

- ^ Mahadevan, Iravatham (2006). A Note on the Muruku Sign of the Indus Script in light of the Mayiladuthurai Stone Axe Discovery. harappa.com. Archived from the original on 4 September 2006.

- ^ Ranbir Vohra (2000). The Making of India: A Historical Survey. M.E. Sharpe. p. 15. ISBN 9780765607119.

- ^ Bongard-Levin, Grigorii Maksimovich (1985). Ancient Indian Civilization. Arnold-Heinemann. p. 45. OCLC 12667676.

- ^ Steven Rosen, Graham M. Schweig (2006). Essential Hinduism. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 45.

- ^ Basham 1967, p. 27

- ^ Frederick J. Simoons (1998). Plants of life, plants of death. p. 363.

- ^ Harman, William P. (1992). The sacred marriage of a Hindu goddess. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 6.

- ^ Anand, Mulk Raj (1980). Splendours of Tamil Nadu. Marg Publications. ISBN 9780391025240.

- ^ Chopra, Pran Nath (1979). History of South India. S. Chand.

- ^ Bate, Bernard (2009). Tamil oratory and the Dravidian aesthetic: democratic practice in south India. Columbia University Press.

- ^ Kiruṭṭin̲an̲, A. (2000). Tamil culture: religion, culture, and literature. Bharatiya Kala Prakashan. p. 17. OCLC 603890991.

- ^ Embree, Ainslie Thomas (1988). Encyclopedia of Asian history: Volume 1. Scribner. ISBN 9780684188980.

- ^ Thiruchandran, Selvy (1997). Ideology, caste, class, and gender. Vikas Pub. House.

- ^ Manickam, Valliappa Subramaniam (1968). A glimpse of Tamilology. Academy of Tamil Scholars of Tamil Nadu. p. 75.

- ^ Lal, Mohan (2006). The Encyclopaedia Of Indian Literature. Vol. 5. Sahitya Akademi. p. 4396. ISBN 978-8126012213.

- ^ Shashi, S.S. (1996). Encyclopaedia Indica: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh: Volume 100. Anmol Publications.

- ^ Subramanium, N. (1980). Śaṅgam polity: the administration and social life of the Śaṅgam Tamils. Ennes Publications.

- ^ a b Stella Kramrisch (1976), The Hindu Temple Volume 1 & 2, ISBN 81-208-0223-3

- ^ Tillotson, G. H. R. (1997). Svastika Mansion: A Silpa-Sastra in the 1930s. South Asian Studies, 13(1), pp 87–97

- ^ Sastri, Ganapati (1920). Īśānaśivagurudeva paddhati. Trivandrum Sanskrit Series. OCLC 71801033.

- ^ Meister, Michael W. (1983). "Geometry and Measure in Indian Temple Plans: Rectangular Temples". Artibus Asiae. 44 (4): 266–296. doi:10.2307/3249613. JSTOR 3249613.

- ^ Elgood, Heather (2000). Hinduism and the Religious Arts. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 121–125. ISBN 978-0304707393.

- ^ Kern, H., ed. (1865). The Brhat Sanhita of Varaha-mihara (PDF). Calcutta: The Asiatic Society of Bengal.

- ^ Nagalingam, Pathmarajah (2009). The Religion of the Agamas. Siddhanta Publications. [1]

- ^ a b Fergusson, James (1997) [1910]. History of Indian and Eastern Architecture (3rd ed.). New Delhi: Low Price Publications. p. 309.

- ^ a b Nijenhuis, Emmie te (1974), Indian Music: History and Structure, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-03978-0 at pp. 4–5

- ^ Vaittiyaliṅkan̲, Ce (1977). Fine Arts and Crafts in Pattu-p-pāṭṭu and Eṭṭu-t-tokai. Annamalai University. p. 162. OCLC 4804957.

- ^ Leslie, Julia. Roles and rituals for Hindu women, pp.149–152

- ^ "Tamil leads as India tops film production". The Times of India. 22 December 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Mahabharata Text".

- ^ a b c Zarrilli, Phillip B. (1998). When the Body Becomes All Eyes: Paradigms, Discourses and Practices of Power in Kalaripayattu, a South Indian Martial Art. Oxford University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-19-563940-7.

Sources

- Andronov, Mikhail Sergeevich (2003). A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Languages. Otto Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-04455-4.

- Basham, A.L. (1967). The Wonder That was India (3rd ed.). London: Sidgwick & Jackson. OCLC 459272.

- Basu, Analabha; Sarkar-Roya, Neeta; Majumder, Partha P. (9 February 2016), "Genomic reconstruction of the history of extant populations of India reveals five distinct ancestral components and a complex structure", PNAS, 113 (6): 1594–9, Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.1594B, doi:10.1073/pnas.1513197113, PMC 4760789, PMID 26811443

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca; Menozzi, Paolo; Piazza, Alberto (1994), The History and Geography of Human Genes, Princeton University Press

- Coningham, Robin; Young, Ruth (2015), The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE–200 CE, Cambridge University Press

- Derenko, Miroslava (2013), "Complete Mitochondrial DNA Diversity in Iranians", PLOS ONE, 8 (11): e80673, Bibcode:2013PLoSO...880673D, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080673, PMC 3828245, PMID 24244704

- Gallego Romero, Irene; et al. (2011), "Herders of Indian and European Cattle Share their Predominant Allele for Lactase Persistence", Molecular Biology and Evolution, 29 (1): 249–60, doi:10.1093/molbev/msr190, PMID 21836184

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (2007) [First published 1987]. "Hinduism". In Kitagawa, Joseph M. (ed.). The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7007-1762-0.

