Dolly (sheep)

Dolly (taxidermy) | |

| Other name(s) | 6LLS (code name) |

|---|---|

| Species | Domestic sheep (Finn-Dorset) |

| Sex | Female |

| Born | 5 July 1996 Roslin Institute, Midlothian, Scotland |

| Died | 14 February 2003 (aged 6) Roslin Institute, Midlothian, Scotland |

| Cause of death | Euthanasia |

| Resting place | National Museum of Scotland (remains on display) |

| Nation from | United Kingdom (Scotland) |

| Known for | First mammal cloned from an adult somatic cell |

| Offspring | 6 lambs (Bonnie; twins Sally and Rosie; triplets Lucy, Darcy and Cotton) |

| Named after | Dolly Parton[1] |

Dolly (5 July 1996 – 14 February 2003) was a female Finn-Dorset sheep and the first mammal that was cloned from an adult somatic cell. She was cloned by associates of the Roslin Institute in Scotland, using the process of nuclear transfer from a cell taken from a mammary gland. Her cloning proved that a cloned organism could be produced from a mature cell from a specific body part.[2] Contrary to popular belief, she was not the first animal to be cloned.[3]

The employment of adult somatic cells in lieu of embryonic stem cells for cloning emerged from the foundational work of John Gurdon, who cloned African clawed frogs in 1958 with this approach. The successful cloning of Dolly led to widespread advancements within stem cell research, including the discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells.[4]

Dolly lived at the Roslin Institute throughout her life and produced several lambs.[5] She was euthanized at the age of six years due to a progressive lung disease. No cause which linked the disease to her cloning was found.[6]

Dolly's body was preserved and donated by the Roslin Institute in Scotland to the National Museum of Scotland, where it has been regularly exhibited since 2003.

Genesis

Dolly was cloned by Keith Campbell, Ian Wilmut and colleagues at the Roslin Institute, part of the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, and the biotechnology company PPL Therapeutics, based near Edinburgh. The funding for Dolly's cloning was provided by PPL Therapeutics and the Ministry of Agriculture.[7] She was born on 5 July 1996.[5] She has been called "the world's most famous sheep" by sources including BBC News and Scientific American.[8][9]

The cell used as the donor for the cloning of Dolly was taken from a mammary gland, and the production of a healthy clone, therefore, proved that a cell taken from a specific part of the body could recreate a whole individual. On Dolly's name, Wilmut stated "Dolly is derived from a mammary gland cell and we couldn't think of a more impressive pair of glands than Dolly Parton's."[1]

Birth

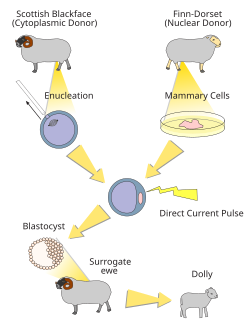

Dolly was born on 5 July 1996 and had three mothers: one provided the egg, another the DNA, and a third carried the cloned embryo to term.[10] She was created using the technique of somatic cell nuclear transfer, where the cell nucleus from an adult cell is transferred into an unfertilized oocyte (developing egg cell) that has had its cell nucleus removed. The hybrid cell is then stimulated to divide by an electric shock, and when it develops into a blastocyst it is implanted in a surrogate mother.[11] Dolly was the first clone produced from a cell taken from an adult mammal.[12][13] The production of Dolly showed that genes in the nucleus of such a mature differentiated somatic cell are still capable of reverting to an embryonic totipotent state, creating a cell that can then go on to develop into any part of an animal.[2]

Dolly's existence was announced to the public on 22 February 1997.[1] It gained much attention in the media. A commercial with Scottish scientists playing with sheep was aired on TV, and a special report in Time magazine featured Dolly.[7] Science featured Dolly as the breakthrough of the year. Even though Dolly was not the first animal cloned, she received media attention because she was the first cloned from an adult cell.[14]

Life

Dolly lived her entire life at the Roslin Institute in Midlothian.[15] There she was bred with a Welsh Mountain ram and produced six lambs in total. Her first lamb, named Bonnie, was born in April 1998.[5] The next year, Dolly produced twin lambs Sally and Rosie; further, she gave birth to triplets Lucy, Darcy and Cotton in 2000.[16] In late 2001, at the age of four, Dolly developed arthritis and started to have difficulty walking. This was treated with anti-inflammatory drugs.[17]

