Omak, Washington

Omak | |

|---|---|

| City of Omak | |

| |

| Motto: Heart of the Okanogan | |

Location of Omak in Okanogan County, Washington | |

| Coordinates: 48°24′45″N 119°32′15″W / 48.41250°N 119.53750°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Okanogan |

| Established | January 1, 1907 |

| Incorporated | February 11, 1911 |

| Founded by | Ben Ross |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Cindy Gagne |

| • Governing body | Omak City Council |

| Area | |

• City | 3.94 sq mi (10.21 km2) |

| • Land | 3.86 sq mi (10.00 km2) |

| • Water | 0.08 sq mi (0.21 km2) |

| • Urban | 4.83 sq mi (12.5 km2) |

| Elevation | 843 ft (257 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• City | 4,860 |

| • Density | 1,200/sq mi (480/km2) |

| • Demonym | Omakian |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 98841 |

| Area code | 509 |

| FIPS code | 53-51340 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1524048[2] |

| Website | www |

Omak (/oʊˈmæk/ o-MAK[3]) is a city located in the foothills of the Okanogan Highlands in north-central Washington, United States. With a population of 4,860 residents as of 2020, distributed over a land area of 3.43 square miles (8.9 km2), Omak is the largest municipality of Okanogan County and the largest municipality in Central Washington north of Wenatchee. The Greater Omak Area of around 8,229 inhabitants as of the 2010 census is the largest urban cluster in the Okanogan Country region, encompassing most of its twin city of Okanogan. The population has increased significantly since the 1910 census, reporting 520 residents just prior to incorporation in 1911.

The land that is now Omak had been inhabited by various Native American tribes before the arrival of non-indigenous settlers in the early 19th century. The city began to develop after the completion of the Okanogan Irrigation Project affecting the Grand Coulee Dam and other nearby electric facilities. The housing and municipal infrastructure, along with regional infrastructure connecting the new town to other municipalities, were built simultaneously in 1908 supported by the local agricultural industry. The name Omak comes from the Okanagan placename [umák],[4] or the Salishan term Omache—which is said to mean "good medicine" or "plenty", referring to its favorable climate, with an annual high of around 88 °F (31 °C). Omak acts as the gateway to the Okanogan–Wenatchee National Forest and consists of a central business district and residential neighborhoods.

Omak is a code city governed by a seven-member council and located in the state's 4th congressional district. Omak's economy is dominated by the primary sector industries of agriculture and forestry, although economic diversification has occurred with sawmills and recreational tourism. Nearby recreational destinations include walking trails, state parks and national forests, such as Conconully State Park, Bridgeport State Park and Osoyoos Lake State Park. The city is home to a weekly newspaper, the Omak–Okanogan County Chronicle, and a Wenatchee Valley College campus. Standards for education in Omak are higher than the state's average, though drugs and alcohol remain a problem among students. U.S. Route 97 passes through the town, while Washington State Route 155, as well as Washington State Route 215, connects the city to Okanogan and Nespelem, respectively. By road, Omak is located approximately 235 miles (378 km) from Seattle, Washington, 140 miles (230 km) from Spokane, Washington and 125 miles (201 km) from Kelowna, British Columbia.

History

[edit]Origin

[edit]The Okanogan Valley was the traditional homeland of the Syilx (also called Okanogan) Native Americans, whose territory extended north into what is now British Columbia. The Syilx acquired horses in the mid-18th century, which helped them expand northward. They first met non-native traders and missionaries in the early 19th century. The Syilx participated in trade fairs held at Kettle Falls and at the mouth of the Fraser River. Trading networks strengthened after the acquisition of horses in the mid-18th century.[5]

In 1811, Fort Okanogan was built by the Pacific Fur Company at the confluence of the Okanogan and Columbia Rivers. The fort's ownership passed to the North West Company, then the Hudson's Bay Company. Fort Colvile, near Kettle Falls, was another important fur trading outpost. The Okanogan River was used by fur brigades traveling between Fort Okanogan and Kamloops. In the late 1850s this route became known as the Okanagan Trail and was widely used as an inland route to the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush.

In the 1850s, European-Americans settled in the area that is now Omak and built houses and inaugurated mining, logging and agricultural activities. As more white settlers arrived, a dispute about land ownership arose between them and the Native Americans.[6]

In response, a treaty stating that an Indian reservation would be formed on some of the disputed land while the European-Americans would own the remaining land was signed. The Indian land was later reduced to about 5,000,000 acres (2,000,000 ha). Colville Indian Reservation was developed around 1872 during the Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. In 1887, the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, a federally recognized tribe, was formed by executive order from 12 individual bands as per the General Allotment Act of 1887. The federal government decided to move Colville Indian Reservation's location west of Columbia River, reducing its area to 2,800,000 acres (1,100,000 ha). It would continue to be reduced for the next 60 years.[6]

Nearby Alma was platted as an unincorporated community around 1886. Alma was renamed Pogue in honor of orchardist J.I. Pogue, and was later renamed Okanogan—the present name. J.I. Pogue was upset that his name was replaced, and requested that surveyor, civil engineer and settler Ben Ross establish another town 4 miles (6.4 km) to the north.[7] Born in Bureau County, Illinois, Ross worked for the Great Northern Railroad shortly before moving to Okanogan County.[8] He decided to found a new community at Pogue's proposed location during 1907.[7] It was named Omak, supposedly for the Salishan word Omache—said to mean "good medicine" or "plenty"—and referring to the town's favorable climate;[6] although according to William Bright the name comes from the Okanagan placename [umák].[4] Ross sold various items on the present townsite, trying to have his town recognized,[7] and built a cabin in 1907 to provide shelter for his daughter, son and grandchildren—becoming one of the first white men to settle the area.[9]

Growth

[edit]

The town began to develop after the completion of the Okanogan Irrigation Project, which was designed to facilitate farming. At this time, many farmers came to Omak looking for homes.[10][11] Fruits including apples, berries, peaches, plums and watermelons were cultivated after 1910.[12] Omak served as a census-designated place (CDP) in 1910,[13] and incorporated as a city on February 11, 1911.[14] Omak and Okanogan have shared a rivalry in high school sports. During the Great Depression of 1933, several residents of Omak were forced to work in nearby communities. As a result, the United States Bureau of Reclamation promoted work which was available as part of an improvement project at Grand Coulee Dam in nearby Coulee Dam, which employed approximately 5,000 people between 1933 and 1951 when the megaproject ended.[6] By 1950, the city was home to various buildings and structures including the St. Mary Mission church, which satisfied residential needs.[6][15][16]

In the 1910s, Omak was chosen as the location for a sawmill to expand economic growth. Omak Fruit Growers controlled the mill and a nearby orchard processing factory. The Biles-Coleman Lumber Company bought out the organization and built a sawmill outside municipal boundaries on the nearby Omak Mountain in 1924. A secondary sawmill was constructed in the Omak area. The company and their mills were purchased in 1975 by Crown Zellerbach and thus an associated organization—Cavenham Forest Industries—acquired the mills. The company ultimately went bankrupt, and in response, employees purchased the mill for 45 million dollars and renamed it Omak Wood Products in an attempt to save their jobs.[6] Omak Woods Products' payroll decreased to 480 in the early 1990s and later went bankrupt themselves, along with Quality Veneer, who later owned the property for 19 million dollars until 2000.[6] The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation later purchased the mill for 6.6 million dollars, having closed in 2009 because of low demand, ending over 130 jobs.[17] As of 2013, there are proposals to reopen the mills during the summer season.[18] The mill has since partially burned down in the Cold Springs Fire on September 8, 2020.

