Docklands, Victoria

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2023) |

| Docklands Melbourne, Victoria | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

View toward Docklands, including Docklands Stadium, October 2017 | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°49′01″S 144°56′46″E / 37.817°S 144.946°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 15,495 (2021 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 5,200/km2 (13,400/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 21st century | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 3008 | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 7 m (23 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 3 km2 (1.2 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | 2 km (1 mi) from Melbourne CBD | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Melbourne | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | |||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

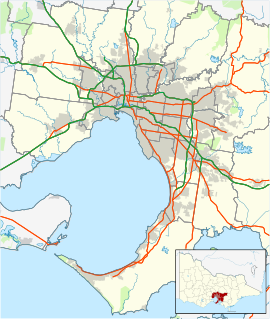

Docklands, is an inner-city suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia on the western end of the central business district. Docklands had a population of 15,495 at the 2021 census.

Primarily a waterfront area centred on the banks of the Yarra River, it is bounded by Spencer Street, Wurundjeri Way and Montague Street to the east, the Yarra River and Moonee Ponds Creek to the west, Footscray Road and Dynon Road to the north and Lorimer Street, Boundary Road and the West Gate Freeway across the Yarra River to the south.

The site of modern-day Docklands was originally swamp land that in the 1880s became a bustling dock area as part of the Port of Melbourne, with an extensive network of wharfs, heavy rail infrastructure and light industry. Following the containerisation of shipping traffic, Docklands fell into disuse and by the 1990s was virtually abandoned, making it the focal point of Melbourne's underground rave scene.[2] The construction of Docklands Stadium in the late 1990s attracted developer interest in the area, and urban renewal began in earnest in 2000 with several independent privately developed areas overseen by VicUrban, an agency of the Victorian Government. Docklands subsequently experienced an apartment boom and became a sought-after business address,[3] attracting the national headquarters of, among others, the National Australia Bank, ANZ Bank, Myer, David Jones, Medibank and the Bureau of Meteorology, as well as the regional headquarters for Ericsson, Bendigo & Adelaide Bank and television networks Nine and Seven.[4]

Known for its contemporary architecture, the suburb is home to a number of heritage buildings that have been retained for adaptive reuse, and is also the site of landmarks such as the Docklands Stadium, Southern Cross railway station and the Melbourne Star.

Although still incomplete, Docklands' developer-centric planning has split public opinion with some lamenting its lack of green open space,[5] pedestrian activity, transport links and culture.[6][7][8]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

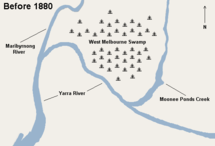

Before the foundation of Melbourne, it was a large wetlands area of the Yarra River estuary consisting of a large salt water lagoon and a giant swamp at the mouth of the Moonee Ponds Creek. It was one of the open hunting grounds of the Wurundjeri people, who created middens around the edges of the lake. The lake was populated by fauna including native black swans and wild ducks as well and earlier, with its connection to Hobsons Bay, such marine life as snapper and swordfish.[9][10]

In 1835, Vandemonian John Batman established a home on Batman's Hill, marking the westernmost point of a new settlement. The rest of the area, however, remained largely unused for decades. The swamp, known as Batman's Swamp, and later West Melbourne Swamp was a major source of nuisance to the colony, considered ugly and unsanitary and produced a strong unpleasant smell.[11]

The first plans to reclaim the swamp issue were presented on 5 May 1858 by engineer Alexander Kennedy Smith to the Philosophical Institute of Victoria and proposed a system of three canals and a road to Footscray.[11] While the reclamation did not proceed, the road did. Swamp Road (now Dynon Road) was completed in 1863 and included two bridges across the north of the lagoon.[12]

The advent of rail infrastructure in the late 1860s saw the city's industry gradually expand into the area. By 1878, Moonee Ponds Creek became a series of drainage canals with a system of bluestone constructions helping to funnel the salty water further south.[10]

The earliest extensive plans to develop the area was in the 1870s, when a plan was prepared to extend the Hoddle Grid westward, following the curve of the Yarra River and effectively doubling its size. The plan proposed several gridlike blocks with an ornamental public garden and lake in the shape of the United Kingdom, occupying the site of the salt lake. However, expansion of the grid westward was abandoned in favor of a northward extension.

Construction of Victoria Dock

[edit]Under the guidance of British civil engineer John Coode, a major engineering project began in the 1880s to reroute the course of the Yarra River, which resulted in the widening of the river for shipping and the creation of a new Victoria Dock (the name was previously used by one at Queens Bridge as early as the 1850s). The dock was lined with wharves and light industry grew around the nearby western rail yards of Spencer Street railway station (now Southern Cross railway station), which were used for freighting the goods inland.

Early to mid 20th century: From West Melbourne swamp to slum and new shipping port

[edit]

During the wars, Victoria Dock was used as the main port for naval vessels and most of the Victorian troops returned from both wars to the docks.

In 1924 the Victorian Railways engineer Edward Ballard prepared designs for a new freight yards including a new Melbourne Yard and Spencer Street Yard and West Melbourne Dock (later Victoria Harbour) and an extension of Dudley Street westward and a new main road through West Melbourne which would later become Docklands Highway with land to be transferred to the Melbourne Harbour Trust.[13]

During the Great Depression era, the area along Moonee Ponds Creek was home to a large rubbish tip. Just across the creek (near the site of Costco) were Dudley Mansions, a notorious slum of half a dozen homes constructed from refuse which Frederick Oswald Barnett began photographing and actively campaigning against.[14]

Construction of the new Victoria Harbour took place over the following decades and with shipping was moved from the Yarra turning basin at Queensbridge Victoria Dock became Melbourne's busiest.

Disuse and rave epicentre

[edit]With the introduction of containerisation of Victoria's shipping industry in the 1950s and 1960s, the docks along the Yarra River, east of the modern Bolte Bridge, and within Victoria Harbour immediately to the west of the central business district, became inadequate for the new container ships.

The creation of Appleton Dock and Swanson Dock in an area west of the Moonee Ponds Creek, now known as West Melbourne, closer to the mouth of the Yarra, became the focus of container shipping, effectively rendering redundant a vast amount of vacant inner-city land to the immediate west of Melbourne's CBD.

Docklands became notable during the 1990s for its underground rave dance scene.[2] The growth of the warehouse rave scene carried on from the earlier gay and lesbian warehouse party scene which had started in the early 1980s, and continued in the Docklands through parties such as The ALSO Foundation's Red Raw, Winterdaze, New Year's Eve, and Resurrection dance parties.

The site was also host to a number of dance parties by Future Entertainment and Hardware Corporation. DJs and performers such as Paul van Dyk, Carl Cox, Jeff Mills, Frankie Knuckles, David Morales, Marshall Jefferson and BT headlined these events. The biggest event hosted, in terms of attendance, was the "Welcome 2000" New Year's Eve dance party hosted on 31 December 1999.