Death

On 14 February 2003, Dolly was euthanised because she had a progressive lung disease and severe arthritis.[6] A Finn Dorset such as Dolly has a life expectancy of around 11 to 12 years, but Dolly lived 6.5 years. A post-mortem examination showed she had a form of lung cancer called ovine pulmonary adenocarcinoma, also known as Jaagsiekte,[18] which is a fairly common disease of sheep and is caused by the retrovirus JSRV.[19] Roslin scientists stated that they did not think there was a connection with Dolly being a clone, and that other sheep in the same flock had died of the same disease.[6] Such lung diseases are a particular danger for sheep kept indoors, and Dolly had to sleep inside for security reasons.[20]

Some in the press speculated that a contributing factor to Dolly's death was that she could have been born with a genetic age of six years, the same age as the sheep from which she was cloned.[21] One basis for this idea was the finding that Dolly's telomeres were short, which is typically a result of the aging process.[22][23] The Roslin Institute stated that intensive health screening did not reveal any abnormalities in Dolly that could have come from advanced aging.[21]

In 2016, scientists reported no defects in thirteen cloned sheep, including four from the same cell line as Dolly. The first study to review the long-term health outcomes of cloning, the authors found no evidence of late-onset, non-communicable diseases other than some minor examples of osteoarthritis and concluded "We could find no evidence, therefore, of a detrimental long-term effect of cloning by SCNT on the health of aged offspring among our cohort."[24][25]

After her death Dolly's body was preserved via taxidermy and is currently on display at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.[26]

Legacy

After cloning was successfully demonstrated through the production of Dolly, many other large mammals were cloned, including pigs,[27][28] deer,[29] horses[30] and bulls.[31] The attempt to clone argali (mountain sheep) did not produce viable embryos. The attempt to clone a banteng bull was more successful, as were the attempts to clone mouflon (a form of wild sheep), both resulting in viable offspring.[32] The reprogramming process that cells need to go through during cloning is not perfect and embryos produced by nuclear transfer often show abnormal development.[33][34] Making cloned mammals was highly inefficient – in 1996, Dolly was the only lamb that survived to adulthood from 277 attempts. By 2014, Chinese scientists were reported to have 70–80% success rates cloning pigs,[28] and in 2016, a Korean company, Sooam Biotech, was producing 500 cloned embryos a day.[35] Wilmut, who led the team that created Dolly, announced in 2007 that the nuclear transfer technique may never be sufficiently efficient for use in humans.[36]

Cloning may have uses in preserving endangered species, and may become a viable tool for reviving extinct species.[37] In January 2009, scientists from the Centre of Food Technology and Research of Aragon in northern Spain announced the cloning of the Pyrenean ibex, a form of wild mountain goat, which was officially declared extinct in 2000. Although the newborn ibex died shortly after birth due to physical defects in its lungs, it is the first time an extinct animal has been cloned, and may open doors for saving endangered and newly extinct species by resurrecting them from frozen tissue.[38][39]

In July 2016, four identical clones of Dolly (Daisy, Debbie, Dianna, and Denise) were alive and healthy at nine years old.[40][41]

Scientific American concluded in 2016 that the main legacy of Dolly has not been cloning of animals but in advances into stem cell research.[42] Gene targeting was added in 2000, when researchers cloned female lamb Diana from sheep DNA altered to contain the human gene for alpha 1-antitrypsin. The human gene was specifically activated in the ewe’s mammary gland, so Diana produced milk containing human alpha 1-antitrypsin.[43] After Dolly, researchers realised that ordinary cells could be reprogrammed to induced pluripotent stem cells, which can be grown into any tissue.[44]

The first successful cloning of a primate species was reported in January 2018, using the same method which produced Dolly. Two identical clones of a macaque monkey, Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua, were created by researchers in China and were born in late 2017.[45][46][47][48]

In January 2019, scientists in China reported the creation of five identical cloned gene-edited monkeys, again using this method, and the gene-editing CRISPR-Cas9 technique allegedly used by He Jiankui in creating the first ever gene-modified human babies Lulu and Nana. The monkey clones were made in order to study several medical diseases.[49][50]

See also

- In re Roslin Institute (Edinburgh) – US court decision that determined that Dolly could not be patented