Geography

[edit]Topography

[edit]

The Canada–United States border—with an official crossing into Osoyoos, British Columbia from Oroville—lies approximately 45 miles (72 km) to the north.[19] The Idaho border lies about 160 miles (260 km) southeast.[20] The state's largest city, Seattle, lies 237 miles (381 km) southwest of Omak.[21] The Okanogan River, coming out of the town of Riverside, defines the city's northern border, while the southern border is defined by the city of Okanogan; the terrain here is mountainous and forested.[22] The nearest primary statistical area is the Wenatchee – East Wenatchee metropolitan area.[23] A CDP located northeast of the city was named North Omak because of its proximity to Omak. It is part of two census county divisions: Omak (western half) and Colville Reservation (eastern half).[24][25]

Omak, situated in the foothills of the Okanogan Highlands in central Okanogan County,[26] is part of the Okanogan Country region, extending into British Columbia.[27][28] It also lies within the Inland Northwest, centered on Spokane, and the Columbia Plateau ecoregion near the Okanogan Drift Hills.[29] The Okanogan River, a 115-mile (185 km) tributary of the Columbia River, flows through the central portion of the city,[22] and receives Omak Creek from the east just outside municipal boundaries.[22] Known for its balancing Omak Rock,[30] the 3,244-acre (1,313 ha) Omak Lake—950 feet (290 m) above sea level—is the largest saline endorheic lake in Washington.[31][32] The 80-acre (32 ha) Crawfish Lake is located about 15 miles (24 km) northeast of Omak at the border of the Colville Indian Reservation and Okanogan–Wenatchee National Forest.[33] The 1,499,023-acre (6,066.33 km2) forest comprises varied terrain and several mountain peaks.[34]

Elevations around the area range from 780 feet (240 m) above sea level at the mouth of the Okanogan River to 6,774 feet (2,065 m) above sea level at the Moses Mountain.[35] The average elevation is 843 feet (257 m) above sea level according to the United States Geological Survey (USGS). The Moses Mountain, with a summit, sits east of the city,[36] while Little Moses Mountain, located 5,963 feet (1,818 m) above sea level, and Omak Mountain, located 5,749 feet (1,752 m) above sea level, are adjacent to the Moses Mountain.[35] West of the city are the North Cascades, anchored by the Cascade Range.[22] Mountain peaks on the western portion of the Omak area range between 6,000 feet (1,800 m) and 8,000 feet (2,400 m).[37] The Coleman Butte mountain summit—1,450 feet (440 m) above sea level—is located directly adjacent to municipal boundaries.[38][39]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city encompasses a total area of 3.5 square miles (9.06 km2), including 0.07 square miles (0.18 km2) of water, accounting for two percent of the overall area.[40] The area expanded in April 2010, when 0.56 square miles (1.5 km2) of land formerly within the city of Okanogan was accumulated.[41] Omak is the fourth largest settlement in Okanogan County by area after Nespelem Community (23 sq mi; 60 km2), North Omak (11.2 sq mi; 29 km2) and Disautel (3.80 sq mi; 9.8 km2).[40] Omak covers 0.07 percent of the county's total area. Its 4.83-square-mile (12.5 km2) urban cluster, the Greater Omak Area, includes the city of Okanogan and the CDP of North Omak.[42][43] The surrounding metropolitan region comprises a total area of 1,037 square miles (2,690 km2), although it has not officially been designated as a statistical area.[44]

Climate

[edit]

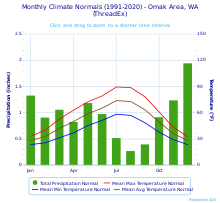

The city experiences a semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSk), with little precipitation, hot summers and cold winters. Average temperatures in Omak range from a 23.3 °F (−4.8 °C) minimum in January to a 89.4 °F (31.9 °C) maximum in July. The lowest temperature recorded was −26 °F (−32 °C) on February 1, 1950, and the highest was 117 °F (47 °C) on June 27, 2021. The annual daily mean temperature is 49.9 °F (9.9 °C). Average monthly precipitation ranges from 0.49 inches (12 mm) in August to 1.66 inches (42 mm) in December.[45][46] Despite Omak's geographical location further north and very close to the Canadian border, the city of Wenatchee, further to the south has almost the same average annual temperature.[47] as well as several other southern communities.[48][49]

Omak experiences four distinct seasons.[37] Summers are hot and relatively dry, with a daily average of 72.2 °F (22.3 °C) in July, while winter is the wettest season of the year, with 22.3 inches (570 mm) of snowfall between November and February. Spring and autumn are mild seasons with little precipitation.[45][46] The city is located in plant hardiness zone 6a, according to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).[50] In July 2012, a severe thunderstorm occurred in Omak, producing heavy rainfall, gusty winds and hail, and forced the temporary closure of U.S. Route 97 and requiring repairs to public streets.[51] Omak was affected by the 1872 North Cascades earthquake—the state's largest historical earthquake—which occurred on December 14, 1872.[52][53] The epicenter was at Omak Lake.[54] The earthquake had a magnitude of between 6.5 and 7.0 and was followed by an aftershock.[55][56] Another earthquake with minor shaking affected the city in November 2011.[57][58]

| Climate data for Omak, Washington, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1909–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 62 (17) |

63 (17) |

79 (26) |

96 (36) |

104 (40) |

117 (47) |

114 (46) |

109 (43) |

102 (39) |

90 (32) |

77 (25) |

74 (23) |

117 (47) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 45.6 (7.6) |

51.9 (11.1) |

66.0 (18.9) |

77.3 (25.2) |

88.0 (31.1) |

95.2 (35.1) |

101.7 (38.7) |

101.4 (38.6) |

92.5 (33.6) |

76.4 (24.7) |

58.3 (14.6) |

46.2 (7.9) |

103.3 (39.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 32.8 (0.4) |

39.8 (4.3) |

52.5 (11.4) |

62.8 (17.1) |

72.4 (22.4) |

79.1 (26.2) |

89.4 (31.9) |

88.8 (31.6) |

78.2 (25.7) |

60.7 (15.9) |

43.0 (6.1) |

32.5 (0.3) |

61.0 (16.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 28.0 (−2.2) |

32.5 (0.3) |

41.8 (5.4) |

49.8 (9.9) |

58.8 (14.9) |

65.1 (18.4) |

73.7 (23.2) |

72.8 (22.7) |

63.3 (17.4) |

49.1 (9.5) |

35.9 (2.2) |

27.9 (−2.3) |

49.9 (9.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 23.3 (−4.8) |

25.2 (−3.8) |

31.1 (−0.5) |

36.8 (2.7) |

45.1 (7.3) |

51.1 (10.6) |

58.1 (14.5) |

56.8 (13.8) |

48.4 (9.1) |

37.5 (3.1) |

28.9 (−1.7) |

23.3 (−4.8) |

38.8 (3.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 4.2 (−15.4) |

10.2 (−12.1) |

18.8 (−7.3) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

30.5 (−0.8) |

38.8 (3.8) |

45.1 (7.3) |

44.9 (7.2) |

33.5 (0.8) |

22.3 (−5.4) |

12.7 (−10.7) |

6.1 (−14.4) |

−0.6 (−18.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −22 (−30) |

−26 (−32) |

−7 (−22) |

15 (−9) |

19 (−7) |

30 (−1) |

35 (2) |

31 (−1) |

20 (−7) |

5 (−15) |

−6 (−21) |

−21 (−29) |

−26 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.33 (34) |

0.91 (23) |

1.06 (27) |

0.83 (21) |

1.19 (30) |

0.98 (25) |

0.52 (13) |

0.27 (6.9) |

0.40 (10) |

0.92 (23) |

1.24 (31) |

1.95 (50) |

11.60 (295) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 8.0 (20) |

4.7 (12) |

0.8 (2.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

3.0 (7.6) |

8.5 (22) |

25.0 (64) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.0 | 8.0 | 7.6 | 5.8 | 7.6 | 6.7 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 3.8 | 6.0 | 9.1 | 11.5 | 81.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 4.1 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 3.9 | 12.2 |

| Source 1: NOAA[59] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service (average snowfall/snow days 1909-1997) [60] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

