George Wickham

| George Wickham | |

|---|---|

| Jane Austen character | |

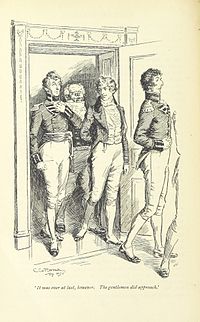

First appearance of Mr Wickham, as drawn by Henry Matthew Brock | |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Officer of the Militia |

| Spouse | Lydia Bennet |

| Relatives |

|

George Wickham is a fictional character created by Jane Austen who appears in her 1813 novel Pride and Prejudice. George Wickham is introduced as a militia officer who has a shared history with Mr. Darcy. Wickham's charming demeanour and his story of being badly treated by Darcy attracts the sympathy of the heroine, Elizabeth Bennet, to the point that she is warned by her aunt not to fall in love and marry him. It is revealed through the course of the story that George Wickham's true nature is that of a manipulative unprincipled layabout, a ne'er-do-well wastrel, compulsive liar and a degenerate, compulsive gambler, a seducer and a libertine, living the lifestyle of a rake. Lacking the finances to pay for his lifestyle, he gambles regularly (not just because he is a degenerate compulsive gambler and has no sense of economy) and cons credit from tradesmen and shopkeepers and skips out on paying-up.

Jane Austen's inspiration for the plot developed around the character of George Wickham was Tom Jones, a novel by Henry Fielding, where two boys – one rich, one poor – grow up together and have a confrontational relationship when they are adults.

A minor character, barely sketched out by the narrator to encourage the reader to share Elizabeth's first impression of him, he nonetheless plays a crucial role in the unfolding of the plot, as the actantial scheme opponent, and as a foil to Darcy.

Genesis of the character

[edit]

Henry Fielding's Tom Jones influenced the development of Wickham's character. He has traits of the main protagonists of The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling: the hero, Tom Jones, and his half-brother, Blifil.[1] There is a deliberate resemblance between the confrontational relationship between the two characters in Fielding's novel and in the one created by Jane Austen between Wickham and Darcy. Finally, the Pemberley estate, under the authority of Mr. Darcy, Senior, recalls the property of the wise Squire Allworthy of Paradise Hall.[2]

At the beginning of her novel, Jane Austen gives Wickham the appearance of a hero by his good looks and distinguished manners: he is reminiscent of Tom Jones, the foundling, unfairly banned from the squire's estate by the severe and pretentious Blifil, son of Bridget, the squire's sister. Master Blifil and the bastard Tom grew up in the same estate, and have received the same education and the same affection from the squire.[3] Blifil is rather strict and reserved; Tom, a jolly lad who pleases the ladies (both young and old), generous but impulsive and not strictly honourable, is too easily moved by a pretty face and has a tendency to put himself in difficult or scabrous situations.

But while Tom Jones, who has an upright soul, overcomes his misfortunes and shows nobility of character, Wickham does not correct himself because he hides a corrupt soul under his beautiful appearance. Like the treacherous Blifil, Wickham is permanently banned from the "paradise" of his childhood.[2]

It is also possible that Jane Austen was influenced, for the relationship between Wickham and Darcy, by Proteus and Valentine, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, created by Shakespeare; at least, that is the opinion of Laurie Kaplan, who recalls how subtly Jane Austen borrows from the Shakespearean comedy. Proteus, though a son of a gentleman, is intoxicated by the facilities and the luxury of the Court of Milan, where he has been sent by his father, and behaves very badly towards his childhood friend, Valentine, betraying and slandering him, causing his exile, while Valentine never stops, even in adversity, behaving nobly.[4]

Another parallel of Wickham and Darcy's younger days is with the Biblical figures Jacob and Esau.[5]

Another inspiration is Joseph Surface from The School for Scandal, who, like Wickham, "seems to be charming and upright but in fact is a thorough going villain".[6]

Henry Austen is regarded as an obvious inspiration for the character of George Wickham by Claire Tomalin, who cites Henry and Wickham's inability to settle on a career or a bride, and as Wickham, like Henry, "shows himself to be more agreeable than reliable".[7]

Sheryl Craig suggests that Wickham is named after the contemporary spymaster William Wickham, who was a figure of some notoriety at the time. According to her, "Jane Austen's first readers would have immediately connected the surname Wickham with deception, secrets, spies, and disappearing money."[8]

Plot

[edit]First impressions

[edit]

Once he appears at Meryton, Wickham is noticed, especially by the Bennet sisters: his youth, his manly beauty, his distinguished look and bearing speak immediately in favour of this handsome stranger seen in the street. He has all the appearance of the ideal romantic hero.[9] The uniform, the red coat of Colonel Forster's militia, adds to his prestige among the women.[n 1] Once he is introduced by Lieutenant Denny, the friend he accompanied, he displays friendly manners and "a happy readiness of conversation – a readiness at the same time perfectly correct and unassuming".[10] Susan Morgan notes that in contrast to Austen's introductions of other characters, Wickham's introduction "tells us nothing of Mr. Wickham's qualities or nature, but only of his looks and manners".[11] Elizabeth Bennet, in particular, is "delighted": she finds him well above the captains of the militia in elegance and manners. That is why, when her aunt, Mrs Philips, invited some officers and her nieces to her home the following evening, she is flattered to be "the happy woman" with whom Wickham spends most of the first evening.[12] He seems to her much more worthy of interest when he appears to be an innocent victim of the cruelty and jealousy of Mr. Darcy, whom she finds so unpleasant.[13]

As the narrator reveals nothing of the new officer's past,[n 2] he is seen exclusively through the positive image that Elizabeth and other characters form of Wickham – in particular Mrs. Gardiner, her aunt. A native of Derbyshire, where she had lived "ten or twelve years before her marriage", he gave her the opportunity to evoke pleasant memories of youth, so she was inclined towards him.[n 3] And if she puts Elizabeth on guard when she sees the interest her niece has in him, it is not that she does not trust him, but, as he has no money,[n 4] it would be very "imprudent" on the part of her niece to fall in love and marry him.[17] According to David Shapard, the only reason why Wickham and Elizabeth do not seriously consider marriage is that they are both without funds.[18] The Bennets, who were offended by the snobbery of Darcy and of Bingley's sisters, welcome him and listen to the story of his grievances with sympathy and without mistrust. Mr. Bennet himself has a certain weakness for him.[19] Jennifer Preston Wilson asserts that Wickham relies upon making a very good first impression and carefully reading his audience to find out their sympathies.[5]