Urban renewal

[edit]Docklands was seen as a large urban blight by the Cain Jr. State Government. Property consultants JLW Advisory carried out the first market demand assessment of the site.[15]

The size of the Melbourne Docklands area meant that political influences were inescapable. The Docklands project was on top of the government's agenda,[16] however, due to the poor condition of the wharf infrastructure, a further investment was required to initiate the project, which the government at the time could not afford. Nevertheless, the Docklands project stayed on the drawing board, but with little progress. In 1989, several architectural firms were invited to discuss how the area could best serve the Melbourne public.

In 1990, the Docklands Task Force was established to devise an infrastructure strategy and conduct the public consultation process.[16] The Committee For Melbourne, a not for profit organization that brought together the private sector of Melbourne for a public good, was pursuing another planning strategy. It involved a bid for the 1996 Olympic Games and another proposal to turn the Docklands into a technology city, known as the Multifunction Polis (MFP). Both bids fell through in late 1990.[16] Nevertheless, the Committee For Melbourne's approach became the preferred model in the proceeding strategies for the Docklands development, leading to the formation of the Docklands Authority in July 1991.[16]

Kennett era and ARM Masterplan

[edit]With a government running in budget deficits, not much progress was made on the Docklands project. In late 1992, Jeff Kennett was elected Premier. Kennett instituted many changes and turned the government's financial position around. He then embarked on a multitude of projects, which included Docklands. It was politically imperative to get the project rolling, the Docklands Authority opted for the concept of having infrastructure funded by the developers. The development industry supported this, and claimed that the project would be more efficient. Docklands was divided into sections or precincts, which were to be tendered to private companies to be developed.

May 1996 saw the relaunch of the tender process. Few restrictions were applied to the bids from developers, and as the vision was to make Docklands 'Melbourne's Millennium Mark', the key criterion for a successful bid was to get projects going by 2000.[16] It did not take long for the realisation that the lack of government coordination in infrastructure planning would create problems. Developers would not invest into public infrastructure, where benefits would flow on to an adjacent property. This was corrected by allowing developers to negotiate for infrastructure funding with the government. The Docklands Village precinct was planned for a residential and commercial mixed development, but, in late 1996, that plan was scrapped when it was announced a private football stadium would be built on the site.[16] The site was chosen for its easy access to the then Spencer Street station (now Southern Cross station), and it was intended to be an anchor for the entire project and provide for a clear signal to the long-awaited start of the Docklands project. However, the stadium also created a huge barrier between the City and Docklands.

Work on the Bolte Bridge, designed by architects Denton Corker Marshall, for Transurban and constructed by Baulderstone Hornibrook, another architectural centrepiece took place from 1996 to 1999 and costing $75 million.

In 1997, the Docklands commission engaged architects Ashton Raggatt McDougall (ARM) to design the Docklands masterplan incorporating the stadium, Victoria Dock and the Yarra on both sides of the Bolte Bridge. The whimsical futuristic design featured mostly curvy building frontages and winding thoroughfares. The centrepiece was an oval shaped central park (approximately the size of the Docklands Stadium field) accessed via a network of footbridges and surrounded by mid-sized towers from which a radial network of roads were lined by irregular curved footprints, each individually surrounded by zig-zagging lines of trees along the parks and open space. Vehicular traffic was minimised by a reduced road connectivity to encourage pedestrianisation. Harbour Esplanade was to be lined by low-rise commercial buildings such as restaurants to attract activity to the foreshore. The original plan featured integrated windbreaks to reduce the wind-tunnel effect. A wide promenade and framed park would directly connect Bourke Street and Lonsdale Streets to the new precinct (the present site of Southern Cross Station), effectively funnelling pedestrians from the CBD toward the new waterfront. Moonee Ponds Creek was connected to Victoria Dock via a winding channel creating additional waterfront and the precincts were dotted by small irregularly placed ponds, islands and boardwalks. Another small channel would have connected the Victoria Harbour waterway with the Yarra to the south allowing for more flow and less stagnant water. Central Pier was to be demolished and replaced by a peninsula of connected islands featuring green space and a walking path from which the whole precinct could be viewed. Moonee Ponds Creek would have been restored featuring a peninsula extending beyond the present Bolte Bridge adding a large park to the northern riverside frontage of the precinct.

Bracks/Brumby era: Redesign and Commencement of Construction (1998)

[edit]

With the exception of Yarra Waters (later Yarra's Edge) bid by Mirvac, bid for every other precinct between 1998 and 1999 fell through, reasons for which were often unclear due to secrecy provisions[16] and a change of government.

Under a new government the ARM masterplan was largely abandoned for a new Docklands Public Realm Plan and a new planning committee was established in conjunction with the City of Melbourne. This new plan removed the wavy original masterplan in favour of a largely rectilinear plan. Significantly the new masterplan removed key pedestrian connections to the CBD at Lonsdale Street and called for an elevated concrete footbridge via Bourke Street, effectively isolating the northern parts of the precinct from the CBD (due to plans for the new Southern Cross Station). The large public plaza proposed on the railyards between Bourke and Lonsdale Street was excluded leaving a large and visually unappealing space which disconnects Docklands from the CBD. Instead of reducing the connections to the road network, a new north–south highway, Wurundjeri Way, would further bisect the precinct and disconnect it from the CBD. The new plan called for much taller, more built up areas of towers along the north and south of the harbour and toward the Hoddle Grid (present sites of New Quay and Yarra's Edge and Batman's Hill). Central pier was to be restored and retained instead of demolished. Many more marinas catered for more private boats at New Quay, Victoria Harbour and Yarra's Edge than the original design, further reducing the amount of open water. Green space around the smaller and mid-sized buildings was removed in favour of footprints built to street frontage with laneways connecting each street between shorter podiums. More traditional avenues of street trees replaced irregular plantings, the ornamental ponds and floating walkways were removed in favour of long linear concrete promenades. Mixed-use low-rise along Harbour Esplanade which was aimed to increase activity along the foreshore was removed in order to widen the main thoroughfare. Docklands Park became a linear park flanked by shorter towers aligned north south with the Charles Grimes Bridge. Moonee Ponds Creek extension and restoration was also removed from the masterplan. The design also called for a wide Harbour Esplanade with no buildings along its foreshore lined by Canary Island Date Palms similar to the popular foreshores of Port Melbourne and Albert Park.[17]

Through the tendering process for the sites, the business park was split once more and awarded to two consortia, becoming Entertainment City (renamed Paramount Studios) - a movie theme park with film studios, to be developed by a Viacom led consortium, and Yarra Nova (which later evolved into NewQuay), to the MAB Corporation consortium. The Paramount Studios proposal fell through, and the site was put to tender once more, as Studio City, and later awarded as two parts, becoming what is now Docklands Studios Melbourne and Waterfront City.

Yarra Waters/Yarra Quays was awarded to Mirvac, later becoming Yarra's Edge.