[edit]

Omak is a planned city. Throughout the 20th century, Ross designed what would become the city of Omak.[8][61] Within a year of its establishment, the town had a central business district with a public bank and hotel supported by the local agricultural industry.[6][62] The town was provided with a post office, previously known as Epley. Ross founded Omak School District in 1906; soon after this its first school, Omak Schoolhouse, was built. In 1910, a meat market, hardware shop, law office, stationery and confectionery store were constructed in Downtown Omak.[63] A steel bridge built the following year collapsed into the Okanogan River upon initial use. It was quickly rebuilt with no further problems.[7][64]

The city consists of a central business district and residential areas.[6][65] Downtown Omak, the central business district, is the economic center for Omak and Okanogan County. There are several functional churches in the city.[66] The post office in Omak—managed by United States Postal Service (USPS)—is the city's only listing of the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP).[67] The Breadline Cafe is a notable restaurant and music venue in Downtown Omak.[68][69] The City of Omak maintains the Omak Memorial Cemetery, comprising around 3,747 graves in a region located adjacent to Washington State Route 215, having been formerly known as Okanoma Cemetery.[70] The 118-acre (48 ha) North Omak Business Park, the city's business park, is bordered by U.S. Route 97 from the east.[71][72] The city's residential neighborhoods are encompassed by East Omak and South Omak.[6][73]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 520 | — | |

| 1920 | 525 | 1.0% | |

| 1930 | 2,547 | 385.1% | |

| 1940 | 2,918 | 14.6% | |

| 1950 | 3,791 | 29.9% | |

| 1960 | 4,068 | 7.3% | |

| 1970 | 4,164 | 2.4% | |

| 1980 | 4,007 | −3.8% | |

| 1990 | 4,117 | 2.7% | |

| 2000 | 4,721 | 14.7% | |

| 2010 | 4,845 | 2.6% | |

| 2020 | 4,860 | 0.3% | |

| Sources: Greater Omak Comprehensive Plan[13] [74] U.S. Decennial Census[75] 2020 Census[76] | |||

The 1910 United States Census, before the city's incorporation, recorded 520 residents. The following 1920 census—the first to define Omak as a distinct subdivision—counted 2,500 residents, making it the most populous municipality of Okanogan County, having surpassed Okanogan (1,519 residents).[6][13] Subsequent census counts documented an increase to 4,000 residents before a shrink in population at the 1980 census, when fruit prices rose, land was lost, and major employers were shut down.[6] After this decline, the population steadily increased, approaching approximately 5,000 residents by the 2000 census. Between 1990 and 2000, the city's population experienced a boom of 14.7 percent,[13] while between 2000 and 2010, the population increased by around 2.6 percent.[41][77] The United States Census Bureau estimated that there were 4,792 residents in 2013, representing a 0.6 percent increase over the 2010 census,[78] while an estimate from Office of Federal Financial Management in 2013 documented a population decrease of 0.3 percent to 4,830 people.[79] A 2011 study from the United States Census Bureau showed that there were 4,881 residents, a 0.7 percent increase over the 2010 census.

According to the 2010 census, Omak had 4,845 residents living in 2,037 households, with 1,412.5 inhabitants per square mile (545.4/km2). These residents created an average age of 38—one year higher than that of the entire state.[77] About 15 percent of residents were single and 13 percent were lone-parent households. With 2,168 housing units at an average density of 632.1 inhabitants per square mile (244.1/km2), the city's populace consisted of 2,540 females and 2,305 males, giving it a gender balance close to national averages with 14.8 percent male and 11.9 percent female.[80] The racial makeup was dominated by white people, with 71 percent of the population. Between the 2000 and 2010 censuses, Omak had an increase of 10 families to 1,230 and a decrease of 21 lone-parent families. Omak had an urbanized population of 8,229 people, with 1,737 inhabitants per square mile (670.7/km2) and around 20 percent of the county's residents.[43][81] The last complete census in 2000 found that the average household consisted of around two residents and the average family consisted of approximately three people.[74]

Approximately 89.5 percent of residents over the age of five spoke English at home, according to the 2007–2011 American Community Survey. It was then estimated that 889 people, comprising 18.5 percent of local inhabitants have German ancestry—the largest ethnicity in Omak—and 15.3 percent have Irish ancestry. The Omak area has a relatively high percentage of people of American Indian and Mexican ancestries; there were over 800 American Indians and over 535 Mexican immigrants, with a combined percentage of 28 percent of residents. Conversely, the city has a small Asian population, making up less than one percent of Omakians. The 2010 census showed that approximately 35 percent of residents lived alone, most of whom were female. Those over the age of 65 comprised about 16 percent of the population.[74] There have been several efforts to provide service to the homeless people of Omak,[82] although official population figures have not been released.

Economy

[edit]

Omak is the commercial center for the rural communities of Okanogan County and other nearby settlements.[6] It is the regional center for services and trade in the county. As of 2007[update], the city's economy is experiencing significant growth, according to the County of Okanogan.[83] It is an agricultural community with a reliant forestry industry. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, almost 90 percent of Omak's manufacturing jobs were in the city's two sawmills. Infrastructure services and retail trades were also major industries. About 425 private firms employed a total of 3,332 workers in local industries including manufacturing, retail and infrastructure, at this time.[6] Located within Greater Omak, the adjacent city of Okanogan serves as the administrative center for Okanogan County, the region's largest employer.[84]

As of 2010[update], there are 1,859 civilians over the age of 16 employed in the city of Omak. Despite its recognition as an agricultural community, there were only 26 inhabitants employed in the agriculture and forestry industries, but the surrounding area has more agricultural jobs. Office and sale services were the largest occupation in Omak, comprising approximately 30 percent of the city's total employees, followed by business occupations, with 26.5 percent. Majority of residents work in public services.[85] Approximately seven percent of people in Omak are unemployed, while 25 percent live below the poverty line, including 34 percent of those under 18 and 10 percent of those aged 65 or over. The cost of living rate is 85.5 per unit, less than state and national averages. During the 2007–2011 American Community Survey, the city had a per capita income of $17,785 and an average income of $31,649 per household.[85] Omak's 98841 zip code maintained 265 businesses in 2011, with an average payroll of $78,884.[86]

The city has a Walmart store, which was built in 1993 as the state's first such store,[87] serving over 60,000 residents.[88] The process of opening the retail facility took various discussions and approvals. Proposals in Omak began around 1992, in which 93,188 square feet (8,657.4 m2) of land were expropriated from the Omak Planning Commission.[89][90] Local retailers feared that the chain would devastate their businesses, although other people felt that it would increase business at other shopping regions in the city.[88] Shortly after its opening, numerous shoppers came to the Omak area looking for items. Walmart hired approximately 200 employees, boosting the city's economy significantly and becoming among Okanogan County's largest retailer for a short period.[87] The store was later allowed to remain open for 24 hours per day.[91]

Omak's economy is also driven by a mixture of tourism. Nearby recreational destinations, with their mild climate, increase the local economy significantly. The local Harbor Freight, Big 5 Sporting Goods, North 40 and Walmart retail stores maintain license vendors for recreational activities.[92] There is a 1,541,470-square-foot (143,207 m2) shopping mall, the Omache Shopping Center, located in North Omak Business Park along U.S. Route 97,[72][93] which attracts residents from nearby rural communities.[94] Established in 1987,[95] the mall is home to 12 stores and services.[93] Omak is the headquarters of two infrastructure organizations: Okanogan County Transportation & Nutrition[96] and Cascade and Columbia River Railroad.