References

- ^ a b c "1997: Dolly the sheep is cloned". BBC News. 22 February 1997. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ a b Niemann H; Tian XC; King WA; Lee RS (February 2008). "Epigenetic reprogramming in embryonic and foetal development upon somatic cell nuclear transfer cloning" (PDF). Reproduction. 135 (2): 151–63. doi:10.1530/REP-07-0397. PMID 18239046. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ "The Life of Dolly | Dolly the Sheep". Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ "The Legacy | Dolly the Sheep". Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ a b c "Dolly the sheep clone dies young" Archived 12 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. 14 February 2003

- ^ a b c Dolly's final illness Archived 27 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine Roslin Institute, Accessed 21 February 2008 Archived 30 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Edwards, J. (1999). "Why dolly matters: Kinship, culture and cloning". Ethnos. 64 (3–4): 301–324. doi:10.1080/00141844.1999.9981606.

- ^ "Is Dolly old before her time?". BBC News. London. 27 May 1999. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ Lehrman, Sally (July 2008). "No More Cloning Around". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- ^ Williams, N. (2003). "Death of Dolly marks cloning milestone". Current Biology. 13 (6): 209–210. Bibcode:2003CBio...13.R209W. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00148-9. PMID 12646139.

- ^ Campbell KH; McWhir J; Ritchie WA; Wilmut I (1996). "Sheep cloned by nuclear transfer from a cultured cell line". Nature. 380 (6569): 64–6. Bibcode:1996Natur.380...64C. doi:10.1038/380064a0. PMID 8598906. S2CID 3529638.

- ^ McLaren A (2000). "Cloning: pathways to a pluripotent future". Science. 288 (5472): 1775–80. doi:10.1126/science.288.5472.1775. PMID 10877698. S2CID 44320353.

- ^ Wilmut I; Schnieke AE; McWhir J; Kind AJ; et al. (1997). "Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells". Nature. 385 (6619): 810–3. Bibcode:1997Natur.385..810W. doi:10.1038/385810a0. PMID 9039911. S2CID 4260518.

- ^ McKinnell, Robert G.; Di Berardino, Marie A. (November 1999). "The Biology of Cloning: History and Rationale". BioScience. 49 (11): 875–885. doi:10.2307/1313647. JSTOR 1313647.

- ^ Kolata, Gina (14 February 2003). "Dolly, the First Cloned Mammal, Is Dead". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Dolly's family. Roslin Institute, UK

- ^ Dolly's arthritis. Roslin Institute, Accessed 21 February 2008

- ^ Bridget M. Kuehn Goodbye, Dolly; first cloned sheep dies at six years old Archived 4 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine American Veterinary Medical Association, 15 April 2003

- ^ Palmarini M (2007). "A Veterinary Twist on Pathogen Biology". PLOS Pathog. 3 (2): e12. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030012. PMC 1803002. PMID 17319740.

- ^ Kolata, Gina (15 February 2003). "First Mammal Clone Dies; Dolly Made Science History". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ a b Was Dolly already 'old' at birth? Archived 28 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine Roslin Institute, Accessed 4 April 2010

- ^ Shiels PG; Kind AJ; Campbell KH; et al. (1999). "Analysis of telomere length in Dolly, a sheep derived by nuclear transfer". Cloning. 1 (2): 119–25. doi:10.1089/15204559950020003. PMID 16218837.

- ^ Shiels PG; Kind AJ; Campbell KH; et al. (1999). "Analysis of telomere lengths in cloned sheep". Nature. 399 (6734): 316–7. Bibcode:1999Natur.399..316H. doi:10.1038/20580. PMID 10360570. S2CID 4380715.

- ^ Sinclair, K. D.; Corr, S. A.; Gutierrez, C. G.; Fisher, P. A.; Lee, J.-H.; Rathbone, A. J.; Choi, I.; Campbell, K. H. S.; Gardner, D. S. (26 July 2016). "Healthy ageing of cloned sheep". Nature Communications. 7: 12359. Bibcode:2016NatCo...712359S. doi:10.1038/ncomms12359. PMC 4963533. PMID 27459299.

- ^ Klein, Joanna (26 July 2016). "Dolly the Sheep's Fellow Clones, Enjoying Their Golden Years". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ "Dolly the Sheep's fleece donated to museum". BBC News. 24 December 2023. Archived from the original on 24 December 2023. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ Grisham, Julie (April 2000). "Pigs cloned for first time". Nature Biotechnology. 18 (4): 365. doi:10.1038/74335. PMID 10748477. S2CID 34996647.

