Exile of Caravaggio

The Lombard painter Michelangelo Merisi, known as "Caravaggio", was compelled to flee Rome, where he was accused of murder, in May 1606, and travel south through Italy, reaching as far as the island of Malta. His exile spanned slightly over four years, and concluded with his demise in July 1610 at the age of 38. This time coincided with the acquisition of a pardon that granted him the opportunity to return to Rome without the concern of facing legal retribution.

Following the commission of the murder that ultimately resulted in his death sentence in absentia, Caravaggio was initially compelled to hastily depart Rome and seek refuge in the Alban Hills of Lazio. He remained in this location for a brief period, spanning only a few months, before relocating to Naples in pursuit of enhanced safety. Subsequently, he embarked on a voyage to Malta, seeking refuge and the status of Knight of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem. However, he was compelled to flee the island after becoming embroiled in another violent incident. This led him to Sicily, where he resided in Syracuse, Messina, and Palermo. In 1609, he returned to Naples and embarked on a journey to Rome to obtain a pardon from Pope Paul V. He passed away under enigmatic circumstances on July 18, 1610, in the village of Porto Ercole.

It is estimated that Caravaggio produced at least twenty works during this period. The style he developed was highly distinctive and reflected the hardships of his life as an exile and a condemned man. His palette darkened significantly, his compositions evolved spatially, and the themes he explored became darker, more meditative, contemplative, and morbid. During this period, Caravaggio created monumental religious works and was commissioned to create portraits, intended for influential patrons whose favor he sought, including the possibility of intercession with the Pope to allow his return to Rome.

Context and conditions of exile

[edit]Flight from Rome

[edit]

Caravaggio was originally from Milan, but he relocated to Rome during the 1590s, where he gained recognition for his artistic contributions. By the turn of the century, Caravaggio's artistic success was at its zenith. However, his tempestuous temperament led him to engage in numerous confrontations with the law.[n 1] The most notable incident occurred on May 28, 1606, during festivities marking the anniversary of Pope Paul V's election. These celebrations were often characterized by altercations. During the aforementioned altercation, Caravaggio and his associate Onorio Longhi engaged in a physical confrontation with members and associates of the Tomassoni family, including Ranuccio Tomassoni and his brother Giovan Francesco, who, ironically, was described as a "keeper of order." The confrontation culminated in the death of Ranuccio Tomassoni, who was fatally wounded by Caravaggio, and Caravaggio himself sustaining injuries.[1]

The incident caused a sensation in the city, and rumors of varying accuracy quickly circulated. Some suggested that the altercation followed a game of pallacorda (similar to tennis) or occurred near a pallacorda court adjacent to the Palazzo Firenze.[2][3] Others speculated that it was related to gambling debts.[4] Another possibility is that the altercation stemmed from a dispute over a woman, specifically Fillide Melandroni, who was employed as a model for Caravaggio but also engaged in prostitution under Tomassoni's authority.[5] While the precise cause of the confrontation remains uncertain, the incident was likely rooted in an ongoing dispute. The enmity between Onorio Longhi and the Tomassoni family had been an enduring feature of their relationship, and it is conceivable that Caravaggio, by the prevailing code of honor, may have joined forces with Longhi in this act of retribution.[1]

After the incident, the participants dispersed to evade legal retribution. Longhi returned to his place of origin in Milan, while the surviving members of the Tomassoni group sought refuge in Parma.[6] Caravaggio initiated his exile in the Alban Hills[6] in the Lazio region, south of Rome.[7] The precise location of his exile remains a subject of debate, with potential destinations including Zagarolo, Palestrina, or Paliano. These areas offered sufficient distance for immediate safety, particularly since the region was under the control of the Colonna family, long-time patrons and protectors of Caravaggio.[8] However, his stay was brief. Caravaggio's situation became critical as the initially slow-moving Roman justice system soon proved severe. Within weeks, Caravaggio was sentenced in absentia to bando capitale—a lifetime banishment accompanied by a death sentence enforceable by anyone, anywhere. Facing this extreme threat, Caravaggio quickly fled farther south, beyond the reach of the Papal States, but still under Colonna protection. He traveled to Naples, then under Spanish control, likely before the end of September 1606.[9]

This sojourn in Latium, lasting several months, likely provided Caravaggio with an opportunity to produce select works, although the extant documentation does not permit definitive confirmation. These works may include Saint Francis in Meditation[10] and the other Saint Francis in Meditation on the Crucifix from Cremona,[11] as well as the Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy and the Supper at Emmaus, currently housed in Milan.[12] The David with the Head of Goliath in the Borghese Gallery may also have been created during this period.[13] However, some authors suggest a later creation, perhaps shortly before the artist died in 1610.[14]