Culture

[edit]Nicknames

[edit]The municipality has been named a "tree city" for ten consecutive years since April 2007.[97] The Washington Department of Natural Resources announced on April 11, 2013, that Omak had again been named a "tree city" because of their continuous efforts to "keep urban forests healthy and vibrant" for 15 years.[98] The City of Omak brands itself as the "Heart of the Okanogan"—referring to its significant economic importance in the Okanogan. The Okanogan County Tourism Council uses the same branding to define the Greater Omak region.[26][99] It is officially recognized as the City of Omak;[26] Omak residents are known as Omakians.[100]

Tourism

[edit]

The Omak Stampede, which operates the Suicide Race, has been hosted at a local rodeo facility, the Stampede Arena—renovated in 2009[101]—since 1933.[102][103] The Omak Stampede occurs annually on the second weekend of August. During the event, the city has an estimated population of approximately 30,000 people.[104][105] As part of the Suicide Race, horses and riders run down Suicide Hill—a 62-degree slope that runs for 225 feet (69 m) to the Okanogan River.[106] Horses must pass a veterinarian examination to ensure they are physically healthy, and a swim test to ensure they can cross the river, to demonstrate their ability to run the race and navigate the river.[107] Several animal rights groups, including Progressive Animal Welfare Society (PAWS), In Defense of Animals and Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), have expressed concerns about the horses' welfare and have opposed the specific event.[108][109]

Other significant events include the Omak Film Festival, inclusive of a variety of films at the Wenatchee Valley College and Omak Theater,[110][111] the Okanogan County Fair, an annual carnival at the County Fairgrounds[112] and the Omak Western and Native Art Show, a Native American carnival.[113] In an attempt to increase tourism, the City of Omak operates a Main Street Historical Tour in the central business district.[114] A local recreational complex comprises a Native American wooden sculpture area.[115] Two functional movie theaters, the single screen Omak Theater, built in 1928, and the Mirage Theater with three screens, built in 2004, service the city.[116][117] A drive-in theater, with a capacity of 250 automobiles, was proposed in 1948, but never built.[118]

The Omak Visitor Information Center—deemed the "best little information center in the west"—has historical images and a gift shop offering pamphlets regarding Okanogan County and surrounding regions.[68] The Okanogan County Historical Museum comprises a historic fire hall, research center, genealogical area and a display of historical photographs or the area. The Omak Performing Arts Center—a 500-seat venue which hosts presentations, ceremonies, and performances—was built by Omak School District in 1989.[6][119] There is a 58,000-square-foot (5,400 m2) casino operated by the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation since 2008, incorporating over 400 gaming machines, a convention center, and an arcade.[120] Nearby Okanogan Bingo Casino, along U.S. Route 97, also primarily serves Omak, consisting of approximately 360 gaming machines.[121]

Recreation

[edit]The area's mild climate and its close proximity to lakes, rivers, and mountains make Omak an outdoor recreational destination. The city maintains eight general recreational complexes, of which the 76.6-acre (31.0 ha) Eastside Park, with an enclosed skate park, municipal pool, seven baseball diamonds, four soccer fields and tennis courts, and two basketball courts, is the largest.[122] Civic League Park is the municipality's oldest park, while Dalton Klessig Park is the newest.[123] The Omak City Park Board has been formed to protect these public spaces.[124] Omak has several beaches at the north–south shores of Omak Lake on the Colville Indian Reservation, comprising over 100 acres (40 ha) of sandy land.[125][126] Fishing and boating are available at Omak Lake,[127][128] and at the Fry Lake and Duck Lake—near the city's local airport[22][129]—and Conconully Lake, Crawfish Lake and the Okanogan River, all of which are home to several species.[130][131] The Valley Lanes bowling alley serves the city and has hosted intrastate competitions,[132] while the Okanogan Valley Golf Club—a country club with 334-and-284-yard (305 and 260 m) golf courses—is located in Omak.[133]

The Okanogan–Wenatchee National Forest, the largest forest on the West Coast, provides residents with trails for walking, hiking and cycling close to home and encompasses several skiing regions.[134][135] It received approximately 397,000 visitors in 2005,[136] most of whom came from over 50 miles (80 km) away.[137] Numerous general recreational opportunities, such as hunting and rock scenery, are available nearby.[134] There are various hiking trails in nearby hilly areas, including Omak Mountain and its look-out tower,[138] and Moses Mountain.[139] The Granite Mountain Trail is located between the forests about 33 miles (53 km) away from the city.[140][141] There is skiing available about 25 miles (40 km) west of town at the Loup Loup Ski Bowl.[142][143] Nearby state parks include Conconully State Park (17 mi or 27 km northwest),[144] Bridgeport State Park (36 mi or 58 km south),[145] Osoyoos Lake State Park (41 mi or 66 km north),[146] and Alta Lake State Park (47 mi or 76 km southwest),[147] Birdwatchers can see quail, anatidae, turkey buzzard, wild turkey and bald eagles in the Omak area.[99]

Camping is available at local recreational vehicle parks (RV parks), including Carl Precht Memorial RV Park,[148] Sunset Lakes RV Park (adjacent to Duck Lake),[129] and Margie's R.V. Park.[149] There are over a half-dozen campgrounds in proximity to Omak.[150] The Omak–Okanogan region has been well known for its rock climbing structures since the early 1970s.[151] Nearby communities in Okanogan County offer horseback riding and hunting.[65] Fishing and boating is achievable within short distance,[131] at the nearby Omak Lake.[127][128] The Omak Pioneers represent Omak High School as their baseball,[152] basketball,[153] football,[154] soccer,[155] volleyball,[156] and wrestling teams.[157] There are separate teams based on age and gender.[158] There are all-terrain vehicle (ATV) courses located nearby, specifically in the Loup Loup Ski Bowl.[159]

Media

[edit]

In 1910, C.P. Scates established the Omak Chronicle.[160] Three years later, it was renamed The Omak-Okanogan County Chronicle and expanded its coverage to the whole county as its primary newspaper.[161] In February 1998, an online version was established,[162] which had approximately 170,000 viewers in April 2013.[163] Since then, the newspaper has been expanded to serve nearby Ferry County.[162][164] The Okanogan Valley Gazette–Tribune, based in Oroville, and The Wenatchee World, based in Wenatchee, serve Omak as alternative publications.[165][166] Okanogan Living, a monthly lifestyle magazine based in Tonasket, also serves the region.[167]

John P. and Becki Andrist own three licensed radio stations in the city.[168] Branded as "Radio Okanogan", KOMW broadcasts an oldies format and serves the entire valley floor,[169] while country music station KNCW (branded as "Okanogan Country Radio" features programming from Citadel Media and Dial Global.[170] KZBE also broadcasts programming from Dial Global in the adult contemporary format,[171] while KQWS operates from Washington State University as Northwest Public Radio.[172]

Omak is well-served by television and radio, with all major U.S. networks and at least five other English-language stations available. Omak cable viewers can also receive CHAN-DT (Global Television Network) from Vancouver, British Columbia.[173] The nearest major television market area is based in the Seattle metropolitan area.[174] The Omak–Okanogan market area includes several broadcast television stations that can be received in the city. K17EV-D, channel 17—a broadcast translator of KSPS-TV—is branded as Public Broadcasting Service (PBS),[175] while K07DG, channel 7, rebroadcasts KREM, a CBS affiliate, in the municipality.[176] An American Broadcasting Company (ABC) affiliate, KXLY-TV is translated as K09DG in Omak.[177] K11DM, channel 11, is a translator of National Broadcasting Company (NBC)'s KHQ-TV,[178] Community television stations, K19AU-D and the Fox Broadcasting Company translator at K31AH-D, are owned by Mountain Licenses and operate from Omak,[179][180] in addition to a Three Angels Broadcasting Network-owned station, K26GV-D.[181] The Riverside market area is nearby and contains three licensed television stations which can be received, including K08CY,[182] K10DM,[183] and K12CV.[184]