An "interesting" young man

[edit]The first appearance of Wickham in Meryton is when Darcy and Elizabeth meet again after Elizabeth and Jane's stay in Netherfield, when the latter was sick.[19] The scene takes place in the street where the Bennet ladies, accompanied by the ridiculous and pompous Mr. Collins,[n 5] come to make the acquaintance of Wickham, when they are joined by Darcy and Bingley who are just crossing the city on horseback. Only Elizabeth, burning to know the explanation, notices the brief exchange between Wickham and Darcy: one turned red, the other pale.[10] As all the focus is on Elizabeth noticing this exchange between the men, Burns suggests that we are not told that Wickham is observing Darcy and Elizabeth as well.[19]

Wickham profits from the sympathy enjoyed in the city by Colonel Forster and his regiment choosing Meryton as its winter quarters. It is one of the local militias raised to reinforce the army against the threat of French invasion.[n 6] The presence of officers, generally young people from good families, disrupts the routine of local social life: they participate in community life, inviting gentlemen to the mess, and being invited themselves to balls, evening socials, and receptions. As some came with their spouses, teas and visits between women increased the occasions for marriageable young ladies to meet these dashing idle officers in red coats.[n 7] England was at war, the population feared an invasion, the army was recruiting and the prestige of the regimental uniform was therefore total.[21] It was possible for a new militia officer to make a fresh start in life, as Wickham's rank could be obtained without having to live in the local area.[22] In addition, according to the Cambridge Chronicle of 3 January 1795, the Derbyshire Militia, which Deidre Le Faye suggests inspired Jane Austen, was very well behaved in the two towns of Hertfordshire where it was stationed, as well as in church.[23]

Only Mr. Bingley and his sisters, Mr. Darcy's friends, consider he is not respectable and he behaved in an undignified way towards the latter, but they ignore the details of the story. They only know that Darcy "cannot bear to hear George Wickham mentioned."[24] In any case, they quickly leave Hertfordshire, leaving the field free to Wickham.

Wickham confides

[edit]Burning to know the reasons for his and Darcy's attitude when they were face to face, and blinded by her prejudice against Darcy, Elizabeth is not alerted by the impropriety that Wickham demonstrated by using the first opportunity to address the subject himself; she does not realize the skill with which he manipulates her through his hesitation and reticence.[25] On the contrary she looks forward to his sparkling conversation, not realising her imprudence in believing a man who is a tricky conversationalist.[13] Relying totally on his good looks, she accepts without question, without even considering to check it, his version of the story.[26] She sympathises fully with his misfortunes, when he obligingly describes the unfair treatment to which he was subjected: Darcy had, through pure jealousy, refused to respect the will of his late father who had promised him the enjoyment of ecclesiastical property belonging to the family, forcing him to enlist in the militia to live.[n 8] Although Wickham states that out of respect to his godfather, he cannot denounce Darcy, he does so, feeding into Elizabeth's prejudices about Darcy.[27]

He lies with skill, especially by omission, taking care not to mention his own faults, and remains close enough to the truth to deceive Elizabeth: nothing he says about the behaviour of Darcy is fundamentally wrong, but it is a warped presentation, "pure verbal invention" according to Tony Tanner.[28] Darcy's generosity, attention to his farmers, and affection for his sister, are presented as the work of a calculating mind with a terrible aristocratic pride. Thus, in the context of Meryton, without his past and his family being known, Wickham's lies are readily believed, and he is left to indulge in his weakness for gambling and debauchery.[29] He is protected by the mask of his fine manners and the certainty that Darcy, anxious to preserve the reputation of his younger sister, would not stoop to denounce him.[5]

Revelations of Darcy

[edit]In the long letter that Darcy presents to her in Rosings Park Elizabeth discovers the true past of Wickham and can begin to sort out the truth from the lies.[30]

She thus recognises that she failed in judgment, "because his attitude, his voice, his manners had established him straightaway as in possession of all qualities". She admits to being at first mistaken by the appearance of righteousness and an air of distinction.[n 9] She notices an "affectation" and an "idle and frivolous gallantry" in Wickham's manners after being informed by Darcy's letter.[31]

George Wickham was the son of an estate manager for Mr. Darcy Senior, and George Wickham was the godson of Mr. Darcy Senior, who raised him practically like a second son, both in recognition of his father's work and loyalty and by affection for this boy with "charming manners". Because he wanted to secure Wickham's future, his godfather paid for his studies in college and then at Cambridge.[n 10] By giving him the ability to enter religious orders and by granting him the valuable living of a curacy dependent on Pemberley (Kympton), he would have guaranteed Wickham a most honourable social position. Not at all attracted by the clerical profession, to the great relief of Darcy, Wickham preferred to claim a final settlement of £3,000 at the death of his godfather, in lieu of the Living, on top of an inheritance of an additional £1,000 also left to him by Darcy Sr.—an amount of £4,000 in total, which would have provided Wickham with a living allowance of £200 per annum, IF he hadn't squandered it.

Once this money was squandered Darcy refused him further help, so Darcy supposed that he sought revenge and financial enrichment by taking advantage of Georgiana Darcy's stay in Ramsgate to seduce her, hoping to steal her away and marry her, getting his hands on the young girl's £30,000 dowry.[32] His attempt to seduce Georgiana was facilitated by their childhood friendship (to which Darcy alluded when he described Wickham to Elizabeth) and the relative isolation of the shy adolescent (she was only fifteen years old) without a mother to chaperone her at the seaside town,[19] and by having her companion, Mrs. Young, helping him.

