Science of reading

The science of reading (SOR) is the discipline that studies reading.[4] Foundational skills such as phonics, decoding, and phonemic awareness are considered to be important parts of the science of reading, but they are not the only ingredients. SOR includes any research and evidence about how humans learn to read, and how reading should be taught. This includes areas such as oral reading fluency, vocabulary, morphology, reading comprehension, text, spelling and pronunciation, thinking strategies, oral language proficiency, working memory training, and written language performance (e.g., cohesion, sentence combining/reducing).[5]

In addition, some educators feel that SOR should include digital literacy; background knowledge; content-rich instruction; infrastructural pillars (curriculum, reimagined teacher preparation, and leadership); adaptive teaching (recognizing the student's individual, culture, and linguistic strengths); bi-literacy development; equity, social justice and supporting underserved populations (e.g., students from low-income backgrounds).[4]

Some researchers suggest there is a need for more studies on the relationship between theory and practice. They say "We know more about the science of reading than about the science of teaching based on the science of reading", and "there are many layers between basic science findings and teacher implementation that must be traversed".[4]

In cognitive science, there is likely no area that has been more successful than the study of reading. Yet, in many countries reading levels are considered low. In the United States, the 2019 Nation's Report Card reported that 34% of grade-four public school students performed at or above the NAEP proficient level (solid academic performance) and 65% performed at or above the basic level (partial mastery of the proficient level skills).[6] As reported in the PIRLS study, the United States ranked 15th out of 50 countries, for reading comprehension levels of fourth-graders.[7] In addition, according to the 2011–2018 PIAAC study, out of 39 countries the United States ranked 19th for literacy levels of adults 16 to 65; and 16.9% of adults in the United States read at or below level one (out of five levels).[8][9]

Many researchers are concerned that low reading levels are due to how reading is taught. They point to three areas:

- Contemporary reading science has had very little impact on educational practice—mainly because of a "two-cultures problem separating science and education".

- Current teaching practice rests on outdated assumptions that make learning to read harder than it needs to be.

- Connecting evidence-based practice to educational practice would be beneficial, but is extremely difficult to achieve due to a lack of adequate training in the science of reading among many teachers.[10][11][12][13]

Simple view of reading

[edit]

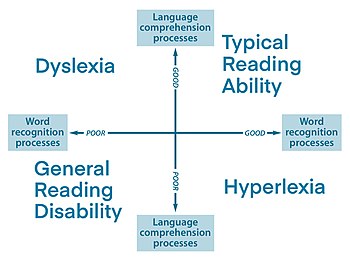

The simple view of reading is a scientific theory about reading comprehension.[14] According to the theory, to comprehend what they are reading students need both decoding skills and oral language (listening) comprehension ability. Neither is enough on their own. In other words, they need the ability to recognize and process (e.g., sound out) the text, and the ability to understand the language in which the text is written (i.e., vocabulary, grammar, and background knowledge). Students are not reading if they can decode words but do not understand their meaning. Similarly, students are not reading if they cannot decode words that they would ordinarily recognize and understand if they heard them spoken out loud.[15][16][17]

It is expressed in this equation: Decoding × Oral Language Comprehension = Reading Comprehension.[18]

As shown in the graphic, the Simple View of Reading proposes four broad categories of developing readers: typical readers; poor readers (general reading disability); dyslexics;[19] and hyperlexics.[20][21]

Scarborough's reading rope

[edit]Hollis Scarborough, the creator of the Reading Rope and senior scientist at Haskins Laboratories, is a leading researcher of early language development and its connection to later literacy.[22]

Scarborough published the Reading Rope infographics in 2001 using strands of rope to illustrate the many ingredients that are involved in becoming a skilled reader. The upper strands represent language comprehension and reinforce one another. The lower strands represent word recognition and work together as the reader becomes accurate, fluent, and automatic through practice. The upper and lower strands all weave together to produce a skilled reader.[23]

| Language-comprehension (Upper strands) |

|---|

| Background knowledge (facts, concepts, etc.) |

| Vocabulary (breadth, precision, links, etc.) |

| Language structures (syntax, semantics, etc.) |

| Verbal reasoning (inference, metaphor, etc.) |

| Literacy knowledge (print concepts, genres, etc.) |

| Word-recognition (Lower strands) |

| Phonological awareness (syllables, phonemes, etc.) |

| Decoding (alphabetic principle, spelling-sound correspondence) |

| Sight recognition (of familiar words) |

More recent research by Laurie E. Cutting and Hollis S. Scarborough has highlighted the importance of executive function processes (e.g. working memory, planning, organization, self-monitoring, and similar abilities) to reading comprehension.[24][25] Easy texts do not require many executive functions; however, more difficult text requires more "focus on the ideas". Reading comprehension strategies, such as summarizing, may help.

Active view of reading model

[edit]The active view of reading (AVR) model (May 7, 2021), Nell K. Duke and Kelly B. Cartwright,[26] offers an alternative to the simple view of reading (SVR), and a proposed update to Scarborough's reading rope (SRR). It reflects key insights from scientific research on reading that are not captured in the SVR and SRR. Although the AVR model has not been tested as a whole in research, "each element within the model has been tested in instructional research demonstrating positive, causal influences on reading comprehension".[27] This model is more complete than the simple view of reading and does a better job of accommodating some of the knowledge about reading developed over the past several decades. However, it does not explain how these variables fit together, how their relative importance changes with development, or many other issues relevant to reading instruction.[28]

The model lists contributors to reading (and potential causes of reading difficulty) within, across, and beyond word recognition and language comprehension; including the elements of self-regulation. This feature of the model reflects the research documenting that not all profiles of reading difficulty are explained by low word recognition and/or low language comprehension. A second feature of the model is that it shows how word recognition and language comprehension overlap, and identifies processes that "bridge" these constructs.

