The Walt Disney Company

The Walt Disney Studios, the company's headquarters in Burbank, California, 2016 | |

| Formerly |

|

|---|---|

| Company type | Public |

| ISIN | US2546871060 |

| Industry | |

| Predecessor | Laugh-O-Gram Studio |

| Founded | October 16, 1923 |

| Founders | |

| Headquarters | The Walt Disney Studios, , United States |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 225,000 (FY23) |

| Divisions | |

| Subsidiaries | National Geographic Partners (73%) |

| Website | thewaltdisneycompany |

| Footnotes / references Financials as of fiscal year ended September 30, 2023[update]. References:[1][2][3] | |

The Walt Disney Company, commonly referred to as simply Disney, is an American multinational mass media and entertainment conglomerate headquartered at the Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California. Disney was founded on October 16, 1923, by brothers Walt Disney and Roy Oliver Disney as Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio; it also operated under the names Walt Disney Studio and Walt Disney Productions before changing it to its current name in 1986. In 1928, Disney established itself as a leader in the animation industry with the short film Steamboat Willie. The film used synchronized sound to become the first post-produced sound cartoon, and popularized Mickey Mouse,[4] who became Disney's mascot and corporate icon.[not verified in body]

After becoming a major success by the early 1940s, Disney diversified into live-action films, television, and theme parks in the 1950s. However, following Walt Disney's death in 1966, the company's profits, especially in the animation division, began to decline. In 1984, Disney's shareholders voted Michael Eisner as CEO, who led a reversal of the company's decline through a combination of international theme park expansion and the highly successful Disney Renaissance period of animation in the 1990s. In 2005, under new CEO Bob Iger, the company continued to expand into a major entertainment conglomerate with the acquisitions of Pixar, Marvel Entertainment, Lucasfilm, and 21st Century Fox. In 2020, Bob Chapek became the head of Disney after Iger's retirement. However, Chapek was ousted in 2022 and Iger was reinstated as CEO.[5]

The company is known for its film studio division, the Walt Disney Studios, which includes Walt Disney Pictures, Walt Disney Animation Studios, Pixar, Marvel Studios, Lucasfilm, 20th Century Studios, 20th Century Animation, and Searchlight Pictures. Disney's other main business units include divisions in television, broadcasting, streaming media, theme park resorts, consumer products, publishing, and international operations. Through these divisions, Disney owns and operates the ABC television network; cable television networks such as Disney Channel, ESPN, Freeform, FX, and National Geographic; publishing, merchandising, music, and theater divisions; direct-to-consumer streaming services such as Disney+, ESPN+, Hulu, and Hotstar; and Disney Experiences, which includes several theme parks, resort hotels, and cruise lines around the world.

Disney is one of the biggest and best-known companies in the world and was ranked number 48 on the 2023 Fortune 500 list of biggest companies in the United States by revenue.[6] In 2023, the company's seat in Forbes Global 2000 was 87.[7] Since its founding, the company has won 135 Academy Awards, 26 of which were awarded to Walt. The company has been said to have produced some of the greatest films of all time, as well as revolutionizing the theme park industry. The company, which has been public since 1940, trades on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) with ticker symbol DIS and has been a component of the Dow Jones Industrial Average since 1991. In August 2020, about two-thirds of the stock was owned by large financial institutions. The company celebrated their 100th anniversary on October 16, 2023.

History

1923–1934: Founding, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, Mickey Mouse, and Silly Symphonies

In 1921, American animators Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks founded Laugh-O-Gram Studio in Kansas City, Missouri.[8] Iwerks and Disney went on to create short films at the studio. The final one, in 1923, was entitled Alice's Wonderland and depicted child actress Virginia Davis interacting with animated characters. While Laugh-O-Gram's shorts were popular in Kansas City, the studio went bankrupt in 1923 and Disney moved to Los Angeles, to join his brother Roy O. Disney, who was recovering from tuberculosis.[9] Shortly after Walt's move, New York film distributor Margaret J. Winkler purchased Alice's Wonderland, which began to gain popularity. Disney signed a contract with Winkler for $1,500, to create six series of Alice Comedies, with an option for two more six-episode series.[10][11] Walt and Roy Disney founded Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio on October 16, 1923, to produce the films.[12] In January 1926, the Disneys moved into a new studio on Hyperion Street and the studio's name was changed to Walt Disney Studio.[13]

After producing Alice films over the next 4 years, Winkler handed the role of distributing the studio's shorts to her husband, Charles Mintz. In 1927, Mintz asked for a new series, and Disney created his first series of fully animated shorts, starring a character named Oswald the Lucky Rabbit.[14] The series was produced by Winkler Pictures and distributed by Universal Pictures. The Walt Disney Studios completed 26 Oswald shorts.[15]

In 1928, Disney and Mintz entered into a contract dispute, with Disney asking for a larger fee, while Mintz sought to reduce the price. Disney discovered Universal Pictures owned the intellectual property rights to Oswald, and Mintz threatened to produce the shorts without him if he did not accept the reduction in payment.[15][16] Disney declined and Mintz signed 4 of Walt Disney Studio's primary animators to start his own studio; Iwerks was the only top animator to remain with the Disney brothers.[17] Disney and Iwerks replaced Oswald with a mouse character originally named Mortimer Mouse, before Disney's wife urged him to change the name to Mickey Mouse.[18][19] In May 1928, Mickey Mouse debuted in test screenings of the shorts Plane Crazy and The Gallopin' Gaucho. Later that year, the studio produced Steamboat Willie, its first sound film and third short in the Mickey Mouse series, which was made using synchronized sound, becoming the first post-produced sound cartoon.[4] The sound was created using Powers' Cinephone system, which used Lee de Forest's Phonofilm system.[20] Pat Powers' company distributed Steamboat Willie, which was an immediate hit.[18][21][22] In 1929, the company successfully re-released the two earlier films with synchronized sound.[23][24]

After the release of Steamboat Willie at the Colony Theater in New York, Mickey Mouse became an immensely popular character.[24][18] Disney Brothers Studio made several cartoons featuring Mickey and other characters.[25] In August 1929, the company began making the Silly Symphony series with Columbia Pictures as the distributor, because the Disney brothers felt they were not receiving their share of profits from Powers.[22] Powers ended his contract with Iwerks, who later started his own studio.[26] Carl W. Stalling played an important role in starting the series, and composed the music for early films but left the company after Iwerks' departure.[27][28] In September, theater manager Harry Woodin requested permission to start a Mickey Mouse Club at his theater the Fox Dome to boost attendance. Disney agreed, but David E. Dow started the first-such club at Elsinore Theatre before Woodin could start his. On December 21, the first meeting at Elsinore Theatre was attended by around 1,200 children.[29][30] On July 24, 1930, Joseph Conley, president of King Features Syndicate, wrote to the Disney studio and asked the company to produce a Mickey Mouse comic strip; production started in November and samples were sent to King Features.[31] On December 16, 1930, the Walt Disney Studios partnership was reorganized as a corporation with the name Walt Disney Productions, Limited, which had a merchandising division named Walt Disney Enterprises, and subsidiaries called Disney Film Recording Company, Limited and Liled Realty and Investment Company; the latter of which managed real estate holdings. Walt Disney and his wife held 60% (6,000 shares) of the company, and Roy Disney owned 40%.[32]

The comic strip Mickey Mouse debuted on January 13, 1930, in New York Daily Mirror and by 1931, the strip was published in 60 newspapers in the US, and in 20 other countries.[33] After realizing releasing merchandise based on the characters would generate more revenue, a man in New York offered Disney $300 for license to put Mickey Mouse on writing tablets he was manufacturing. Disney accepted and Mickey Mouse became the first licensed character.[34][35] In 1933, Disney asked Kay Kamen, the owner of a Kansas City advertising firm, to run Disney's merchandising; Kamen agreed and transformed Disney's merchandising. Within a year, Kamen had 40 licenses for Mickey Mouse and within two years, had made $35 million worth of sales. In 1934, Disney said he made more money from the merchandising of Mickey Mouse than from the character's films.[36][37]

The Waterbury Clock Company created a Mickey Mouse watch, which became so popular it saved the company from bankruptcy during the Great Depression. During a promotional event at Macy's, 11,000 Mickey Mouse watches sold in one day; and within two years, two-and-a-half million watches were sold.[38][33][37] As Mickey Mouse become a heroic character rather than a mischievous one, Disney needed another character that could produce gags.[39] Disney invited radio presenter Clarence Nash to the animation studio; Disney wanted to use Nash to play Donald Duck, a talking duck that would be the studio's new gag character. Donald Duck made his first appearance in 1934 in The Wise Little Hen. Though he did not become popular as quickly as Mickey had, Donald Duck had a featured role in Donald and Pluto (1936), and was given his own series.[40]