Mediterranean wanderings

[edit]First stay in Naples

[edit]

Caravaggio's arrival in Naples occurred approximately four months after he departed from Rome, around late September 1606.[15] Despite his brief sojourn in the city, spanning a mere ten months, prior to his relocation to Malta, this period proved to be remarkably fruitful.[16] No extant records from this era make any mention of scandals, accusations, or criminal activities involving him.[17]

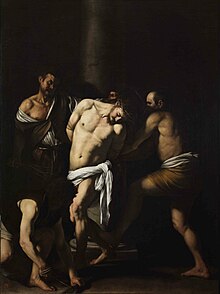

Caravaggio's arrival in Naples was met with great anticipation within the artistic community.[17] According to Giovanni Pietro Bellori, a near-contemporary biographer who provided commentary on Caravaggio's career several decades later, "immediately upon his arrival, he secured employment, as his style and name had already gained recognition."[18] Caravaggio swiftly obtained significant and lucrative commissions from local dignitaries, indicating his rapid ascent to prominence. These commissions included an altarpiece depicting a Virgin and Child, which has since been lost,[19] and a painting for another church, The Seven Works of Mercy.[15] Other works from this period include The Flagellation of Christ,[20] Salome with the Head of John the Baptist, and Christ at the Column.[21] The eighth Count of Benavente, the Spanish viceroy in Naples—then under Spanish rule[22] since the early 16th century—likely commissioned Caravaggio's Saint Andrew, which he took with him to Valladolid shortly afterward.[23]

It is also believed that during this Neapolitan period, Caravaggio painted Madonna of the Rosary[24] and David with the Head of Goliath,[16] assuming the latter was not completed shortly before his arrival in Naples.

Knight in Malta

[edit]

Caravaggio's arrival in Valletta, the fortified capital of Malta, on July 12, 1607,[25] coincided with the pursuit of an opportunity that would eventually lead to his initiation into the Knights of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem.[26] This endeavor was influenced by the aspirations of Alof de Wignacourt, the Grand Master of the Order, who prioritized the promotion and safeguarding of artistic endeavors.[27] As articulated by Giovanni Pietro Bellori, Caravaggio's motivations were to be recognized with the Cross of Malta, a distinction bestowed upon individuals exemplifying merit and virtue.[28] This aspiration underscores Caravaggio's ambition to attain a form of nobility and social advancement, particularly notable given his humble origins. Concurrently, this endeavor was probably a component of his broader strategy to obtain a papal pardon, which would have enabled him to eventually return to Rome.[29]

According to several biographers, there is a possibility that Caravaggio's sojourn in Malta was momentarily interrupted by a sojourn in Naples between September 1607 and the end of April 1608, before his return to Malta. This would suggest the existence of two distinct Maltese periods.[30]

However, Caravaggio's sojourn in Malta was abruptly curtailed, culminating in yet another episode of violence. Less than three months after attaining the highly sought-after rank of knight, on the night of August 18, 1608, he found himself embroiled in a physical altercation at the residence of one of the Order's brothers, who happened to be an organist at a church in Valletta. The ensuing confrontation led to grave injuries sustained by one of the Hospitallers.[31] Caravaggio, along with several others, was apprehended—or at least detained—but managed to evade capture before facing trial. By early October, presumably with the assistance of allies, he escaped from the Fort St. Angelo and embarked on a voyage to Sicily.[32] An immediate investigation was initiated in Malta, but it did not yield any definitive results. The case culminated in a declaration of escape and high treason, resulting in Caravaggio's expulsion from the Order in November 1608 and his formal degradation as a knight, described as tan[quam] membrum putridum et foetidum ("as a putrid and corrupted member").[33]

A close examination of Caravaggio's artistic output during his Maltese period reveals a surprising paucity of productivity, given his customary rapid execution of works and the fact that he resided in Malta for a period of fifteen months. It is estimated that he completed no more than five paintings during this time.[27]

Flight to Sicily

[edit]