The following chart shows the ingredients in the authors' infographic. In addition, the authors point out that reading is also impacted by text, task, and sociocultural context.

| Active Self Regulation |

|---|

| Motivation and engagement |

| Executive function skills |

| Strategy use (related to word recognition, comprehension, vocabulary, etc.) |

| Word recognition (WR) |

| Phonological awareness (syllables, phonemes, etc.) |

| Alphabetic principle |

| Phonics knowledge |

| Decoding skills |

| Recognition of words at sight |

| Bridging processes (the overlapping of WR and LC) |

| Print concepts |

| Reading fluency |

| Vocabulary knowledge |

| Morphological awareness (the structure of words and parts of words such as stems, root words, prefixes, and suffixes) |

| Graphophonological-semantic cognitive flexibility (letter-sound-meaning flexibility) |

| Language comprehension (LC) |

| Cultural and other content knowledge |

| Reading-specific background knowledge (genre, text, etc.) |

| Verbal reasoning (inference, metaphor, etc.) |

| Language structure (syntax, semantics, etc.) |

| Theory of mind (the ability to attribute mental states to ourselves and others)[29] |

Automaticity

[edit]In the field of psychology, automaticity is the ability to do things without occupying the mind with the low-level details required, allowing it to become an automatic response pattern or a habit. When reading is automatic, precious working memory resources can be devoted to considering the meaning of a text, etc.

The unexpected finding from cognitive science is that practice does not make perfect. For a new skill to become automatic, sustained practice beyond the point of mastery is necessary.[30][31]

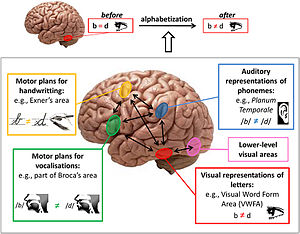

How the brain reads

[edit]Several researchers and neuroscientists have attempted to explain how the brain reads. They have written articles and books, and created websites and YouTube videos to help the average consumer.[32][33][34][35]

Neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene says that a few simple truths should be accepted by all, namely: a) all children have similar brains, are well tuned to systematic grapheme-phoneme correspondences, "and have everything to gain from phonics – the only method that will give them the freedom to read any text", b) classroom size is largely irrelevant if the proper teaching methods are used, c) it is essential to have standardized screening tests for dyslexia, followed by appropriate specialized training, and d) while decoding is essential, vocabulary enrichment is equally important.[36]

A study conducted at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in 2022 indicates that "greater left-brain asymmetry can predict both better and average performance on a foundational level of reading ability, depending on whether the analysis is conducted over the whole brain or in specific regions".[37][38] There have been correlations between specific brain regions in the left hemisphere of the cerebral cortex during different reading activities.[39]

Although it is not included in most meta-analytical studies, the sensorimotor cortex of the brain is the most active region of the brain during reading. This is often disregarded because it is associated solely with movement;[40] However, a 2014 fMRI study involving adults and children participants, where bodily movement was restricted, demonstrated strong evidence revealing that this region may be correlated with automatic word processing and decoding.[41] The results of this study found this portion of the brain to be highly active in persons who were learning/struggling to read (children, those diagnosed with dyslexia, and those new to the English language) and less active in fluent adult readers.[41]

The occipital and parietal lobes, or more specifically fusiform gyrus, include the brain's visual word form area (VWFA).[42] The VWFA is believed to be responsible for the brain's ability to read visually.[42] This area of the brain tends to be activated when words are presented orthographically, as found in a study in 2002 where participants were presented with word and non-word stimuli.[43] During presentation of word stimuli, this portion of the brain was extremely active; however, during presentation of stimuli that did not involve graphemes the brain was less active. Participants with dyslexia remained outliers, with this area of the brain being consistently underactive in both scenarios.[43]

The two major regions of the brain associated with phonological skills are the temporal-parietal region and the Perisylvian Region.[44] In an fMRI study conducted in 2001, participants were presented with written words, verbal frequency words, and verbal pseudo-words.[45] The dorsal (upper) portion of the temporal-parietal region was the most active during the pseudo-words and the ventral (lower) portion was more active during frequency words, except subjects diagnosed with dyslexia, who showed no impairment to their ventral region but under-activation in the dorsal portion.[45]

The Perisylvian Region, which is the portion of the brain believed to connect Broca's and Wernicke's area,[46] is another region that is highly active during phonological activities where participants are asked to verbalize known and unknown words.[47] Damage to this portion of this brain directly affects a person's ability to speak cohesively and with sense; furthermore, this portion of the brain activity remains consistent for both dyslexic and non-dyslexic readers.[48][49]

The inferior frontal region is a much more complex region of the brain, and its association with reading is not necessarily linear, for it is active in several reading-related activities.[50] Several studies have recorded its activity in association with comprehension and processing skills, as well as spelling and working memory.[51] Although the exact role of this portion of the brain is still debatable, several studies indicate that this area of the brain tends to be more active in readers who have been diagnosed with dyslexia and less active when treatment is successfully undergone.[52]