Government and politics

[edit]

The City of Omak's mayor–council government comprises a mayor—who also represents north-central Washington's separate economic development district[185]—and a seven-member council.[186] These positions, stipulated by the Omak City Code,[187] are subject to at-large elections every two years, rather than by geographic subdivisions.[188][189] Like most portions of the United States, government and laws are run by a series of ballot initiatives whereby citizens can pass or reject laws, referendums whereby citizens can approve or reject legislation already passed, and propositions where specific government agencies can propose new laws or tax increases directly to the people. Federally, Omak is part of Washington's 4th congressional district,[190] represented by Republican Dan Newhouse, who was sworn in on January 3, 2015. The current mayor, Cindy Gagne, was first elected in 2000 as a councilwomen, and was appointed in May 2009.[191]

The State of Washington operates a public government administration office in Omak for access to social and health assistance.[192] Omak is considered to be a code city,[193] based on proposals to provide the local government with more authority from its previous second-class city status.[194] With a functional court for traffic, parking and civil infractions, the city maintains the sewer, water, local road, sidewalk, street lighting, animal control, building inspection, park, and recreation services. It also funds a volunteer fire department which services Omak and nearby rural communities.

Omak is also governed by an eight-member planning commission—part of the Omak City Council—which also operates the Greater Omak Comprehensive Plan, adopted in April 2004 and consisting of improvements considered for the city and surrounding communities.[37][195] The five-member Omak Library Board and Tree Board are also divisions of the Omak City Council, with public meetings taking place at the Omak Public Library.[196] With four-year terms for participants, the local Civil Service Commission services Omak.[197] Shortly after being incorporated in 1911, Omak unsuccessfully contested Okanogan to become the administrative center of Okanogan County, after Conconully lost its status.[198] During the temperance movement before national prohibition, Omak residents favored the banishment of alcohol in Washington, which was opposed by those of Okanogan.[7] The United States Army (USA) operates two military recruiting centers in Omak,[199] although a historical military band, the Omak Military Band, also operated around 1910.[200]

The five-officer Omak Police Department detachment, which covered the municipality and nearby rural communities, reported over 180 criminal code offenses in 2010. The city's crime rate of 154 offenses per 100,000 people is 28 percent higher than the 2010 state average and one percent higher than the 2010 federal average.[201] According to Uniform Crime Report statistics compiled by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 2011, there were 19 violent crimes and 166 property crimes. The violent crimes consisted of one forcible rape, three robberies and 15 aggravated assaults, while 32 burglaries, 104 larceny-thefts, eight motor vehicle thefts and one arson defined the property crimes. The FBI classifies Omak as having 4,921 people located within the Omak Police Department area.[202] The city's highest crime rate was recorded in 2004, with 413 incidents per 100,000 people. Until 2013, when a murder and motor-vehicle theft occurred in the city,[203] there had not been a homicide for over ten consecutive years.[204] The crime in Omak has decreased throughout the past decade.[205] Before marijuana was legalized in Washington, marijuana users were arrested, per state law.[206] Growers, drug lords and international smugglers residing in the Omak area are still arrested.[207]

Education

[edit]

The 2010 census estimated that 1,057 people in Omak have attended college, while 504 residents received an academic degree; more than five percent higher than the state average. Approximately 91.5 percent graduated from high school or a more advanced institution; two percent higher than the state average.[74][77] Omak's schools are administered by the county's largest educational district, Omak School District, which operate two mainstream high schools, one mainstream middle school, two mainstream elementary schools and three virtual schools.[208] Omak High School, built in 1919,[209] had a 2010–11 enrollment of 435 students,[210] while the Omak Alternative High School had an enrollment of 48 students. Omak Middle School had an enrolment of 339 children.[211] The city's primary schools are East Omak Elementary and North Omak Elementary which had a combined 2010–11 enrollment of 748 children.[212][213]

In February 2010, Omak became the third settlement in Washington to have a virtual school.[214] During the 2010–11 year, Washington Virtual Academy Omak Elementary, Washington Virtual Academy Omak Middle School, and Washington Virtual Academy Omak High School had a combined enrollment of 969 pupils.[215][216][217] The private Omak Adventist Christian School, which operates outside of Omak School District, had 16 pupils in 2011. It is affiliated with the nearby General Conference of the Seventh-day Adventist Church.[218] The Veritas Classical Christian School has also operated in the Omak region.[219]

The Omak Public Library, managed by NCW Libraries (formerly North Central Regional Library),[220] was established in 1956 under provisions of state law passed by the City of Omak.[221] The library is open daily, except on Sundays in the summer season.[196] The community college, Wenatchee Valley College,[222] maintains a campus in Omak,[223] which had an enrollment increase of 19 percent between the 2009–10 and 2010–11 educational seasons.[224] Located approximately 95 miles (153 km) from the main campus in Wenatchee,[225] it was established in the 1970s,[223] and offers adult education classes and two-year associate degrees.[226] Based in Toppenish about 215 miles (346 km) away,[227] Heritage University operates an Omak campus consolidated with Wenatchee Valley College's, providing degrees in several academic subjects.[228]

Infrastructure

[edit]

The 2010 census estimated that 89.3 percent of residents in Omak commuted to work by automobile; more than the state average of 72.4 percent. Four percent of residents carpooled; fewer than Washington's average. 3.8 percent walked; close to the state average. The median time to travel to work was 11.5 minutes, less than the state average of 25.5 minutes.[229] In the late 1960s, U.S. Route 97 was rerouted to the east and Downtown Omak was bypassed. Large signs located just off U.S. Route 97 promote the city's central business district.[68]

Washington State Route 215 runs north–south through Omak, connecting the city to Okanogan four miles (6.4 km) to the south. U.S. Route 97 and State Route 20 also run north–south through Omak, connecting the municipality to Okanogan 5 miles (8.0 km) south along this route and Brewster 32 miles (51 km) south, Nespelem 35 miles (56 km) southeast is connected to the community by the east–west State Route 155, before it becomes a spur route and continues west along Omak Avenue to terminate into State Route 215. The residential areas are separated from the industrial sector and the highway by backroads near the major highways. Omak's central business district is connected by several spur routes along municipal roads, such as Riverside Drive, Main Street and Okoma Drive.[230]

Omak has rail, air, and bus services for regional and state transportation. Rail lines from Cascade and Columbia River Railroad enter Omak from Oroville in the north and Wenatchee in the south. The line interchanges with BNSF Railway in the Wenatchee area.[231] The City of Omak operates the general Omak Airport. The paved runway is the third largest in central Washington.[232] The airport provides three daily charter flights, except on Saturdays and Sundays.[37] Wings for Christ Airport and Mid-Valley Hospital EMS Heliport are private aviation ports.[233][234] The closest commercial airports are located in Penticton[235] and East Wenatchee.[236] Okanogan County Transportation & Nutrition provides bus services in the city,[237][238] and the federal Amtrak and Greyhound Lines maintain bus stops there.[239][240]

