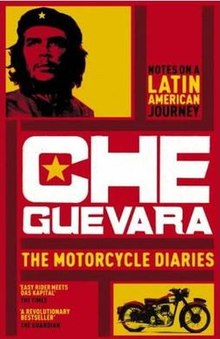

The Motorcycle Diaries (book)

| |

| Author | Ernesto "Che" Guevara |

|---|---|

| Language | Spanish (later translated into English) |

| Genre | Memoir |

| Publisher | Verso Books |

Publication date | May 17, 1995 |

| Publication place | South America |

| Pages | 166 |

| ISBN | 978-1859849712 |

The Motorcycle Diaries (Spanish: Diarios de motocicleta) is a posthumously published memoir of the Marxist revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara. It traces his early travels, as a 23-year-old medical student, with his friend Alberto Granado, a 29-year-old biochemist. Leaving Buenos Aires, Argentina, in January 1952 on the back of a sputtering single cylinder 1939 Norton 500cc dubbed La Poderosa ("The Mighty One"), they desired to explore the South America they only knew from books.[1] During the formative odyssey Guevara is transformed by witnessing the social injustices of exploited mine workers, persecuted communists, ostracized lepers, and the tattered descendants of a once-great Inca civilization. By journey's end, they had travelled for a "symbolic nine months" by motorcycle, steamship, raft, horse, bus, and hitchhiking, covering more than 8,000 kilometres (5,000 miles) across places such as the Andes, the Atacama Desert, and the Amazon River Basin.

The book has been described as a classic coming-of-age story: a voyage of adventure and self-discovery that is both political and personal.[2] Originally marketed by Verso as "Das Kapital meets Easy Rider",[3] The Motorcycle Diaries has been a New York Times bestseller several times.[4]

Pre-expedition

[edit]

Ernesto Guevara spent long periods traveling around Latin America during his studies of medicine, beginning in 1948, at the University of Buenos Aires. In January 1950, Guevara attempted his first voyage. He traversed 4,500 kilometres (2,800 miles) through the northern provinces of Argentina on a bicycle on which he had installed a small engine. He arrived at San Francisco del Chañar, near Córdoba, where his friend Alberto Granado ran the dispensary of the leper-centre. This experience allowed Guevara to have long conversations with the patients about their disease.

This pre-expedition gave Guevara a taste of what would be experienced in his more extensive South American travels. The journey broke new ground for him in activities that would become central to his life: travelling and writing a diary.[5]: 65 His own father said that it was preparation for his subsequent long journeys across South America.[6]

Guevara relied upon the hospitality of strangers that he encountered, as he and Granado would throughout their later travels. For example, following a puncture, he flagged down a lorry to take him to his next destination.[7]: 63 In another instance, in Loreto, he asked for hospitality from a local police officer when he had nowhere to stay.[7]: 54 The trip encouraged Guevara's style of traveling that would be seen in the Motorcycle Diaries. By the time he reached Jujuy, he had decided that the best way to get to know and to understand a country was by visiting hospitals and meeting the patients that they housed.[7]: 66 He was not interested in the sites for tourists, and preferred meeting the people in custody of the police or the strangers that he met en route with whom he struck up a conversation.[8] Guevara had seen the parallel existence of the poverty and deprivation faced by the native populations.[9] Guevara also noted 'turbulence' in the region under the Río Grande[verification needed], but having not actually crossed this river, Guevara, historian John Lee Anderson argues, used it as a symbol of the United States, and this was an early glimmer of the notion of neocolonial exploitation that would obsess him in later life.[5]: 63 For the young Guevara, the trip had been an education.[7]: 68

It was the success of his Argentinian "raid", as he put it, that awakened in him a desire to explore the world and prompted the commencing of new travel plans.[5]: 65

Upon completion of his bicycle journey, El Gráfico, a sports magazine in Argentina, published a picture of Guevara on his bike. The company that manufactured the engine Ernesto had adapted to his bicycle tried to use it for advertising, claiming it was very strong since Guevara had gone on such a long tour using its power.[10]

While he continued studying, he also worked as a nurse on trading and petroleum ships of the Argentine national shipping-company. This allowed Guevara to travel from the south of Argentina to Brazil, Venezuela and Trinidad.