Caravaggio arrived in the southern region of Sicily and embarked on an adventurous journey, traveling on foot to Syracuse.[36] He made only a brief stop there, likely meeting his friend Mario Minniti, who may have assisted him in securing the commission for The Burial of Saint Lucy.[37] However, despite the success of his work, Caravaggio felt unsafe[n 2] and immediately left the city after delivering the painting.[38] He then sought refuge in Messina under the patronage of Archbishop Giannettino Doria, a relative of the Marchioness Costanza Sforza Colonna, a long-time patron of Caravaggio.[39] In Messina, Caravaggio completed a painting titled The Raising of Lazarus, commissioned by a wealthy merchant,[40] Giovan Battista de' Lazzari, whose name was derived from the Christian saint.[41] In this work, as well as in The Burial of Saint Lucy, Caravaggio defied traditional iconography, employing bold and innovative techniques.[41] Subsequently, he created Adoration of the Shepherds for a Franciscan church in Messina.[42] Other commissions from this period include four paintings on the Passion of Christ, though it is uncertain whether these works were ever completed.[43]

Caravaggio's departure from Messina and subsequent arrival in Palermo, the vibrant city in western Sicily, possibly occurred due to another violent incident, perhaps a dispute with a professor.[44] This relocation is believed to have taken place[45] in the summer of 1609.[46] In Palermo, Caravaggio created an additional altarpiece for the Franciscans, titled Nativity with Saint Francis and Saint Lawrence. This artwork subsequently disappeared following its theft in 1969, likely by members of the local mafia.[46] Caravaggio's sense of peril, compounded by alleged persecution at the hands of his adversaries, as documented in the biographies of Bellori and Baglione, ultimately compelled him to depart from Sicily. He returned to Naples, anticipating the long-awaited papal pardon from Rome.[46]

The Sicilian altarpieces created by Caravaggio garnered him widespread acclaim and had a profound and lasting impact on local artists. These artists, including Mario Minniti, Filippo Paladini, and Alonzo Rodriguez, adopted Caravaggio's techniques,[47] such as dramatic lighting contrasts and the use of realistic, contemporary models with expressive gestures. While their interpretations occasionally lacked subtlety, they contributed to conveying the emotional intensity that is widely admired in Caravaggio's work.[48]

Return to Naples and death

[edit]

Concrete evidence places the artist known as Caravaggio in Naples in late October 1609. A report reveals that he was the victim of a violent tavern attack, leaving his face disfigured—a detail confirmed in a letter written by Mancini in early November.[49][n 3] Despite this, Caravaggio once again achieved great success upon his return to Naples,[50] securing significant commissions, including The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula for the Genoese prince Marcantonio Doria. Other works, such as Resurrection of Christ for Sant'Anna dei Lombardi,[51] are believed to have been produced during this period, though they are either lost or undocumented. Despite its brevity—spanning from October 1609 to July 1610—this second stay in Naples was remarkably prolific. According to Helen Langdon, Caravaggio's style underwent a significant shift during this time, becoming more somber and unpolished, and directly addressing themes of death and human sin.[52]

Caravaggio finally departed from the port of Naples at Chiaia to return to Rome,[50] where he sought the long-awaited papal pardon.[51] The precise circumstances of his journey are not well documented, but it seems clear that the felucca on which he sailed carried several of his paintings, possibly intended for Cardinal Scipione Borghese as a reward for his judicial efforts in the artist's favor. However, the felucca returned without Caravaggio to its home port, as the artist died at Porto Ercole on July 18, 1610.[51] The vessel and its cargo were subsequently sent back to Naples and the Cellamare Palace of Costanza Colonna. According to the Apostolic Nuncio Deodato Gentile, three paintings were found on board: two depictions of Saint John the Baptist (one possibly being the version in the Borghese Gallery) and one of Mary Magdalene.[53]

The various reports and accounts exchanged in the days following Caravaggio's death unanimously confirm that he had received the Pope's pardon. Thus, had he survived, he would have been able to return to Rome to resume his life and career.[54]

Late style

[edit]Works of redemption

[edit]

A close examination of Caravaggio's oeuvre reveals a direct response to his immediate needs for shelter, sustenance, and—most significantly—the protection of influential patrons. A case in point is the series of two portraits of dignitaries from the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem: one of Grand Master Alof de Wignacourt and another of Antonio Martelli, a knight of justice of the highest rank.[55] Each new commission completed in Malta enhanced Caravaggio's standing, thereby facilitating his access to the circles of power and the potential for attaining knighthood.[56] When Grand Master Wignacourt petitioned the Pope to allow Caravaggio to be named a knight despite his criminal record, Caravaggio once again employed his art as a means to secure his position. The admission fee, known as the passaggio, was met through the contribution of a painting—the imposing The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist.[57]