- ^ a b Shukman, David (14 January 2014) China cloning on an 'industrial scale' Archived 17 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, Retrieved 14 January 2014

- ^ "Texas A&M scientists clone world's first deer". Innovations Report. 23 December 2003. Archived from the original on 11 November 2006. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ Cohen, Haley (31 July 2015). "How Champion-Pony Clones Have Transformed the Game of Polo". VFNews. Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Lozano, Juan A. (27 June 2005). "A&M Cloning project raises questions still". Bryan-College Station Eagle. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ "Endangered sheep cloned". BBC News. London. 1 October 2001. Archived from the original on 24 January 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ^ Jaenisch R; Hochedlinger K; Eggan K (2005). "Nuclear Cloning, Epigenetic Reprogramming and Cellular Differentiation". Stem Cells: Nuclear Reprogramming and Therapeutic Applications. Novartis Foundation Symposia. Vol. 265. pp. 107–18, discussion 118–28. doi:10.1002/0470091452.ch9. ISBN 978-0-470-09145-6. PMID 16050253.

- ^ Rideout WM; Eggan K; Jaenisch R (August 2001). "Nuclear cloning and epigenetic reprogramming of the genome". Science. 293 (5532): 1093–8. doi:10.1126/science.1063206. PMID 11498580. S2CID 23021886.

- ^ Zastrow, Mark (8 February 2016). "Inside the cloning factory that creates 500 new animals a day". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Roger Highfield "Dolly creator Prof Ian Wilmut shuns cloning" Archived 16 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Daily Telegraph 16 November 2007

- ^ Trounson AO (2006). "Future and Applications of Cloning". Nuclear Transfer Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 348. pp. 319–32. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-154-3_22. ISBN 978-1-58829-280-3. PMID 16988390. Archived from the original on 9 June 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ Gray, Richard; Dobson, Roger (31 January 2009). "Extinct ibex is resurrected by cloning". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2009.

- ^ Jabr, Ferris (11 March 2013). "Will Cloning Ever Save Endangered Animals?". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ "Clones da ovelha Dolly envelheceram com boa saúde, diz estudo" (in Portuguese). Rede Globo. 26 July 2016. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ "Dolly the sheep's siblings 'healthy'". News – Science and Environment. BBC. 26 July 2016. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ Weintraub, Karen. "20 Years after Dolly the Sheep Led the Way—Where Is Cloning Now?". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ Adam, David (29 June 2000). "Science of the lambs". Nature. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. doi:10.1038/news000629-8. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Sample, Ian (26 July 2016). "Dolly's clones ageing no differently to naturally-conceived sheep, study finds". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ Liu, Zhen; et al. (24 January 2018). "Cloning of Macaque Monkeys by Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer". Cell. 172 (4): 881–887.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.020. PMID 29395327.

- ^ Normile, Dennis (24 January 2018). "These monkey twins are the first primate clones made by the method that developed Dolly". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aat1066. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Briggs, Helen (24 January 2018). "First monkey clones created in Chinese laboratory". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Scientists Successfully Clone Monkeys; Are Humans Up Next?". The New York Times. Associated Press. 24 January 2018. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Science China Press (23 January 2019). "Gene-edited disease monkeys cloned in China". EurekAlert!. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Ryan F. (23 January 2019). "China's Latest Cloned-Monkey Experiment Is an Ethical Mess". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

External links

- Dolly the Sheep at the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh

- Cloning Dolly the Sheep Dolly the Sheep and the importance of animal research

- Animal cloning and Dolly

- Antiques Roadshow, Series 45, Brodie Castle 3, Dolly the Sheep. BBC (3' video clip). 6 April 2023. Episode where several items appertaining to Dolly, including wool from a shearing and scientific instruments, were appraised.

- 1996 animal births

- 2003 animal deaths

- 1996 in biotechnology

- 1996 in Scotland

- 2003 in Scotland

- Animal world record holders

- Cloned sheep

- Cloning

- Individual animals in the United Kingdom

- Collection of National Museums Scotland

- History of Midlothian

- Dolly Parton

- Individual animals in Scotland

- Individual taxidermy exhibits