Expedition

[edit]

This isn't a tale of derring-do, nor is it merely some kind of "cynical account"; it isn't meant to be, at least. It's a chunk of two lives running parallel for a while, with common aspirations and similar dreams. In nine months a man can think a lot of thoughts, from the height of philosophical conjecture to the most abject longing for a bowl of soup – in perfect harmony with the state of his stomach. And if, at the same time, he's a bit of an adventurer, he could have experiences which might interest other people and his random account would read something like this diary.

— Diary introduction

In January 1952, Guevara's older friend, Alberto Granado, a biochemist, and Guevara, decided to take a year off from their medical studies to embark on a trip they had spoken of making for years: traversing South America on a motorcycle, which has metaphorically been compared to carbureted version of Don Quixote's Rocinante.[11] Guevara and the 29-year-old Granado soon set off from Buenos Aires, Argentina, astride a 1939 Norton 500 cc motorcycle they named La Poderosa II ("The Mighty II") with the idea of eventually spending a few weeks volunteering at the San Pablo Leper colony in Peru on the banks of the Amazon River. In total, the journey took Guevara through Argentina, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, and to Miami, before returning home to Buenos Aires.

The trip was carried out in the face of some opposition by Guevara's parents, who knew that their son was both a severe asthmatic and a medical student close to completing his studies. However, Granado, himself a doctor, assuaged their concerns by guaranteeing that Guevara would return to finish his degree (which he ultimately did).[12]

The first stop: Miramar, Argentina, a small resort where Guevara's girlfriend, Chichina, was spending the summer with her upper-class family. Two days stretched into eight, and upon leaving, Chichina gave Guevara a gold bracelet. The two men crossed into Chile on February 14. At one point they introduced themselves as internationally renowned leprosy experts to a local newspaper, which wrote a glowing story about them. The travelers later used the press clipping as a way to score meals and other favors with locals along the way.

We are looking for the bottom part of the town. We talk to many beggars. Our noses inhale attentively the misery.

— Guevara's entry on Valparaíso, Chile

In reference to his experience in Chile, Guevara also writes: "The most important effort that needs to be done is to get rid of the uncomfortable 'Yankee-friend'. It is especially at this moment an immense task, because of the great amount of dollars they have invested here and the convenience of using economical pressure whenever they believe their interests are being threatened."

At night, after the exhausting games of canasta, we would look out over the immense sea, full of white-flecked and green reflections, the two of us leaning side by side on the railing, each of us far away, flying his own aircraft to the stratospheric regions of his own dreams. There we understood that our vocation, our true vocation, was to move for eternity along the roads and seas of the world. Always curious, looking into everything that came before our eyes, sniffing out each corner but only very faintly – not setting down roots in any land or staying long enough to see the substratum of things; the outer limits would suffice.

Guevara, aboard a ship in the Pacific Ocean

Unable to get a boat to Easter Island as they intended, they headed north, where Guevara's political consciousness began to stir as he and Granado moved into mining country.[13] They visited Chuquicamata copper mine, the world's largest open-pit mine and the primary source of Chile's wealth. While getting a tour of the mine he asked how many men died in its creation. At the time it was run by U.S. mining monopolies of Anaconda and Kennecott and thus was viewed by many as a symbol of "imperialist gringo domination".[13] A meeting with a homeless communist couple in search of mining work made a particularly strong impression on Guevara, who wrote: "By the light of the single candle ... the contracted features of the worker gave off a mysterious and tragic air ... the couple, frozen stiff in the desert night, hugging one another, were a live representation of the proletariat of any part of the world."

In reference to the oppression against the Communist party in Chile, which at the time was outlawed, Guevara said: "It's a great pity, that they repress people like this. Apart from whether collectivism, the 'communist vermin', is a danger to decent life, the communism gnawing at his entrails was no more than a natural longing for something better, a protest against persistent hunger transformed into a love for this strange doctrine, whose essence he could never grasp but whose translation, 'bread for the poor', was something he understood and, more importantly, that filled him with hope. Needless to say, workers at Chuquicamata were in a living Hell."[citation needed]

The trip would not have been as useful and beneficial as it was, as a personal experience, if the motorcycle had held out. This gave us a chance to become familiar with the people. We worked, took on jobs to make money and continue traveling. We hauled merchandise, carried sacks, worked as sailors, cops and doctors.