Several scandals

[edit]

He is a good-for-nothing and a scoundrel who shows two forms of evil.[34] He is "imprudent and extravagant" as Colonel Forster finally discovered, which meant, in less diplomatic language, that he had love affairs and piled up debts, especially gambling debts.[35] It is discovered at the time of his elopement with Lydia that Wickham has not maintained any long friendships before he entered the militia at the urging of Denny. This is presented in the novel as having been a sign of his bad character, and Fulford states that Wickham uses the prestige of the militia and the anonymity it provides to run away from his debts.[22] He searched desperately for a financially advantageous marriage:[36] in Meryton, Wickham openly courted Mary King from the moment she inherited 10,000 pounds, but her uncle took her to Liverpool.[37] Tongues loosened to reveal other misadventures once Lydia's absence became known: "He was declared to be in debt to every tradesman in the place, and his intrigues, all honoured with the title of seduction, had been extended into every tradesman's family".[38]

Lydia, at fifteen, Georgiana's age when he tried to take her away, falls madly in love while they are in Brighton, to the point of agreeing to accompany him when he flees the regiment for not paying his debts of honour.[n 11] She refuses to leave him, insensitive to the collateral damage the scandal will cause to her family,[39] but he only marries her in desperation, negotiating the terms with Darcy who uses his connections and his fortune to procure Wickham a position, and save Lydia's respectability, allying himself with Mr Gardiner for the occasion.[40] The reactions of the Bennet family are mixed: Mrs Bennet, relieved to see a first daughter duly married, and delighted that it is her favourite daughter, welcomes the young couple with affection after the wedding, sorry to see them go to rejoin the Garrison at Newcastle. Jane blushed in confusion and Mr Bennet ironically claims to be "enormously proud" of a son-in-law so shameless and cynical: "He simpers, and smirks, and makes love to us all."[41]

Elizabeth is "disgusted" to see Lydia and him so comfortable and "promises, in the future, never to set limits on the impudence of an impudent man".[42] According to Claire Tomalin, this is partially due to a lingering jealousy of Elizabeth towards Lydia for marrying Wickham.[7] Wickham's final scene in the novel is "presented as an interruption" – Woloch notes that Elizabeth tries to walk to the house quickly in order to get rid of him, and that she "hoped she had silenced him". According to Woloch, the narrator suggests that Wickham and Elizabeth "never speak seriously again" after this conversation.[43] In this conversation, Wickham tries to discern what Elizabeth now knows about him with some "careful probing", and she responds with "some gentle teasing", which Mai interprets as showing the value of forgiveness.[33] Elizabeth is no longer fooled, not by his beautiful rhetoric nor by his engaging ways. Elizabeth and Jane, who are the only ones to know the whole truth of Wickham's character, continue their financial support of their sister, and Darcy helps Wickham in his career (as he had promised his father, and for the sake of his wife), but the doors of Pemberley remain definitely closed to him.[44]

Analysis

[edit]An image of a rake

[edit]

In the actantial scheme Wickham plays the role of the opponent. He represents the traditional figure of the debauched and depraved libertine from novels of the eighteenth century.[40] The figure of the bad boy, who is dangerous and a bit too enticing, from whom the heroine must learn to stay away, is presented with more vivacity than the hero who is honest and a real gentleman.[45] Wickham is no exception to the rule: he has charm and immediately captivates by his apparent frankness and friendly ease.[46] But he is the most dissolute and the most cynical of all the seducers described by Jane Austen, and he uses his good looks and good education to create an illusion.[47] He has defects that are much more serious than those of the bad boys in the other novels:[48] a formidable manipulator of language,[13] he is also the only one who recklessly plays a big game,[49] the only one who slanders with such impudence;[19] and things go much worse for him than for them who, on the contrary, do not end up banished from good society.[13]

He is also the only one of lower social status. In this regard, Jane Austen contrasts the judgement of Elizabeth Bennet to that of Caroline Bingley, imbued with rank and fortune.[n 12] Miss Bingley's prejudice against Wickham, in her ignorance of the inside story, leans mainly on the fact that he is a commoner ("Considering where he comes from, you cannot expect much better"), when Elizabeth shows a greatness of spirit in refusing to tie the value of a person to his social position: "His guilt and his descent appear by your account to be the same (...) for I have heard you accuse him of nothing worse than of being the son of Mr, Darcy's steward". Darcy himself refuses to tie Wickham's origin to his conduct, since he considers, in his letter to Elizabeth, that Wickham's father was "a very respectable man, who had the responsibility of the entire Pemberley estate for years" and admirably performed his duties.[50] By using the snobbish Miss Bingley to warn Elizabeth, and the naive Jane in Darcy's defense, Austen subtly prejudices the reader's mind in favour of Wickham.[51]

Robert Markley argues that Wickham's seduction spree is a way to revenge himself on the gentlemanly society that he has the education, but not the funds, to access.[15] The narrator uses Wickham to argue against the idea of love at first sight,[52] and Hall states that this allows Elizabeth to consider the attractive reliability of the "boy next door", Darcy.[13] Alex Woloch discusses Wickham as a foil to Mr. Collins in terms of their being unworthy suitors for Elizabeth – while Mr. Collins offers financial security without love, Wickham offers sexual fulfilment without stability.[53]

A hidden character

[edit]

The omniscient narrator reveals nothing of the youth or the true nature of Wickham. The reader knows him only through what he says about himself and what is said about him, but only later in the story, by characters who knew him before: Darcy (at Rosings Park), and Mrs. Reynolds (at Pemberley). It is therefore difficult to get a fair idea of a character so difficult to define. If the Bingley family (who had never met him before their arrival in Hertfordshire) are only aware of the little Darcy has told them, Mrs. Reynolds, the housekeeper of Pemberley, has known Darcy and Wickham from infancy.[54] She can confirm that he was raised at Pemberley at the expense of Mr. Darcy Senior, and knows that he is in the army, but fears that he has turned out badly: "I am afraid he has turned out very wild".[55]