After a disagreement with Columbia Pictures about the Silly Symphony cartoons, Disney signed a distribution contract with United Artists from 1932 to 1937 to distribute them.[41] In 1932, Disney signed an exclusive contract with Technicolor to produce cartoons in color until the end of 1935, beginning with the Silly Symphony short Flowers and Trees (1932).[42] The film was the first full-color cartoon and won the Academy Award for Best Cartoon.[4] In 1933, The Three Little Pigs, another popular Silly Symphony short, was released and also won the Academy Award for Best Cartoon.[25][43] The song from the film "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?", which was composed by Frank Churchill—who wrote other Silly Symphonies songs—became popular and remained so throughout the 1930s, and became one of the best-known Disney songs.[27] Other Silly Symphonies films won the Best Cartoon award from 1931 to 1939, except for 1938, when another Disney film, Ferdinand the Bull, won it.[25]

1934–1949: Golden Age of Animation, strike, and wartime era

In 1934, Walt Disney announced a feature-length animated film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. It would be the first cel animated feature and the first animated feature produced in the US. Its novelty made it a risky venture; Roy tried to persuade Walt not to produce it, arguing it would bankrupt the studio, and while widely anticipated by the public, it was referred to by some critics as "Disney's Folly".[44][45] Walt directed the animators to take a realistic approach, creating scenes as though they were live action.[46][47] While making the film, the company created the multiplane camera, consisting of pieces of glass upon which drawings were placed at different distances to create an illusion of depth in the backgrounds.[48] After United Artists attempted to attain future television rights to the Disney shorts, Walt signed a distribution contract with RKO Radio Pictures on March 2, 1936.[49] Walt Disney Productions exceeded its original budget of $150,000 for Snow White by ten times; its production eventually cost the company $1.5 million.[44]

Snow White took 3 years to make, premiering on December 12, 1937. It was an immediate critical and commercial success, becoming the highest-grossing film up to that point, grossing $8 million (equivalent to $169,555,556 in 2023 dollars); after re-releases, it grossed a total of $998,440,000 in the US adjusted for inflation.[50][51] Using the profits from Snow White, Disney financed the construction of a new 51-acre studio complex in Burbank, which the company fully moved into in 1940 and where the company is still headquartered.[52][53] In April 1940, Disney Productions had its initial public offering, with the common stock remaining with Disney and his family. Disney did not want to go public but the company needed the money.[54]

Shortly before Snow White's release, work began on the company's next features, Pinocchio and Bambi. Pinocchio was released in February 1940 while Bambi was postponed.[49] Despite Pinocchio's critical acclaim (it won the Academy Awards for Best Song and Best Score and was lauded for groundbreaking achievements in animation),[55] the film performed poorly at the box office, due to World War II affecting the international box office.[56][57]

The company's third feature Fantasia (1940) introduced groundbreaking advancements in cinema technology, chiefly Fantasound, an early surround sound system making it the first commercial film to be shown in stereo. However, Fantasia similarly performed poorly at the box office. [58][59][60] In 1941, the company experienced a major setback when 300 of its 800 animators, led by one of the top animators Art Babbitt, went on strike for 5 weeks for unionization and higher pay. Walt Disney publicly accused the strikers of being party to a communist conspiracy, and fired many of them, including some of the studio's best.[61][62] Roy unsuccessfully attempted to persuade the company's main distributors to invest in the studio, which could no longer afford to offset production costs with employee layoffs.[63] The anthology film The Reluctant Dragon (1941), ran $100,000 short of its production cost, contributing to the studio's financial woes.[clarification needed][64]

While negotiations to end the strike were underway, Walt and studio animators embarked on a 12-week goodwill visit to South America, funded by the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs.[65] During the trip, the animators began plotting films, taking inspiration from the local environments and music.[66] As a result of the strike, federal mediators compelled the studio to recognize the Screen Cartoonist's Guild and several animators left, leaving it with 694 employees.[67][62] To recover from their financial losses, Disney rushed into production the studio's 4th animated feature Dumbo (1941) on a cheaper budget, which performed well at the box office, infusing the studio with much needed cash.[55][68] After US entry into World War II, many of the company's animators were drafted into the army.[69] 500 United States Army soldiers occupied the studio for 8 months to protect a nearby Lockheed aircraft plant. While they were there, the soldiers fixed equipment in large soundstages and converted storage sheds into ammunition depots.[70] The United States Navy asked Disney to produce propaganda films to gain support for the war, and with the studio badly in need of profits, Disney agreed, signing a contract for 20 war-related shorts for $90,000.[71] Most of the company's employees worked on the project, which spawned films such as Victory Through Air Power, and others which included some of the company's characters.[72][69]

In August 1942, Disney released its fifth feature film, Bambi, after five years in development, and performed poorly at the box office.[73] Later, as products of the South American trip, Disney released the features Saludos Amigos (1942) and The Three Caballeros (1944).[69][74] This was a new strategy of releasing package films, collections of short cartoons grouped to make feature films. Both performed poorly. Disney released more package films through the rest of the decade, including Make Mine Music (1946), Fun and Fancy Free (1947), Melody Time (1948), and The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949), to try to recover from its financial losses.[69] Disney began producing less-expensive live-action films mixed with animation, beginning with Song of the South (1946) which would become one of Disney's most controversial films.[75][76] As a result of its financial problems, Disney began re-releasing its feature films in 1944.[76][77] In 1948, it began premiering the nature documentary series, True-Life Adventures, which ran until 1960, winning 8 Academy Awards.[78][79] In 1949, the Walt Disney Music Company was founded to help with profits for merchandising.[80]

1950–1967: Live-action films, television, Disneyland, and Walt Disney's death

In the 1950s, Disney returned to producing full-length animated feature films, beginning with Cinderella (1950), its first feature in eight years. A critical and commercial success, Cinderella saved Disney after the financial pitfalls of the wartime era; it was its most financially successful film since Snow White, making $8 million in its first year. Walt began to reduce his involvement with animation, focusing his attention on the studio's increasingly diverse portfolio of projects, including live-action films (of which Treasure Island was the studio's first), television and amusement parks.[81][82] In 1950 the company made its first foray into television when NBC aired "One Hour in Wonderland", a promotional program for Disney's next animated film, Alice in Wonderland (1951), and sponsored by Coca-Cola.[83] Alice was financially unsuccessful, falling $1 million short of the production budget.[84] In February 1953, Disney's next animated film Peter Pan was released to financial success;[85] it was the last Disney film distributed by RKO after Disney ended its contract and created its own distribution company Buena Vista Distribution.[86]

According to Walt, he first had the idea of building an amusement park during a visit to Griffith Park with his daughters. He said he watched them ride a carousel and thought there "should be ... some kind of amusement enterprise built where the parents and the children could have fun together".[87][88] Initially planning the construction of an eight-acre (3.2 ha) Mickey Mouse Park near the Burbank studio, Walt changed the planned amusement park's name to Disneylandia, then to Disneyland.[89] A new company, WED Enterprises (now Walt Disney Imagineering), was formed in 1952 to design and construct the park.[90] Drawing inspiration from amusement parks in the US and Europe, Walt approached the design of Disneyland with an emphasis on thematic storytelling and cleanliness, innovative approaches for amusement parks of the time.[91][92] The plan to build the park in Burbank was abandoned when Walt realized 8 acres would not be enough to accomplish his vision. Disney acquired 160 acres (65 ha) of orange groves in Anaheim, southeast of LA in neighboring Orange County, at $6,200 per acre to build the park.[93] Construction began in July 1954.