The technology park was renamed Commonwealth Technology Port (or Comtech Port) before finally becoming Digital Harbour.

A number of other sites also encountered false starts, with Victoria Harbour originally being awarded to Walker Corporation, before being put out to tender again and finally being awarded to Lendlease in April 2001. The Batman's Hill precinct was originally awarded to Grocon, which had plans for what would have been the world's tallest building rising 560 m, dubbed Grollo Tower and featuring a mix of office, apartment, hotel and retail. This deal also fell through with the site being subdivided into 15 parcels as well as No 2 Goods Shed.

On 1 July 2007 Docklands became part of the City of Melbourne Local Government Authority, however, VicUrban retained planning authority until 2010.

Districts

[edit]Following the initial Vicurban tender and the 1999 masterplan, Docklands was divided the land into a number of themed precincts, with each to be designed and built by a different development company. Overall governance was overseen by the Docklands Authority. The precincts defined (from north to south) were:

| District | Proposed use | Land area | Initially granted to |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waterfront City | Mixed-use commercial | Area from Footscray Road south to Docklands Drive | ING Real Estate |

| Commonwealth Technology Port (now Digital Harbour) | Technology Park | Area to the west between Harbour Esplanade and Wurundjeri Way | Digital Harbour Holdings |

| New Quay | Mixed use (primarily residential) | Area along the north shoreline of the Victoria Docks | MAB Corporation |

| Central Pier | Restaurant precinct | Heritage registered Central Pier, Victoria Dock | Victorian government |

| Stadium Precinct | Mixed use | Land around the Docklands Stadium up to Wurundjeri Way | Divided into 4 sections - NWSP was awarded to Channel 7/Pacific Holdings (NSWP), Pan Urban (NESP), Devine Limited/RIA Property Group (SWSP), Bourke Junction Consortium (ISPT, Cbus Property and EPC Partners) (SESP) |

| Victoria Harbour | Office/Mixed use | From the south of Victoria Dock to the Yarra River to Wurundjeri Way with Collins Street and Bourke Street extended and planned to meet | Lendlease |

| Batman's Hill | Office/Mixed use | West of Harbour Esplanade and south of Bourke Street to the Yarra River connecting Docklands to the Hoddle grid including an extension of Collins Street | Walker Corporation (Collins Square) and Lendlease (Melbourne Quarter) |

| Yarra's Edge | Residential/Mixed use | Area along the southern shoreline of the Yarra north of Lorimer Street | Mirvac |

Since the initial tendering process, other precincts and sub-precincts within these have emerged.

Northbank

[edit]

Though not part of the 1999 masterplan or tendering process, the area of Docklands north of the Yarra opposite South Wharf from Spencer Street to Charles Grimes Bridge area around Siddeley Street originally including the part of North Wharf closest to the Hoddle grid is part of the gazetted land. It was rebranded as the Northbank precinct as other parts of Docklands began construction. At the time it consisted of a collection of a handful of existing buildings. Originally home to 1880s markets and industry including the Mission to Seamen building, between the 1920s and 1940s the area was almost completely cleared for a new port including Goods Shed number 5 and a large electric crane. By the 1970s, the majority of the area was covered by a parking lot with a petrol station and a small number of commercial buildings remaining from the 1920s era.

In the late 1970s, the disused port area was first earmarked for urban renewal aimed at extending CBD beyond the Hoddle grid along the river past Spencer Street. A small cluster of 1920s commercial buildings were cleared to construct the brutalist landmarks the blocky World Trade Center (1982) and semi-circular shaped Crowne Plaza Hotel (1988) along with a massive multi-storey carpark, Melbourne's largest at the time, aimed to attract motorist commuters. However without permanent residents, like much of the CBD in the 80s the area proved unpopular and failed to attract activity despite the opening of Melbourne's Melbourne's first casino there, Crown Casino in 1994 and after its 1997 relocation to the permanent new site in Southbank, a temporary Madame Tussauds wax museum. Due to the precincts initial failure, development subsequently halted for over a decade.

Since the Docklands project the area has seen a growth of new interest in the long neglected precinct with over $1 billion in planned development. Flinders Wharf (2003) was one of the first new developments, adding 301 hi-rise apartments and mixed use to the riverfront. Relocation of Victoria Police headquarters to the World Trade Center offices and establishing a new police museum in 2007 was followed by redevelopment of the World Trade Centre as WTC Wharf (2008) aimed at stimulating further investment in the precinct. Mirvac have constructed a 20-storey office tower at 7 Spencer Street (2021).[18] Melbourne Skyfarm (2021-23), a greening of the roof of the multi-storey carpark including sustainability centre, was aimed at softening the mostly harsh concrete area. 637 Flinders (2022) by Cox Architecture is seven storey modern infill office building added to the provide street frontage to the shorter World Trade Centre tower. Seafarers (2024), a mixed-use apartment building by architects Fender Katsalidis included a new public park known as Seafarers Rest and restaurants along a reconstructed Goods Shed 5.[19]

Northbank is also a key part of the Greenline pedestrian and cycling link aimed at connecting Melbourne to the Docklands along the Yarra.

Batman's Hill

[edit]

The Batman's Hill precinct is an 100,000 square metre area bordered by the Yarra River to the south, Spencer Street to the east, Docklands Stadium to the north and Victoria Harbour to the west. The precinct is named after the historical landmark Batman's Hill, which was once located within the area.

It is a mixed-use precinct including commercial and retail space, entertainment, hotels, residential sections, restaurants, cultural sites and educational institutions as well as the historic Rail Goods Shed No. 2, which was split in half to allow for the extension of Collins Street into Docklands, providing businesses with an address that is considered to be prestigious.

Fox Classic Car Museum in the Queens Warehouse was one of the first places to open in Batman's Hill in 2000.

Completed buildings include:

- 700 Collins Street (home to the Bureau of Meteorology and Medibank) (2003)

- 750 Collins Street (the Melbourne headquarters of AMP) (2007)

- Watergate apartments and small office complex (2007)

- 737 Bourke Street (10 storey office building for headquarters of National Foods) (2008)

- Media House (2010) at 643 Collins Street. Built for Fairfax Media it comprises 16,000 m2 of office space accommodating 1,400 staff, on decking over railway lines opposite Southern Cross Station. The $110 million eight-storey facility was designed by architects Bates Smart to achieve a 5-star Green Star rating, and features a news ticker, outdoor screen and grassy plaza. It was developed by Grocon in 2009.[20]

- 717 Bourke Street (17 storey building consisting of a 294-room Travelodge Hotel) (2011)

- Kangan Institute's Automotive Centre for Excellence (ACE) (2023)

On 2 August 2007, it was reported that a $1.5 billion scheme had been earmarked for Collins Street by Middle Eastern investment company Sama Dubai, to be designed by architect Zaha Hadid and Melbourne firm Ashton Raggatt McDougall. The plan would consist of four buildings, including Docklands' tallest tower as well as civic spaces spanning two sites to be built on decking over Wurundjeri Way. The proposed tower would have between 50 and 60 storeys tall but did not proceed and VicUrban put the site back out to tender in early 2011.[21]

Collins Square

[edit]

Collins Square (previously Village Docklands) is a ~2Ha site within the Batman's Hill precinct. It was developed by Walker Corporation.