At most, the narrator gives the reader a subtle warning by some facial expressions, some slight pauses (marked by dashes) some hesitations in his conversation. In this way, on the evening of their first meeting, Wickham asks Elizabeth, in a slightly hesitating manner, how long Darcy has been in Hertfordshire, then, "after a short pause", Elizabeth vividly assures him that all Meryton is "disgusted by his pride" and that no one has anything good to say about him, he begins to disclose his confidences to a partner who is all ears.[56] Later, hearing Collins quote Lady Catherine, and "after having observed her for a moment," he asks Elizabeth if she is closely linked to the De Bourgh family. She is convinced that what he says is true because he looks so honest, and that is what justifies and reinforces her dislike for Darcy.[56] For Matt Brumit, when Wickham avoids the whist card game and sits with Elizabeth and Lydia to play lotteries, Wickham may be attempting to hide his gambling, rather than the sign of interest Elizabeth sees it as.[57]

It is only after the revelations of Darcy that Wickham's true character is "unmasked" for Elizabeth.[56] The reader, going back and forth with her, becomes aware of his prudent way of "testing the waters" and gauging the feelings of others, addressing himself to a cynical manipulation of his interlocutors, subtly hiding the truth by deliberate omissions and practicing safe slander (he confides only to Elizabeth while Darcy is at Netherfield, but makes his version of the facts public as soon as Darcy is gone). It is only "a posteriori" that the irony in the vocabulary of emotion he uses is discovered: "I can never be in company with this Mr. Darcy without being grieved to the soul by a thousand tender recollections".[58] Darcy evokes, in him, "his resentment in proportion to the distress of his financial situation and the violence of his reproaches". For Richard Jenkyns, Wickham's deceptiveness is the "pivot upon which the entire plot turns". Jenkyns discusses how Claire Tomalin regards Wickham as frivolous rather than a true villain, but Jenkyns regards this as being further evidence of Wickham being a great conman. Jenkyns points out, in defending Austen's characterisation of Wickham, that the only account of the seduction of Georgiana is given by Darcy.[59] Susan Morgan regards Wickham as being designed by Austen to be a stock villain in both his "false face as a charming young man and in his true face as the fortune hunter" – even the kind-hearted Jane cannot fail to understand that Wickham's intentions towards Lydia are dishonourable when she discovers Wickham is "a gamester!".[11]

Wickham, whose speech is full of duplicity and is skilled at making white look black [60] has certainly read with profit Lord Chesterfield's Letters to His Son, full of pragmatic, but also quite Machiavellian advice, to appear a true gentleman in society.[5]

Appearance and reality

[edit]Jane Austen uses nearly the same words to describe Charles Bingley and George Wickham:[61] both are likable, charming, cheerful, have easy manners, and above all, have the air of a gentleman. But Wickham, to whom Austen gives more engaging manners if it is possible than to Bingley, only has the appearance of a gentleman – not the behaviour – as Elizabeth will point out bitterly afterward. Bingley is impressionable, weak even, without much knowledge of himself,[62] but he is simple and honest, while Wickham is a hypocrite and a true villain who hides his "lack of principles" and his "vicious tendencies" under his likable airs.[61]

The character defect that the narrator attacks most strongly in Pride and Prejudice is reliance on first impressions and judging only on the face and general appearance.[63] Jane Austen frequently used the word "appearance" when describing Wickham so as to emphasize that Elizabeth can see only the surface of the character.[64] Wickham is assumed to be honest because he is handsome and his manners are charming.[61] Elizabeth, who told Jane that "sincerity can be read on his face", and Mrs. Gardiner that he is "beyond all comparison, the most agreeable man I ever saw," which implies she is relying on his appearance to show his character,[65] acknowledges, after having read what Darcy reveals of Wickham, that she had never thought of going beyond the appearance and to analyse his "real character".[66] Thus, the narrator reveals Elizabeth has been taken in by the surface appearance of Wickham.[67]

As to the opinion of the inhabitants of Meryton, the narrator shows with some irony that it is unreliable and unpredictable:[68] if Wickham is "universally appreciated" at the beginning, he is then considered, with the same exaggeration, as the most evil (wickedest) man in the world, and each one openly affirms that they were always highly suspicious of his apparent virtue: "had always distrusted the appearance of his goodness".[38]

Two young people of Derbyshire

[edit]Two foils

[edit]Jane Austen invites the reader to compare the evolution of the "two gentlemen of Derbyshire", Darcy and Wickham, who are "born in the same parish, within the same park" and are "nearly the same age". They are therefore childhood companions ("the companion of my youth" wrote Darcy), that the behaviour of Wickham towards Georgiana has transformed into enemies and at the meeting of Elizabeth into rivals.[4] Wickham acts as a foil to Darcy – Austen uses the comparison between the two characters to contrast them and provide insights into each of the men.[5] Raised at Pemberley (an almost perfect and ideal place) and pampered by his godfather, the former owner, Wickham knew Darcy very well. George Wickham was the son of the steward, he probably always felt envy and jealousy towards the heir. Taking after his spendthrift mother, Wickham, instead of taking the virtuous and honorable way offered to him, rejected the moral rules that governed the estate and the behaviour of its successive owners, keeping only the exterior of a gentleman, not the behaviour.[29]

Winter life in Meryton, in the midst of idle officers, generally sons of good families who relieved their boredom by breaking the hearts of romantic young girls, and incurring debts that frequent trips allowed them to avoid paying;[69] the opportunities to participate in balls, assemblies, and evening soirées organized by the "four-and-twenty families" who were relatively rich, was better suited to his libertine tastes.[n 13] Wickham's irresponsible elopement with Lydia inspires Elizabeth to confide in Darcy,[71] setting the stage for Darcy to demonstrate that he now feels responsible for Wickham's continued bad behaviour by his silence – if he had made Wickham's bad character known, Lydia would have been safe. Darcy chooses to involve himself in arranging Lydia's marriage, despite the risk to his own reputation.[20]

As Lydia Bennet, wasteful and morally uncontrollable, embodies the dark side of Elizabeth, so Wickham appears as the double negative of Darcy: he takes liberties with the truth (Darcy claims to have a horror of lying),[n 14] he has sentimental adventures, accumulates a dark slate of debts with the merchants, and, most importantly, is an unrepentant gambler.[72] The couple that is formed in the outcome with Lydia, writes Marie-Laure-Massei Chamayou, "therefore represents the opposite sulfurous and Dionysian side"[n 15] to the solar couple who are Darcy and Elizabeth.[73]