The 30-bed Mid-Valley Hospital provides medical services, including a 24-hour emergency medical service, ambulance service, nursing care, a birthing center, and a trauma center.[241] The facility employs 10 physicians and dentists, 20 registered nurses and two licensed practical nurses.[242] Established in July 2000, Okanogan Behavioral Healthcare serves the city as an alternative medical facility.[243] Numerous nursing homes, including Rosegarden Care Center, New LifeStyles and The Source for Seniors, operate in Omak.[244] The city's clinic was constructed in 1996 using $4,800,000 of local funds.[245] The City of Omak measures residents' drinking water use and provides storm drains, solid waste, and garbage services since 1984. Residents under 60 are charged a 10 percent utility tax on purchases.[246] Electricity is supplied by Okanogan County Public Utility District,[247] and natural gas by Amerigas. Other utility companies serving Omak include AT&T (telephone);[248] and Comcast (telephone, Internet, and cable television).[249]

Notable people

[edit]

Joe Feddersen was born to a German American father and an Okanagan–Sinixt mother in Omak in 1953. Feddersen later became an active member of the Colville Indian Reservation and primarily serves as a sculptor, painter and photographer, known for creating artworks with strong geometric patterns reflective of the landscape and his Native American heritage. He was first exposed to printmaking at Wenatchee Valley College under the direction of Robert Graves and worked as an art instructor at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, after he earned his Bachelor of Fine Arts from the University of Washington and his Masters of Fine Arts degree from the University of Wisconsin–Madison.[250][251] In 2009, Feddersen moved back to Omak, after leaving his teaching position at the Evergreen State College.[252]

Marv Hagedorn was born in Omak in 1956. He was raised in northern Idaho and served in the United States Navy (USN) from 1973 to 1994 while attending Pensacola Junior College and the University of Maryland.[253] He entered politics and was elected to the Idaho House of Representatives by Governor Butch Otter in January 2007. In 2012, he was laid off,[254] and was elected to represent the Idaho State Senate. Outside politics he is a member of the Disabled American Veterans and North American Fishing Association.[255] Hagedorn and his wife later decided to reside in Meridian, Idaho, along with their children.[256]

Don McCormack was born in Omak in 1955. He later entered baseball and made his major league debut as a catcher with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1980, after being chosen as fourth round draft pick at the 1974 Major League Baseball Draft. McCormack would end up participating in a total of five games in the major league between 1980 and 1981 and spent nine years playing in the minor leagues for the Detroit Tigers and Philadelphia Tigers farm teams.[257] McCormack later managed the Reading Phillies (Eastern League) and served as the bench coach of the Long Island Ducks (Atlantic League) for a short period, but was replaced.[258][259]

William Stephen Skylstad, delivered in Omak on a garage table around 1934 to a Norwegian father and a Minnesotan mother, was raised on a farm near Skylstad, Norway, where his family later moved. When he was 14 years old, Skylstad left home to attend seminary in the United States, and was trained for the priesthood at Pontifical College Josephinum in Worthington, Ohio. Twelve years later, he was ordained a priest of the Diocese of Spokane on May 21, 1960. Skylstad serves as a Roman Catholic Bishop and a Bishop Emeritus of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Spokane, having retired on June 30, 2010. He was appointed as the Apostolic Administrator of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Baker, in Oregon, on January 24, 2011, upon the appointment of Bishop Robert F. Vasa as Coadjutor Bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Santa Rosa in California.[260]

International relations

[edit]According to the Lieutenant Governor of Washington, Omak is a sister municipality with Summerland, British Columbia,[261] a district with a population of 11,280 people according to the 2011 Canadian census.[262] Located on Okanagan Lake in the adjacent Okanagan-Similkameen Regional District, Summerland was incorporated on December 21, 1906,[263] and is located 96 miles (154 km) north of Omak.[264] An agricultural community like Omak, Summerland comprises several trails for hiking, walking or cycling.[265]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Omak". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ Merriam (1997), p. 869

- ^ a b Bright, William (2004). Native American Placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 350. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4.

- ^ Pritzker, Barry (2000). A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford University Press. pp. 270–272. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Tobe, Lisa. "Omak, Okanogan County, Washington" (PDF). Sierra Institute for Community and Environment. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 17, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Steigmeyer, Rick (March 20, 2008). "Omak—Stampede town". The Wenatchee World. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ a b "Ross's third addition to Omak, Okanogan County, Washington, (1928)". Washington State University. Archived from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ "Ben Ross cabin, Omak, Washington". University of Washington. Archived from the original on April 7, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ Matsura, Frank. "Streets of Omak, Washington in 1910". Washington State University. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ Matsura, Frank. "Concrete Lined Canal of the Okanogan Irrigation Project, ca. 1912". Washington State University. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ^ Matsura, Frank. "Watermelon Picnic Near Omak, Washington, ca. 1910". Washington State University. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Greater Omak Comprehensive Plan" (PDF). City of Omak. July 1, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 10, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- ^ "Cities and Towns, State of Washington Dates of Incorporation, Disincorporation, and Changes of Classification". Municipal Research and Services Center. 1979. Archived from the original on November 26, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "Colville mission and school, St. Mary's Mission, Omak, Washington". Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture. Archived from the original on April 3, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Matsura, Frank. "Omak, 1910". Washington State University. Archived from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ "Omak lumber mill closing in December". The Seattle Times. November 6, 2009. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ Mehaffey, K.C. (March 30, 2013). "Omak plywood mill to reopen after four-year shutdown". The Wenatchee World. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ "Omak, Okanogan, Washington to US-97 N, Washington" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ "Omak, Okanogan, Washington to W Seltice Way, Idaho" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ "Omak, Okanogan, Washington to Seattle, King, Washington" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Omak, Okanogan, Washington" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ "Table 1: Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". United States Census Bureau. July 1, 2012. Archived from the original (CSV) on April 1, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ "Omak, CCD Reference Map" (PDF) (Map). United States Census Bureau. October 5, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 26, 2014. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- ^ United States Census Bureau (2002), p. 166

- ^ a b c "Welcome to the City of Omak, Washington, United States". City of Omak. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ "Inland Empire". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ Koellman, Peg (March 11, 1987). "Omak events 'senseless'". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ Sleeter, Benjamin (December 13, 2012). "Columbia Plateau Ecoregion Summary". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ^ Mehaffey, K.C. (March 10, 2012). "More national press, and some good ol' hometown recognition". The Wenatchee World. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ "Omak, Okanogan, Washington to Omak Lake, Okanogan, Washington" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "Omak Lake, Okanogan County, Washington". Washington State University. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "Crawfish Lake – Okanogan County". Washington Department of Ecology. 1997. Archived from the original on March 10, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "Table 6 – NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County". United States Forest Service. September 30, 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ a b "Published Soil Surveys for Washington". United States Department of Agriculture. 1923. p. 23. Archived from the original on February 28, 2013. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- ^ Cushman (1918), p. 14.