Collins Square is the outcome of a split of precincts in the tender process in 2000, which resulted in Goods Shed South, 735 Collins Street and Sites 4A-4F, originally awarded to the Kuok Group and Walker Corporation.

A masterplan prepared by Marchese + Partners in conjunction with Bligh Voller Nield architects was approved in early 2002. It included a 60-storey Shangri-La Hotels and Resorts tower with a Collins Street address and a mix of commercial and residential towers, as well as the refurbishment of the southern half of Goods Shed No. 2 into a night market and food hall.

In mid-2007, a new masterplan was prepared by Bates Smart. In it a new 38-storey office tower replaced the Shangri La Hotel on Collins Street and the number of streets is reduced from four to three, replaced by pedestrian thoroughfares. Overall there will now be five office buildings, ranging in height from 155m (to roof) to 36m, a 10,000sqm retail and public space, and the refurbishment of the Goods Shed with a 'Lantern' structure addressing Collins Street. The entire precinct is aiming for a 5 Star Green Star rating.

Construction of Collins Square was completed in 2018.

Stadium Precinct

[edit]

The Stadium Precinct, which sits on the eastern edge of Docklands, consists of Docklands Stadium, Seven Network's Melbourne digital broadcasting centre, Victoria Point, Bendigo Bank offices, Medibank offices and serviced apartments. It is linked to Southern Cross station and the Melbourne CBD by the Bourke Street pedestrian bridge, built over railway lines.

During the 2000 Docklands development tender process, the stadium precinct was divided into four corners, the North West Stadium Precinct (NWSP), North East Stadium Precinct (NESP), South East Stadium Precinct (SESP) and South West Stadium Precinct (SWSP). The NWSP was awarded to Channel 7/Pacific Holdings. The NESP was awarded to Pan Urban. The SWSP was awarded to Devine Limited/RIA Property Group and the SESP - Bourke Junction Consortium (ISPT, CBUS Property and EPC Partners).

Docklands Stadium (originally Colonial Stadium) was opened in March 2000. The ability for the structure to have both open and closed roof configurations has seen it host many sports events, including Australian Rules Football, soccer, cricket and rugby as well as concerts. The stadium complex is currently managed by Stadium Operations Ltd, which is owned by the Seven Network, with ownership transferring to the Australian Football League in 2025.

Developer Pan Urban has announced plans for a $300 million twin-tower apartment development, known as Lacrosse Docklands, for the NESP, with the towers set to rise 21 and 18 storeys respectively, above the stadium concourse, with restaurants and bars opening out on to the concourse, forming a retail plaza.[22]

Plans for the site to be known as Bourke Junction include office towers of 29 and 21 storeys on the north-eastern and south-western corners of the SESP site, as well as three lower-rise buildings housing a 250-room hotel, a pub, medical centre, retail facilities, a business club and a two-level gymnasium.[23]

Harbour Esplanade and stadium redevelopments (2010-)

[edit]

Due to concerns over the failed pedestrian activation of Harbour Esplanade, it was redeveloped between 2010 and 2011 at a cost of $9.2 million. The existing 23 10 metre tall palms and gum trees were replaced by 230 Norfolk Island pines (for a more stronger windbreak effect), realigned tram tracks to the centre roadway and new separated bicycle paths added.[24] However the redevelopment failed in its objective to increase pedestrian activation of the foreshore. As a result, another $16 million redevelopment under a new Harbour Esplanade Masterplan was proposed to repair the degraded wharfs unsuitable for pedestrian activation and reinstate previously demolished sheds and introduce an avenue trees to the waterfront.[25] In 2020 the heritage listed Central Pier and its Shed 9 and Shed 19 were permanently closed due to its deteriorating condition. By 2023 the government decided to demolish and replace the heritage listed Central Pier which had been a centrepiece of the revised 1999 masterplan. The project would cost a total of $550 million.[26][27] The shutdown was estimated to cost a further $865 million to the economy and was the subject of legal action against the government by commercial tenants.[28] In 2024 an additional $225 was committed by the government to redevelop the stadium in an attempt to activate the foreshore.[29]

Digital Harbour at Comtechport Precinct

[edit]

Digital Harbour is a waterfront that has an area of 44,000 square metres, with development intended to expand to include 220,000 square metres of commercial, residential, SOHO units and retail space. At present only three buildings have been completed; 1010 LaTrobe Street/Port 1010 (home to VicTrack, Australian Customs and Border Protection Service), and the Innovation Building (home of the Telstra Learning Academy and Innovation Centre). A third building, Life.lab currently resides at 198 Harbour Esplanade, while a fourth, 1000 La Trobe Street, is expected to commence shortly.

Port 1010 received the Commercial Architecture Award at the 2007 Victorian Architecture Awards, held on Friday 13 July.[30]

The Digital Harbour Business Association was launched in 2011. This is a group of businesses established in the Digital Harbour precinct in the Docklands. The precinct is a destination for IT, Media and other related businesses. The aim of the association is to promote the businesses within Digital Harbour to the wider Docklands Community and the Melbourne CBD.

Victoria Harbour

[edit]

The Victoria Harbour Precinct is the centrepiece of Docklands. The precinct includes Central Pier and the land south towards the Yarra along with an extension of Collins Street and Bourke Street to meet at the water's edge. It has an area of 280,000 square metres, with 3.7 kilometres of waterfront. The 12-year construction plans for Victoria Harbour include residential apartments, commercial office space, retail space, community facilities and the development of public spaces such as Grand Plaza, Docklands Park and Central Pier.

One of the first completed office buildings in the precinct was the colourful National Australia Bank (NAB) headquarters, located at 800 Bourke Street, which accommodates approximately 3,600 staff. The building has large open floor plates, an atria, a campus-style workplace and a four-star energy rating.

Almost 1,000 Ericsson employees also call Victoria Harbour home, with the company's new Melbourne offices at 818 Bourke Street. Ericsson House sits on the water's edge next door to the National Australia Bank HQ and Dock 5 apartments

The first residential tower to be built at Victoria Harbour was Dock 5. Rising 30 storeys, it was designed by Melbourne firm John Wardle Architects and Hassell. Dock 5 derives its name from its location, which was known as Dock 5.

The Gauge, at 825 Bourke Street was built to house offices for developer Lendlease and Fujitsu. The eight-storey building was designed to achieve a six-star energy rating, becoming the second building in Docklands to do so.