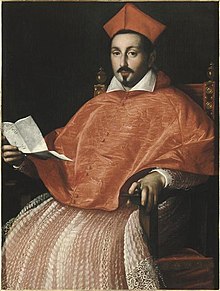

It is plausible that some of Caravaggio's works produced during his period of exile were conceived as diplomatic appeals to his patrons, seeking their assistance in securing a papal pardon that would facilitate his return to Rome. During this era, even crimes involving bloodshed frequently received a pardon, provided the offender was a distinguished artist capable of offering valuable artistic contributions in return.[58] An example of this phenomenon is David with the Head of Goliath, which was intended for Cardinal Scipione Borghese, who presided over the papal court's judicial affairs. Given his influential position, Borghese was a pivotal figure with the potential to assist the fugitive.[59] Another significant ally was Cardinal Benedetto Ala, the president of the papal tribunal and the possible recipient of Saint Francis in Meditation, which is currently housed in Cremona, Ala's hometown.[58] Cardinal Ferdinando Gonzaga, who commissioned Annunciation, was also among Caravaggio's influential supporters.[43]

Beyond their utilitarian purpose, several commentators have suggested that some of Caravaggio's paintings served a redemptive function, consciously or unconsciously. This interpretation aligns with the guilt likely felt by a man who had killed another in a street fight, as exemplified by Caravaggio's self-portrait as Goliath in David with the Head of Goliath. In this painting, the artist depicts himself as decapitated, with a faint glimmer of life still visible in his eyes—a haunting image reminiscent of a condemned soul doomed to wander.[60] Similarly, The Raising of Lazarus has been seen by some as a metaphor for Caravaggio's struggle for salvation, paralleling Lazarus' triumph over death with the artist's desperate quest for redemption.[61]

Furthermore, various commentators have noted a growing sense of humanity in the artist's works produced during his exile—an emotional depth that would define his work until his death.[62] Keith Christiansen has observed that this exile allowed Caravaggio to free himself from certain artistic constraints and controversies tied to the Roman context. No longer bound by the legacies of Michelangelo or Raphael, nor the references to antiquity that were so significant in Roman culture, Caravaggio was able to adopt a more introspective approach, particularly in his exploration of the emotional truth hidden within biblical narratives.[63]

Toward the shadows

[edit]

The 1606 version of The Supper at Emmaus, painted at the onset of Caravaggio's flight and just five years after the luminous first version, evinces a marked evolution in palette and composition. As Andrew Graham-Dixon writes, the shadows deepen so much that it feels as though someone has extinguished the light illuminating the scene.[64] This transition toward tenebrism, coupled with a heightened naturalism, is particularly evident in Caravaggio's body of religious works produced in Naples during his two sojourns in the city. These works exerted a profound influence, giving rise to a distinctive Neapolitan school of painting in the subsequent decades. This school influenced notable artists such as José de Ribera, Mattia Preti, and Luca Giordano.[25] Notable artists such as Carlo Sellitto and Battistello Caracciolo began emulating Caravaggio's style, creating copies of his altarpieces, a practice that was also adopted by foreign artists, including the Flemish painter Louis Finson. This diffusion of Caravaggism contributed to the dissemination of his artistic influence throughout Europe.[65]

The shift in Caravaggio's artistic style, marked by a darkening of his canvases, signaled a departure from the lyricism that characterized his earlier works.[61] This transition is believed to reflect the mental and psychological state the artist experienced during his exile. Notably, the use of shadows in Caravaggio's Roman period was primarily a technical choice, but in exile, these shadows acquired a profoundly psychological dimension.[63] While many of the paintings from this period served Caravaggio's objective of obtaining a pardon and returning to Rome, they also offer a glimpse into the artist's somber introspection. This introspective quality is exemplified in the contemplative Saint John the Baptist, a work intended for Cardinal Scipione Borghese.[66] In contrast, the artist's later works are characterized by a pervasive sense of tragedy and evoke a profound personal despair. Helen Langdon notes that the final self-portrait Caravaggio included in a painting, The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula (possibly his very last work[67]), revisits his earlier self-depiction in The Taking of Christ. However, this subsequent iteration exhibits a marked absence of vitality and fervor, suggesting a stark departure from the exuberance and opulence that characterized the earlier work.[50]

- The same self-portrait, but one that bears witness to the loss of all hope.

-

Detail from L'Arrestation du Christ (1602).

-

Detail from Martyre de Sainte Ursule (1610).