- ^ a b c d "Omak Municipal Airport, Omak, Washington" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- ^ "Coleman Butte, Okanogan, Washington" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "Coleman Butte Summit – Washington Mountain Peak Information". MountainZone.com. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ a b "National 2010 file containing a list of all municipalities and census-designated places (including Puerto Rico and the Island Areas) sorted by UACE code". United States Census Bureau. April 1, 2010. Archived from the original (TXT) on January 31, 2013. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ a b "National 2000 file containing a list of all municipalities and census-designated places (including Puerto Rico and the Island Areas) sorted by UACE code" (ZIP). United States Census Bureau. April 1, 2000. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ "Urban Cluster Reference Map" (PDF) (Map). United States Census Bureau. April 1, 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ a b "National 2010 urban area file containing a list of all urbanized areas and urban clusters (including Puerto Rico and the Island Areas) sorted by UACE code". United States Census Bureau. April 1, 2010. Archived from the original (TXT) on October 28, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. 2013. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ a b "Omak 2 NW, Washington (456123) – Period of Record Monthly Climate Summary". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ a b "Average Weather for Omak, Washington". The Weather Channel. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ "Compare Averages and Records – Wenatchee, Washington to Omak, Washington". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on July 3, 2014. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ^ "Compare Averages and Records – Yakima, Washington to Omak, Washington". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ "Compare Averages and Records – Kennewick, Washington to Omak, Washington". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ "Plant Hardiness Zone" (Map). United States Department of Agriculture. October 1, 2004. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ McNiel, Michelle (July 23, 2012). "Omak still cleaning up from last Friday's thunderstorm". The Wenatchee World. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ^ Walsh, Timothy; Gerstel, Wendy; Pringle, Patrick; Palmer, Stephen. "Earthquakes in Washington". Washington Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on April 3, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ^ "Washington – Earthquake History". United States Geological Survey. November 1, 2012. Archived from the original on March 27, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ^ Weichert, Dieter (April 1, 1994). "Omak rock and the 1872 Pacific Northwest earthquake". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. GeoWorldJournal. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ^ "The 1872 Magnitude 7.4 Washington State USA earthquake". Natural Resources Canada. March 17, 2011. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ^ Bakun, W.H.; Haugerud, R.A.; Hopper, M.G.; Ludwin, R.S. (2002). "The December 1872 Washington State Earthquake". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 92 (8). Pacific Northwest Seismic Network: 3239–3258. Bibcode:2002BuSSA..92.3239B. doi:10.1785/0120010274.

- ^ Mehaffey, K.C. (November 18, 2011). "Omak quake felt throughout NCW, state". The Wenatchee World. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ^ "Small earthquake hits B.C.'s Okanagan". CBC News. November 18, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on September 13, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data". National Weather Service. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Omak [verso], January 1, 1907". Washington State University. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ Matsura, Frank. "Bart Robinson's Hotel in Omak, Washington ca. 1910". Washington State University. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ Matsura, Frank. "Street Scene in Omak, Washington, 1910". Washington State University. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ Matsura, Frank. "Omak Bridge Collapses, ca. 1911". Washington State University. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Hornaday, Michelle. "Hotels in Omak, Washington". USA Today. McLean. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ "Churches in Omak, Washington". Yahoo! Local. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ a b c Larsen, Jeff (October 13, 2004). "Short Trips: Omak has a big reputation and heart". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "Great jazz, big-band sounds, can be heard locally, bar none". The Spokesman-Review. February 4, 1994. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ Wyman, Kim. "Omak Memorial Cemetery". Secretary of State of Washington. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ "Important Development Information". North Omak Business Park. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ a b "Aerial Photographs". North Omak Business Park. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ "Moving Truck Rental in Omak, Washington at Mac's Tire of Omak". U-Haul International Inc. Retrieved May 1, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Community Facts – Selected Social Characteristics in the United States – 2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates – Omak city, Washington". United States Census Bureau. April 1, 2010. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ "Census Bureau profile: Omak, Washington". United States Census Bureau. May 2023. Retrieved May 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Community Facts – Selected Social Characteristics in the United States – 2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates – Washington, state". United States Census Bureau. April 1, 2010. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 22, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ "April 1, 2013 Population of Cities, Towns and Counties – Used for Allocation of Selected State Revenues – State of Washington" (PDF). Office of Federal Financial Management. June 15, 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 20, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ "Community Facts – Selected Social Characteristics in the United States – 2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates – United States". United States Census Bureau. April 1, 2010. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "State & County QuickFacts – Okanogan County, Washington". United States Census Bureau. 2012. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ Crownover, Matt (June 4, 2008). "Commissioners updated on homelessness efforts". Omak–Okanogan County Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ "Okanogan County, Washington – Demographics". County of Okanogan. Archived from the original on June 25, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "North Central Workforce Development Council – Serving Region 8: Chelan, Douglas, Grant, Adams & Okanogan Counties" (PDF). North Central Workforce Development Council. May 1, 2009. Retrieved May 5, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Community Facts – Selected Economic Characteristics – 2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates – Omak city, Washington". United States Census Bureau. April 1, 2010. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "98841 – Omak, Washington – Number of Establishments". United States Census Bureau. 2011. Archived from the original on April 18, 2005. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ a b Wilma, David (July 1, 2007). "Wal-Mart opens its first store in Washington at Omak on May 1, 1993". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ a b Corr, O. Casey (May 2, 1993). "Enter the Giant – Largest Retailer in the Nation Steps into Small-Town Washington". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Nogaki, Sylvia (June 17, 1992). "Look Out, Here Comes Wal-Mart". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Nogaki, Sylvia (June 16, 1992). "Wal-Mart To Open Store In Kennewick". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "Omak Walmart Supercenter Store #1947". Walmart Stores, Inc. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "License Vendors – Authorized License Sales Locations – Okanogan County, Washington". Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ a b "Omache Shopping Center, Omak, Washington". Black Realty Management. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Monattey, K.C. (November 26, 2012). "Omak's commercial area sees Big changes". The Wenatchee World. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ "2012 Draft Comprehension Plan – Part 2 A – Land Use" (Doc). City of Omak. October 1, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "Home – Contact Information". Okanogan County Transportation & Nutrition. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ^ Thew, Chris (April 25, 2007). "Okanogan, Omak plant Arbor Day trees; gazebo named". Omak–Okanogan County Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ Pratt, Christine (April 11, 2013). "NCW communities named 'Tree Cities' for leafy efforts". The Wenatchee World. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ a b "Bird Watching – Heart of the Okanogan". Okanogan County Tourism Council. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Clark, Doug (March 26, 1996). "Town Tradition Goads Residents Into Donations". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ^ Mehaffey, K.C. (August 10, 2009). "Omak Stampedes New Arena Wins". The Wenatchee World. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ "History of the Omak Stampede". Stampede Association. Archived from the original on February 24, 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ Farley, Glenn (August 6, 2012). "Horse dies in qualifying round for Omak 'Suicide Race'". KING-TV. Archived from the original on March 10, 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ Smith (2004), p. 409