A moral outcome

[edit]The fact that Wickham and Darcy are both attracted to Elizabeth is important for the moral sensibility of the Bildungsroman: Elizabeth must not be wrong and choose the wrong suitor. The parallels between the journey of the two young men from Derbyshire and the two Bennet daughters who are both lively and cheerful, who love to laugh and find themselves attracted by Wickham end in a very moral fashion:[74] Darcy, the honest man, weds Elizabeth and takes her to Pemberley. Wickham, the rakehell and unlucky gambler, after having courted Elizabeth for a time, is forced to marry the foolish Lydia and sees himself exiled far from Pemberley.[4]

In trying to seduce Georgiana and by fleeing with Lydia, he defied a moral edict and social convention,[75] that Jane Austen whose "view of the world was through the Rectory window"[76] neither could nor would excuse: while she offers her heroes a happy future based on affection, mutual esteem, and a controlled sexuality;[74] Austen forces Wickham to marry Lydia,[77] whom he quickly ceases to love.[78] Although he had almost seduced Georgiana Darcy, and then paid attention to Mary King with her 10,000 pounds a year, Wickham runs off with Lydia and is bribed to marry her. It seems that he often runs away from his marriage to "enjoy himself in London or Bath", which critic Susannah Fullerton regards as being what Wickham deserves.[79] But he does not have the stature of his predecessor, Lovelace,[80] nor is he as thorough a villain.[79] His rank of ensign in the regular army was the lowest and could be held by boys of 15, which Breihan and Caplan see as a sign of Darcy feeling that "enough was enough!"[81] Wickham's career path in the North, where he might at any point be drawn into war, may reflect a desire for atonement and honest service.[82]

Portrayal in adaptations

[edit]Pride and Prejudice, 1940

[edit]In the film of 1940, as in screwball comedies in general, the psychology of the characters is not investigated,[83] and Wickham is a very minor and superficial character. Elizabeth has learned that Darcy has initially refused to invite her to dance because she is not in his social class, and that he has committed an injustice towards Wickham: consequently she refused to dance with him at the Meryton Ball when he finally came to invite her, accepting, rather, to waltz with Wickham (Edward Ashley-Cooper), but there is no later relationship between Wickham and Elizabeth. She is persuaded that Darcy has rejected the friendship of Wickham only because he is "a poor man of little importance".[84]

Shortly after having been spurned by Elizabeth at Rosings, Darcy comes to Longbourn to explain his attitude towards Wickham and tell her of the attempted abduction of his sister. Then learning of Lydia's flight, he offers his help and disappears.[83] It is a letter which puts an end to the scandal by informing the Bennets that Lydia and Wickham are married. It is followed by the rapid return of the two lovebirds in a beautiful horse-drawn carriage, and Lydia speaks with assurance about the rich inheritance her husband has received.[85]

Television adaptations for the BBC (1980 and 1995)

[edit]They give much more attention to Wickham.[83] In both, Elizabeth has a lot of sympathy for Wickham, perhaps more in the 1980 version where he is played by the blond Peter Settelen. He is shown playing croquet with Elizabeth who speaks fondly of Jane, who has just received a letter from Caroline, expressing the hope that her brother will marry Miss Darcy. Wickham says that being loved by Elizabeth would be a privilege because of her loyalty towards those for whom she cares. A mutual attraction is more clearly seen in this adaptation than the 1995 adaptation.[86] When Mrs. Gardiner warns against reckless commitments, as in the novel, her niece reassures her that she is not in love with Wickham, but adds, nonetheless, that the lack of money rarely prevents young people from falling in love. She calms her sisters, much more affected than herself by Wickham's courtship of Mary King, pointing out to them that young people must also have enough money to live on. Lydia, by contrast, seems to be already very interested in Wickham and tries to get his attention.[87]

The Pride and Prejudice of 1995 further highlights the two-faced nature of the character, played by Adrian Lukis, a tall dark haired actor who was by turns smiling, insolent, or menacing. He appears as a much darker character than in the previous version, which may explain why the attraction he exerts over Elizabeth is less emphasized than in the 1980 series.[88] Elizabeth takes a cheerful tone in congratulating him on his forthcoming marriage to Mary King, noting that, "handsome young men must also have enough to live on".[86] The lack of principles and greed which Darcy's letter accuses him of are subject to short scenes with Darcy's letter read in a voiceover, which has the effect of emphasising Wickham's "flawed character".[87] Wickham prudently asks Mrs. Gardiner if she personally knows the Darcy family, and his distress at the knowledge that Elizabeth has met Colonel Fitzwilliam at Rosings, and that her opinion of Darcy has changed is visible to the audience. Later, Mrs. Philips relates to Mrs. Bennet his gambling debts, his seductions, and his unpaid bills with merchants. Closely monitored by Darcy, and under the stern gaze of Gardiner during the wedding ceremony, he then cuts a fine figure at Longbourn, where his conversation with Elizabeth (who has just read the letter from her aunt revealing the key role played by Darcy in bringing about the marriage) is repeated almost word for word, showing him silenced finally. His life with Lydia is revealed in only a short montage shown during the double wedding of Jane and Elizabeth. When the officiating minister says that marriage is a remedy against sin and fornication,[89] Lydia basks on the conjugal bed while Wickham looks on with boredom.[90]

Pride and Prejudice, 2005

[edit]

In the 2005 film, Wickham plays a very small role,[91] but Rupert Friend plays a dark and disturbing Wickham, even brutal when he pushes Lydia into the carriage as she bids a tearful farewell on permanently leaving Longbourn. He has the "reptilian charm of a handsome sociopath", which suggests an unhappy marriage.[92]

Meetings with Elizabeth are reduced to two short scenes, a brief discussion in a shop about ribbons, and another, near the river, which, however, is sufficient for him to give Darcy a bad name.[91] But if the complex relationships that existed with Elizabeth in the novel have been removed, the strong physical presence of Rupert Friend has sexual connotations and Wickham plays the role of a stumbling block in the relationship between Darcy and Elizabeth. First, at the Netherfield Ball when Elizabeth accuses Darcy of having maltreated Wickham, and especially during the scene of the first marriage proposal where Darcy has a strong jealous reaction when Elizabeth again brings up Wickham's name. This creates a strong sexual tension between the two young people and leads them to almost kiss.[92]

Remakes

[edit]In Lost in Austen, however, the entire plot of Pride and Prejudice evolves in a different direction. Wickham (Tom Riley) is depicted as an ambiguous character, but very positive and charming, who initiates Amanda Price into the customs of Georgian society. He also saves her from being engaged to Mr. Collins by spreading the rumour that Mr. Price was a fishmonger.[93] He does not attempt to take Georgiana and helps to find Lydia with Mr. Bingley.