— Alberto Granado, 2004[14]

In Peru, Guevara was impressed by the old Inca civilization, forced to ride in trucks with Indians and animals after The Mighty One broke down. As a result, he began to develop a fraternity with the indigenous campesinos. In March 1952 they both arrived at the Peruvian Tacna. After a discussion about the poverty in the region, Guevara referred in his notes to the words of Cuban poet José Marti: "I want to link my destiny to that of the poor of this world". In May they arrived in Lima, Peru and during this time Guevara met doctor Hugo Pesce, a Peruvian scientist, director of the national leprosy program, and an important local Marxist. They discussed several nights until the early morning and years later Che identified these conversations as being very important for his evolution in attitude towards life and society.

In May, Guevara and Granado left for the leper colony of San Pablo in the Peruvian Amazon Rainforest, arriving there in June. During his stay Guevara complained about the miserable way the people and sick of that region had to live. Guevara also swam once from the side of the Amazon River where the doctors stayed, to the other side of the river where the leper patients lived, a considerable distance of 4 kilometres (2.5 miles). He describes how there were no clothes, almost no food, and no medication. However, Guevara was moved by his time with the lepers, remarking that

All the love and caring just consist on coming to them without gloves and medical attire, shaking their hands as any other neighbor and sitting together for a chat about anything or playing football with them.[15]

After giving consultations and treating patients for a few weeks, Guevara and Granado left aboard the Mambo-Tango raft (shown) for Leticia, Colombia, via the Amazon River.

On July 6, 1952, while visiting Bogotá, Colombia, he wrote a letter to his mother. In the letter he described the conditions under the right-wing government of Conservative Laureano Gómez as the following: "There is more repression of individual freedom here than in any country we've been to, the police patrol the streets carrying rifles and demand your papers every few minutes". He also goes on to describe the atmosphere as "tense" and "suffocating", even hypothesizing that "a revolution may be brewing". Guevara was correct in his prognostication, as a military coup in 1953 would take place, bringing General Gustavo Rojas to power. However, the civil war the country was experiencing never went away; rather, tensions were brewing and were leading to an escalation in various regions in Colombia which led to the Colombian civil war, known as La Violencia.

Later that month, Guevara arrived in Caracas, Venezuela, and from there decided to return to Buenos Aires to finish his studies in medical science. However, prior to his return, he travelled by cargo plane to Miami, where the airplane's technical problems delayed him one month. To survive, he worked as a waiter and washed dishes in a Miami bar.

Although he admitted throughout that as a vagabond traveler he could only see things at surface level, he did attempt to delve beneath the sheen of the places he visited. On one occasion, he went to see a woman dying of tuberculosis, leaving appalled by the failings of the public health system. This experience led him to ruminate the following reflection: "How long this present order, based on the absurd idea of caste, will last is not within my means to answer, but it's time that those who govern spent less time publicizing their own virtues and more money, much more money, funding socially useful works."

It is at times like this, when a doctor is conscious of his complete powerlessness, that he longs for change: a change to prevent the injustice of a system in which only a month ago this poor woman was still earning her living as a waitress, wheezing and panting but facing life with dignity. In circumstances like this, individuals in poor families who can’t pay their way become surrounded by an atmosphere of barely disguised acrimony; they stop being father, mother, sister or brother and become a purely negative factor in the struggle for life and, consequently, a source of bitterness for the healthy members of the community who resent their illness as if it were a personal insult to those who have to support them.

— Guevara while treating a peasant woman dying of tuberculosis

Witnessing the widespread endemic poverty, oppression and disenfranchisement throughout Latin America, and influenced by his readings of Marxist literature, Guevara later decided that the only solution for the region's structural inequalities was armed revolution. His travels and readings throughout this journey also led him to view Latin America not as a group of separate nations, but as a single entity requiring a continent-wide strategy for liberation from what he viewed as imperialist and neo-colonial domination. His conception of a borderless, united, Hispanic-America, sharing a common mestizo bond, was a theme that would prominently recur during his later activities and transformation from Ernesto the traveler into Che Guevara the iconic revolutionary.