This evolution toward shadows, when considered in conjunction with the deterioration of several late canvases, should not lead one to assume that Caravaggio's palette uniformly darkened. On the contrary, he sometimes employed a wide range of colors, particularly in his Sicilian altarpieces.[68] However, his palette did become more restrained in his final works, yet he continued to use vibrant and contrasting colors. For instance, the use of white became increasingly prominent, intensifying the effects of light,[69] while red was frequently used to emphasize details or as a dominant tone, as seen in the vermilion hues of Saint Jerome in Valletta and The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula.[70]

A reimagined space

[edit]

A comparative analysis of Caravaggio's Roman altarpieces and those from Malta or Sicily reveals a significant evolution in his vision of spatial composition during his later period.[72] His figures, once confined to the edges of paintings, now occupy more space within clearly delineated architectural frameworks.[73] This shift, while maintaining the rigor and precision characteristic of Caravaggio's earlier works,[71] also introduces a new depth to his compositions.[68] Though occasionally obscured by the deteriorated state of certain Sicilian canvases, the backgrounds were nonetheless meticulously rendered.[73] Helen Langdon observes that the spatial dimensions inhabited by Caravaggio's figures appear to expand in comparison to those depicted in his Roman works.[73] Christiansen characterizes this transformation as Caravaggio's discovery during his exile of "the tragic eloquence of emptiness."[63]

List of paintings from the period

[edit]According to experts in the field, approximately twenty paintings created by Caravaggio during his exile can be definitively ascribed to him. However, some attributions remain the subject of scholarly debate. Art historian Catherine Puglisi identifies thirteen altarpieces and potentially around a dozen easel paintings.[22] This later corpus of works is comparatively better documented than his early productions, as Caravaggio had by then achieved widespread renown in Rome, thereby enhancing the quality and quantity of records concerning his oeuvre.

Current catalogue

[edit]The following list of works and proposed creation dates are derived from Caravaggio by John T. Spike, which provides a detailed analysis of the attributions and datings suggested by other art historians, synthesizing them into a relatively consensual overview.[74] However, these attributions are often hypotheses rather than definitive conclusions and should therefore be cross-referenced with other sources. For instance, Spike's list of 27 paintings attributed to this exile period can be compared to Sybille Ebert-Schifferer's catalogue, which identifies only 21 paintings for the same period,[75] or to Catherine Puglisi's catalogue, which includes as many as 28.[76]

Paintings and dates that remain frequently contested or debated are marked with an asterisk (*).

- The Seven Works of Mercy (1606)

- Supper at Emmaus (1606)

- Madonna of the Rosary (1606-1607*)[n 4]

- The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew (1607*)[n 5]

- The Denial of Saint Peter (v.1607*)[n 6]

- The Flagellation of Christ (1607*)[n 7]

- Christ at the Column (v.1607*)[n 8]

- Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt and his Page (1607)

- Saint Jerome Writing (v.1607)

- The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (1608)

- The Burial of Saint Lucy (1608)

- Portrait of Fra Antonio Martelli (v.1608)[n 9]

- Saint Francis in Meditation (1608*)

- John the Baptist (v.1608*)[n 10]

- Salome with the Head of John the Baptist (v.1608*)[n 11]

- Sleeping Cupid (1608)

- The Raising of Lazarus (1608-1609)

- Annunciation (1608-1610*)[n 12]

- Narcissus (1608-1610)

- Adoration of the Shepherds (1609)[n 13]

- Nativity with Saint Francis and Saint Lawrence (1609)

- Saint John the Baptist (1609-1610)[n 14]

- Salome with the Head of John the Baptist (1609-1610*)

- The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula (1610)

- David with the Head of Goliath (1610*)[n 15]

- Mary Magdalen in Ecstasy (1610*)[n 16]

- Reclining John the Baptist (1610*)[n 17]

Possible additions

[edit]

Beyond the above catalogue, various contemporary researchers have proposed the inclusion of other works from this period of exile. However, these proposals have not garnered scholarly consensus.

- Saint Francis in Meditation[n 18]

- Ecce Homo[104]

- The Tooth Puller[104]

- The Resurrection of Christ,[105] a now-lost painting, along with two other lost paintings believed to have been designed to decorate the Fenaroli Chapel in the Church of Sant'Anna dei Lombardi in Naples.