In the 1996 novel Bridget Jones's Diary, and its film adaptation released in 2001, Helen Fielding was inspired by Wickham to create Daniel Cleaver, the womanising, cowardly boss of Bridget Jones, the rival of Mark Darcy.

In the modernised American web series of 2012–2013, The Lizzie Bennet Diaries, Wickham is the coach of a university swim team and played by Wes Aderhold.[94] In this version, Wickham is depicted as being abusive towards Lydia, manipulating her into recording a sex tape.[95]

Wickham plays a central role in the 2022 Claudia Gray novel, The Murder of Mr. Wickham.[96]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Deirdre Le Faye thinks the militia described in Pride and Prejudice is inspired by the Derbyshire volunteers, who spent the winter of 1794–1795 in Hertfordshire. (Deirdre Le Faye 2003, p. 189)

- ^ According to Carole Moses, the narrator is quite happy to directly pass judgement on some characters, such as Mrs. Bennet and Mr. Collins. Moses states that Austen does not provide us with a means of judging Wickham and Darcy, and so we rely on Elizabeth's assessment. Moses argues that in this way, Austen tricks the reader into making the same mistake as Elizabeth does in their first impressions of Wickham and Darcy.[14]

- ^ Wickham finds a means "unconnected with his general powers" (Chapter 25) to beguile Mrs Gardiner, by referring to Pemberley and Lambton and giving her news of their common acquaintances. Jane Austen gives reality (Pierre Goubert 1975, p. 34 and 40) to the project of the Gardiners by visiting this particular part of Derbyshire.

- ^ As a militiaman, Wickham would probably earn a salary of less than 100 pounds per year.[15] His wage is "barely enough" to support himself, let alone a wife and family, and he does not have much opportunity to get better paying employment.[16]

- ^ Wickham's introduction so soon after Mr. Collins, who is overawed by his patroness's money and title, is stated by Sherry as providing proof that only characters who do not idolise rank and money can be sensible.[20]

- ^ It was a pressing issue at the time — around the time when Austen wrote First Impressions, the first draft of Pride and Prejudice, large rafts were being constructed in Brest and Calais, each armed with guns and capable of carrying thousands of men (Deirdre Le Faye 2002, p. 155-156) to invade England, as evidenced by a letter from Eliza Hancock dated February 16, 1798.(Deirdre Le Faye 2002, p. 152-153)

- ^ Jane Austen knew how militias functioned through her brother Henry, who served in the militia of Oxfordshire between 1793 and 1801, first as a lieutenant and then captain, steward, warrant officer from 1797 to 1801, when he resigned to become a banker and military agent. Henry married Eliza Hancock, his cousin on 31 December 1797. She refers, in a letter to her friend Philly Walter to garrison life and these fine young men, "of whom I wish You could judge in Person for there are some with whom I think You would not dislike a flirtation" and specifies how she (in all honour) admired the dashing Captain Tilson: "Captn. Tilson is remarkably handsome".(Deirdre Le Faye 2002, p. 154) The militiamen would have been recognised by Austen's readers as idle because the feared invasion never came, leaving them with time on their hands to be "disruptive" (Tanner, 1975, p.104)

- ^ Margie Burns thinks Wickham's quickness to slander Darcy to Elizabeth is more than a way to protect himself from improbable accusations (he knows Darcy enough not to fear Darcy's sharing of the scandal). To Burns, it is a subtle form of revenge because Wickham immediately saw that Darcy was interested in Elizabeth.[19]

- ^ Pierre Goubert on page 15 of the Preface to the classic Folio edition (ISBN 9782070338665) indicates that the change from the title First Impressions to Pride and Prejudice allows the author to show that vanity and pride are essential in forming a first judgment, and how they impede the spread of information and prevent observation.

- ^ Darcy said that George Wickham's father could not afford to pay for his son's studies because of the "extravagance of his wife". (Chapter 35)

- ^ Margie Burns highlights the similarities between the situations of Georgiana Darcy and Lydia Bennet: their youth, their naivety, their presence in a seaside resort, and the lack of a serious chaperone, making them easy prey.[19]

- ^ Although Caroline Bingley, through her haughty and condescending behaviour prefers to forget that she is herself the daughter of a merchant. (Massei-Chamayou 2012, p. 173)

- ^ Jane Austen knew the operation of the Territorial Army through her brother Henry, who had joined the militia of Oxford in 1793 and advanced in rank until 1801, when he resigned.[70]

- ^ "But disguise of every sort is my abhorrence" (Chapter 34)

- ^ Original quote: « représente donc l'envers sulfureux et dionysiaque »

References

[edit]- ^ Margaret Anne Doody, "Reading", The Jane Austen companion, Macmillan, 1986 ISBN 978-0-02-545540-5, p. 358-362

- ^ a b Jo Alyson Parker (1991), "Pride and Prejudice: Jane Austen's Double Inheritance Plot", in Herbert Grabes (ed.), Yearbook of research in English and American Literature, pp. 173–175, ISBN 978-3-8233-4161-1

- ^ Ian Littlewood (1998), Jane Austen: critical assessments, vol. 2, pp. 183–184, ISBN 978-1-873403-29-7

- ^ a b c Laurie Kaplan (Winter 2005). "The Two Gentlemen of Derbyshire: Nature vs. Nurture". Jasna.org. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Jennifer Preston Wilson (Winter 2004). ""One has got all the goodness, and the other all the appearance of it": The Development of Darcy in Pride and Prejudice". Jasna.org. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Baker, William (2008). Critical companion to Jane Austen a literary reference to her life and work. New York: Facts On File. p. 404. ISBN 978-1-4381-0849-0.