To finance the construction of Disneyland, Disney sold his home at Smoke Tree Ranch in Palm Springs and the company promoted it with a television series of the same name aired on ABC.[94] The Disneyland television series, which would be the first in a long-running series of successful anthology television programs for the company, was a success and garnered over 50% of viewers in its time slot, along with praise from critics.[95] In August, Walt formed another company Disneyland, Inc. to finance the park, whose construction costs totaled $17 million.[96]

In October, with the success of Disneyland, ABC allowed Disney to produce The Mickey Mouse Club, a variety show for children; the show included a daily Disney cartoon, a children's newsreel, and a talent show. It was presented by a host, and talented children and adults called "Mousketeers" and "Mooseketeers", respectively.[97] After the first season, over ten million children and five million adults watched it daily; and two million Mickey Mouse ears, which the cast wore, were sold.[98] In December 1954, the five-part miniseries Davy Crockett, premiered as part of Disneyland, starring Fess Parker. According to writer Neal Gabler, "[It] became an overnight national sensation", selling 10 million Crockett coonskin caps.[99] The show's theme song "The Ballad of Davy Crockett" became part of American pop culture, selling 10 million records. Los Angeles Times called it "the greatest merchandising fad the world had ever seen".[100][101] In June 1955, Disney's 15th animated film Lady and the Tramp was released and performed better at the box office than any other Disney films since Snow White.[102]

Disneyland opened on July 17, 1955; it was a major media event, broadcast live on ABC with actors Art Linkletter, Bob Cummings, and Ronald Reagan hosting. It garnered over 90 million viewers, becoming the most-watched live broadcast to that date.[103] While the park's opening day was disastrous (restaurants ran out of food, the Mark Twain Riverboat began to sink, other rides malfunctioned, and the drinking fountains were not working in the 100 °F. (38 °C) heat),[104][96] the park became a success with 161,657 visitors in its first week and 20,000 visitors a day in its first month. After its first year, 3.6 million people had visited, and after its second year, four million more guests came, making it more popular than the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone National Park. That year, the company earned a gross total of $24.5 million compared to the $11 million the previous year.[105]

Disney continued to delegate much of the animation work to the studio's top animators, known as the Nine Old Men. The company produced an average of five films per year throughout the 1950s and 60s.[106] Animated features of this period included Sleeping Beauty (1959), One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961), and The Sword in the Stone (1963).[107] Sleeping Beauty was a financial loss for the company, and at $6 million, had the highest production costs up to that point.[108] One Hundred and One Dalmatians introduced an animation technique using the xerography process to electromagnetically transfer the drawings to animation cels, resulting in a transformed art style for the studio's animated films.[109] In 1956, the Sherman Brothers, Robert and Richard, were asked to produce a theme song for the television series Zorro.[110] The company hired them as exclusive staff songwriters, an arrangement that lasted 10 years. They wrote many songs for Disney's films and theme parks, and several were commercial hits.[111][112] In the late 1950s, Disney ventured into comedy with the live-action films The Shaggy Dog (1959), which became the highest-grossing film in the US and Canada for Disney at over $9 million,[113] and The Absent Minded Professor (1961), both starring Fred MacMurray.[107][114]

Disney also made live-action films based on children's books including Pollyanna (1960) and Swiss Family Robinson (1960). Child actor Hayley Mills starred in Pollyanna, for which she won an Academy Juvenile Award. Mills starred in 5 other Disney films, including a dual role as the twins in The Parent Trap (1961).[115][116] Another child actor, Kevin Corcoran, was prominent in many Disney live-action films, first appearing in a serial for The Mickey Mouse Club, where he would play a boy named Moochie. He worked alongside Mills in Pollyanna, and starred in features such as Old Yeller (1957), Toby Tyler (1960), and Swiss Family Robinson.[117] In 1964, the live action/animation musical film Mary Poppins was released to major commercial success and rapturous critical acclaim, becoming the year's highest-grossing film and winning five Academy Awards, including Best Actress for Julie Andrews as Poppins and Best Song for the Sherman Brothers, who also won Best Score for the film's "Chim Chim Cher-ee".[118][119]

Throughout the 1960s, Dean Jones, whom The Guardian called "the figure who most represented Walt Disney Productions in the 1960s", starred in 10 Disney films, including That Darn Cat! (1965), The Ugly Dachshund (1966), and The Love Bug (1968).[120][121] Disney's last child actor of the 1960s was Kurt Russell, who had signed a ten-year contract.[122] He featured in films such as The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes (1969), The Horse in the Gray Flannel Suit (1968) alongside Dean Jones, The Barefoot Executive (1971), and The Strongest Man in the World (1975).[123]

In late 1959, Walt had an idea to build another park in Palm Beach, Florida, called the City of Tomorrow, a city that would be full of technological improvements.[124] In 1964, the company chose land southwest of Orlando, Florida to build the park and acquired 27,000 acres (10,927 ha). On November 15, 1965, Walt, along with Roy and Florida's governor Haydon Burns, announced plans for a park called Disney World, which included Magic Kingdom—a larger version of Disneyland—and the City of Tomorrow, at the park's center.[125] By 1967, the company had made expansions to Disneyland, and more rides were added in 1966 and 1967, at a cost of $20 million.[126] The new rides included Walt Disney's Enchanted Tiki Room, which was the first attraction to use Audio-Animatronics; Walt Disney's Carousel of Progress, which debuted at the 1964 New York World's Fair before moving to Disneyland in 1967; and Dumbo the Flying Elephant.[127]

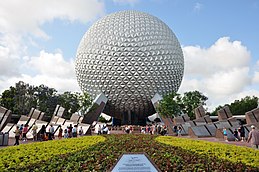

On November 20, 1964, Walt sold most of WED Enterprise to Walt Disney Productions for $3.8 million after being persuaded by Roy, who thought Walt having his own company would cause legal problems. Walt formed a new company called Retlaw to handle his personal business, primarily Disneyland Railroad and Disneyland Monorail.[128] When the company started looking for a sponsor for the project, Walt renamed the City of Tomorrow, Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (Epcot).[129] Walt, who had been a heavy smoker since World War I, fell very sick and he died on December 15, 1966, aged 65, of lung cancer, at St. Joseph Hospital across the street from the studio.[130][131]

1967–1984: Roy O. Disney's leadership and death, Walt Disney World, animation industry decline, and Touchstone Pictures

In 1967, the last two films Walt had worked on were released; the animated film The Jungle Book, which was Disney's most successful film for the next two decades, and the live-action musical The Happiest Millionaire.[132][133] After Walt's death, the company largely abandoned animation, but made several live-action films.[134][135] Its animation staff declined from 500 to 125 employees, with the company only hiring 21 people from 1970 to 1977.[136]

Disney's first post-Walt animated film The Aristocats was released in 1970; according to Dave Kehr of Chicago Tribune, "the absence of his [Walt's] hand is evident".[137] The following year, the anti-fascist musical Bedknobs and Broomsticks was released and won the Oscar for Best Special Visual Effects.[138] At the time of Walt's death, Roy was ready to retire but wanted to keep Walt's legacy alive; he became the first CEO and chairman of the company.[139][140] In May 1967, Roy had legislation passed by Florida's legislatures to grant Disney World its own quasi-government agency in an area called Reedy Creek Improvement District. Roy changed Disney World's name to Walt Disney World to remind people it was Walt's dream.[141][142] EPCOT became less the City of Tomorrow, and more another amusement park.[143]

After 18 months of construction at a cost of around $400 million, Walt Disney World's first park the Magic Kingdom, along with Disney's Contemporary Resort and Disney's Polynesian Resort,[144] opened on October 1, 1971, with 10,400 visitors. A parade with over 1,000 band members, 4,000 Disney entertainers, and a choir from the US Army marched down Main Street. The icon of the park was the Cinderella Castle. On Thanksgiving Day, cars traveling to the Magic Kingdom caused traffic jams along interstate roads.[145][146]

On December 21, 1971, Roy died of cerebral hemorrhage at St. Joseph Hospital.[140] Donn Tatum, a senior executive and former president of Disney, became the first non-Disney-family-member to become CEO and chairman. Card Walker, who had been with the company since 1938, became its president.[147][148] By June 30, 1973, Disney had over 23,000 employees and a gross revenue of $257,751,000 over a nine-month period, compared to the year before when it made $220,026,000.[149] In November, Disney released the animated film Robin Hood (1973), which became Disney's biggest international-grossing movie at $18 million.[150] Throughout the 1970s, Disney released live-action films such as The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes' sequel Now You See Him, Now You Don't;[151] The Love Bug sequels Herbie Rides Again (1974) and Herbie Goes to Monte Carlo (1977);[152][153] Escape to Witch Mountain (1975);[154] and Freaky Friday (1976).[155] In 1976, Card Walker became CEO of the company, with Tatum remaining chairman until 1980, when Walker replaced him.[139][148] In 1977, Roy E. Disney, Roy O. Disney's son and the only Disney working for the company, resigned as an executive because of disagreements with company decisions.[156]