In addition to regions on the cortex, which is considered gray matter on fMRI's, there are several white matter fasciculus that are also active during different reading activities.[53] These three regions are what connect the three respected cortex regions as the brain reads, thus are responsible for the brain's cross-model integration involved in reading.[54] Three connective fasciculus that are prominently active during reading are the following: the left arcuate faciculus, the left inferior longitudinal faciculus, and the superior longitudinal fasciculus.[55] All three areas are found to be weaker in readers diagnosed with dyslexia.[53][54][55]

The cerebellum, which is not a part of the cerebral cortex, is also believed to play an important role in reading.[56] When the cerebellum is impaired, victims struggle with many executive functioning and organizational skills both inside and outside of their reading ability.[56] In a synthetic fMRI study, specific activities that displayed significant cerebellum involvement included automation, word accuracy, and reading speed.[57]

Eye movement and silent reading rate

[edit]Reading is an intensive process in which the eye quickly moves to assimilate the text – seeing just accurately enough to interpret groups of symbols.[58] It is necessary to understand visual perception and eye movement in reading to understand the reading process.

When reading, the eye moves continuously along a line of text but makes short rapid movements (saccades) intermingled with short stops (fixations). There is considerable variability in fixations (the point at which a saccade jumps to) and saccades between readers, and even for the same person reading a single passage of text. When reading, the eye has a perceptual span of about 20 slots. In the best-case scenario and reading English, when the eye is fixated on a letter, four to five letters to the right and three to four letters to the left can be clearly identified. Beyond that, only the general shape of some letters can be identified.[59]

The eye movements of deaf readers differ from those of readers who can hear, and skilled deaf readers have been shown to have shorter fixations and fewer refixations when reading.[60]

Research published in 2019 concluded that the silent reading rate of adults in English for non-fiction is in the range of 175 to 300 words per minute (wpm), and for fiction the range is 200 to 320 words per minute.[61][62]

Dual-route hypothesis to reading aloud

[edit]In the early 1970s, the dual-route hypothesis to reading aloud was proposed, according to which there are two separate mental mechanisms involved in reading aloud, with output from both contributing to the pronunciation of written words.[64][65][66] One mechanism is the lexical route whereby skilled readers can recognize a word as part of their sight vocabulary. The other is the nonlexical or sublexical route, in which the reader "sounds out" (decodes) written words.[66][67]

The production effect (reading out loud)

[edit]There is robust evidence that saying a word out loud makes it more memorable than simply reading it silently or hearing someone else say it. This is because self-reference and self-control over speaking produce more engagement with the words. The memory benefit of "hearing oneself" is referred to as the production effect.[68] This has implications for students such as those who are learning to read. The results of studies imply that oral production is beneficial because it entails two distinctive components: speaking (a motor act) and hearing oneself (the self-referential auditory input). It is also thought that the "optimal benefit would probably come from reading aloud from notes that the student took at the time of initial exposure to new information".[69][70]

Evidence-based reading instruction

[edit]Evidence-based reading instruction refers to practices having research evidence showing their success in improving reading achievement.[71][72][73][74][75] It is related to evidence-based education.

Several organizations report on research about reading instruction, for example:

- Best Evidence Encyclopedia (BEE) is a free website created by the Johns Hopkins University School of Education's Center for Data-Driven Reform in Education and is funded by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.[76] In 2021, BEE released a review of research on 51 different programs for struggling readers in elementary schools.[77] Many of the programs used phonics-based teaching and/or one or more other approaches. The conclusions of this report are shown in the section entitled Effectiveness of programs.

- Evidence for ESSA[78] began in 2017 and is produced by the Center for Research and Reform in Education (CRRE)[79] at Johns Hopkins University School of Education, Baltimore, MD.[80] It offers free up-to-date information on current PK–12 programs in reading, math, social-emotional learning, and attendance that meet the standards of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) (the United States K–12 public education policy signed by President Obama in 2015).[81]

- ProvenTutoring.org[82] is a non-profit organization, a separate subsidiary of the non-profit Success for All. It is a resource for school systems and educators interested in research-proven tutoring programs. It lists programs that deliver tutoring programs that are proven effective in rigorous research as defined in the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act. The Center for Research and Reform in Education at Johns Hopkins University provides the technical support to inform program selection.[83][84]

- What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) of Washington, DC,[85] was established in 2002 and evaluates numerous educational programs in twelve categories by the quality and quantity of the evidence and the effectiveness. It is operated by the federal National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), part of the Institute of Education Sciences (IES)[85] Individual studies are available that have been reviewed by WWC and categorized according to the evidence tiers of the United States Every student succeeds act (ESSA).[86]

- Intervention reports are provided for programs according to twelve topics (e.g. literacy, mathematics, science, behavior, etc.).[87]

- The British Educational Research Association (BERA)[88] claims to be the home of educational research in the United Kingdom.[89][90]

- Florida Center for Reading Research is a research center at Florida State University that explores all aspects of reading research. Its Resource Database allows you to search for information based on a variety of criteria.[91]

- Institute of Education Sciences (IES), Washington, DC,[92] is the statistics, research, and evaluation arm of the U.S. Department of Education. It funds independent education research, evaluation and statistics. It published a Synthesis of its Research on Early Intervention and Early Childhood Education in 2013.[93] Its publications and products can be searched by author, subject, etc.[94]

- National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER)[95] is a non-profit research and development organization based in Berkshire, England. It produces independent research and reports about issues across the education system, such as Using Evidence in the Classroom: What Works and Why.[96]

- Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted), in England, conducts research on schools, early education, social care, further education and skills.[97]

