Space sexology

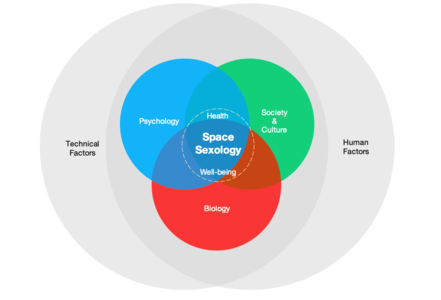

Space sexology has been defined as the "comprehensive scientific study of extraterrestrial intimacy and sexuality".[1][2][3] It aims to holistically understand intimacy and sexuality in space, including its risks, and potential benefits for the health and well-being of those who travel beyond our home planet.[1]

History

[edit]Spokespeople for space organizations, such as NASA, have historically gone on record expressing that they do not study sexuality in space.[4][5][6] In fact, Bill Jeffs, the spokesperson for NASA's Johnson Space Center, has stated that: "We don't study sexuality in space, and we don't have any studies ongoing with that. If that's [your] specific topic, there's nothing to discuss".[4] Some researchers and scientists have argued that decisions made by space organizations are often heavily influenced by the sociocultural norms of their benefactors.[1][7][8] As such, they posit that sexually conservative ideologies may hinder furthering the study of space sexology.[1] Given the persistent lack of research on human sexuality and intimacy in space, scientists and researchers have called for studies in this area for decades.[1][7][9][10][11][12][13][14]

In 1989, Roy Levin wrote the first paper exploring the potential effects of space travel on human sexuality and the human reproductive system, and called attention to the lack of research in this area.[14]

In 1998, Ray Noonan wrote the first philosophical inquiry on human intimacy and sexuality for extended spaceflights. In his doctoral thesis, Noonan discussed possible sexological challenges faced by astronauts on long-duration missions and related implications for mission success.[7] Expanding on his own work, Noonan proposed in 2001 that space agencies should collaborate with scientific communities to form programs to study sex in space.[13]

In 2005, Shimizu and colleagues echoed this belief, arguing that human sexuality research was crucial in order to successfully envision a future in space.[12]

In her 2016 book titled "Sex in Space", Laura Woodmansee explored questions relating to interstellar intercourse, from sexual mechanics, to conception, pregnancy, and birth in low gravity situations.[11] She further emphasized the need for extraterrestrial sex research.[11] That same year, Alexander Layendecker shed light on the absence of human sex research conducted by the NASA.[10] He further advocated for the development of an Astrosexological Research Institute.[10] Layendecker raised important questions regarding the possible effects of space conditions (e.g., exposure, radiation, microgravity, etc.) on phenomena such as conception, pregnancy, and child development.[10]

In 2018, Alexander Layendecker and Shawna Pandya co-wrote "Logistics of Reproduction in Space".[9] In it, they present the body of research that has been produced on topics of human sexuality, reproduction and development in space.[9] They also explored some of the logistical challenges associated with these topics.[9] However, they concluded that the current literature on such topics remains scarce, and that there is not enough data to assert whether conception, gestation, and development can safely (or successfully) occur in space.[9]

Most recently, in 2021, Dubé and colleagues highlighted the importance of considering space sexology as a scientific field and research program.[1] Noting a significant lack of research related to space intimacy and sexuality, their article titled "The Case for Space Sexology" explores the risks and benefits of studying these basic human needs in an extraterrestrial context.[1] They posit that the use of a biopsychosocial framework could expedite and improve research among space organizations while contributing to the health and well-being of future space inhabitants.[1] Since the publication, the authors have commented on the growth of support among the research community and space sector for the advancement of space sexology.[5] For example, Maria Santaguida, co-author of the article, stated in an interview with Mic that: "More and more researchers around the globe and people working in the space sector recognize that addressing human intimate and sexual needs in space is one of the keys to unlocking our long-term expansion into the universe".[5]

It has been argued that NASA's rigid stance on sexuality in space may be softening.[5] When asked to comment on Dubé and colleagues' "The Case for Space Sexology" by a MIC journalist, a NASA representative stated that "Should a future need for more in-depth study on reproductive health in space be identified, NASA would take the appropriate steps."[5] In contrast with NASA's historically blunt rejections of proposals regarding sex and space, this response has been interpreted as a signal of change – one which may open the door for future exploration of human sexuality in space.[5][4]