In 1977, Disney released the successful animated film The Rescuers, which grossed $48 million.[157] The live-acton/animated musical Pete's Dragon was released in 1977, grossing $16 million in the US and Canada, but was a disappointment to the company.[158][159] In 1979, Disney's first PG-rated film and most expensive film to that point at $26 million The Black Hole was released, showing Disney could use special effects. It grossed $35 million, a disappointment to the company, which thought it would be a hit like Star Wars (1977). The Black Hole was a response to other Science fiction films of the era.[160][161]

In September, 12 animators, which was over 15% of the department, resigned. Led by Don Bluth, they left because of a conflict with the training program and the atmosphere, and started their own company Don Bluth Productions.[162][163] In 1981, Disney released Dumbo to VHS and Alice in Wonderland the following year, leading Disney to eventually release all its films on home media.[164] On July 24, Walt Disney's World on Ice, a two-year tour of ice shows featuring Disney charters, made its premiere at the Brendan Byrne Meadowlands Arena after Disney licensed its characters to Feld Entertainment.[165][166] The same month, Disney's animated film The Fox and the Hound was released and became the highest-grossing animated film to that point at $40 million.[167] It was the first film that did not involve Walt and the last major work done by Disney's Nine Old Men, who were replaced with younger animators.[136]

As profits started to decline, on October 1, 1982, Epcot, then known as EPCOT Center, opened as the second theme park in Walt Disney World, with around 10,000 people in attendance during the opening.[168][169] The park cost over $900 million to construct, and consisted of the Future World pavilion and World Showcase representing Mexico, China, Germany, Italy, America, Japan, France, the UK, and Canada; Morocco and Norway were added in 1984 and 1988, respectively.[168][170] The animation industry continued to decline and 69% of the company's profits were from its theme parks; in 1982, there were 12 million visitors to Walt Disney World, a figure that declined by 5% the following June.[168] On July 9, 1982, Disney released Tron, one of the first films to extensively use computer-generated imagery (CGI). It was a big influence on other CGI movies, though it received mixed reviews.[171] In 1982, the company lost $27 million.[172]

On April 15, 1983, Disney's first park outside the US, Tokyo Disneyland, opened in Urayasu.[173] Costing around $1.4 billion, construction started in 1979 when Disney and The Oriental Land Company agreed to build a park together. Within its first ten years, the park had over 140 million visitors.[174] After an investment of $100 million, on April 18, Disney started a pay-to-watch cable television channel called Disney Channel, a 16-hours-a-day service showing Disney films, twelve programs, and two magazines shows for adults. Although it was expected to do well, the company lost $48 million after its first year, with around 916,000 subscribers.[175][176]

In 1983, Walt's son-in-law Ron W. Miller, who had been president since 1978, became its CEO, and Raymond Watson became chairman.[139][177] Miller wanted the studio to produce more content for mature audiences,[178] and Disney founded film distribution label Touchstone Pictures to produce movies geared toward adults and teenagers in 1984.[172] Splash (1984) was the first film released under the label, and a much-needed success, grossing over $6 million in its first week.[179] Disney's first R-rated film Down and Out in Beverly Hills (1986) was released and was another hit, grossing $62 million.[180] The following year, Disney's first PG-13 rated film Adventures in Babysitting was released.[181] In 1984, Saul Steinberg attempted to buy out the company, holding 11% of the stocks. He offered to buy 49% for $1.3 billion or the entire company for $2.75 billion. Disney, which had less than $10 million, rejected Steinberg's offer and offered to buy all of his stock for $326 million. Steinberg agreed, and Disney paid it all with part of a $1.3 billion bank loan, putting the company $866 million in debt.[182][183]

1984–2005: Michael Eisner's leadership, the Disney Renaissance, merger, and acquisitions

In 1984, shareholders Roy E. Disney, Sid Bass, Lillian and Diane Disney, and Irwin L. Jacobs—who together owned about 36% of the shares, forced out CEO Miller and replaced him with Michael Eisner, a former president of Paramount Pictures, and appointed Frank Wells as president.[184] Eisner's first act was to make it a major film studio, which at the time it was not considered. Eisner appointed Jeffrey Katzenberg as chairman and Roy E. Disney as head of animation. Eisner wanted to produce an animated film every 18 months rather than four years, as the company had been doing. To help with the film division, the company started making Saturday-morning cartoons to create new Disney characters for merchandising, and produced films through Touchstone. Under Eisner, Disney became more involved with television, creating Touchstone Television and producing the television sitcom The Golden Girls, which was a hit. The company spent $15 million promoting its theme parks, raising visitor numbers by 10%.[185][186] In 1984, Disney produced The Black Cauldron, then the most-expensive animated movie at $40 million, their first animated film to feature computer-generated imagery, and their first PG-rated animation because of its adult themes. The film was a box-office failure, leading the company to move the animation department from the studio in Burbank to a warehouse in Glendale, California.[187] The film-financing partnership Silver Screen Partners II, which was organized in 1985, financed films for Disney with $193 million. In January 1987, Silver Screen Partners III began financing movies for Disney with $300 million raised by E.F. Hutton, the largest amount raised for a film-financing limited partnership.[188] Silver Screen IV was also set up to finance Disney's studios.[189]

In 1986, the company changed its name from Walt Disney Productions to the Walt Disney Company, stating the old name only referred to the film industry.[190] With Disney's animation industry declining, the animation department needed its next movie The Great Mouse Detective to be a success. It grossed $25 million at the box office, becoming a much-needed financial success.[191] To generate more revenue from merchandising, the company opened its first retail store Disney Store in Glendale in 1987. Because of its success, the company opened two more in California, and by 1990, it had 215 throughout the US[192][193] In 1989, the company garnered $411 million in revenue and made a profit of $187 million.[194] In 1987, the company signed an agreement with the Government of France to build a resort named Euro Disneyland in Paris; it would consist of two theme parks named Disneyland Park and Walt Disney Studios Park, a golf course, and 6 hotels.[195][196]

In 1988, Disney's 27th animated film Oliver & Company was released the same day as that of former Disney animator Don Bluth's The Land Before Time. Oliver & Company out-competed The Land Before Time, becoming the first animated film to gross over $100 million in its initial release, and the highest-grossing animated film in its initial run.[197][198] Disney became the box-office-leading Hollywood studio for the first time, with films such as Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), Three Men and a Baby (1987), and Good Morning, Vietnam (1987). The company's gross revenue went from $165 million in 1983 to $876 million in 1987, and operating income went from −$33 million in 1983 to +130 million in 1987. The studio's net income rose by 66%, along with a 26% growth in revenue. Los Angeles Times called Disney's recovery "a real rarity in the corporate world".[199] On May 1, 1989, Disney opened Disney-MGM Studios, its third amusement park at Walt Disney World, and later became Hollywood Studios. The new park demonstrated to visitors the movie-making process, until 2008, when it was changed to make guests feel they are in movies.[200] Following the opening of Disney-MGM Studios, Disney opened the water park Typhoon Lagoon in June 1989; in 2022 it had 1.9 million visitors and was the most popular water park in the world.[201][202] Also in 1989, Disney signed an agreement-in-principle to acquire The Jim Henson Company from its founder. The deal included Henson's programming library and Muppet characters—excluding the Muppets created for Sesame Street—as well as Henson's personal creative services. Henson, however, died in May 1990 before the deal was completed, resulting in the companies terminating merger negotiations.[203][204][205]

On November 17, 1989, Disney released The Little Mermaid, which was the start of the Disney Renaissance, a period in which the company released hugely successful and critically acclaimed animated films. The Little Mermaid became the animated film with the highest gross from its initial run and garnered $233 million at the box office; it won two Academy Awards; Best Original Score and Best Original Song for "Under the Sea".[206][207] During the Disney Renaissance, composer Alan Menken and lyricist Howard Ashman wrote several Disney songs until Ashman died in 1991. Together they wrote 6 songs nominated for Academy Awards; with two winning songs—"Under the Sea" and "Beauty and the Beast".[208][209] To produce music geared for the mainstream, including music for movie soundtracks, Disney founded the recording label Hollywood Records on January 1, 1990.[210][211] In September 1990, Disney arranged for financing of up to $200 million by a unit of Nomura Securities for Interscope films made for Disney. On October 23, Disney formed Touchwood Pacific Partners, which replaced the Silver Screen Partnership series as the company's movie studios' primary source of funding.[189] Disney's first animated sequel The Rescuers Down Under was released on November 16, 1990, and created using Computer Animation Production System (CAPS), digital software developed by Disney and Pixar—the computer division of Lucasfilm—becoming the first feature film to be entirely created digitally.[207][212] Although the film struggled in the box office, grossing $47 million, it received positive reviews.[213][214] In 1991, Disney and Pixar agreed to a deal to make three films together, the first one being Toy Story.[215]