- ^ a b Tomalin, Claire (1997). Jane Austen : a life (1 ed.). London: Viking. pp. 164–165. ISBN 0-670-86528-1.

- ^ Craig, Sheryl (Winter 2015). "Jane and the Master Spy". Persuasions On-Line. 36 (1).

- ^ Lydia Martin 2007, p. 70

- ^ a b Austen, Jane (1813). . – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b Morgan, Susan (August 1975). "Intelligence in "Pride and Prejudice"". Modern Philology. 73 (1): 54–68. doi:10.1086/390617. JSTOR 436104. S2CID 162238146.

- ^ Austen, Jane (1813). . . p. 112 – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b c d e Lynda A. Hall (1996). "Jane Austen's Attractive Rogues" (PDF). Jasna.org. Retrieved 2015-05-27.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Carole Moses. "Jane Austen and Elizabeth Bennet: The Limits of Irony" (PDF). Persuasions. JASNA. Retrieved 2015-05-30.

- ^ a b Markley, Robert (2013). "The economic context". In Todd, Janet (ed.). The Cambridge companion to Pride and prejudice. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 93–95. ISBN 978-1-107-01015-4.

- ^ Austen, Jane (2012). Shapard, David M. (ed.). The annotated Pride and prejudice (Rev. and expanded ed.). New York: Anchor Books. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-307-95100-7.

- ^ Austen, Jane (1813). . – via Wikisource.

- ^ Austen, Jane (2012). Shapard, David M. (ed.). The annotated Pride and prejudice (Rev. and expanded ed.). New York: Anchor Books. p. 439. ISBN 978-0-307-95100-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Burns, Margie (2007). "George and Georgiana: Symmetries and antitheses in Pride and Prejudice" (PDF). Persuasions, the Jane Austen Journal. 29: 227–233. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ a b Sherry, James (1979). "Pride and Prejudice: The Limits of Society". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 19 (4): 609–622. doi:10.2307/450251. JSTOR 450251.

- ^ Deirdre Le Faye 2002, p. 153

- ^ a b Fulford, Tim (September 2002). "Sighing for a Soldier: Jane Austen and Military Pride and Prejudice" (PDF). Nineteenth-Century Literature. 57 (2): 153–178. doi:10.1525/ncl.2002.57.2.153.

- ^ Deirdre Le Faye 2003, p. 189

- ^ Austen, Jane (1853). . – via Wikisource.

- ^ Elizabeth Honor Wilder (2006). "Cameo: Reserve and Revelation in Pride and Prejudice". Jasna.org. Retrieved 2015-05-10.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hardy, John P. (1984). Jane Austen's heroines : intimacy in human relationships (1. publ. ed.). London: Routledge & K. Paul. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-7102-0334-2.

- ^ Fullerton, Susannah (2013). Celebrating Pride and Prejudice : 200 years of Jane Austen's masterpiece. Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-7603-4436-1.

- ^ Tony Tanner 1975, p. 112

- ^ a b Opdahl, Keith M. (2002). Emotion as meaning : the literary case for how we imagine. Lewisburg (Pa.): Bucknell University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-8387-5521-1.

- ^ Laura R. Rowe (2005). "Beyond Drawing-Room Conversation: Letters in Pride and Prejudice". Jasna.org. Retrieved 2015-05-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hardy, John Philips (2012). Jane Austen's Heroines: Intimacy in Human Relationships. Routledge. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-136-68180-6.

- ^ Austen, Jane (1813). . – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b Robert Mai (Winter 2014). "To Forgive Is Divine—and Practical, Too". Persuasions On-Line. 35 (1). Jasna.org. Retrieved 2015-05-28.

- ^ Carroll, Joseph (2004). Literary Darwinism : evolution, human nature and literature. New York: Routledge. pp. 206, 211. ISBN 978-0-415-97013-6.

- ^ Austen, Jane (1813). . – via Wikisource.

- ^ Goode, Ruth (1984). Jane Austen's Pride and prejudice. Woodbury, N.Y.: Barron's. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9780812034370.

- ^ Doody, Margaret (2015). Jane Austen's Names: Riddles, Persons, Places. University of Chicago Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-226-15783-2.

- ^ a b Austen, Jane (1813). . – via Wikisource.

- ^ Allen, Dennis W. (1985). "No Love for Lydia: The Fate of Desire in Pride and Prejudice". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 27 (4): 425–443. JSTOR 40754783.

- ^ a b Vivien Jones, Pride and Prejudice (introduction), Penguin Classics, 2003, p. xxxiv. ISBN 978-0-14-143951-8

- ^ Austen, Jane (1813). . – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b Austen, Jane (1813). . – via Wikisource.

- ^ Woloch, Alex (2003). The one vs. the many minor characters and the space of the protagonist in the novel. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-4008-2575-2.

- ^ Vivien Jones, Pride and Prejudice (introduction), Penguin Classics, 2003, p. xxx ISBN 978-0-14-143951-8

- ^ Lydia Martin 2007, p. 56

- ^ Pierre Goubert 1975, p. 128

- ^ Massei-Chamayou (p.329)

- ^ Massei-Chamayou (p.345)

- ^ Massei-Chamayou (p.346)

- ^ Pierre Goubert 1975, p. 311

- ^ Berger, Carole (Autumn 1975). "The Rake and the Reader in Jane Austen's Novels". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 15 (4): 531–544. doi:10.2307/450009. JSTOR 450009.

- ^ Sorbo, Marie (2014). Irony and Idyll: Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice and Mansfield Park on Screen. Rodopi. p. 64. ISBN 9789401210898.

- ^ Woloch, Alex (2003). "Narrative Asymmetry in Pride and Prejudice". The one vs. the many minor characters and the space of the protagonist in the novel. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-1-4008-2575-2.