A Safeway supermarket opened in Merchant Street (opposite The Gauge) in 2008, along with a number of other retail tenancies at street level, including Australia Post, a childcare centre, and offices above, which have been occupied by LUCRF Super and the National Union of Workers since 2008.

In 2009 the ANZ Bnak's new world headquarters at 833 Collins Street have was completed. The office complex includes shops, car parking facilities and a YMCA. It enables 6,500 ANZ staff to work in one integrated area. The new ANZ headquarters, designed by Hassell and developed by Lendlease, was expected to become the largest office complex in Australia. Construction commenced in late 2006. It has been designed to achieve a six-star energy rating.

In 2007, Myer announced that it had chosen Victoria Harbour as the location for its new Corporate Store Support Offices. The new offices were built at 800 Collins Street, opposite ANZ.[31]

NewQuay

[edit]

NewQuay, opened in 2002, was one of the first residential and commercial developments in Docklands. It is a mixed-use precinct comprising a number of private residential, hotel accommodation, serviced apartment and retail/commercial properties, developed by the MAB Corporation. The flagship building, Palladio - which is shaped like the prow of a ship - is named after Italian architect Andrea Palladio. The podium building, Sant'Elia is named after another Italian architect, Antonio Sant'Elia. Other buildings are named after Australian artists: Nolan (Sidney Nolan), Arkley (Howard Arkley), Boyd (Arthur Boyd), and Conder (Charles Conder). In 2013, the construction of the twin residential towers "The Quays" was completed.

Aquavista, completed in May 2007, is a strata office development and the first commercial building to be completed in NewQuay, as part of the HQ NewQuay development. Another, the seven-storey 370 Docklands Drive, is currently under construction, with a further two buildings - Lots 5 & 9 - currently under design development.[32]

On 17 October 2007, MAB Corporation launched 'The Avenues at NewQuay' development, consisting of three-storey townhouse residences, with park and waterfront frontages, to be built as part of NewQuay's western precinct. The development is being designed by Plus Architecture.[33][34]

The ground level podiums contain a commercial precinct with a variety of restaurants and cafes including Italian, Indian, Middle Eastern, Cantonese, Moroccan, Cambodian and Modern Australian cuisines.

| Name | Address | Use | Developer | Architect | Height (m) | Storeys | Construction completed | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arkley | 20 Rakaia Way | Residential | MAB Corporation | Plus Architecture | 21 | 2002 | 176 apartments. Named after artist Howard Arkley | |

| Palladio | 15 Caravel Lane | Residential | MAB Corporation | Plus Architecture | Named after Italian architect Andrea Palladio | |||

| Sant'Elia | 30 Newquay Promenade | Residential | MAB Corporation | Plus Architecture | Named after another Italian architect, Antonio Sant'Elia | |||

| Aqua Vista | 401 Docklands Drive | Commercial | MAB Corporation | Plus Architecture | 2007 | |||

| Boyd | 5 Caravel Lane | Residential | MAB Corporation | Plus Architecture | Named after Australian painter Arthur Boyd | |||

| Conder | 2 Newquay Promenade | Residential | MAB Corporation | Fender Katsalidis | Named after Australian artist Charles Conder | |||

| The Quays | 241 Harbour Esplanade | Residential | MAB Corporation | McBride Charles Ryan | 2013 |

Yarra's Edge

[edit]

Yarra's Edge is a residential precinct being developed by Mirvac, and the only Docklands precinct south of the Yarra River. When complete, it will consist of 11 apartment towers, costing A$1.3 billion, and cover 0.15 km2.

A mix of restaurants, cafes and retail, including a day spa and a convenience store. Yarra's Edge also has a 175-berth marina, giving boat owners previously unavailable proximity to Crown Casino and the city.

Yarra's Edge was one of the first developments in Docklands, with construction of Tower 1 commencing in 2000. It is divided into 3 smaller precincts:

- Marina Precinct - Comprising the marina and boardwalk, with 5 tall residential towers ranging in height from 25 to 47 storeys:

- Park Precinct - Comprising Point Park and two residential towers

- River Precinct - Comprising a mix of lower-level, less intense terrace-style developments and three high-rise towers towards the Bolte Bridge

| Name | Address | Use | Developer | Architect | Height (m) | Storeys | Construction completed | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yarra's Edge 1 | 50 Lorimer Street | Residential | Mirvac | Mirvac, Ashton Raggatt McDougall, HPA Architects | 96 | 32 | 2002 | Features a large circular blue glass section in its balustrading. Features RekDek in podium with gymnasium and 25-metre lap pool |

| Yarra's Edge 2 | 60 Lorimer Street | Residential | Mirvac | 70 | 21 | 2003 | Lego block-like with rectangular primary coloured balustrade and rooftop panels. | |

| Yarra's Edge 3 | 70 Lorimer Street | Residential | Mirvac | 104 | 31 | 2003 | Oval footprint with large curved balconies and 4 storey podium | |

| Yarra's Edge 4 | 80 Lorimer Street | Residential | Mirvac | Ashton Raggatt McDougall | 96 | 30 | 2003 | Curved white tower with wide curved balconies and 4 storey podium |

| Yarra's Edge 5 | 90 Lorimer Street | Residential | Mirvac | Wood Marsh | 134 | 41 | 2005 | Angular gold curtain wall glass with angular hat style roof and prominent balcony columns |

| Array (Yarra's Edge 6) | 92-100 Lorimer Street | Residential | Mirvac | 125 | 40 | 2015 | Blue curtain wall glass punctuated by balconies with 5 storey podium | |

| Trielle (Yarra's Edge 9) | 130 Lorimer Street | Residential | Mirvac | Mirvac Design | 135 | 45 | Under construction | Curtain wall glass punctuated by balconies with 5 storey podium |

Webb Bridge

[edit]

Webb Bridge is a bridge designed by Denton Corker Marshall, in collaboration with artist Robert Owen, forming a cycling and pedestrian link to the main part of Docklands, through Docklands Park. It is the conversion of the former Webb Bridge rail link.

Charles Grimes Bridge and Jim Stynes Bridge

[edit]

Charles Grimes Bridge is a dual-carriageway bridge that carries the Docklands Highway over the Yarra River. It was named after New South Wales surveyor general Charles Grimes, who was the first European to sight the Yarra. The bridge, built in 1975 and given its current name in 1983, predates the Docklands development but was connected the new Wurundjeri Way in 1999 to the West Gate Freeway.

The Jim Stynes Bridge was opened in 2014 to carry pedestrian and cyclist traffic underneath the Charles Grimes Bridge from Yarra's Edge to Northbank area.[35]

Greenline

[edit]The Greenline is a shared bicycle and pedestrian path that runs along the Northbank of the Yarra River connecting Yarra's Edge to the Melbourne CBD and North Wharf Victoria Harbour, Docklands Esplanade and the Capital City Trail via the Web Bridge interchange.