Dow Jones & Company, wanting to replace 3 companies in its industrial average, chose to add Disney in May 1991, stating Disney "reflects the importance of entertainment and leisure activities in the economy".[216] Disney's next animated film Beauty and the Beast was released on November 13, 1991, and grossed nearly $430 million.[217][218] It was the first animated film to win a Golden Globe for Best Picture, and it received 6 Academy Award nominations, becoming the first animation nominated for Best Picture; it won Best Score, Best Sound, and Best Song.[219] The film was critically acclaimed, with some critics considering it to be the best Disney film.[220][221] To coincide with the 1992 release of The Mighty Ducks, Disney founded the National Hockey League team The Mighty Ducks of Anaheim.[222] Disney's next animated feature Aladdin was released on November 11, 1992, and grossed $504 million, becoming the highest-grossing animated film to that point, and the first animated film to gross a half-billion dollars.[223][224] It won two Academy Awards—Best Song for "A Whole New World" and Best Score;[225] and "A Whole New World" was the first-and-only Disney song to win the Grammy for Song of the Year.[226][227] For $60 million, Disney broadened its range of mature-audience films by acquiring independent film distributor Miramax Films in 1993.[228] The same year, in a venture with The Nature Conservancy, Disney purchased 8,500 acres (3,439 ha) of Everglades headwaters in Florida to protect native animals and plant species, establishing the Disney Wilderness Preserve.[229]

On April 3, 1994, Frank Wells died in a helicopter crash; he, Eisner, and Katzenberg helped the company's market value go from $2 billion to $22 billion since taking office in 1984.[230] On June 15 the same year, The Lion King was released and was a massive success, becoming the second-highest-grossing film of all time behind Jurassic Park and the highest-grossing animated film of all time, with a gross total of $969 million.[231][232] It was critically praised and garnered two Academy Awards—Best Score and Best Song for "Can You Feel the Love Tonight".[233][234] Soon after its release, Katzenberg left the company after Eisner refused to promote him to president. After leaving, he co-founded film studio DreamWorks SKG.[235] Wells was later replaced with one of Eisner's friends Michael Ovitz on August 13, 1995.[236][237] In 1994, Disney wanted to buy one of the major U.S. television networks ABC, NBC, or CBS, which would give the company guaranteed distribution for its programming. Eisner planned to buy NBC but the deal was canceled because General Electric wanted to keep a majority stake.[238][239] In 1994, Disney's annual revenue reached $10 billion, 48% coming from film, 34% from theme parks, and 18% from merchandising. Disney's total net income was up 25% from the previous year at $1.1 billion.[240] Grossing over $346 million, Pocahontas was released on June 16, garnering the Academy Awards for Best Musical or Comedy Score and Best Song for "Colors of the Wind".[241][242] Pixar's and Disney's first co-release was the first-ever fully computer-generated film Toy Story, which was released on November 19, 1995, to critical acclaim and an end-run gross total of $361 million. The film won the Special Achievement Academy Award and was the first animated film to be nominated for Best Original Screenplay.[243][244]

In 1995, Disney announced the $19 billion acquisition of television network Capital Cities/ABC Inc., which was then the 2nd-largest corporate takeover in US history. Through the deal, Disney would obtain broadcast network ABC, an 80% majority stake in sports networks ESPN and ESPN 2, 50% in Lifetime Television, a majority stake of DIC Entertainment, and a 38% minority stake in A&E Television Networks.[240][245][246] Following the deal, the company started Radio Disney, a youth-focused radio program on ABC Radio Network, on November 18, 1996.[247][248] The Walt Disney Company launched its official website disney.com on February 22, 1996, mainly to promote its theme parks and merchandise.[249] On June 19, the company's next animated film The Hunchback of Notre Dame was released, grossing $325 million at the box office.[250] Because Ovitz's management style was different from Eisner's, Ovitz was fired as the company's president in 1996.[251] Disney lost a $10.4 million lawsuit in September 1997 to Marsu B.V. over Disney's failure to produce as contracted 13 half-hour Marsupilami cartoon shows. Instead, Disney felt other internal "hot properties" deserved the company's attention.[252] Disney, which since 1996 had owned a 25% stake in the Major League Baseball team California Angels, bought out the team in 1998 for $110 million, renamed it Anaheim Angels and renovated the stadium for $100 million.[253][254] Hercules (1997) was released on June 13, and underperformed compared to earlier films, grossing $252 million.[255] On February 24, Disney and Pixar signed a ten-year contract to make five films, with Disney as distributor. They would share the cost, profits, and logo credits, calling the films Disney-Pixar productions.[256] During the Disney Renaissance, film division Touchstone also saw success with film such as Pretty Woman (1990), which has the highest number of ticket sales in the U.S. for a romantic comedy and grossed $432 million;[257][258] Sister Act (1992), which was one of the financially successful comedies of the early 1990s, grossing $231 million;[259] action film Con Air (1997), which grossed $224 million;[260] and the highest-grossing film of 1998 at $553 million Armageddon.[261]

At Disney World, the company opened Disney's Animal Kingdom, the largest theme park in the world covering 580 acres (230 ha) on Earth Day, April 22, 1998. It had six animal-themed lands, over 2,000 animals, and the Tree of Life at its center.[262][263] Receiving positive reviews, Disney's next animated films Mulan and Disney-Pixar film A Bug's Life were released on June 5 and November 20, 1998.[264][265] Mulan became the year's sixth-highest-grossing film at $304 million, and A Bug's Life was the year's fifth-highest at $363 million.[261] In a $770-million transaction, on June 18, Disney bought a 43% stake of Internet search engine Infoseek for $70 million, also giving it Infoseek-acquired Starwave.[266][267] Starting web portal Go.com in a joint venture with Infoseek in January 1999, Disney acquired the rest of Infoseek later that year.[268][269] After unsuccessful negotiations with cruise lines Carnival and Royal Caribbean International, in 1994, Disney announced it would start its own cruise-line operation in 1998.[270][271] The first two ships of the Disney Cruise Line were named Disney Magic and Disney Wonder, and built by Fincantieri in Italy. To accompany the cruises, Disney bought Gorda Cay as the line's private island, and spent $25 million remodeling it and renaming it Castaway Cay. On July 30, 1998, Disney Magic set sail as the line's first voyage.[272]

Marking the end of the Disney Renaissance, Tarzan (1999) was released on June 12, garnering $448 million at the box office and critical acclaim; it claimed the Academy Award for Best Original Song for Phil Collins' "You'll Be in My Heart".[273][274][275][276] Disney-Pixar film Toy Story 2 was released on November 13, garnering praise and $511 million at the box office.[277][278] To replace Ovitz, Eisner named ABC network chief Bob Iger Disney's president and chief operating officer in January 2000.[279][280] In November, Disney sold DIC Entertainment back to Andy Heyward.[281] Disney had another huge success with Pixar when they released Monsters, Inc. in 2001. Later, Disney bought children's cable network Fox Family Worldwide for $3 billion and the assumption of $2.3 billion in debt. The deal included a 76% stake in Fox Kids Europe, Latin American channel Fox Kids, more than 6,500 episodes from Saban Entertainment's programming library, and Fox Family Channel.[282] In 2001, Disney's operations had a net loss of $158 million after a decline in viewership of the ABC television network, as well as decreased tourism due to the September 11 attacks. Disney earnings in fiscal 2001 were $120 million compared with the previous year's $920 million. To help reduce costs, Disney announced it would lay off 4,000 employees and close 300–400 Disney stores.[283][284] After winning the World Series in 2002, Disney sold the Anaheim Angels for $180 million in 2003.[285][286] In 2003, Disney became the first studio to garner $3 billion in a year at the box office.[287] The same year, Roy Disney announced his retirement because of how the company was being run, calling on Eisner to retire; the same week, board member Stanley Gold retired for the same reasons. Gold and Disney formed the "Save Disney" campaign.[288][289]