- The Ministry of Education, Ontario, Canada offers a site entitled What Works? Research Into Practice. It is a collection of research summaries of promising teaching practice written by experts at Ontario universities.[98]

- RAND Corporation, with offices throughout the world, funds research on early childhood, K–12, and higher education.[99]

- ResearchED,[100] a U.K. based non-profit since 2013 has organized education conferences around the world (e.g. Africa, Australia, Asia, Canada, the E.U., the Middle East, New Zealand, the U.K. and the U.S.) featuring researchers and educators to "promote collaboration between research-users and research-creators". It has been described as a "grass-roots teacher-led project that aims to make teachers research-literate and pseudo-science proof".[101]

Reading from paper vs. screens

[edit]A systematic review and meta‐analysis was conducted on the advantages of reading from paper vs. screens. It found no difference in reading times; however, reading from paper has a small advantage in reading performance and metacognition.[102] Other studies conclude that many children understand more from reading books vs. screens.[103][104]

Teacher training and legislation

[edit]According to some researchers, having a highly qualified teacher in every classroom is an educational necessity, and a 2023 study of 512 classroom teachers in 112 schools showed that teachers' knowledge of language and literacy reliably predicted students' reading foundational skills scores, but not reading comprehension scores.[105] Yet, some teachers, even after obtaining a master's degree in education, think they lack the necessary knowledge and skills to teach all students how to read.[106] A 2019 survey of K-2 and special education teachers found that only 11 percent said they felt "completely prepared" to teach early reading after finishing their preservice programs. And, a 2021 study found that most U.S. states do not measure teachers' knowledge of the 'science of reading'.[107] In addition, according to one study, as few as 2% of school districts use reading programs that follow the science of reading.[108][109] Mark Seidenberg, a neuroscientist, states that, with few exceptions, teachers are not taught to teach reading and "don't know what they don't know".[110]

A survey in the United States reported that 70% of teachers believe in a balanced literacy approach to teaching reading – however, balanced literacy "is not systematic, explicit instruction".[106] Teacher, researcher, and author, Louisa Moats,[111] in a video about teachers and science of reading, says that sometimes when teachers talk about their "philosophy" of teaching reading, she responds by saying, "But your 'philosophy' doesn't work".[112] She says this is evidenced by the fact that so many children are struggling with reading.[113] On another occasion, when asked about the most common questions teachers ask her, she replied, "over and over" they ask "why didn't anyone teach me this before?".[114] In an Education Week Research Center survey of more than 530 professors of reading instruction, only 22 percent said their philosophy of teaching early reading centered on explicit, systematic phonics with comprehension as a separate focus.[106]

As of October 2024, after Mississippi became the only state to improve reading results between 2017 and 2019,[115] 40 U.S. states and the District of Columbia have since passed laws or implemented new policies related to evidence-based reading instruction.[116] These requirements relate to six areas: teacher preparation; teacher certification or license renewal; professional development or coaching; assessment; material; and instruction or intervention. As a result, many schools are moving away from balanced literacy programs that encourage students to guess a word, and are introducing phonics where they learn to "decode" (sound out) words.[117] However, the adoption of these new requirements are by no means uniform. For example, only ten states have requirements in all six areas, and six have requirements in only one or two areas. Only twenty states have requirements related to pre-service teacher certification or license renewal. Thirty-eight states have requirements for professional development or coaching, and thirty-two require teachers to use specific instructional methods or interventions for struggling readers. Furthermore, fourteen states do not allow or require 3rd-grade retention for students who are behind in reading. Experts say it is uncertain whether these new initiatives will lead to real improvements in children's reading results because old practices prove hard to shake.[118][119]

As more state legislatures seek to pass science of reading legislation, some teachers' unions are mounting opposition, citing concerns about mandates that would limit teachers' professional autonomy in the classroom, uneven implementation, unreasonable timelines, and the amount of time and compensation teachers receive for additional training.[120] Some teachers' unions, in particular, have protested attempts to ban the three-cueing system that encourages students to guess at the pronunciation of words, using pictures, etc. (rather than to decode them). In April 2024, the California Teachers Union was successful in stopping a bill that would have required teachers to use the science of reading.[121]

Arkansas required every elementary and special education teacher to be proficient in the scientific research on reading by 2021; causing Amy Murdoch, an associate professor and the director of the reading science program at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati to say "We still have a long way to go – but I do see some hope".[106][122][123]

In 2021, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development of New Brunswick appears to be the first in Canada to revise its K-2 reading curriculum based on "research-based instructional practice". For example, it replaced the various cueing systems with "mastery in the consolidated alphabetic to skilled reader phase".[124][125] Although one document on the site, dated 1998, contains references to such practices as using "cueing systems" which is at odds with the department's current shift to using evidence-based practices.[126] The Minister of Education in Ontario, Canada followed by stating plans to revise the elementary language curriculum and the Grade 9 English course with "scientific, evidence-based approaches that emphasize direct, explicit and systematic instruction and removing references to unscientific discovery and inquiry-based learning, including the three-cueing system, by 2023."[127]

Some non-profit organizations, such as the Center for Development and Learning (Louisiana) and the Reading League (New York State), offer training programs for teachers to learn about the science of reading.[128][129][130][131] ResearchED, a U.K. based non-profit since 2013 has organized education conferences around the world featuring researchers and educators to promote collaboration between research-users and research-creators.[100]

Researcher and educator Timothy Shanahan acknowledges that comprehensive research does not always exist for specific aspects of reading instruction. However, "the lack of evidence doesn't mean something doesn't work, only that we don't know". He suggests that teachers make use of the research that is available in such places as Journal of Educational Psychology, Reading Research Quarterly, Reading & Writing Quarterly, Review of Educational Research, and Scientific Studies of Reading. If a practice lacks supporting evidence, it can be used with the understanding that it is based upon a claim, not science.[132]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Human language may have evolved to help our ancestors make tools, Science Magazine". January 13, 2015.