Waterfront City

[edit]

Waterfront City is a shopping and entertainment area that includes The District Docklands shopping mall, Melbourne Star Observation wheel, Icehouse ice sports and entertainment centre, and numerous shops and cafes which are centred on this area.

The precinct features an integration of retail, waterfront entertainment, tourism, dining, commercial and urban community. It has an area of 193,000 square metres.

Stage One was completed in December 2005, in time for the Melbourne stopover of the Volvo Ocean Race in January – February 2006 and the Commonwealth Games in March 2006. The precinct originally featured a large circus tent, which hosted the International Circus Spectacular, as well as a mosaic of local entertainers and a number of bronze statues, including Kylie Minogue, John Farnham, Graham Kennedy, Nellie Melba and Dame Edna Everage and a Melbourne Walk of Fame.

Stage Two includes a public entertainment area incorporating the Melbourne Star (previously Southern Star), a 120-metre (390 ft) tall Ferris wheel in the shape of a seven-pointed star, and The District Docklands Shopping Mall. Waterfront city is home to Australia's first Costco Warehouse Store.

In May 2017 Lord Mayor Robert Doyle and Planning Minister Richard Wynne visited The District Docklands to announce a $150 million redevelopment of the centre including an eight-screen Hoyts cinema, which opened in 2018, and a full-line Woolworths supermarket due mid-2019.[37]

During 2017–2018, a collaboration between The District Docklands and Renew Australia allowed the creation of an initiative called the Docklands Art Collective, which made a wing of The District Docklands complex available at very low rents to arts businesses and galleries.[38] These included a photography studio, a puppetry workshop, a comics retailer and printery, a recycled art paper maker and the relocated Blender Studios.[39]

Docklands Studios

[edit]

When it opened in 2004, Central City Studios became Melbourne's largest film and television studio complex. The site is located approximately 2 km north west of the Central Business District. It has an area of 60,000 square metres and currently consists of five film and television sound stages.

The first major contract for the new studios was the American film Ghost Rider in 2005; with a budget of nearly $120 million, at the time it was the biggest feature film to be made in Victoria and features scenes involving Melbourne landmarks. Since then the studios have housed many international productions.

In 2009 the Government of Victoria, together with the Studios, undertook the Future Directions project. This resulted in the State Government committing the Studios to focus on both the international and domestic film and television industries. Further developments to the infrastructure of the site are planned, including a sixth sound stage.

On 11 October 2010 the studios were re-branded as Docklands Studios Melbourne, formally adopting the name by which the studios were commonly known.

Heritage

[edit]Significant heritage buildings include the No 2 Goods Shed (now a mixed use development),[40] former railway offices at 67 Spencer Street (now the Grand Hotel), The Mission to Seafarers building,[41] Victoria Dock and Central Pier,[42] Queens Warehouse (adaptively reused as a vintage car museum),[43] Docklands Park gantry crane and a small number of warehouses and container sheds.

- Victoria Dock and Central Pier (1887-1892)[44]

- No.2 Goods Shed (1889-1890)[45]

- Queen's Warehouse (1890)[46]

- Batman's Hill Retaining Wall (1890)[47]

- Former Victorian Railways Headquarters (1893)[48]

- Mission to Seamen (1919)[49]

- Berth No. 5. North Wharf (1948)[50]

- History of Transport Mural (1973), DFO[51]

-

67 Spencer Street, one of Melbourne's largest 19th century office buildings, now the Grand Hotel

-

No 2 Goods Shed, Australia's longest building once completed in 1889, now a mixed use development

-

Queen's Warehouse houses the Fox Classic Cars collection

-

Mission to Seamen is preserved as a museum

Transport

[edit]

Docklands has access to road, rail and water transports.

Docklands Highway or Wurundjeri Way is the main road through Docklands. It connects to the nearby Westgate Freeway on the southern end and links to the CBD including extensions from Flinders Street, Collins Street and La Trobe Street.

Southern Cross station, near the eastern edge of Docklands, is the closest passenger railway station. It is also the major interchange for metropolitan and intercity rail. Much of Docklands area remains covered by rail yards previously used for freight transport and rolling stock which are being progressively reclaimed or built over.

Trams in Docklands include the free City Circle tram, along Docklands Drive and to and from Waterfront City. As Docklands has developed, tram routes have been extended and rerouted into the area. Route 70 also runs to Waterfront City. Route 75 runs along Harbour Esplanade, terminating at Footscray Road. Routes 11 and 48 run along Collins Street to Victoria Harbour. Route 30 enters Docklands via La Trobe Street, terminating at the north end of Harbour Esplanade. Route 86 runs along La Trobe Street and Docklands Drive, terminating at Waterfront City.

Docklands also includes major pedestrian links with a concourse extending from Bourke Street and extensive promenades along the waterfront, including the wide Harbour Esplanade.

Several offroad bicycle paths run through Docklands, all of which connect through the central spine of Webb Bridge, Docklands Park and Harbour Esplanade, connecting Melbourne City Centre to the inner western suburbs and the Capital City Trail.

There are also three ferry terminals which connect Docklands to the Melbourne City Centre and inner bayside suburbs. One at Victoria Harbour, one at NewQuay and one at Yarra's Edge.

Sports and recreation

[edit]

- The Docklands Stadium (currently known as Marvel Stadium), located just northwest of the Southern Cross railway station, is the home ground to five AFL football clubs (St Kilda, North Melbourne, Carlton, Essendon and Western Bulldogs) and one Big Bash League cricket team (Melbourne Renegades). It was also one of the venues for the 2003 Rugby World Cup and the 2006 Commonwealth Games, and hosted the 2015 Speedway Grand Prix of Australia.

- The O'Brien Icehouse, located between the Moonee Ponds Creek (accessible via the creek trail) and the Melbourne Star observation wheel, is the largest ice sports venue and the only dual-rink facility in Australia. It is the home to both of the two Victorian AIHL ice hockey teams, the Melbourne Ice and Melbourne Mustangs.

- The Docklands Sports Courts is a public urban park on Harbour Esplanade featuring two mixed-use court for basketball, netball, soccer/futsal and dodgeball and an outdoor ping-pong table, as well as children's play parks and shading parasols. The Docklands Park is across the Esplanade, offering more green spaces with bicycle trails.

- Lasersports Australia operates a booking-based laser clay shooting business at New Quay.

Demographics and industry

[edit]In the 2016 Census, there were 10,964 people in Docklands. 27.3% of people were born in Australia. The most common countries of birth were China 16.5%, India 12.7%, South Korea 3.1%, Malaysia 2.6% and England 2.3%. 34.4% of people only spoke English at home. Other languages spoken at home included Mandarin 18.3%, Hindi 4.9%, Cantonese 3.1%, Korean 2.9% and Telugu 2.4%. The most common response for religion in Docklands (State Suburbs) was No Religion at 38.1%.