In 2004, at the company's annual meeting, the shareholders in a 43% vote voted Eisner out as chairman.[290] On March 4, George J. Mitchell, who was a member of the board, was named as replacement.[291] In April, Disney purchased the Muppets franchise from the Jim Henson Company for $75 million, founding Muppets Holding Company, LLC.[292][293] Following the success of Disney-Pixar films Finding Nemo (2003), which became the second highest-grossing animated film of all time at $936 million, and The Incredibles (2004),[294][295] Pixar looked for a new distributor once its deal with Disney ended in 2004.[296] Disney sold the loss-making Disney Stores chain of 313 stores to Children's Place on October 20.[297] Disney also sold the NHL team Mighty Ducks in 2005.[298] Roy E. Disney decided to rejoin the company and was given the role of consultant with the title "Director Emeritus".[299]

2005–2020: Bob Iger's first tenure, expansion and Disney+

In March 2005, Bob Iger, president of the company, became CEO after Eisner's retirement in September; Iger was officially named head of the company on October 1.[300][301] Disney's eleventh theme park Hong Kong Disneyland opened on September 12, costing the company $3.5 billion to construct.[302] On January 24, 2006, Disney began talks to acquire Pixar from Steve Jobs for $7.4 billion, and Iger appointed Pixar chief creative officer (CCO) John Lasseter and president Edwin Catmull the heads of the Walt Disney Animation Studios.[303][304] A week later, Disney traded ABC Sports commentator Al Michaels to NBCUniversal, in exchange for the rights to Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and 26 cartoons featuring the character.[305] On February 6, the company announced it would be merging its ABC Radio networks and 22 stations with Citadel Broadcasting in a $2.7 billion deal, though which Disney acquired 52% of television broadcasting company Citadel Communications.[306][307] The Disney Channel movie High School Musical aired and its soundtrack was certified triple platinum, becoming the first Disney Channel film to do so.[308]

Disney's 2006 live-action film Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest was Disney's biggest hit to that date and the third-highest-grossing film ever, making $1 billion at the box office.[309] On June 28, the company announced it was replacing George Mitchell as chairman with a board members and former CEO of P&G John E. Pepper Jr..[291] The sequel High School Musical 2 was released in 2007 on Disney Channel and broke several cable rating records.[310] In April 2007, the Muppets Holding Company was moved from Disney Consumer Products to the Walt Disney Studios division and renamed the Muppets Studios to relaunch the division.[311][312] Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End became the highest-grossing film of 2007 at $960 million.[313] Disney-Pixar films Ratatouille (2007) and WALL-E (2008) were a tremendous success, with WALL-E winning the Oscar for Best Animated Feature.[314][315][316] After acquiring most of Jetix Europe through the acquisition of Fox Family Worldwide, Disney bought the remainder of the company in 2008 for $318 million.[317]

Iger introduced D23 in 2009 as Disney's official fan club.[318][319] In February, Disney announced a deal with DreamWorks Pictures to distribute 30 of their films over the next five years through Touchstone Pictures, with Disney getting 10% of the gross.[320][321] The 2009 film Up garnered Disney $735 million at the box office, and the film won Best Animated Feature at the Academy Awards.[322][323] Later that year, Disney launched a television channel named Disney XD, aimed at older children.[324] The company bought Marvel Entertainment and its assets for $4 billion in August, adding Marvel's comic-book characters to its merchandising line-up.[325] In September, Disney partnered with News Corporation and NBCUniversal in a deal in which all parties would obtain 27% equity in streaming service Hulu, and Disney added ABC Family and Disney Channel to the streaming service.[326] On December 16, Roy E. Disney died of stomach cancer; he was the last member of the Disney family to work for Disney.[327] In March 2010, Haim Saban reacquired from Disney the Power Rangers franchise, including its 700-episode library, for around $100 million.[328][329] Shortly after, Disney sold Miramax Films to an investment group headed by Ronald Tutor for $660 million.[330] During that time, Disney released the live-action Alice in Wonderland and the Disney-Pixar film Toy Story 3, both of which grossed a little over $1 billion, making them the sixth-and-seventh films to do so; and Toy Story 3 became the first animated film to make over $1 billion and the highest-grossing animated film. That year, Disney became the first studio to release two $1-billion-dollar-earning films in one calendar year.[331][332] In 2010, the company announced ImageMovers Digital, which it started in partnership with ImageMovers in 2007, would be closing by 2011.[333]

The following year, Disney released its last traditionally animated film Winnie the Pooh to theaters.[334] The release of Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides garnered a little over $1 billion, making it the eighth film to do so and Disney's highest-grossing film internationally, as well as the third-highest ever.[335] In January 2011, the size of Disney Interactive Studios was reduced and 200 employees laid off.[336] In April, Disney began constructing its new theme park Shanghai Disney Resort, costing $4.4 billion.[337] In August, Iger stated after the success of the Pixar and Marvel purchases, he and the Walt Disney Company were planning to "buy either new characters or businesses that are capable of creating great characters and great stories".[338] On October 30, 2012, Disney announced it would buy Lucasfilm for $4.05 billion from George Lucas. Through the deal, Disney gained access to franchises such as Star Wars, for which Disney said it would make a new film for every two-to-three years, with the first being released in 2015. The deal gave Disney access to the Indiana Jones franchise, visual-effects studio Industrial Light & Magic, and video game developer LucasArts.[339][340][341]

In February 2012, Disney completed its acquisition of UTV Software Communications, expanding its market into India and the rest of Asia.[342] By March, Iger became Disney's chairman.[343] Marvel film The Avengers became the third-highest-grossing film of all time with an initial-release gross of $1.3 billion.[344] Making over $1.2 billion at the box office, the Marvel film Iron Man 3 was released in 2013.[345] The same year, Disney's animated film Frozen was released and became the highest-grossing animated film of all time at $1.2 billion.[346][347] Merchandising for the film became so popular it made the company $1 billion within a year, and a global shortage of merchandise for the film occurred.[348][349] In March 2013, Iger announced Disney had no 2D animation films in development, and a month, later the hand-drawn animnation division was closed, and several veteran animators were laid off.[334] On March 24, 2014, Disney acquired Maker Studios, an active multi-channel network on YouTube, for $950 million.[350]

In June 2015, the company stated its consumer products and interactive divisions would merge to become new a subsidiary called Disney Consumer Products and Interactive Media.[351] In August, Marvel Studios was placed under the Walt Disney Studios division.[352] The company's 2015 releases include the successful animated film Inside Out, which grossed over $800 million, and the Marvel film Avengers: Age of Ultron, which grossed over $1.4 billion.[353] Star Wars: The Force Awakens was released and grossed over $2 billion, making it the third-highest-grossing film of all time.[354] On April 4, 2016, Disney announced COO Thomas O. Staggs, who was thought to be next in line after Iger, would leave in May, ending his 26-year career with Disney.[355] Shanghai Disneyland opened on June 16, 2016, as the company's sixth theme-park resort.[356] In a move to start a streaming service, Disney bought 33% of the stock in Major League Baseball technology company Bamtech for $1 billion in August.[357] In 2016, four Disney film releases made over $1 billion; these were the animated film Zootopia, Marvel film Captain America: Civil War, Pixar film Finding Dory, and Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, making Disney the first studio to surpass $3 billion at the domestic box office.[358][359] Disney made an attempt to buy social media platform Twitter to market their content and merchandise but canceled the deal. Iger stated this was because he thought Disney would be taking on responsibilities it did not need and that it did not "feel Disney" to him.[360]

On March 23, 2017, Disney announced Iger had agreed to a one-year extension as CEO to July 2019, and to remain as a consultant for three years.[361][362] On August 8, 2017, Disney announced it would be ending its distribution deal with Netflix, with the intent of launching its own streaming platform by 2019. During that time, Disney paid $1.5 billion to acquire a 75% stake in BAMtech. Disney planned to start an ESPN streaming service with about "10,000 live regional, national, and international games and events a year" by 2018.[363][364] In November, CCO John Lasseter said he would take a 6-month absence because of "missteps", reported to be sexual misconduct allegations.[365] The same month, Disney and 21st Century Fox started negotiating a deal in which Disney would acquire most of Fox's assets.[366] Beginning in March 2018, a reorganization of the company led to the creation of business segments Disney Parks, Experiences and Products and Direct-to-Consumer & International. Parks & Consumer Products was primarily a merger of Parks & Resorts and Consumer Products & Interactive Media, while Direct-to-Consumer & International took over for Disney International and global sales, distribution, and streaming units from Disney-ABC TV Group and Studios Entertainment plus Disney Digital Network.[367] Iger described it as "strategically positioning our businesses" while according to The New York Times, the reorganization was done in expectation of the 21st Century Fox purchase.[368]