- ^ Tony Tanner 1975, p. 119

- ^ Austen, Jane (1813). . – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b c Tony Tanner 1975, p. 116

- ^ M. W. Brumit (Winter 2013). ""[T]hey both like Vingt-un better than Commerce": Characterization and Card Games in Pride and Prejudice". Jasna.org. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Pierre Goubert 1975, p. 73

- ^ Jenkyns, Richard (2007). A fine brush on ivory : an appreciation of Jane Austen. Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 26–29. ISBN 978-0-19-921099-2.

- ^ Tony Tanner 1975, p.112

- ^ a b c Auerbach, Emily (2006). Searching for Jane Austen. Madison, Wis.: Univ. of Wisconsin Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-299-20184-5.

- ^ Reeta Sahney 1990, p. 36

- ^ Pride and Prejudice, classic folio presented by Pierre Goubert, p. 11

- ^ Stovel, Bruce; Gregg, Lynn Weinlos, eds. (2002). The talk in Jane Austen. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-88864-374-2.

- ^ Auerbach, p.153

- ^ Austen, Jane (1853). . – via Wikisource.

- ^ Sorbo, Marie (2014). Irony and Idyll: Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice and Mansfield Park on Screen. Rodopi. p. 38. ISBN 9789401210898.

- ^ Tony Tanner 1975, p. 111

- ^ Pride and Prejudice, classic folio, presented by Pierre Goubert, p. 22

- ^ J. David Grey (1984). "HENRY AUSTEN: JANE AUSTEN'S "PERPETUAL SUNSHINE"". Jasna.org. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bruce Stovel (1989). "Secrets, Silence, and Surprise in Pride and Prejudice". Persuasions. Jasna.org. Retrieved 2015-05-30.

- ^ Massei-Chamayou 2012, p. 146-147

- ^ Massei-Chamayou 2012, p. 147

- ^ a b Elvira Casal (Winter 2001). "Laughing at Mr. Darcy: Wit and Sexuality in Pride and Prejudice". Jasna.org. Retrieved 2015-05-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Reeta Sahney 1990, p. 35

- ^ Reeta Sahney 1990, p. xiii

- ^ Reeta Sahney 1990, p. 9

- ^ Austen, Jane (1853). . – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b Fullerton, Susannah (2013). Celebrating Pride and Prejudice: 200 years of Jane Austen's masterpiece. Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-0-7603-4436-1.

- ^ Tony Tanner 1975, p. 95.

- ^ Breihan, John; Caplan, Clive (1992). "Jane Austen and the Militia" (PDF). Persuasions. JASNA. Retrieved 2015-06-08.

- ^ Tandon, Bahrat (2013). "The historical background". In Todd, Janet (ed.). The Cambridge companion to Pride and prejudice. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-1-107-01015-4.

- ^ a b c Sue Parrill 2002, p. 54

- ^ Lydia Martin 2007, p. 101

- ^ Lydia Martin 2007, p. 103

- ^ a b Sue Parrill 2002, p. 71

- ^ a b Sue Parrill 2002, p. 72

- ^ Lydia Martin 2007, p. 106

- ^ Lydia Martin 2007, p. 110

- ^ Sorbo, Marie (2014). Irony and Idyll: Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice and Mansfield Park on Screen. Rodopi. pp. 144–145. ISBN 9789401210898.

- ^ a b Jen Camden (Summer 2007). "Sex and the Scullery: The New Pride & Prejudice". Jasna.org. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Catherine Stewart-Beer (Summer 2007). "Style over Substance? Pride & Prejudice (2005) Proves Itself a Film for Our Time". Jasna.org. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Laurie Kaplan. ""Completely without Sense": Lost in Austen" (PDF). JASNA. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "George Wickham". Pemberley Digital. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

- ^ Lori Halvorsen Zerne (Winter 2013). "Ideology in The Lizzie Bennet Diaries". Jasna.org. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The Murder of Mr. Wickham". Vintage Books. Retrieved 2022-06-11.

Bibliography

[edit]Primary source bibliography

[edit]- Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice, R. Bentley, 1853, 340 p.

- Jane Austen, "Pride and Prejudice," on The Republic of Pemberley

- Austen, Jane (1853). – via Wikisource.

- Austen, Jane (2007). Goubert, Pierre (ed.). Orgueil et préjugés (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 9782070338665.

Secondary source bibliography

[edit]- Marie-Laure Massei-Chamayou, La Représentation de l'argent dans les romans de Jane Austen: L'être et l'avoir, [Representation of Money in Jane Austen's Novels : To Be and To Have], Paris, L'Harmattan, edited collection "Des idées et des femmes" ["Ideas and Women,"] 2012, 410 p. ISBN 978-2-296-99341-9

- Lydia Martin, Les adaptations à l'écran des romans de Jane Austen: esthétique et idéologie, [Screen Adaptations of the Novels of Jane Austen: Aesthetics and Ideology,] L'Harmattan Edition, 2007, 270 p. ISBN 9782296039018

- Emily Auerbach, Searching for Jane Austen, Madison, The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004 ISBN 978-0-299-20184-5

- Deirdre Le Faye, Jane Austen: The World of Her Novels, London, Frances Lincolv, 2003 ISBN 978-0-7112-2278-6

- Deirdre Le Faye, Jane Austen's outlandish cousin: the life and letters of Eliza de Feuillide, British Library, 2002, 192 p. ISBN 978-0-7123-4762-4

- Sue Parrill, Jane Austen on film and television: a critical study of the adaptations, McFarland, 2002, 221 p. ISBN 978-0-7864-1349-2

- Reeta Sahney, Jane Austen's heroes and other male characters, Abhinav Publications, 1990 ISBN 9788170172710

- John P. Hardy, Jane Austen's Heroines: Intimacy in human relationships, London, Routledge and Paul Kegan, 1984 ISBN 978-0-7102-0334-2

- Tony Tanner, Jane Austen, Harvard University Press, 1975, 291 p. ISBN 978-0-674-47174-0, "Knowledge and Opinions: 'Pride and Prejudice'" (reissue 1986)

- Pierre Goubert, Jane Austen : étude psychologique de la romancière [Jane Austen: a psychological study of the novelist], PUF (Publications of the University of Rouen), 1975