Of the occupied private dwellings in Docklands, 97.1% were flats or apartments and 2.3% were semi-detached, row or terrace houses, townhouses, etc.[52]

In 2009, there were just under 10,000[53] working mostly in office and retail industries.

In the 2021 Census, the Docklands had grown to a population of 15,495 people. [54]

Local media

[edit]The precinct has two publications, Docklands News and 3008 Docklands Magazine.

The Docklands Community News' first edition was published in 2003, and both DCN & 3008 Docklands Magazine have grown with the Docklands precincts' population. Both publications are printed and distributed to all businesses and residences within Docklands, which allows for a regular readership of over 10,000. The DCN paper informs the community of relevant news relating to Docklands as well as supplying residents, business owners and workers with a platform for community discussion.

3008 Docklands Magazine also covers all matters relating to the Docklands community and businesses, but also covers events and news pertaining to Melbourne City and the surrounding suburbs, as Docklands is under the jurisdiction of the City of Melbourne. 3008 Docklands Magazine is a glossy, well-produced, stylish publication which is both informative and interesting and has been well received by its reader base since its first issue back in May 2006. 3008 Docklands Magazine has a significant online following.

Response and reception

[edit]

The planning of Docklands has raised a large amount of public debate and the area has created significant controversy, particularly the failed Ferris wheel.[55]

In 1999, Melbourne City Council Director of Projects criticised the disconnection of the precinct to the CBD, claiming that the lack of transport links, particularly pedestrian, meant Docklands was "seriously flawed".[56]

The problem was exacerbated in 2005, when the pedestrian link between Lonsdale Street and Docklands proposed in 2001[57] was cut from the final design of the Southern Cross Station development due to budget blowouts.

In 2006, Royce Millar of The Age referred to it as a "wasted opportunity".[6]

In 2008, the City of Melbourne released a report which criticised Docklands' lack of transport and wind tunnel effect, lack of green spaces and community facilities.[58][59]

In 2009, Neil Mitchell wrote for The Age declaring Docklands as a planning "dud".[7] The Lord Mayor, Robert Doyle, has been openly critical of Docklands, claiming in 2009 that it lacks any form of "social glue".[8]

However, despite the local criticism, in 2009, Sydney travel writer Mal Chenu described Melbourne Docklands as "the envy of Sydneysiders".[60]

In 2010, VicUrban's general manager David Young acknowledged that Harbour Esplanade "doesn't stack up".[61] Kim Dovey, professor of architecture and design at the University of Melbourne, added that Harbour Esplanade was "too big" and claimed that Docklands was "so badly done" that it required a "major rethink".[61]

The Docklands area came under heavy criticism for the failure to provide a school with families being forced out of the area or needing to commute to state schools already under pressure from the critical shortage of schools in the inner suburbs.[62][63][64] A private school, Melbourne City School, opened on King Street in 2010 but closed in 2012 due to low enrollments.[65] Docklands Primary School in NewQuay opened in January 2021. The Docklands Sports Club has run Junior Football and Cricket programs since Summer 2019.

George Savvides, CEO of Medibank, which has been based in Docklands since 2004, has been critical of the area's lack of soul and amenity,[66] but the company has nevertheless chosen to remain committed to the area.[67][68]

"Ghost town" reputation and post COVID-19 Pandemic decline

[edit]

In the late 2010s, the area developed a reputation as a ghost town due to rapidly declining activity. In 2022 the Victorian Liberal Party declared it as such, citing neglect and poor planning by successive governments causing an extreme lack of activity, especially due to the permanent closure of Central Pier in 2019.[69] Docklands has consistently been labelled this way by the media post COVID-19 pandemic. By 2023 among the stark lack of activity was exacerbated by a trend of owner occupiers converting their residences to Airbnbs, Costco shutting its flagship store, several prominent businesses closing their doors, and the Walk of Stars being permanently relocated elsewhere.[70][71][72]

Public art

[edit]There are approximately 68 pieces of public art in the Docklands Precincts,[73] with works from Australian and New Zealand artists. There are self-guided tours and maps available for the public to discover the artworks.[74]

-

"Cow up a tree" by John Kelly. Harbour Esplanade

-

"Bunjil" by Bruce Armstrong. Wurundjeri Way

-

"Aurora" by Geoffrey Bartlett on the corner of Harbour Esplanade and Collins Street

-

"Toy Rabbit" by Emily Floyd

-

"Shoal Fly By" by Cat McLeod and Michael Bellemo. Harbour Esplanade

-

"Unfurling" by Andrew Rogers. Harbour Esplanade

-

"Threaded Field" by Simon Perry. Harbour Esplanade

-

"Continuum" by Michael Snape. Harbour Esplanade

-

"Aqualung" by John Mead at Captain Walk

-

"Blowhole" by Duncan Stemler

-

"Lillies" by Adrian Mauriks at New Quay

-

"Panoramio" by Russell Anderson

-

"Reed Vessel" by Virginia King

-

"Unfurling Curve" by Andrew Rogers

-

"Wulunj" by Glenn Romanis and Brodie Hill

-

"Bicycle-End". Harbour Esplanade

Notable residents

[edit]- Sally Capp – 104th Lord Mayor of Melbourne (Victoria Harbour)[75]

- Sam Newman – former AFL player and sportscaster (Yarra's Edge)[76][77]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Docklands (Suburbs and Localities)". 2021 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ a b Tomazin, Farrah; Donovan, Patrick; Mundell, Meg (7 December 2002). "Dance trance". The Age. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017.

- ^ CBRE report pointing to Melbourne Docklands outperforming all other Australian office markets Archived 20 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Draper, Michelle (28 September 2006). "ANZ deal sparks Docklands concern". The Age. Fairfax. Archived from the original on 14 March 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ Johnston, Matt (3 September 2009). "Docklands to get more parkland, 1000 more homes in $1b project". Herald Sun. News Limited. Archived from the original on 5 September 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ a b Millar, Royce (17 June 2006). "Docklands a wasted opportunity?". The Age. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 29 September 2008.

- ^ a b "dead link". Herald Sun. News Limited. Archived from the original on 28 March 2009.

- ^ a b Dowling, Jason; Lahey, Kate (16 March 2009). "Doyle call for council to take on Docklands". The Age. Fairfax. Archived from the original on 29 May 2009.

- ^ Keble, R. A.; Macpherson, J. H. (1946). "The contemporaneity of the river terraces of the Maribyrnong River, Victoria, with those of the Upper Pleistocene in Europe". Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria. 14 (2): 52–68. doi:10.24199/j.mmv.1946.14.05. ISSN 0083-5986.

- ^ a b "THE RECLAMATION OF THE WEST MELBOURNE SWAMP". The Argus (Melbourne). No. 9, 890. Victoria, Australia. 26 February 1878. p. 6. Retrieved 16 May 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "PHILOSOPHICAL INSTITUTE OF VICTORIA". The Argus (Melbourne). No. 3713. Victoria, Australia. 6 May 1858. p. 7. Retrieved 16 May 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Cox, H. L. (Henry L., Bourchier, T., & McHugh, P. H. (1866). Victoria-Australia, Port Phillip. Hobson Bay and River Yarra leading to Melbourne [cartographic material] / surveyed by H.L. Cox ; assisted by Thos. Bourchier & P.H. McHugh, 1864 ; engraved by J. & C. Walker. London: Published by the Admiralty.