Exhibitions

[edit]- From October 2004 to January 2005, a major exhibition assembled 18 paintings from the period 1606–1610 at the Capodimonte Museum in Naples under the title L’Ultimo Tempo.[63]

- The exhibition then moved to London from February to May 2005, featuring a similar corpus but limited to 16 paintings, under the title The Final Years at the National Gallery.[106][107]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Archival research uncovered, for instance, a police document reporting Caravaggio’s arrest for illegal possession of a weapon, just one year before committing the murder that forced him into exile. The historical document is available and analyzed in this article:

- ^ Contrary to this hypothesis, S. Ebert-Schifferer argues that concerns for his safety did not drive Caravaggio’s movements across Sicily. Instead, she suggests he traveled from city to city based on commissions without fearing specific threats (Ebert-Schifferer 2009, p. 233).

- ^ Many theories surround this attack, which could be interpreted as an ambush. Was it revenge by Alof de Wignacourt or the family of Ranuccio Tommasoni? A. Graham-Dixon argues that it was more plausibly retaliation for the brawl in Malta that led to Caravaggio’s arrest. In this hypothesis, the instigator of the vendetta would have been Giovanni Rodomonte Roero, Count of Vezza (Graham-Dixon 2010, pp. 419–420).

- ^ Art historians are divided on whether certain works were produced in Naples between September 1606 and July 1607[77] or created earlier in Rome, around 1604–1605.[78]78 The debate is complicated by the lack of documentation about the commissioner of the work.[79]

- ^ Commissioned before the end of 1607 by the Viceroy of Naples, this painting was most likely completed in the same year.[80] However, the Cleveland Museum, which houses it, proposes a date range of 1606–1607.[81]

- ^ While the attribution of this painting to Caravaggio is undisputed, its precise dating is complicated by its condition and the lack of archival records tracing its provenance before 1945. John T. Spike, therefore, proposes an “open” dating ranging from approximately 1607 to 1610.[82]

- ^ This Flagellation slightly precedes another version preserved in Rouen, commonly called Christ at the Column. Technical analyses have revealed numerous and significant revisions (pentimenti), which some authors interpret as an indication that the painting was possibly started in 1607 but later revised, completed, or modified in 1610 when Caravaggio returned to Naples.[83]

- ^ By the late 17th century, various art collection inventories already referenced multiple Flagellations attributed to Caravaggio, complicating efforts to establish a stable catalogue. For instance, the present Flagellation of Christ (or Christ at the Column) was initially acquired by the Rouen Museum in 1955 as a work by Mattia Preti.[84] Roberto Longhi was the first to reattribute it to Caravaggio in 1960, an opinion now universally accepted.[85] Copies from the period further support its creation during Caravaggio’s first stay in Naples.[85]

- ^ After being overlooked for a long time in Florentine collections (the Martelli family was from Florence), this portrait was reattributed to Caravaggio by Mina Gregori in 1966, though the model’s identity was not confirmed until the late 1990s.[86]

- ^ The John the Baptist at the Fountain or at the Spring is not definitively attributed to Caravaggio. Multiple copies exist, and identifying the autograph version remains uncertain. However, Gérard-Julien Salvy and others argue that it likely dates to Caravaggio’s Sicilian period.[87]

- ^ Found in a private French collection in 1959, the dating of this painting remains uncertain.[88] Despite ongoing debates, its attribution to Caravaggio and placement in his exile period (1607–1610) are now widely accepted.[89] Its style suggests it was likely executed during the first Neapolitan period, though it may have accompanied Caravaggio to Malta.[89]

The theme of Salome with the Head of the Baptist appears in another painting now in Madrid, believed to have been produced around 1609, possibly during Caravaggio’s return to Naples.[90] The existence of two versions of the same theme complicates their dating and identification. Both are likely from Caravaggio’s late period. Bellori suggests that when Caravaggio returned to Naples, he sent this painting to Malta as a gift to appease Grand Master Wignacourt.[91] However, it remains uncertain whether the Salome in Madrid is the one Bellori referenced. Consensus generally supports a late-life date for both paintings.[92] Roberto Longhi already proposed this timeline in 1927.[91] An opposing argument based on technical analysis suggests that the Salome in London, rather than the Madrid version, may be the later painting cited by Bellori. See Keith, pp. 46–49, for further discussion.[93] - ^ Unfinished and damaged, this painting presents numerous challenges in determining its precise origin. The Nancy museum, which houses it, cautiously dates it to the period 1607-1610, duinter's exile.[94] However, some authors believe it was started during his stay in Messina, commissioned by Cardinal Gonzaga, who was working on Caravaggio's judicial rehabilitation.[43]

