Manitowoc Shipbuilding Company

44°05′55″N 87°40′03″W / 44.098501°N 87.667438°W

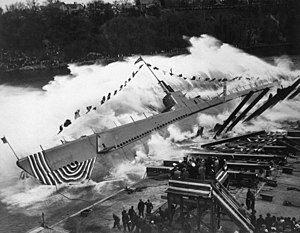

Manitowoc Shipbuilding Company, located in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, was a major shipbuilder for the Great Lakes. It was founded in 1902, with the purchase of the "Burger & Burger Shipyard," a predecessor to The Burger Boat Company, and made mainly steel ferries and ore haulers. During World War II, it built submarines, tank landing craft (LCTs), and self-propelled fuel barges called "YOs".[1] Employment peaked during the military years at 7000. The shipyard closed in 1968, when Manitowoc Company bought Bay Shipbuilding Company and moved their shipbuilding operation to Sturgeon Bay.

Submarine building program

[edit]Shipyard President Charles C. West contacted the Bureau of Construction and Repair in 1939 to propose building destroyers at Manitowoc and transporting them through the Chicago River, Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, Illinois River, and Mississippi River in a floating drydock towed by the tugboat Minnesota. After evaluating the plan and surveying the shipyard, the Navy suggested building submarines instead. A contract for ten submarines was awarded on 9 September 1940. The Navy paid for lift machinery on Chicago's Western Avenue railroad bridge to clear a submarine. The 15-foot-draft submarines entered the floating drydock on the Illinois River to get through the 9-foot-deep Chain of Rocks Channel near the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. Submarines left the drydock at New Orleans and reinstalled periscope shears, periscopes, and radar masts which had been removed to clear bridges over the river.[2]

Manitowoc had never built a submarine before, but the first was completed 228 days before the contract delivery date. Contracts were awarded for additional submarines, and the last submarine was completed by the date scheduled for the 10th submarine of the original contract. Total production of 28 submarines was completed for $5,190,681 less than the contract price.[2][3]

SS-361 through SS-364 were initially ordered as Balao-class, and were assigned hull numbers that fall in the middle of the range of numbers for the Balao class (SS-285 through SS-416 & SS-425–426).[4] Thus, in some references they are listed with that class. However, they were completed by Manitowoc as Gatos, due to an unavoidable delay in Electric Boat's development of Balao-class drawings. Manitowoc was a follow yard to Electric Boat, and was dependent on them for designs and drawings.[5][6]

List of fleet submarines built by Manitowoc

[edit]The following is a complete list of the submarines built by Manitowoc during WW II.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15] Years listed reflect launch dates.

14 of 77 Gato-class:

- 1942 − USS Peto − sank 7 ships in 10 World War II Pacific patrols[16]

- 1942 − USS Pogy − sank 16 ships in 10 World War II Pacific patrols[16]

- 1942 − USS Pompon − sank 3 ships in 9 World War II Pacific patrols[17]

- 1942 − USS Puffer − sank 8 ships in 9 World War II Pacific patrols[18]

- 1942 − USS Rasher − sank 18 ships in 8 World War II Pacific patrols, 2nd highest tonnage sunk by a US submarine during the war[17]

- 1943 − USS Raton − sank 9 ships in 8 World War II Pacific patrols[17]

- 1943 − USS Ray − sank 14 ships in 8 World War II Pacific patrols[16]

- 1943 − USS Redfin − sank 5 ships in 7 World War II Pacific patrols[19]

- 1943 − USS Robalo − 3 World War II Pacific patrols[20]

- 1943 − USS Rock − sank 1 ship in 6 World War II Pacific patrols[21]

- 1943 − USS Golet − 2 World War II Pacific patrols[22]

- 1943 − USS Guavina − sank 5 ships in 6 World War II Pacific patrols[21]

- 1943 − USS Guitarro − sank 6 ships in 5 World War II Pacific patrols[23]

- 1943 − USS Hammerhead − sank 11 ships in 7 World War II Pacific patrols[23]

14 of 120 Balao-class:

- 1943 − USS Hardhead − sank 7 ships in 6 World War II Pacific patrols[18]

- 1944 − USS Hawkbill − sank 6 ships in 5 World War II Pacific patrols[18]

- 1944 − USS Icefish − sank 2 ships in 5 World War II Pacific patrols[18]

- 1944 − USS Jallao − sank 2 ships in 4 World War II Pacific patrols[16]

- 1944 − USS Kete − sank 3 ships in 2 World War II Pacific patrols[24]

- 1944 − USS Kraken − 4 World War II Pacific patrols[18]

- 1944 − USS Lagarto − sank 3 ships in 2 World War II Pacific patrols[23]

- 1944 − USS Lamprey − 3 World War II Pacific patrols[18]

- 1944 − USS Lizardfish − 2 World War II Pacific patrols[23]

- 1944 − USS Loggerhead − 2 World War II Pacific patrols[18]

- 1944 − USS Macabi − 1 World War II Pacific patrol[16]