Transformation

[edit]

Although it is considered to have been formative, scholars have largely ignored this period of Guevara's life.[16]: 2 However, historians and biographers now agree that the experience had a profound impact on Guevara, who later became one of the most famous guerrilla leaders in history. "His political and social awakening has very much to do with this face-to-face contact with poverty, exploitation, illness, and suffering", said Carlos M. Vilas, a history professor at the Universidad Nacional de Lanús in Buenos Aires, Argentina.[17]

In May 2005, Alberto Granado described their journey to the BBC, stating: "The most important thing was to realise that we had a common sensibility for the things that were wrong and unjust." According to Granado, their time at the leper colony of San Pablo in the Amazon also proved pivotal. Recalling that they shared everything with the sick people and describing Guevara's wave on departure as follows: "I got the impression that Che was saying goodbye to institutional medicine and becoming a doctor of the people".[18] Granado later observed that by the end of their journey, "We were just a pair of vagabonds with knapsacks on our backs, the dust of the road covering us, mere shadows of our old aristocratic egos."[2]

According to his daughter Aleida Guevara in a 2004 article, throughout the book, we can see how Guevara became aware that what poor people needed was not his scientific knowledge as a doctor, but his strength and persistence to bring social change.[19]

Guevara's experience of the South American continent also helped to shape his revolutionary sensibilities. When discussing the plight of the downtrodden Indians of Peru, Granado discussed the formation of an Indian political party to begin a Túpac Amaru Indian Revolution. Guevara allegedly replied, "Revolution without firing a shot? You're crazy?".[20] The journey was also formative in his political beliefs; for example, historian Paulo Drinot notes that the journey stimulated his sentiments of Pan-Americanism that would later shape his revolutionary behaviors.[16]: 8

Scholar Lucía Álvarez De Toledo argues that it was on these motorcycle travels that he "disregarded his social class and his white European racial ancestry" and retained the view of himself as an Argentine, as a member of the United America he had encountered during his travels.[21] Having said this, with the exception of Guatemala, Toledo believed that Guevara showed little concern with the policies of the countries he encountered.[16]: 4 In total however, Guevara's travels in the 1950s played an important role in determining his view on the world "and his later revolutionary trajectory."[16]: 17

Editions

[edit]The book was first published in 1993 as Notas de viaje by Casa Editora Abril in Havana, Cuba. The first English edition was brought out by Verso Books in 1995.

A 2003 edition published by Ocean Press and the Che Guevara Studies Center, Havana, included a preface by Guevara's daughter Aleida Guevara March and an introduction by Cintio Vitier. There had been rumors of a conspiracy to prohibit its publication in Cuba, but the director of Ocean Press denied this, saying that the book had been legally published in Cuba and pointing out that the Union of Young Communists brought out an edition, with another to be published by the Che Guevara Studies Center. Furthermore, he has given an assurance that its publication has the support of many people, including Fidel Castro.[22]

In 2004, Aleida Guevara explained that her father had not intended his diary to be published, and that it consisted of "a sheaf of typewritten pages". But already in the 1980s, his family worked on his unpublished manuscripts.[19]

Review

[edit]Guevara's youthful Motorcycle Diaries is rebellious in ways that are not immediately obvious. This travelogue shows Ernesto the Medical Student developing a sense of Pan-Latin Americanism that fuses the interests of indigenous Andean peasants with traditional adversaries like upper-middle-class Argentine intellectuals (i.e. Guevara). The book ventures a unified regional opposition to U.S. hegemony and global capitalism's sometimes ravaging effects on Latin America.

Further reading

[edit]- Back on the Road: A Journey Through Latin America, by Ernesto "Che" Guevara & Alberto Granado, Grove Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8021-3942-6

- Chasing Che: A Motorcycle Journey in Search of the Guevara Legend, by Patrick Symmes, Vintage, 2000, ISBN 0-375-70265-2

- Che's Chevrolet, Fidel's Oldsmobile: On the Road in Cuba, by Richard Schweid, University of North Carolina Press, 2008, ISBN 0-8078-5887-0

- Che Guevara and the Mountain of Silver: By Bicycle and Train through South America, by Anne Mustoe, Virgin Books, 2008, ISBN 0-7535-1274-2

- Looking for Mr. Guevara: A Journey through South America, by Barbara Brodman, iUniverse, 2001 ISBN 0-595-18069-8

- Roll Over Che Guevara: Travels of a Radical Reporter, by Mark Cooper, Verso, 1996, ISBN 1-85984-065-5

- The Motorcycle Diaries: A Journey Around South America, by Ernesto Che Guevara & translator Ann Wright, Verso, 1996, ISBN 1-85702-399-4

- Traveling with Che Guevara: The Making of a Revolutionary, by Alberto Granado, Newmarket Press, 2004, ISBN 1-55704-639-5

- (Travel Map)—Che's Route: Ernesto Che Guevara Trip Across South America, by de Dios Editores, 2004, ISBN 987-9445-29-5

Film

[edit]- Chasing Che, 2007, developed by National Geographic Adventure, A ten-week series featured on V-me.