- ^ Stanislas Dehaene (2009). Reading in the brain. Penguin books. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-670-02110-9.

- ^ Mark Seidenberg (2017). Language at the speed of light. Basic Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-465-08065-6.

- ^ a b c "Making Sense of the Science of Reading". literacyworldwide.org.

- ^ "What Is the Science of Reading, Timothy Shanahan, Reading Rockets". 2019-05-29.

- ^ "NAEP 2019 grade 4 reading report" (PDF).

- ^ cite web|url=https://pirls2016.org/wp-content/uploads/structure/PIRLS/3.-achievement-in-purposes-and-comprehension-processes/3_1_achievement-in-reading-purposes.pdf%7Ctitle=PIRLSdate=2016

- ^ Skills Matter: Additional Results from the Survey of Adult Skills (PDF). OECD Skills Studies. OECD Skills Studies. 2019. p. 44. doi:10.1787/1f029d8f-en. ISBN 978-92-64-60466-7. S2CID 243226424.

- ^ Skills Matter: Additional Results from the Survey of Adult Skills (PDF). OECD Skills Studies. OECD Skills Studies. 2019. p. 44. doi:10.1787/1f029d8f-en. ISBN 978-92-64-60466-7. S2CID 243226424.

- ^ Seidenberg, M. S. (2013-08-26). "The Science of Reading and Its Educational Implications". Language Learning and Development. 9 (4): 331–360. doi:10.1080/15475441.2013.812017. PMC 4020782. PMID 24839408.

- ^ Stanislas Dehaene (2010). Reading in the brain. Penguin Books. pp. 218–234. ISBN 978-0-14-311805-3.

- ^ Kamil, Michael L.; Pearson, P. David; Moje, Elizabeth Birr; Afflerbach, Peter (2011). Handbook of Reading Research, Volume IV. Routledge. p. 630. ISBN 978-0-8058-5342-1.

- ^ Louisa C. Moats. "Teaching Reading Is Rocket Science, American Federation of Teachers, Washington, DC, USA, 2020" (PDF). p. 5.

- ^ Hoover, Wesley A.; Gough, Philip B. "Overview – The Cognitive Foundations of Learning to Read: A Framework". The Cognitive Foundations of Learning to Read: A Framework.

- ^ Castles, Anne; Rastle, Kathleen; Nation, Kate (11 June 2018). "Ending the Reading Wars: Reading Acquisition From Novice to Expert". Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 19 (1): 27. doi:10.1177/1529100618772271. PMID 29890888.

- ^ Refsnes, Hege. "Early Reading Intervention | Shanahan on Literacy". www.shanahanonliteracy.com.

- ^ Catts, Hugh W.; Hogan, Tiffany P.; Fey, Marc E. (18 August 2016). "Subgrouping Poor Readers on the Basis of Individual Differences in Reading-Related Abilities". Journal of Learning Disabilities. 36 (2): 151–164. doi:10.1177/002221940303600208. PMC 2848965. PMID 15493430.

- ^ Kendeou, Panayiota; Savage, Robert; Broek, Paul (June 2009). "Revisiting the simple view of reading". British Journal of Educational Psychology. 79 (2): 353–370. doi:10.1348/978185408X369020. PMID 19091164.

- ^ "Definition of 'Dyslexics'". Merriam-Webster. 14 September 2023.

- ^ "Medical Definition of 'Hyperlexia'". Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "Simple view of reading, Reading rockets". 6 June 2019.

- ^ "Hollis Scarborough | Haskins Laboratories". haskinslabs.org.

- ^ "Scarborough's Reading Rope: A Groundbreaking Infographic". The Examiner. 7 (2). April 2018.

- ^ Timothy Shanahan (2021-03-06). "Why Your Students May Not Be Learning to Comprehend".

- ^ Cutting, Laurie; Scarborough, Hollis (2012). "Multiple bases for comprehension difficulties: the potential of cognitive and neurobiological profiling for validation of subtypes and development of assessments, Reaching an understanding: Innovations in how we view reading assessment". pp. 101–116.

- ^ "Kelly B. Cartwright".

- ^ Duke, Nell K.; Cartwright, Kelly B. (2021-05-07). "The Science of Reading Progresses: Communicating Advances Beyond the Simple View of Reading". Reading Research Quarterly. 56. doi:10.1002/rrq.411.

- ^ Timothy Shanahan (2023-05-06). "What about the new research that says phonics instruction isn't very important".

- ^ "Theory of mind, Ruhl, C., Simply Psychology". 2020-08-07.

- ^ Samuels, S. Jay; Flor, Richard F. (1997). "The importance of automaticity for developing expertise in reading". Reading & Writing Quarterly, 13(2), 107–121. 13 (2): 107–121. doi:10.1080/1057356970130202.

- ^ Daniel T. Willingham (2004). "Ask the Cognitive Scientist: Practice Makes Perfect—But Only If You Practice Beyond the Point of Perfection".