- ^ Stolen in situ from the San Lorenzo Oratory in Palermo in 1969, this painting has remained missing ever since.[95]

- ^ A consensus has gradually emerged placing the creation of this Saint John the Baptist not in Caravaggio's Roman period but in his later period, most likely in 1609 or 1610. It could be the second Baptist depicted in the felucca that carried the painter from Naples to Rome.[96]

- ^ The late dating of this painting is not certain: several authors prefer to place it in 1606-1607, that is, at the very beginning of the exile.[97] However, other arguments suggest that the second Neapolitan period might be more logical, based on stylistic elements as well as the treatment of the theme: the condemned man's plea to his potential protectors is very evident here.[98]

- ^ Mancini (later echoed by Bellori in similar terms) asserts that a Mary Magdalene was painted at the same time as the Supper at Emmaus, and that Costa would be the recipient of both works.[99] But other archives, dating from 1610, indicate the presence of a Mary Magdalene among the very last paintings Caravaggio may have left behind at the time of his death.[99] Both hypotheses place the creation of this painting during the painter's exile: either at the very beginning or the very end.

- ^ The dating and even the attribution of this painting to Caravaggio are disputed. Researchers, however, suggest that it could be the Saint John the Baptist that Caravaggio had in his possession when he died on the way back to Rome, accompanied by a second Saint John the Baptist and a Mary Magdalene (mentioned earlier for the Mary Magdalen in Ecstasy).[100]

- ^ The dating of the two Meditating Saint Francises is contested, but both could fit into this early period of flight. The one in Rome, discovered in 1968 in a convent in Latium, may have been made for Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini.[10] The one in Cremona, for Cardinal Benedetto Ala.[58] Regarding this second painting, aside from the hypothesis of Cardinal Ala (Archbishop of Urbino) as the first recipient, the name of Ottavio Costa is also mentioned. Nothing is certain, not even the dating, as the painting could be later (1608 according to some estimates) and thus postdate Caravaggio’s stay in Latium.[101] It is also considered that a century later, the painting may have passed through the collection of Mgr Paul Alphéran de Bussan, Bishop of Malta,[102] which could lend credibility to the theory of its creation in Malta.[103]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Ebert-Schifferer 2009, p. 193