- Che, 2008, directed by Steven Soderbergh & starring Benicio del Toro as Che (268 min).

- The Motorcycle Diaries, 2004, directed by Walter Salles, Focus Features, theatrical release (126 min).

- Travelling with Che Guevara, 2004, directed by Gianni Mina, Documentary (110 min).

References

[edit]- ^ On the Trail of the Young Che Guevara by Rachel Dodes, The New York Times, December 19, 2004

- ^ a b Letter from the Americas; Che Today? More Easy Rider Than Revolutionary by Larry Rohter, The New York Times, May 26, 2004

- ^ Doreen Carvajal (30 April 1997). "30 Years After His Death, Che Guevara Has New Charisma". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- ^ NYT bestseller list: No. 38 Paperback Nonfiction on 2005-02-20, No. 9 Nonfiction on 2004-10-07 and on more occasions

- ^ a b c Anderson, John Lee (1997). Che: A Revolutionary Life (First Paperback ed.). New York, New York, USA: Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3558-7.

- ^ Lynch, Ernesto Guevara (2008). De Toledo, Lucía Álvarez (ed.). Young Che: Memories of Che Guevara by his Father (First ed.). New York, New York, USA: Vintage Books. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-307-39044-8.

- ^ a b c d De Toledo, Lucía Álvarez (2010). The Story of Che Guevara (First Canadian ed.). Toronto, Ontario, Canada: HarperCollins Ltd. ISBN 978-1-44340-566-9.

- ^ De Toledo, Lucía Álvarez (2010). The Story of Che Guevara (First Canadian ed.). Toronto, Ontario, Canada: HarperCollins Ltd. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-44340-566-9.

- ^ De Toledo, Lucía Álvarez (2010). The Story of Che Guevara (First Canadian ed.). Toronto, Ontario, Canada: HarperCollins Ltd. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-44340-566-9.

- ^ Hunt, Nigel. "the truth about Che Guevara: Adulthood". www.companeroche.com. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ Easy Revolutionary: Che Guevara Loves and Bikes In Fine 'Motorcycle Diaries' by Joe Morgenstern, The Wall Street Journal, September 24, 2004

- ^ He Rode with Che[permanent dead link] by The Daily Telegraph, March 13, 2011

- ^ a b Che Guevara: Symbol of Struggle, by Tony Saunois, CWI, 2005, ISBN 1-870958-34-9 pg 9

- ^ Biochemist and Che's Motorcycle Companion by The Irish Times, March 12, 2011

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara: 1950-1953

- ^ a b c d Drinot, Paulo (2010). Che's Travels: The Making of a Revolutionary in 1950s Latin America. Durham [NC]: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822391807.

- ^ ""Motorcycle Diaries" Shows Che Guevara at Crossroads". news.nationalgeographic.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2004. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ "My best friend Che". BBC. 9 May 2005. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ a b Aleida Guevara (9 October 2008). "Riding My Father's Motorcycle". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- ^ De Toledo, Lucía Álvarez (2010). The Story of Che Guevara (First Canadian ed.). Toronto, Ontario, Canada: HarperCollins Ltd. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-44340-566-9.

- ^ De Toledo, Lucía Álvarez (2010). The Story of Che Guevara (First Canadian ed.). Toronto, Ontario, Canada: HarperCollins Ltd. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-44340-566-9.

- ^ David Deutschmann; Publisher and President; Ocean Press) (2 June 2008). "Che Guevara's Diaries (letter to the editor". New York Times. Retrieved 8 April 2008.]

- ^ Nine Subversive Travel Books by Thomas Kohnstamm, World Hum, January 12, 2010

External links

[edit]- An Interactive Map of Che Guevara's Motorcycle Diaries

- Book Review ~ The Motorcycle Diaries: A Journey Around South America

- CARE: Che Guevara Trail nominated for Travel Award September 20, 2004

- Guardian: "My Ride with Che", Interview with Alberto Granado February 13, 2004

- LA Times: "Che Guevara's Legacy Looms Larger than Ever in Latin America" October 8, 2007

- New York Times: "On the Motorcycle Behind My Father, Che Guevara" by Aleida Guevara October 12, 2004

- The Motorcycle Diaries: A Journey Around South America - from Motorcycle.com