- ^ "Youtube, How the Brain Learns to Read – Prof. Stanislas Dehaene, October 25, 2013". YouTube. 25 October 2013. Archived from the original on 2021-10-30.

- ^ Seidenberg, Mark (2017). Language at the speed of light. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-08065-6.

- ^ Dehaene, Stanislas (2010). Reading in the brain. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-311805-3.

- ^ Willingham, Daniel T. (2017). The reading mind. Jossey-Bass. ISBN 978-1-119-30137-0.

- ^ Stanislas Dehaene (2010). Reading in the brain. Penguin Books. pp. 327–328. ISBN 978-0-14-311805-3.

- ^ "How Left Brain Asymmetry Is Related to Reading Ability". Neuroscience News. Dyslexia Data Consortium. 5 April 2022. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ Mark A. Eckert; Kenneth I. Vaden Jr.; Federico Iuricich (5 April 2022). "Cortical asymmetries at different spatial hierarchies relate to phonological processing ability". PLOS Biology. 20 (4): e3001591. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3001591. PMC 8982829. PMID 35381012.

- ^ Price, Cathy J; Mechelli, Andrea (April 2005). "Reading and reading disturbance". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 15 (2): 231–238. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2005.03.003. PMID 15831408. S2CID 12138423.

- ^ Turkeltaub, Peter E.; Eden, Guinevere F.; Jones, Karen M.; Zeffiro, Thomas A. (July 2002). "Meta-Analysis of the Functional Neuroanatomy of Single-Word Reading: Method and Validation". NeuroImage. 16 (3): 765–780. doi:10.1006/nimg.2002.1131. PMID 12169260. S2CID 8122844.

- ^ a b Dekker, Tessa M.; Mareschal, Denis; Johnson, Mark H.; Sereno, Martin I. (December 2014). "Picturing words? Sensorimotor cortex activation for printed words in child and adult readers". Brain and Language. 139: 58–67. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2014.09.009. PMC 4271739. PMID 25463817.

- ^ a b McCandliss, Bruce D.; Cohen, Laurent; Dehaene, Stanislas (July 2003). "The visual word form area: expertise for reading in the fusiform gyrus". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 7 (7): 293–299. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(03)00134-7. PMID 12860187. S2CID 8534353.

- ^ a b Cohen, Laurent; Lehéricy, Stéphane; Chochon, Florence; Lemer, Cathy; Rivaud, Sophie; Dehaene, Stanislas (May 2002). "Language-specific tuning of visual cortex? Functional properties of the Visual Word Form Area". Brain. 125 (5): 1054–1069. doi:10.1093/brain/awf094. ISSN 1460-2156. PMID 11960895.

- ^ Turkeltaub, Peter E; Gareau, Lynn; Flowers, D Lynn; Zeffiro, Thomas A; Eden, Guinevere F (July 2003). "Development of neural mechanisms for reading". Nature Neuroscience. 6 (7): 767–773. doi:10.1038/nn1065. ISSN 1097-6256. PMID 12754516. S2CID 1256871.

- ^ a b Taylor, J. S. H.; Rastle, Kathleen; Davis, Matthew H. (2013). "Can cognitive models explain brain activation during word and pseudoword reading? A meta-analysis of 36 neuroimaging studies". Psychological Bulletin. 139 (4): 766–791. doi:10.1037/a0030266. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 23046391.

- ^ Catani, Marco; Jones, Derek K.; ffytche, Dominic H. (January 2005). "Perisylvian language networks of the human brain". Annals of Neurology. 57 (1): 8–16. doi:10.1002/ana.20319. ISSN 0364-5134. PMID 15597383. S2CID 17743067.

- ^ Rutten, Geert-Jan (2017). The Broca-Wernicke Doctrine. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-54633-9. ISBN 978-3-319-54632-2. S2CID 12820073.

- ^ Casanova-Robin, Hélène (2002). "L'Actéon ovidien: un voyeur sans regard [L'art du paradoxe et de l'ellipse dans la poétique d'Ovide: de l'omission du regard à la perte de la parole]". Bulletin de l'Association Guillaume Budé: Lettres d'humanité. 61 (4): 36–48. doi:10.3406/bude.2002.2476. ISSN 1247-6862.

- ^ Wernicke, Carl (1974). "Der aphasische Symptomenkomplex". Der aphasische Symptomencomplex (in German). Springer. pp. 1–70. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-65950-8_1. ISBN 978-3-642-65950-8.

- ^ Aparicio, Mario; Gounot, Daniel; Demont, Elisabeth; Metz-Lutz, Marie-Noëlle (April 2007). "Phonological processing in relation to reading: An fMRI study in deaf readers". NeuroImage. 35 (3): 1303–1316. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.12.046. PMID 17329129. S2CID 20053235.

- ^ Purcell, Jeremy J.; Napoliello, Eileen M.; Eden, Guinevere F. (March 2011). "A combined fMRI study of typed spelling and reading". NeuroImage. 55 (2): 750–762. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.042. PMC 3035733. PMID 21109009.

- ^ Hoeft, Fumiko; Meyler, Ann; Hernandez, Arvel; Juel, Connie; Taylor-Hill, Heather; Martindale, Jennifer L.; McMillon, Glenn; Kolchugina, Galena; Black, Jessica M.; Faizi, Afrooz; Deutsch, Gayle K.; Siok, Wai Ting; Reiss, Allan L.; Whitfield-Gabrieli, Susan; Gabrieli, John D. E. (2007). "Functional and morphometric brain dissociation between dyslexia and reading ability". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (10): 4234–4239. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.4234H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0609399104. PMC 1820738. PMID 17360506.