Anticipated risks and benefits of sexuality in space

[edit]Dubé et al. (2021) proposed that space organizations should embrace the discipline of space sexology to enhance the benefits and mitigate the risks of human sexuality and intimacy in space.[1] The researchers described risks associated with the physical and chemical properties of space environments, such as the effects of ionizing radiation and gravitational changes on fertility, conception, pregnancy and fetal/child development.[1] Other risks are related to the intimacy and needs of space-travelers, such as the limited privacy on spacecraft, hygienic concerns, long-term isolation and mental health repercussions arising from lack of sexual fulfilment.[1] Dubé and colleagues (2021) also expressed concern over the potential sexual violence and harassment as these acts have already occurred in space simulation contexts.[1][15][16] This concern was reiterated by Santaguida and colleagues (2022) who argued that it is “time to plan for #MeToo in space.”[17] For example, Judith Lapierre, co-author of the article, experienced sexual harassment on a 110-day experiment on a Mir Space Station replica.[16][15] Less than a month into the experiment, Lapierre was non-consensually grabbed and kissed by a Russian crew member who oversaw the mission.[18] She was also subjected to other forms of sexist behaviors by her male colleagues.[18][19][1] While discussing these events in another publication, Lapierre stated: "It is time, more than ever, to meet the real challenges of space exploration, with honesty, transparency, and by recognizing that Earth's unacceptable behaviors are also Space's unacceptable behaviors for a spacefaring civilization".[15]

Dubé and colleagues (2021) identified some of the benefits that could accompany studying sex in space.[1] Such benefits directly impact the health and well-being of astronauts, an idea supported by an extensive body of research conducted on the positive benefits of sex on both physiological and psychological aspects of human functioning.[1][20][21] Physiologically, sex can have a positive impact on stress levels, blood pressure, sleep, immune functioning and cardiovascular health.[1] Psychologically, sex is important in maintaining a positive self-esteem and body image, and masturbation (a practical and accessible practice) has been shown to be particularly healthy and important in relieving sexual tension and stress.[20][22][23][1]

Potential solutions to the challenges of space sexology

[edit]Despite intimacy and sexuality becoming increasingly recognized as a fundamental human right,[citation needed] space organizations have historically evaded sex-related research.[8][9]Researchers have speculated that these organizations tend to avoid controversies that could result in reduced funding.[1][9] Dubé et al. (2021) proposed that space organizations should be reminded of the risks of limiting sex and intimacy in space while highlighting the potential benefits of enabling them as a possible solution.[1] They argue that organizations are ultimately responsible for the health and well-being of their astronauts and as such, intimate and sexual needs ought not be overlooked.[1] To better meet the needs of their space travellers, they state that space organizations may want to adopt a progressive, sex-positive agenda that values sexual rights.[1] They suggested that emphasizing the importance of intimacy and sex in space could in turn help investors and the public view this discipline as valuable and necessary.[1]

Dubé and colleagues (2021) proposed that technological systems and guidelines enabling intimacy and sexuality in the limiting artificial ecosystems of space will need to be created.[1] They describe that these systems and guidelines will likely need to be designed to be both safe and hygienic, similar to the already established systems in place for other basic needs such as eating and grooming.[1] They also suggest that this challenge can be addressed by space organizations by considering the use of sexual technology adapted for space to meet the intimate needs of their astronauts, such as erotic stimuli, sex toys, and artificial erotic agents (e.g., virtual partners, erotic chatbots, and sex robots).[1]

Dubé and colleagues (2021) indicate that successfully researching space sexology will likely require cooperation and contributions from both space organizations and their astronauts.[1] They acknowledge that this may prove challenging, as conflicting sexual views between administrators and astronauts alike could complicate group cohesion.[1] To facilitate an inclusive understanding of the value of extraterrestrial sex and intimacy, Dubé and colleagues (2021) recommend that space organizations invest in training programs that encapsulate the complexity of human intimacy and sexuality.[1] Such programs could aim to foster sex-positive ethics among space organizations and their respective personnel.[1]

See also

[edit]- Sex in space

- Space tourism

- Space medicine

- Space colonization

- Space advocacy

- Effect of spaceflight on the human body

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Dubé, S.; Santaguida, M.; Anctil, D.; Giaccari, L.; Lapierre, J. (2021-12-08). "The Case for Space Sexology". The Journal of Sex Research. 60 (2): 165–176. doi:10.1080/00224499.2021.2012639. ISSN 0022-4499. PMID 34878963. S2CID 245006810.

- ^ Anctil, Dave; Lapierre, Judith; Giaccari, Lisa; Santaguida, Maria; Dubé, Simon. "Love and rockets: We need to figure out how to have sex in space for human survival and well-being". The Conversation. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- ^ "It's Time to Study Space Sexology". Discovery. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- ^ a b c Jeanna Bryner (2008-07-07). "For Better or Worse, Sex in Space Is Inevitable". Space.com. Retrieved 2022-05-23.

- ^ a b c d e f "Inside the push to study sex in space". Mic. Retrieved 2022-05-21.

- ^ Whitesides, Loretta Hidalgo. "Sex in Space, Why NASA Isn't Talking". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2022-05-23.

- ^ a b c Noonan, R. J. (1998). "A philosophical inquiry into the role of sexology in space life sciences research and human factors considerations for extended spaceflight". New York University. PhilPapers.