- ^ Victorian Railways. Way and Works Branch; Ballard, Edw (1924), V. R. locality plan of West Melbourne swamp (Amended 25.1.24 ed.), Victorian Railways, retrieved 16 May 2024

- ^ Oswald Barnett (2 June 2011), 1930s. West Melbourne swamp made from rubbish tip, Melbourne Library Service, retrieved 16 May 2024

- ^ AA - Melbourne Docklands - September/October 1998 Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g Dovey, Kim (2005). Fluid City: Transforming Melbourne's Waterfront. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

- ^ Docklands Public Realm Plan - City of Melbourne 2012

- ^ Mirvac's Transformative Project on Melbourne's Northbank is Approved 2 February 2021

- ^ The Emergence of Melbourne's Northbank Precinct Domain.com.au

- ^ Craig, Natalie (13 December 2007). "New Age building revealed". The Age. Fairfax. Archived from the original on 16 December 2007.

- ^ Millar, Royce (2 August 2007). "Visionary architect set to transform Docklands". The Age. Fairfax. Archived from the original on 7 February 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ Victoria, Development (29 March 2017). "Home". www.docklands.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Victoria, Development (29 March 2017). "Home". www.docklands.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Harbour Esplanade redevelopment from Docklands News 3 June 2010

- ^ https://participate.melbourne.vic.gov.au/harbour-esplanade Harbour Esplanade - Participate Melbourne Community Consultation 2014

- ^ Central Pier Project 2024

- ^ Demolition of Central Pier progresses by Sean Car 31 January 2024

- ^ Rebuild pier pressure grows as report shows shutdown will cost $865m by Noel Towell for The Age 17 December 2021

- ^ Kicking Goals On Docklands Waterfront Premier of Victoria 10 January 2024

- ^ Digital Harbour – latest news Archived 1 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Victoria, Development (29 March 2017). "Home". www.docklands.com.au. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ HQ NewQuay: Lots 5 & 9 Archived 14 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NewQuay Docklands - "The Avenues at NewQuay" Melbourne's Multi-Million Dollar Waterside Housing Precinct: Melbourne's inner-city waterfront precinct Archived 30 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Marina Avenue & Parkside Avenue Archived 28 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Masanauskas, John; Toy, Mitchell (20 December 2012). "Works begin on city bridge to honour Jim Stynes in Northbank precinct". Herald Sun.

- ^ Kylie Minogue and friends evicted from Docklands to make way for new tower By Larissa Ham. The Age. 29 April 2016

- ^ Liu, Sunny. "New reasons to visit Harbour Town". Docklands News. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ "The Docklands Art Collective – Rent-Free Space For Creatives!". Renew Australia. 19 June 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ "Docklands Art Collective". Renew Australia. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ Equiset.com.au Archived 2 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Melbourneopenhouse.org Archived 16 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Melbourneopenhouse.org Archived 17 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Fox Classic Car Museum". www.foxcollection.org.au. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Victoria Dock - Victorian Heritage Register

- ^ No.2 Goods Shed - Victorian Heritage Register

- ^ Queen's Warehouse - Victorian Heritage Register

- ^ Retaining Wall - Victorian Heritage Register

- ^ Former Victorian Railways Headquarters - Victorian Heritage Register

- ^ Mission to Seamen - Victorian Heritage Register

- ^ Berth No. 5. North Wharf - Victorian Heritage Register

- ^ History of Transport Mural - Victorian Heritage Register

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Docklands (State Suburb)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ Victoria, Development (29 March 2017). "Home" (PDF). www.docklands.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ "2021 Docklands, Census All persons QuickStats | Australian Bureau of Statistics".

- ^ "PM - Melbourne's 'big wheel' already drawing criticism". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 12 May 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ "The World Today Archive - Docklands looks to the future". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ DPC.vic.gov.au Archived 19 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lucas, Clay (2 January 2008). "Vision for 'friendlier' Docklands". The Age. Fairfax. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ Melbourne.vic.gov.au Archived 15 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chenu, Mal (6 August 2009). "Cows, cranes and goalposts". Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ a b Cooke, Dewi (17 March 2010). "Docklands $9bn plan for next decade". The Age. Fairfax. Archived from the original on 4 February 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ Kinkade, Alison (30 April 2010). ""We are not happy" - Docklands families want a school". Docklands News. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012.

- ^ Craig, Natalie (13 June 2010). "Critical shortages in inner-city schools as population swells". The Age. Archived from the original on 13 December 2011.

- ^ Price, Nic (16 April 2012). "Primary school ambition at Docklands". Nurture.[dead link]

- ^ Price, Nic (11 February 2013). "Residents in inner Melbourne's newest suburbs, the Docklands and Southbank, renew calls for a new school".

- ^ Dowling, Jason (27 September 2011). "Lack of 'soul' has Docklands tenant ready to leave". The Age. Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Scanlan, Shane. "Medibank to stay in Docklands - Docklands News". www.docklandsnews.com.au. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Dowling, Jason (3 July 2012). "Docklands critic has designs on a new cityscape". The Age. Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ DOCKLANDS PRECINCT A GHOST TOWN UNDER LABOR by Liberal Party 17 May 2022

- ^ ‘It's depressing’: Fed-up business owner exposes sad state of Melbourne's CBD by Rebecca Borg for News.com.au 12 July 2023

- ^ Docklands can shake its ‘ghost-town’ reputation. Here's how by Najma Sambul for The Age 27 January 2024

- ^ Docklands: How to fix Melbourne's most maligned suburb from The Age 12 April 2024

- ^ "Docklands - Development Victoria". 30 October 2019.

- ^ "Docklands Public Art Walk (Central Melbourne) - Art -".

- ^ Lord Mayor Sally Capp switches Docklands for Carlton Katie Johnson Docklands News 2 September 2021

- ^ "Sam Newman gives skateboarders a tongue lashing".

- ^ Docklands: Sam Newman's former New York-style penthouse listing spruiked by Kevin Sheedy Alesha Capone RealEstate.com.au 19 April 2024

Further reading

[edit]- Kim Dovey: Fluid City: Transforming Melbourne's Urban Waterfront, London: Routledge, 2005

External links

[edit]- Official website

- 3008 Docklands Magazine Website

- Docklands Community News

- NewQuay website

- Waterfront City website Archived 17 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Victoria Harbour website

- Yarra's Edge website

- Digital Harbour website

- Victoria Online - Docklands Authority

- Australian Places - Docklands

- How public is your private? Article about Docklands by Martin Musiatowicz