- ^ a b Price, Cathy J. (August 2012). "A review and synthesis of the first 20years of PET and fMRI studies of heard speech, spoken language and reading". NeuroImage. 62 (2): 816–847. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.062. ISSN 1053-8119. PMC 3398395. PMID 22584224.

- ^ a b D'Mello, Anila M.; Gabrieli, John D. E. (2018-10-24). "Cognitive Neuroscience of Dyslexia". Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 49 (4): 798–809. doi:10.1044/2018_lshss-dyslc-18-0020. ISSN 0161-1461. PMID 30458541. S2CID 53943474.

- ^ a b Perkins, Kyle; Zhang, Lawrence Jun (2022-03-24). "The Effect of First Language Transfer on Second Language Acquisition and Learning: From Contrastive Analysis to Contemporary Neuroimaging". RELC Journal. 55 (1): 162–178. doi:10.1177/00336882221081894. ISSN 0033-6882. S2CID 247720799.

- ^ a b Li, Hehui; Yuan, Qiming; Luo, Yue-Jia; Tao, Wuhai (June 2022). "A new perspective for understanding the contributions of the cerebellum to reading: The cerebro-cerebellar mapping hypothesis". Neuropsychologia. 170: 108231. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2022.108231. PMID 35378104. S2CID 247859931.

- ^ Alvarez, Travis A.; Fiez, Julie A. (September 2018). "Current perspectives on the cerebellum and reading development". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 92: 55–66. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.05.006. PMC 6078792. PMID 29730484.

- ^ "Eye Movements and Reading, Louisa Moats, Carol Tolman, Reading rockets". 2009.

- ^ Mark Seidenberg (2017). Language at the speed of light. Basic Books. pp. 61–66. ISBN 978-0-465-08065-6.

- ^ Bélanger, N. N.; Rayner, K. (2015). "What Eye Movements Reveal about Deaf Readers". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 24 (3): 220–226. doi:10.1177/0963721414567527. PMC 4651440. PMID 26594098.

- ^ "Average reading speed, Research Digest, The British Psychological Society". 13 June 2019. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ Brysbaert, Marc (December 2019). "How many words do we read per minute? A review and meta-analysis of reading rate". Journal of Memory and Language. 109: 104047. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2019.104047. S2CID 202267075.

- ^ Hunziker, Hans-Werner (2006). Im Auge des Lesers foveale und periphere Wahrnehmung: vom Buchstabieren zur Lesefreude (In the eye of the reader: foveal and peripheral perception – from letter recognition to the joy of reading) (in German). Transmedia Zurich. ISBN 978-3-7266-0068-6.[page needed]

- ^ Coltheart, Max; Curtis, Brent; Atkins, Paul; Haller, Micheal (1 January 1993). "Models of reading aloud: Dual-route and parallel-distributed-processing approaches". Psychological Review. 100 (4): 589–608. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.589.

- ^ Yamada J, Imai H, Ikebe Y (July 1990). "The use of the orthographic lexicon in reading kana words". The Journal of General Psychology. 117 (3): 311–323. PMID 2213002.

- ^ a b Pritchard SC, Coltheart M, Palethorpe S, Castles A (October 2012). "Nonword reading: comparing dual-route cascaded and connectionist dual-process models with human data". J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 38 (5): 1268–1288. doi:10.1037/a0026703. PMID 22309087.

- ^ Zorzi, Marco; Houghton, George; Butterworth, Brian (1998). "Two routes or one in reading aloud? A connectionist dual-process model". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 24 (4): 1131–1161. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.24.4.1131. ISSN 1939-1277.

- ^ Colin M MacLeod (December 18, 2011). "I said, you said: the production effect gets personal". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 18 (6): 1197–1202. doi:10.3758/s13423-011-0168-8. PMID 21938642. S2CID 11679593.

- ^ William R. Klemm (December 15, 2017). "Enhance Memory with the "Production Effect", Psychology today".

- ^ "Study finds reading information aloud to yourself improves memory, University of Waterloo". December 1, 2017.

- ^ "What Is Evidence-Based Reading Instruction and How Do You Know It When You See It?, U.S. Department of Education, March 2012" (PDF).

- ^ "Reading and the Brain, LD at school, Canada". 15 May 2015.

- ^ Suárez, N.; Sánchez, C. R.; Jiménez, J. E.; Anguera, M. T. (2018). "Is Reading Instruction Evidence-Based?, Frontiers in psychology, 2018-02-01". Frontiers in Psychology. 9: 7. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00007. PMC 5800299. PMID 29449818.

- ^ "Evidence based practices in schools, Reading Rockets". 12 January 2013.

- ^ Schwartz, Sarah (4 December 2019). "The Most Popular Reading Programs Aren't Backed by Science, EdWeek". Education Week.

- ^ "Best Evidence Encyclopedia". Best Evidence Encyclopedia.

- ^ "A Synthesis of Quantitative Research on Programs For Struggling Readers in Elementary Schools, 2021" (PDF).

- ^ "Home – Evidence for ESSA". Evidence for ESSA – Find Evidence-Based PK-12 Programs.

- ^ "Center for Research and Reform in Education". 13 September 2023.

- ^ "Widespread Support for New 'Evidence for ESSA'". Business Insider. 2017-02-28.

- ^ "Every student succeeds act". US Dept. of Education.

- ^ "Home". ProvenTutoring.Org.