- 1944 − USS Mapiro

- 1944 − USS Menhaden

- 1945 − USS Mero

Landing Craft Tank LCT

[edit]Manitowoc Shipbuilding built 36 Landing Craft Tank. The model ID was from LCT(5) 1 to LCT(5) 36, LCT were not given ship names. Many were used for the Invasion of Normandy from 6 to 25 June 1944. Of the 36 LCTs built by Manitowoc, 9 sank in action. Landing Craft Tank has a: displacement of 285 tons, length of 114' 2", beam of 32' 8", draft of 3' 6", top speed of 10 kts., a range of 700 nautical miles, held 1 officer and 10 enlisted men, a cargo capacity of 150 short tons, armament of two single 20mm AA guns, and two .50 cal. machine guns. Propulsion was from three Grey Marine 6-71 Diesel engines, driving three propellers with 675 shp. Power was from one 20 kW Diesel engine.[25][26][27]

World War 1

[edit]For World War 1 and post war support, Manitowoc Shipbuilding built cargo ships from 1917 to 1920. The ships were contracted under the United States Shipping Board and classed as Design 1044.[28] The ships were: 2,124 to 2,711 DWT. Most of these ships were named after lakes. The SS Coquina renamed SS Cynthia Olson was sunk by Japanese submarine I-26 on December 7, 1941. Other notable ships: USS Tide (SP-953), SS Alabama, USS Surveyor (1917), USS Stratford (AP-41), SS Indigirka and SS City of Milwaukee. Post World War 1 Manitowoc built: scows, tugboats, barges, a ferry, three patrol boats for the U.S. Coast Guard and the Presidential yacht USS Potomac (AG-25) (1934).

Post World War 2

[edit]After World War 2 Manitowoc continued to build ships, barges and dredges, from 150 to 649 DWT, until the shipyard closed in 1972. In 1947 Manitowoc built a 900-ton floating drydock for Buffalo New York. Notable post war ships: MV Saginaw (1953) and SS Edward L. Ryerson (1960).

See also

[edit]- USS Potomac (AG-25)

- The Manitowoc Company - successor

Notes

[edit]- ^ Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, pp. 252-3, 258, Random House, New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- ^ a b Nelson, William T., RADM USN "1,500 Miles in a Floating Dry Dock" United States Naval Institute Proceedings March 1980 pp. 86-89

- ^ Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, pp. 252-3, Random House, New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- ^ Fleet Submarine index page at Navsource.org

- ^ Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775-1990: Major Combatants. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 271–273. ISBN 0-313-26202-0.

- ^ Friedman, Norman (1995). U.S. Submarines through 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. p. 209. ISBN 1-55750-263-3.

- ^ Silverstone, Paul H. U.S. Warships of World War II Doubleday & Company (1968) p.197

- ^ Fahey, James C. The Ships and Aircraft of the U.S. Fleet (Victory Edition) Ships and Aircraft (1945) p.32

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot History of United States Naval Operations in World War II (Volume 15) Little, Brown & Company (1962) p.58

- ^ Kafka, Roger and Pepperburg, Roy L. Warships of the World Cornell Maritime Press (1946) p.173

- ^ Preston, Antony Jane's Fighting Ships of World War II Random House (1996) p.290

- ^ Silverstone, Paul H. U.S. Warships of World War II Doubleday & Company (1968) p.201

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot History of United States Naval Operations in World War II (Volume 15) Little, Brown & Company (1962) p.59

- ^ Kafka, Roger and Pepperburg, Roy L. Warships of the World Cornell Maritime Press (1946) p.170

- ^ Silverstone, Paul H. U.S. Warships of World War II Doubleday & Company (1968) p.202

- ^ a b c d e Blair, Clay Jr. Silent Victory, volume 2 J.B.Lippincott Company (1975) p.955

- ^ a b c Blair, Clay Jr. Silent Victory, volume 2 J.B.Lippincott Company (1975) p.954

- ^ a b c d e f g Blair, Clay Jr. Silent Victory, volume 2 J.B.Lippincott Company (1975) p.949

- ^ Blair, Clay Jr. Silent Victory, volume 2 J.B.Lippincott Company (1975) p.956

- ^ Blair, Clay Jr. Silent Victory, volume 2 J.B.Lippincott Company (1975) p.923

- ^ a b Blair, Clay Jr. Silent Victory, volume 2 J.B.Lippincott Company (1975) p.947

- ^ Blair, Clay Jr. Silent Victory, volume 2 J.B.Lippincott Company (1975) p.924

- ^ a b c d Blair, Clay Jr. Silent Victory, volume 2 J.B.Lippincott Company (1975) p.948

- ^ Blair, Clay Jr. Silent Victory, volume 2 J.B.Lippincott Company (1975) p.944

- ^ navsource.org Landing Craft Tank, LCT(5)- 3

- ^ navsource.org Landing Craft Tank, LCT(5)- 26

- ^ navsource.org Landing Craft Tank, LCT(5)-25

- ^ McKellar, N.L. (1963). "Steel Shipbuilding under the U. S. Shipping Board, 1917-1921: Part VII" (PDF). The Belgian Shiplover. 93: 232 – via ShipScribe.