- ^ Salvy 2008, p. 202

- ^ Bolard 2010, p. 157

- ^ Langdon 2000, p. 311

- ^ Langdon 2000, p. 313

- ^ a b Langdon 2000, p. 310

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer 2009, p. 195

- ^ Langdon 2000, pp. 315–316

- ^ Bolard 2010, p. 162

- ^ a b Bolard 2010, p. 161

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer 2009, pp. 197–198

- ^ Langdon 2000, p. 316

- ^ Graham-Dixon 2010, p. 332

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, p. 403

- ^ a b Ebert-Schifferer 2009, p. 201

- ^ a b Ebert-Schifferer 2009, p. 211

- ^ a b Bolard 2010, p. 165

- ^ Bellori 1991, p. 30

- ^ Puglisi 2005, p. 261

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer 2009, p. 202

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer 2009, p. 205

- ^ a b Puglisi 2005, p. 259

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer 2009, pp. 208–209

- ^ Puglisi 2005, pp. 271–275

- ^ a b Puglisi 2005, p. 277

- ^ Puglisi 2005, p. 278

- ^ a b Puglisi 2005, p. 279

- ^ Bellori 1991, p. 32

- ^ Bolard 2010, p. 175

- ^ Salvy 2008, p. 239

- ^ Salvy 2008, p. 257

- ^ Salvy 2008, p. 259

- ^ Salvy 2008, pp. 260–261

- ^ Salvy 2008, p. 83

- ^ Bolard 2010, pp. 196–197

- ^ Graham-Dixon 2010, p. 393

- ^ Salvy 2008, p. 261

- ^ Graham-Dixon 2010, p. 402

- ^ Salvy 2008, p. 267

- ^ Graham-Dixon 2010, p. 404

- ^ a b Salvy 2008, p. 269

- ^ Graham-Dixon 2010, p. 410

- ^ a b c Salvy 2008, p. 277

- ^ Langdon 2000, p. 376

- ^ Salvy 2008, pp. 277–278

- ^ a b c Graham-Dixon 2010, p. 413

- ^ Puglisi 2005, pp. 337–338

- ^ Puglisi 2005, p. 338

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer 2009, p. 233

- ^ a b c Langdon 2000, p. 388

- ^ a b c Ebert-Schifferer 2009, p. 234

- ^ Langdon 2000, p. 383

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer 2009, pp. 234–237

- ^ Langdon 2000, p. 390

- ^ Graham-Dixon 2010, pp. 372–373

- ^ Graham-Dixon 2010, p. 370

- ^ Graham-Dixon 2010, p. 375

- ^ a b c Ebert-Schifferer 2009, p. 198

- ^ Graham-Dixon 2010, p. 333

- ^ Graham-Dixon 2010, pp. 332–333

- ^ a b Puglisi 2005, p. 327

- ^ Salvy 2008, p. 215

- ^ a b c d Christiansen, Keith (December 12, 2004). "The Bounty of Caravaggio's Glorious Exile". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Graham-Dixon 2010, p. 330

- ^ Langdon 2000, p. 338

- ^ "San Giovanni Battista". Galleria Borghese. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Graham-Dixon 2010, p. 423

- ^ a b Puglisi 2005, p. 334

- ^ Puglisi 2005, p. 379

- ^ Puglisi 2005, p. 380

- ^ a b Christiansen, Keith (December 8, 2010). "Low Life, High Art". The New Republic. Archived from the original on July 20, 2024. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Puglisi 2005, pp. 333 et seq.

- ^ a b c Puglisi 2005, p. 333

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, pp. 281–406

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer 2009, pp. 294–298

- ^ Puglisi 2005, pp. 405–411

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, p. 285

- ^ Schütze & Taschen 2015, p. 289

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, p. 290

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, p. 309

- ^ "The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew, 1606-1607". Musée d'art de Cleveland. Archived from the original on July 20, 2024.

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, p. 320

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, p. 305

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, pp. 313–314

- ^ a b Spike & Spike 2010, p. 315

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, p. 337

- ^ Salvy 2008, p. 276

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, p. 321

- ^ a b Spike & Spike 2010, p. 323

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer 2009, p. 297

- ^ a b Spike & Spike 2010, p. 367

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, p. 369

- ^ Keith, Larry (1998). "Three Paintings by Caravaggio". National Gallery Technical Bulletin. 19: 46–49. Archived from the original on April 23, 2024.

- ^ Nancy, Ville de. "Peinture du XVIIe siècle" [17th century painting]. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nancy (in French). Archived from the original on February 8, 2023.

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, p. 377

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, p. 384

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer 2009, p. 295

- ^ Langdon 2000, pp. 384–386

- ^ a b Spike & Spike 2010, p. 281

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, pp. 396–397

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, pp. 331–332

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, p. 332

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, p. 334

- ^ a b Puglisi 2005, p. 410

- ^ Spike & Spike 2010, p. 306

- ^ Campbell, Peter (31 March 2005). "Caravaggio's final years". London Review of Books. 27 (7). Archived from the original on July 25, 2024. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Mctighe, Sheila (2006). "The End of Caravaggio". The Art Bulletin. 88 (3): 583–589. doi:10.1080/00043079.2006.10786307. JSTOR 25067269.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bellori, Giovan Pietro (1991). Vie du Caravage [Life of Caravaggio]. Le Promeneur (in French). Paris: Éditions Gallimard. ISBN 2-07-072391-7.

- Bolard, Laurent (2010). Caravage : Michelangelo Merisi dit Le Caravage, 1571-1610 [Caravaggio: Michelangelo Merisi, known as Caravaggio, 1571-1610] (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-63697-9. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018.

- Ebert-Schifferer, Sybille (2009). Caravage [Caravaggio] (in French). Paris: éditions Hazan. ISBN 978-2-7541-0399-2.

- Graham-Dixon, Andrew (2010). Caravaggio : a life sacred and profane. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-241-95464-5. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023.

- Langdon, Helen (2000). Caravaggio : a life. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3794-1.

- Puglisi, Catherine (2005). Caravaggio. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-3416-0.

- Salvy, Gérard-Julien (2008). Le Caravage [Caravaggio]. Folio biographies (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 978-2-07-034131-3.

- Schütze, Sebastian; Taschen, Benedikt (2015). Caravage : l'œuvre complète [Caravaggio: the complete works] (in French). Cologne and Paris: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-0182-8.

- Spike, John T; Spike, Michèle K (2010). Caravaggio : Catalogue of Paintings (2nd ed.). New York/London: Abbeville Press. ISBN 978-0-7892-1059-3. Archived from the original on August 21, 2021.