- Heras, Henry (1953). Studies in Proto-Indo-Mediterranean Culture. Bombay: Indian Historical Research Institute. OCLC 2799353.

- Kivisild; et al. (1999), "Deep common ancestry of Indian and western-Eurasian mitochondrial DNA lineages", Current Biology, 9 (22): 1331–1334, doi:10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80057-3, PMID 10574762, S2CID 2821966

- Knorozov, Yuri V. (1965). "Характеристика протоиндийского языка" [Characteristics of Proto-Indian language]. Predvaritel'noe soobshchenie ob issledovanii protoindiyskikh textov Предварительное сообщение об исследовании протоиндийских текстов [A Preliminary Report on the Study of Proto Texts] (in Russian). Moscow: Institute of Ethnography of the USSR.

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77111-5.

- Larson, Gerald (1995). India's Agony Over Religion. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2411-7.

- Lockard, Craig A. (2007). Societies, Networks, and Transitions. Vol. I: to 1500. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-618-38612-3.

- Mallory, J. P. (1989). In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology and Myth. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05052-1.

- Metspalu, Mait; Romero, Irene Gallego; Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Mallick, Chandana Basu; Hudjashov, Georgi; Nelis, Mari; Mägi, Reedik; Metspalu, Ene; Remm, Maido; Pitchappan, Ramasamy; Singh, Lalji; Thangaraj, Kumarasamy; Villems, Richard; Kivisild, Toomas (2011), "Shared and Unique Components of Human Population Structure and Genome-Wide Signals of Positive Selection in South Asia", The American Journal of Human Genetics, 89 (6): 731–744, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.010, ISSN 0002-9297, PMC 3234374, PMID 22152676

- Moorjani, P.; Thangaraj, K.; Patterson, N.; Lipson, M.; Loh, P.R.; Govindaraj, P.; Singh, L. (2013), "Genetic evidence for recent population mixture in India", The American Journal of Human Genetics, 93 (3): 422–438, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.07.006, PMC 3769933, PMID 23932107

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; Patterson, Nick; Moorjani, Priya; Lazaridis, Iosif; et al. (2018), "The Genomic Formation of South and Central Asia", bioRxiv 10.1101/292581

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; Patterson, Nick; Moorjani, Priya; Rohland, Nadin; et al. (6 September 2019). "The Formation of Human Populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457): eaat7487. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

- Palanichamy, Malliya Gounder (2015), "West Eurasian mtDNA lineages in India: an insight into the spread of the Dravidian language and the origins of the caste system", Human Genetics, 134 (6): 637–647, doi:10.1007/s00439-015-1547-4, PMID 25832481, S2CID 14202246

- Parpola, Asko (1994). Deciphering the Indus script. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43079-1.

- Parpola, Asko (2015), The Roots of Hinduism. The Early Arians and the Indus Civilization, Oxford University Press

- Reich, David; Thangaraj, Kumarasamy; Patterson, Nick; Price, Alkes L.; Singh, Lalji (2009), "Reconstructing Indian population history", Nature, 461 (7263): 489–494, Bibcode:2009Natur.461..489R, doi:10.1038/nature08365, ISSN 0028-0836, PMC 2842210, PMID 19779445

- Samuel, Geoffrey (2008), The Origins of Yoga and Tantra: Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge University Press

- Tiwari, Shiv Kumar (2002). Tribal Roots Of Hinduism. Sarup & Sons. ISBN 978-81-7625-299-7.

- Tudu, Horen (2008), "Dravidians", in Carole Elizabeth Boyce Davies (ed.), Encyclopedia of the African Diaspora: Origins, Experiences, and Culture [3 volumes]: Origins, Experiences, and Culture, ABC-CLIO, p. 400, ISBN 9781851097050

- Witzel, Michael (1995), "Early Sanskritization: Origin and Development of the Kuru state" (PDF), Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies, 1 (4): 1–26, archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2007

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1951). Philosophies of India. Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-691-01758-1.

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1990). Dravidian Linguistics: An Introduction. Pondicherry: Pondicherry Institute of Linguistics and Culture. ISBN 978-81-85452-01-2.

- Erdosy, George (1995). The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: Language, Material Culture and Ethnicity. Berlin: de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-014447-5.

- Indian Genome Variation Consortium (2008). "Genetic landscape of the people of India: A canvas for disease gene exploration". Journal of Genetics. 87 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1007/s12041-008-0002-x. PMID 18560169. S2CID 21473349.

- Thomason, Sarah Grey; Kaufman, Terrence (1988). Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05789-0.

External links

- Origins

- Akhilesh Pillalamarri, Where Did Indians Come from, part1, part 2, part 3

- Scroll.in, "Aryan migration: Everything you need to know about the new study on Indian genetics". 2 April 2018., on Narasimhan (2018)

- Language

- Bhadriraju Krishnamurti, Dravidian languages, Encyclopædia Britannica

- Dravidian language family is approximately 4,500 years old, Max-Planck-Gesellschaft