In 2017, two of Disney's films had revenues of over $1 billion; the live-action Beauty and the Beast and Star Wars: The Last Jedi.[369][370] Disney launched subscription sports streaming service ESPN+ on April 12.[371] In June 2018, Lasseter's departure by the end of the year was announced; he would stay as a consultant until then.[372] To replace him; Disney promoted Jennifer Lee, co-director of Frozen and co-writer of Wreck-It Ralph (2012), as head of Walt Disney Animation Studios; and Pete Docter, who had been with Pixar since 1990 and directed Up,Monsters, Inc., and Inside Out, as head of Pixar.[373][374] Comcast offered to buy 21st Century Fox for $65 billion over Disney's $51 billion bid but withdrew its offer after Disney countered with a $71 billion bid. Disney obtained antitrust approval from the United States Department of Justice to acquire Fox.[375][376] Disney again made $7 billion at the box office with three film that made $1 billion; Marvel films Black Panther and Avengers: Infinity War—the latter taking over $2 billion and becoming the fifth-highest-grossing film ever— and Pixar film Incredibles 2.[377][378]

On March 20, 2019, Disney acquired 21st Century Fox's assets for $71 billion from Rupert Murdoch, making it the biggest acquisition in Disney's history. After the purchase, The New York Times described Disney as "an entertainment colossus the size of which the world has never seen".[379] Through the acquisition, Disney gained 20th Century Fox; 20th Century Fox Television; Fox Searchlight Pictures; National Geographic Partners; Fox Networks Group; Indian television broadcaster Star India; streaming service Hotstar; and a 30% stake in Hulu, bringing its ownership on Hulu to 60%. Fox Corporation and its assets were excluded from the deal because of antitrust laws.[380][381] Disney became the first film studio to have seven films gross $1 billion: Marvel's Captain Marvel, the live action Aladdin, Pixar's Toy Story 4, the CGI remake of The Lion King, Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker, and the highest-grossing film of all time up to that point at $2.8 billion Avengers: Endgame.[382][383] On November 12, Disney's subscription video on-demand over-the-top streaming service Disney+, which had 500 movies and 7,500 episodes of television shows from Disney, Pixar, Marvel, Star Wars, National Geographic, and other brands, was launched in the US, Canada and the Netherlands. Within the first day, the streaming platform had over 10 million subscriptions; and by 2022 it had over 135 million and was available in over 190 countries.[384][385] At the beginning of 2020, Disney removed the Fox name from its assets, rebranding them as 20th Century Studios and Searchlight Pictures.[386]

2020–present: Bob Chapek's leadership, COVID-19 pandemic, Iger's return & 100th anniversary

Bob Chapek, who had been with the company for 18 years and was chairman of Disney Parks, Experiences and Products, became CEO after Iger resigned on February 25, 2020. Iger said he would stay as an Executive chairman until December 31, 2021, to help with its creative strategy.[387][388] In April, Iger resumed operational duties as executive chairman to help the company during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Chapek was appointed to the board of directors.[389][390] During the pandemic, Disney temporarily closed all its theme parks, delayed the release of several movies, and stopped all cruises.[391][392][393] Due to the closures, Disney announced it would stop paying 100,000 employees but still provide healthcare benefits, and urged US employees to apply for government benefits, saving the company $500 million a month. Iger gave up his $47 million salary and Chapek took a 50% salary reduction.[394]

In the company's second fiscal quarter of 2020, Disney reported a $1.4 billion loss, with a fall in earnings of 91% to $475 million from the previous year's $5.4 billion.[395] By August, two-thirds of the company was owned by large financial institutions.[396] In September, the company dismissed 28,000 employees, 67% of whom were part-time, from its Parks, Experiences and Products division. Chairman of the division Josh D'Amaro wrote; "We initially hoped that this situation would be short-lived, and that we would recover quickly and return to normal. Seven months later, we find that has not been the case." Disney lost $4.7 billion in its fiscal third quarter of 2020.[397] In November, Disney laid off another 4,000 employees, raising the total to 32,000 employees.[398] The following month, Disney named Alan Bergman as chairman of its Disney Studios Content division to oversee its film studios.[399] Due to the COVID-19 recession, Touchstone Television ceased operations in December,[400] Disney announced in March 2021 it would be launching a new division called 20th Television Animation to focus on mature audiences,[401] and Disney closed its third animation studio Blue Sky Studios in April 2021.[402] Later that month, Disney and Sony agreed a multi-year licensing deal that would give Disney access to Sony's films from 2022 to 2026 to televise or stream on Disney+ once Sony's deal with Netflix ended.[403] Although it performed poorly at the box office because of Covid, Disney's animated film Encanto (2021) was one of the biggest hits during the pandemic, with its song "We Don't Talk About Bruno" topping the US Billboard Hot 100 charts.[404][405]

After Iger's term as executive chairman ended on December 31, he announced he would resign as chairman. The company brought in an operating executive at The Carlyle Group and former board member Susan Arnold as Disney's first female chairperson.[406] On March 10, Disney ceased operations in Russia because of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and was the first major Hollywood studio to halt release of a major picture due to Russia's invasion; other movie studios followed.[407] In March 2022, around 60 employees protested the company's silence on the Florida Parental Rights in Education Act that was dubbed the Don't Say Gay Bill, and prohibits non-age-appropriate classroom instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity in Florida's public-school districts. The protest was dubbed the "Disney Do Better Walkout"; employees protested near a Disney Studios lot, and other employees voiced their concerns through social media. Employees called on Disney to stop campaign contributions to Florida politicians who supported the bill, to help protect employees from it, and to stop construction at Walt Disney World in Florida. Chapek responded by stating the company had made a mistake by staying silent and said; "We pledge our ongoing support of the LGBTQ+ community".[408][409] Amid Disney's response to the bill, the Florida Legislature passed a bill to remove Disney's quasi-government district Reedy Creek.[410]

On June 28, Disney's board members unanimously agreed to give Chapek a three-year contract extension.[411] In August, Disney Streaming exceeded Netflix in total subscriptions with 221 million subscribers compared to Netflix's 220 million.[412]

On November 20, 2022, Iger accepted the position of Disney's CEO after Chapek was dismissed following poor earnings performance and decisions unpopular with other executives.[413][414] The board announced Iger would serve for two years with a mandate to develop a strategy for renewed growth and help identify a successor.[415]

In November 2022, a group of YouTube TV subscribers in four states filed a class-action antitrust lawsuit against Disney, alleging that Disney's control of both ESPN and Hulu allowed the company to "inflate prices marketwise by raising the prices of its own products" and by requiring streaming services including YouTube TV and Sling TV to include ESPN in base packages, forcing subscribers to pay more for subscriptions than they would in a competitive market.[416][417]

In January 2023, Disney announced that Mark Parker would replace Arnold as the company's chairperson.[418] In February 2023, Disney announced that it would be cutting $5.5 billion in costs, which includes eliminating 7,000 jobs representing 3% of its workforce. Disney reorganized into three divisions: Entertainment, ESPN, and Parks, Experiences and Products.[419] In April 2023, Disney implemented the second and largest wave of job cuts, affecting Disney Parks, Disney Entertainment, ESPN, and the Experiences and Product division. This move was part of the plan to cut costs by $5.5 billion.[420]

In 2023, Disney began its "100 Years of Wonder" campaign in celebration of the centennial anniversary of the company's founding. This included a new animated centennial logo intro for the Walt Disney Pictures division, a touring exhibition, events at the parks and a commemorative commercial that aired during Super Bowl LVII.[421][422]

In October 2023, Disney announced its entrance into sports betting through a partnership with Penn Entertainment, launching the ESPN Bet app, despite internal debates and concerns over brand image. This move marked a significant pivot from Iger's earlier stance against gambling, driven by the potential to attract younger audiences and secure a financial future for ESPN, amidst declining traditional TV viewership and increasing online sports gambling revenue.[423] In November 2023, Disney shortened the lengthy name of Disney Parks, Experiences and Products to Disney Experiences.[424]