- ^ "Success for All: Research Summary" (PDF). 8 September 2021.

- ^ "SFA/Science of reading program alignment". 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-05-13. Retrieved 2022-05-13.

- ^ a b "WWC | Find What Works!". ies.ed.gov.

- ^ "WWC | Reviews of Individual Studies". ies.ed.gov.

- ^ "WWC | Find What Works!". ies.ed.gov.

- ^ "BERA". www.bera.ac.uk.

- ^ "The role of research in teacher education: reviewing the evidence-BERA-RSA, January 2014" (PDF).

- ^ "Research and the Teaching Profession: Building the Capacity for a Self-Improving Education System-BERA-RSA". January 2014.

- ^ "Resource Database | Florida Center for Reading Research". fcrr.org.

- ^ "Institute of Education Sciences (IES) Home Page, a part of the U.S. Department of Education". ies.ed.gov.

- ^ "Synthesis of IES Research on Early Intervention and Early Childhood Education July 2013" (PDF).

- ^ "Publications & Products". ies.ed.gov.

- ^ "Home". NFER.

- ^ "Using Evidence in the Classroom: What Works and Why?". NFER. 2014. Archived from the original on 2021-01-18. Retrieved 2021-01-29.

- ^ "Research at Ofsted". GOV.UK.

- ^ "What Works? Research Into Practice". www.edu.gov.on.ca. Archived from the original on 2020-12-16. Retrieved 2021-01-29.

- ^ "Education and Literacy". www.rand.org.

- ^ a b "researchED Events for Researchers, Teachers & Policy Makers". ResearchED.

- ^ "Issue 1, Nr 1, June 2018".

- ^ Clinton, Virginia (2019-01-13). "Reading from paper compared to screens: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Research in Reading. 42 (2): 288–325. doi:10.1111/1467-9817.12269. S2CID 149835771.

- ^ Benjamin Herold (2014-05-06). "Digital Reading Poses Learning Challenges for Students, Education Week". Education Week.

- ^ Sarah Schwartz (2023-03-15). "Kids Understand More From Books Than Screens, But That's Not Always the Case, Education week". Education Week.

- ^ Susan B. Porter; Timothy N. Odegard; Emily A. Farris; Eric L. Oslund (2023-06-09). "Effects of teacher knowledge of early reading on students' gains in reading foundational skills and comprehension". Reading and Writing. 37 (8): 2007–2023. doi:10.1007/s11145-023-10448-w. S2CID 259619958.

- ^ a b c d "Will the Science of Reading Catch On in Teacher Prep?" (PDF). spotlight. Education week. 2020-03-12. pp. 12–15.

- ^ Sarah Schwartz (March 23, 2021). "Most States Fail to Measure Teachers' Knowledge of the 'Science of Reading,' Report Says, Education Week". Education Week.

- ^ California Reading Curriculum Report, California reading coalition (Report). 2021.

- ^ Sarah Schwartz (October 11, 2022). "States Should Recommend Better 'Science of Reading' Content, Report Says, Education week". Education Week.

- ^ "Youtube, Science of reading: Bridging the classroom gap, Mark Seidenberg". YouTube. June 4, 2019.

- ^ "Louisa Moats, Ed.D." www.louisamoats.com.

- ^ "Dr. Louisa Moats Talks Teachers And Reading Science with Dyslexia Live". YouTube. 2020-03-20.

- ^ "Nation's Report Card".

- ^ "Teaching, Reading & Learning: The Podcast". The Reading League.

- ^ "NAEP Reading: State Average Scores". www.nationsreportcard.gov.

- ^ Sarah Schwartz (July 20, 2022). "Which States Have Passed 'Science of Reading' Laws? What's in Them? Education Week".

- ^ School changes reading program after realizing students 'weren't actually learning to read', CNN national correspondent Athena Jones. 2023-04-24.

- ^ Sarah Schwartz (July 20, 2022). "States Are Pushing Changes to Reading Instruction. But Old Practices Prove Hard to Shake, EdWeek". Education Week.

- ^ Sarah Schwartz (July 20, 2022). "Why Putting the 'Science of Reading' Into Practice Is So Challenging, Edweek". Education Week.

- ^ Sarah Schwartz; Madeline Will (2023-03-28). "Why Some Teachers' Unions Oppose 'Science of Reading' Legislation". Education Week.

- ^ "Bill to mandate 'science of reading' in California classrooms dies, Edsource". April 12, 2024.

- ^ "A New Chapter for Arkansas Students, 2018 Report" (PDF).

- ^ "Amy Murdoch". www.msj.edu.

- ^ "English viewing and reading, k-2, EECD, NB" (PDF).

- ^ Government of New Brunswick, Canada (October 30, 2014). "Curriculum Development (Anglophone Sector)". www2.gnb.ca.

- ^ "ATLANTIC CANADA ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS CURRICULUM: GRADES 4–6, New Brunswick department of education" (PDF). 1998.

- ^ "The Ministry of Education thanks the Ontario Human Rights Commission for its Right to Read Inquiry report" (PDF). March 11, 2022.

- ^ "The Center for Literacy and Learning | Literacy & Education Professional Development". The Center for Literacy & Learning.

- ^ "The Science of Reading". The Reading League.

- ^ "Science of reading eBook, The reading league" (PDF).

- ^ "Science for Early Literacy Learning Really Matters, Psychology Today". July 16, 2020.

- ^ Timothy Shanahan (2021-05-15). "What if there is no reading research on an issue".

==