- ^ a b Roach, Mary (2010). Packing for Mars. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 236.

- ^ a b c d e f g Layendecker, Alexander B.; Pandya, Shawna (2018), Seedhouse, Erik; Shayler, David J (eds.), "Logistics of Reproduction in Space", Handbook of Life Support Systems for Spacecraft and Extraterrestrial Habitats, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–16, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-09575-2_211-1, ISBN 978-3-319-09575-2, S2CID 91780873, retrieved 2022-05-21

- ^ a b c d Layendecker, A, B. (2016). "Sex in outer space and the advent of astrosexology: A philosophical inquiry into the implications of human sexuality and reproductive development factors in seeding humanity's future throughout the cosmos and the argument for an Astrosexological Research Institute". The Institute for Advanced Study of Human Sexuality.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Woodmansee, Laura (2006). Sex in space. Collector's Guide Publishing, Inc.

- ^ a b Shimizu, Tsuyoshi; Netsu, Yahiro; Yoshikawa, Humihiko; Kamijo, Kaori; Hazama, Akihiro; Yamasaki, Masao (2005-10-17), "The importance of the study of sexuality for estab...", 56th International Astronautical Congress of the International Astronautical Federation, the International Academy of Astronautics, and the International Institute of Space Law, International Astronautical Congress (IAF), American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, doi:10.2514/6.iac-05-a1.p.01, retrieved 2022-05-21

- ^ a b Francoeur, Robert T; Noonan, Raymond J, eds. (2004). The Continuum Complete International Encyclopedia of Sexuality. Continuum. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199754700.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-975470-0.

- ^ a b Levin, R. J. (August 1989). "Effects of space travel on sexuality and the human reproductive system". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 42 (7): 378–382. ISSN 0007-084X. PMID 11540233.

- ^ a b c Lapierre, J (2007). "Operational, human factors and health research and issues for Mars 500 based on challenges of the Russian SFINCSS study in 1999: SFINCSS-99-00 Final Report, Simulation of flight of international crew on space station confinement study". European Space and Technology Research Center.

- ^ a b Lapierre, Judith; Bouchard, Stéphane; Martin, Thibault; Perreault, Michel (2009-06-01). "Transcultural group performance in extreme environment: Issues, concepts and emerging theory". Acta Astronautica. 64 (11): 1304–1313. Bibcode:2009AcAau..64.1304L. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2009.01.002. ISSN 0094-5765.

- ^ Santaguida, Maria; Lapierre, Judith; Dubé, Simon. "#MeToo in space: We must address the potential for sexual harassment and assault away from Earth". The Conversation. Retrieved 2022-10-13.

- ^ a b "Sexism In Space". www.vice.com. Retrieved 2022-05-23.

- ^ "Aspiring astronaut speaks out: harassment". CBC news. 2000.

- ^ a b Coleman, Eli (2003-01-23). "Masturbation as a Means of Achieving Sexual Health". Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality. 14 (2–3): 5–16. doi:10.1300/J056v14n02_02. ISSN 0890-7064. S2CID 143771742.

- ^ Brecher, Jeremy (1977). "Sex, Stress, and Health". International Journal of Health Services. 7 (1): 89–101. doi:10.2190/NBK8-VL8W-ADHV-JKTC. ISSN 0020-7314. PMID 832938. S2CID 19866617.

- ^ Brody, Stuart (2010-04-01). "The Relative Health Benefits of Different Sexual Activities". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 7 (4): 1336–1361. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01677.x. ISSN 1743-6095. PMID 20088868.

- ^ Gagnon, John H. (2005). "Solitary Sex: A Cultural History of Masturbation". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 34 (4): 471–473. doi:10.1007/s10508-005-4354-8. ISSN 0004-0002. S2CID 144131629.

External links

[edit]- Anctil, Dave; Lapierre, Judith; Giaccari, Lisa; Santaguida, Maria; Dubé, Simon (2022-08-22). "Love and rockets: We need to figure out how to have sex in space for human survival and well-being". The Conversation. Retrieved 2022-09-24.

- Bringing Sex to the Final Frontier: A Discussion on Space Sexology on YouTube

- Dubé, S.; Santaguida, M.; Anctil, D.; Giaccari, L.; Lapierre, J. (2021-12-08). "The Case for Space Sexology". The Journal of Sex Research. 60 (2). Informa UK Limited: 165–176. doi:10.1080/00224499.2021.2012639. ISSN 0022-4499. PMID 34878963. S2CID 245006810.

- Hay, Mark (2022-03-01). "Inside the push to study sex in space". Mic. Retrieved 2022-09-24.

- Ko, Mark (2021-10-15). "Can we masturbate in Space? The awkward reality of space tourism & how to overcome it". Tech Coffee House. Retrieved 2022-09-24.

- Mabe, Annalise (2022-09-23). "Sex in Space Will Look Like Nothing We've Ever Seen Before". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2022-09-24.