In February 2024, Debra O'Connell, a longtime executive at Disney, was appointed president of a new news division that would include ABC News and local stations. O'Connell is responsible for ABC News's signature properties, including Good Morning America and World News Tonight. It will serve as an intermediary between Dana Walden, co-chair of Disney Entertainment and Kim Godwin, the ABC News president. Other online news units have similar processes.[425] In February, Walt Disney and Reliance Industries announced the merger of their India TV and streaming media assets.[426]

In July 2024, a hacker group called "NullBulge" allegedly stole and leaked over a terabyte of the company's Slack messages. The motive for the breach appeared to be the group's dislike of art generated by artificial intelligence.[427]

Members of Generation Z were notably absent from the D23 fan event held in August 2024 in Anaheim, which was dominated by millennials representing all 50 U.S. states and 36 countries.[428] Disney chief brand officer Asad Ayaz pushed back against the idea that this was a symptom of a broader trend: "Our fandoms and our fans and different generations show up in different ways".[428] Theme park experts noted that the true test of the enduring power of the Disney brand will be whether Generation Z takes Generation Alpha to Disney theme parks.[428]

In October 2024, Disney announced James P. Gorman would replace Mark Parker as chairman in January 2025. It also announced a successor to CEO Bob Iger would be named in early 2026.[429]

Company units

The Walt Disney Company operates three primary business segments:

- Disney Entertainment oversees the company's full portfolio of entertainment media and content businesses globally, including the Walt Disney Studios, Disney General Entertainment Content, Disney Streaming and Disney Platform Distribution. The division is led by Alan Bergman and Dana Walden.

- ESPN is responsible for the management and supervision of the company's portfolio of sports content, products, and experiences across all of Disney's platforms worldwide, including its international sports channels. The division is led by James Pitaro.

- Disney Experiences is responsible for theme parks and resorts, cruise and vacation experiences, and consumer products such as toys, apparel, books, and video games. The division is led by Josh D'Amaro.

Leadership

Current

- Board of directors[430]

- Mark Parker (Chairman)

- Mary Barra

- Amy Chang

- Jeremy Darroch

- Carolyn Everson

- Michael Froman

- James P. Gorman

- Bob Iger

- Maria Elena Lagomasino

- Calvin McDonald

- Derica W. Rice

- Executives[430]

- Bob Iger, Chief Executive Officer

- Asad Ayaz, Chief Brand Officer

- Alan Bergman, Co-Chairman, Disney Entertainment

- Sonia Coleman, Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Human Resources Officer

- Tinisha Agramonte, Senior Vice President and Chief Diversity Officer

- David Bowdich, Senior Vice President and Chief Security Officer

- Josh D'Amaro, Chairman, Disney Experiences

- Horacio Gutierrez, Senior Executive Vice President, Chief Legal and Compliance Officer

- Jolene Negre, Associate General Counsel and Secretary

- Hugh Johnston, Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer

- Carlos A. Gómez, Executive Vice President, Corporate Finance and Treasurer

- Brent Woodford, Executive Vice President, Controllership, Finance and Tax

- James Pitaro, Chairman, ESPN

- Kristina Schake, Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Communications Officer

- Dana Walden, Co-Chairman, Disney Entertainment

Past leadership

- Executive chairmen

- Bob Iger (2020–2021)

- Chairmen

- Walt Disney (1945–1960)

- Roy O. Disney (1964–1971)

- Donn Tatum (1971–1980)

- Card Walker (1980–1983)

- Raymond Watson (1983–1984)

- Michael Eisner (1984–2004)

- George J. Mitchell (2004–2006)

- John E. Pepper Jr. (2007–2012)

- Bob Iger (2012–2021)

- Susan Arnold (2022–2023)

- Mark Parker (2023–present)

- Vice chairmen

- Roy E. Disney (1984–2003)

- Sanford Litvack (1999–2000)[a][431]

- Presidents

- Walt Disney (1923–1945)

- Roy O. Disney (1945–1968)

- Donn Tatum (1968–1971)

- Card Walker (1971–1980)

- Ron W. Miller (1980–1984)

- Frank Wells (1984–1994)

- Michael Ovitz (1995–1997)

- Michael Eisner (1997–2000)

- Bob Iger (2000–2012)

- Chief executive officers (CEO)

- Roy O. Disney (1929–1971)

- Donn Tatum (1971–1976)

- Card Walker (1976–1983)

- Ron W. Miller (1983–1984)

- Michael Eisner (1984–2005)

- Bob Iger (2005–2020; 2022–present)

- Bob Chapek (2020–2022)

- Chief operating officers (COO)

- Card Walker (1968–1976)

- Ron W. Miller (1980–1984)

- Frank Wells (1984–1994)

- Thomas O. Staggs (2015–2016)

Awards and nominations

As of 2022, the Walt Disney Company has won 135 Academy Awards, 32 of them were awarded to Walt. The company has won 16 Academy Awards for Best Animated Short Film, 16 for Best Original Song, 15 for Best Animated Feature, 11 for Best Original Score, 5 for Best Documentary Feature, 5 for Best Visual Effects, and several others as well special awards.[432] Disney has also won 29 Golden Globe Awards, 51 British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) awards, and 36 Grammy Awards as of 2022.[433][434][435][b]

Legacy

The Walt Disney Company is one of the world's largest entertainment companies and is considered to be a pioneer in the animation industry, having produced 790 features, 122 of which are animated films.[454][455] Many of their films are considered to be the greatest of all time, including Pinocchio, Toy Story, Bambi, Ratatouille, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and Mary Poppins.[456][457][458] Disney has also created some of the most influential and memorable characters of all time, such as Mickey Mouse, Woody, Captain America (MCU), Jack Sparrow, Iron Man (MCU), and Elsa.[18][459][460]

Disney has been recognized for revolutionizing the animation industry; according to Den of Geek, the risk of making the first animated feature Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs has "changed cinema".[461] The company, mainly through Walt, has introduced new technologies and more-advanced techniques for animating, as well as adding personalities to characters.[462][133] Some of Disney's technological innovations for animation include invention of the multiplane camera, xerography, CAPS, deep canvas, and RenderMan.[212] Many songs from the company's films have become extremely popular, and several have peaked at number one on Billboard's Hot 100.[463] Some songs from the Silly Symphony series became immensely popular across the U.S.[27]

Disney has been ranked number 48 in the 2023 Fortune 500 list of the largest United States corporations by total revenue and fourth in Fortune's 2022 "World's Most Admired Companies".[1][464] According to Smithsonian Magazine, there are "few symbols of pure Americana more potent than the Disney theme parks", which are "well-established cultural icons", with the company name and Mickey Mouse being "household names".[465] Disney is one of the biggest competitors in the theme park industry with 12 parks, all of which were the top-25 most-visited parks in 2018. Disney theme parks worldwide had over 157 million visitors, making it the most-visited theme-park company in the world, doubling the attendance number of the second-most-visited company. Of the 157 million visitors, the Magic Kingdom had 20.8 million of the guests, making it the most-visited theme park in the world.[466][467] When Disney first entered the theme park industry, CNN stated: "It changed an already legendary company. And it changed the entire theme park industry."[468] According to The Orange County Register, Walt Disney World has "changed entertainment by showing how a theme park could help make a company into a lifestyle brand".[469]

Criticism and controversies

The Walt Disney Company has been criticized for making purportedly sexist and racist content in the past, putting LGBT+ elements in their films, and not having enough LGBT+ representation. There have been controversies over alleged plagiarism, poor pay and working conditions, and poor treatment of animals. Disney has also been criticised for filming in the autonomous region of Xinjiang, where human rights abuses are taking place.[470]

Moral partiality

In October 2023, The Walt Disney Company pledged $2 million for humanitarian relief efforts in Israel, following a series of attacks by the occupation resistance group Hamas. Disney allocated half of this donation to Magen David Adom, Israel's national emergency medical service, and the other half to various non-profit organizations supporting children in Israel. Disney CEO Bob Iger described the donation as a means of supporting innocent people in Israel, particularly children without giving any attention to the tens of thousands of Palestinian children that were killed in the conflict. However, the move sparked significant backlash from activists and critics, who argued that Disney’s contributions overlooked the extensive humanitarian crisis in Gaza, where ongoing Israeli airstrikes had killed thousands of Palestinian civilians, including children, and destroyed critical infrastructure. Critics contended that Disney’s selective aid sends a message that Israeli lives, particularly Israeli children's lives, are valued more than those of Palestinians. In addition to the $2 million, Disney implemented a matching gift program for employees, a decision that further fueled public outcry over the company’s perceived endorsement of one side in the conflict.[471][472][473]

Racism