- ^ "Omak Stampede Arena and Grounds Redevelopment Stampede Arena Replacement – Application for Bleacher or Chair" (Doc). City of Omak. 2003. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ Timiraos, Nick (August 11, 2007). "The Race Where Horses Die". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ Johnson, Jean (September 7, 2004). "Colville's Keller Mountain tradition turns to 'Suicide Race'". Indian Country Today Media Network. New York. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ "Stop the Omak Suicide Race – Next Scheduled Cruelty: August 6 to 9, 2009 – Letters And Phone Calls Needed". In Defense of Animals. 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ "Press – Horses – Omak Suicide Race B-roll". Humane Society of the United States. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ "Wenatchee Valley College at Omak presents 9th Annual Omak Film Festival". Wenatchee Valley College. January 11, 2012. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ "Omak Film Festival features six films, begins February 8". Omak–Okanogan County Chronicle. February 8, 2008. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "Welcome To the Okanogan County Fair, Okanogan, Washington". Okanogan County Fair. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "It's time for the 75th Stampede!". Omak–Okanogan County Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 18, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ "Regions – Heart of the Okanogan". Okanogan County Tourism Council. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ "Arts & Heritage". Okanogan County Tourism Council. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ "Mirage Theater – Omak, Okanogan, Washington". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ "Omak Theater – Omak, Okanogan, Washington". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ "$50,000 Drive-In Theater to Rise". The Spokesman-Review. May 14, 1948. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ "Welcome". Omak Performing Arts Center. Archived from the original on February 25, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ Mehaffey, K.C. (January 31, 2008). "Colville Tribes to build new Omak casino in the spring". The Wenatchee World. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ "Okanogan Bingo Casino". Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. Archived from the original on July 1, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "Omak City Eastside Park". City of Omak. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ "Omak City Parks". City of Omak. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "Omak City Park Board". City of Omak. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ^ "Omak Lake/Nicholson Beach". Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ "Camping and Fishing Areas". Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ a b Liere, Alan (June 12, 2009). "Hunting + fishing". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ a b "Omak Lake Cutthroats" (PDF). Fishing Coaches. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ a b "Sunset Lakes Ranch, Omak, Washington, RV Park, Camping and Fishing". Sunset Lakes RV Park. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Quibell, Carol (July 1, 2012). "Plenty of lakes to explore around Omak, Washington". RV West. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ a b "Fishing & Hunting". Okanogan County Tourism Council. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ "Zacherle, Lewis tie for women's bowler of the month". Omak–Okanogan County Chronicle. November 20, 2007. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ "Course". Okanogan Valley Golf Club Corporation. Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ a b "Skiing/Snowboarding Areas". United States Forest Service. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ "Land Areas of the National Forest System" (PDF). United States Forest Service. January 1, 2013. Archived from the original on July 1, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- ^ "National Visitor Use Monitoring Results" (Doc). United States Forest Service. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Mehaffey, K.C. (July 19, 2011). "Proposal would add thousands of acres to wilderness". The Wenatchee World. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ "Omak Mountain". SummitPost.org. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ "Moses Mountain". SummitPost.org. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ "Omak, Okanogan, Washington to Granite Mountain, Okanogan National Forest, Conconully, Okanogan, Washington" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ "Granite Mountain Trail 1016". United States Forest Service. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ "Loup Loup Ski Bowl, Okanogan, Washington" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ "Ski the Loop". Loup Loup Ski Education Foundation. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ "Omak, Okanogan, Washington to Conconully State Park, Okanogan, Washington" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "Omak, Okanogan, Washington to Bridgeport State Park, Okanogan, Washington" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ "Omak, Okanogan, Washington to Osoyoos Lake State Park, Okanogan, Washington" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ "Omak, Okanogan, Washington to Alta Lake State Park, Okanogan, Washington" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ "Omak City RV Park". City of Omak. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ "Margie's R.V. Park, Full Hook Up, Riverside, Okanogan County". Margie's R.V. Park. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ "Omak, Washington, Campgrounds and RV Parks". CampScout.com. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Gleason, Phil. "Omak Rock Climbing". Northwest Mountaineering Journal. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Thrift, Kacie (April 17, 2013). "Chelan baseball breaks losing streak". Lake Chelan Mirror. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ Missildine, Harry (December 6, 1971). "Omak Slaughters Kettle Falls". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ "Preparation football review: Omak Pioneers". The Wenatchee World. September 2, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ Marshell, Jennifer (March 28, 2013). "Bears dominating league". Quad City Herald. Brewster. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ "Omak spikes Tigers". Omak–Okanogan County Chronicle. October 27, 2009. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ Camp, Al (January 29, 2013). "Omak tops Brewster on Pioneer senior night". Omak–Okanogan County Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ McNeil II, John (March 27, 2013). "Golfers off and swinging". The Star of Grand Coulee. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ "ATV". Okanogan County Tourism Council. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ^ "About The Omak Chronicle – (Omak, Washington) 1910–1973". Chronicling America. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "About The Omak–Okanogan County chronicle – (Omak, Washington) 1973–current". Chronicling America. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ a b "The Chronicle Online: About Us". Omak–Okanogan County Chronicle. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ "omakchronicle.com – Omak–Okanogan County Chronicle". Alexa Internet. April 1, 2013. Archived from the original on July 3, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ "The Omak–Okanogan County Chronicle – Essential Reading in Okanogan and Ferry Counties since 1910". Omak–Okanogan County Chronicle. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ DeVon, Gary. "Omak, Okanogan, Washington". Okanogan Valley Gazette–Tribune. Oroville. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ "Omak, Washington headlines". The Wenatchee World. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ Hires, Brock. "Omak, Okanogan, Washington". Okanogan Living. Tonasket. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ Mehaffey, K.C. (February 27, 2010). "Omak radio newscaster announces election bid". The Wenatchee World. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ "FM Query – FM Radio Technical Information". Federal Communications Commission. Archived from the original on August 25, 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ "KNCW Facility Record". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ "KQWS Facility Record". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ "KQWS Facility Record". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ "TV Listings – Local Broadcast (Zip Code 98841)". Zap2it. Archived from the original on April 17, 2014. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- ^ Hinman, Michael (August 28, 2009). "Seattle moves up to No. 13 U.S. TV market". Puget Sound Business Journal. Seattle. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "K17EV-D Facility Record". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "K07DG Facility Record". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "K09DG Facility Record". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "K11DM Facility Record". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "K31AH-D Facility Record". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "K19AU-D Facility Record". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "K26GV-D Facility Record". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "K08CY Facility Record". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "K10DM Facility Record". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "K12CV Facility Record". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "Current Membership Positions – 2012". North Central Washington Development District. 2012. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ "Omak City Council". City of Omak. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ^ "Omak City Municipal Code". City of Omak. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ^ "Omak City Council At Large position Two-year term". Omak–Okanogan County Chronicle. October 17, 2007. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ "Omak City Council candidates". The Wenatchee World. October 27, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ^ 2012 Final Plan adopted by the Commission and amended by the Legislature on February 7, 2012 (Map). Washington Redistricting Commission. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ "Mayor Cindy Gagne". City of Omak. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ^ "Washington State DVR – Omak Office". Washington Department of Social and Health Services. Archived from the original on April 1, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ^ "Washington City and Town Profiles". Municipal Research and Services Center. Archived from the original on November 21, 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "Omak City Council hears about hiring administrator". Omak–Okanogan County Chronicle. January 10, 2007. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- ^ "Omak City Planning Commission". City of Omak. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ a b "Omak City Library". City of Omak. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Omak City Board and Commissions". City of Omak. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ "Okanogan County, WA". National Association of Counties. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "United States Army Recruiting Office in Omak, WA". Yellow Pages. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ Matsura, Frank. "Omak Military Band, Omak, Washington, 1910". Washington State University. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ "Omak Crime Rate Report (Washington)". CityRating.com. 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ^ "Table 8 – Washington – Offenses Known to Law Enforcement by State by City, 2011" (XLS). Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2011. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ^ Mehaffey, K.C. (February 11, 2013). "88-year-old Omak man killed, vehicle stolen". The Wenatchee World. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ "Washington – Offenses Known to Law Enforcement by State by City – Historical Records". Federal Bureau of Investigation.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "Omak, WA Crime and Crime Rate – Omak, WA Crime by Year". USA.com. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ "More marijuana found growing in area". The Sun. Seattle. August 22, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- ^ "Marijuana smuggler gets 57 months in prison; Canadian used helicopter, high-tech gear; to pilot potent pot across border". The Spokesman-Review. November 2, 2001. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2013.(subscription required)

- ^ "Search for Public School Districts – District Detail for Omak School District". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ "Bond Omak School District". The Spokesman-Review. May 19, 1919. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ "Search for Public Schools – School Detail for Omak High School". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Search for Public Schools – School Detail for Omak Middle School". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Search for Public Schools – School Detail for East Omak Elementary School". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Search for Public Schools – School Detail for North Omak Elementary School". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ Schleif, Rachel (February 1, 2010). "Local schools booting up their own online offerings". The Wenatchee World. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- ^ "Search for Public Schools – School Detail for Washington Virtual Academy Omak Elementary". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Search for Public Schools – School Detail for Washington Virtual Academy Omak Middle School". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Search for Public Schools – School Detail for Washington Virtual Academy Omak High School". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Search for Private Schools – School Detail for Omak Adventist Christian School". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Veritas Classical Christian School, Omak, Okanogan, Washington" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Omak Community Library". North Central Regional Library. Archived from the original on March 10, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Omak Planning Public Library". The Spokesman-Review. July 4, 1956. Retrieved February 20, 2013.