The Blue Angel

| The Blue Angel | |

|---|---|

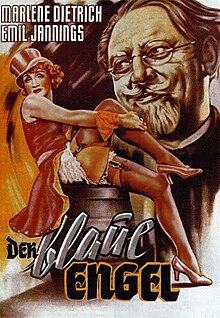

Theatrical release poster | |

| German | Der blaue Engel |

| Directed by | Josef von Sternberg |

| Written by |

|

| Based on | Professor Unrat by Heinrich Mann |

| Produced by | Erich Pommer |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Günther Rittau |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by |

|

| Distributed by | Universum Film A.G. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 108 minutes |

| Country | Germany |

| Languages |

|

| Box office | $77,982 (2001 re-release)[1] |

The Blue Angel (German: Der blaue Engel) is a 1930 German musical comedy-drama film directed by Josef von Sternberg and starring Marlene Dietrich, Emil Jannings and Kurt Gerron. Written by Carl Zuckmayer, Karl Vollmöller and Robert Liebmann, with uncredited contributions by Sternberg, it is based on Heinrich Mann's 1905 novel Professor Unrat (Professor Filth) and set in an unspecified northern German port city.[2] The Blue Angel presents the tragic transformation of a respectable professor into a cabaret clown and his descent into madness. The film was the first feature-length German sound film and brought Dietrich international fame.[3] It also introduced her signature song, Friedrich Hollaender and Robert Liebmann's "Falling in Love Again (Can't Help It)". The film is considered a classic of German cinema.

The film was shot simultaneously in German- and English-language versions. Though the English version was once considered a lost film, a print was discovered in a German film archive, restored and screened at San Francisco's Berlin and Beyond film festival on January 19, 2009.[4] The German version is considered to be "obviously superior";[5] it is longer and not marred by actors struggling with English pronunciation.[6]

Plot

[edit]

Immanuel Rath is a professor at the local Gymnasium (high school for students expected to proceed to university) in Weimar Germany. The boys disrespect and play pranks on him. Rath punishes several of his students for circulating photographs of the beautiful Lola Lola, the headliner at the local cabaret called The Blue Angel. Hoping to catch the boys at the club, Rath goes there later that evening. He does find some students there, but while chasing them, he also finds Lola backstage and becomes infatuated with her. When he returns to the cabaret the following evening to return a pair of panties that was smuggled into his coat by one of his students, he spends the night with her. The next morning, reeling from his night of passion, Rath arrives late to school to find his classroom in chaos; the principal is furious and demands Rath's resignation.

Rath resigns his position at the school and marries Lola. Their happiness is short-lived, however, as Rath becomes humiliatingly dependent on Lola. Over several years, he sinks lower and lower, first selling dirty postcards, and then becoming a clown in Lola's troupe to pay the bills. His growing insecurities about Lola's profession as a "shared woman" eventually consume him with lust and jealousy.

The troupe returns to The Blue Angel, where everyone attends to watch the former professor play a clown. On stage, Rath is humiliated by the magician Kiepert, who breaks eggs on Rath's head, and by seeing Lola embrace and kiss the strongman Mazeppa. Rath is enraged to the point of insanity. He attempts to strangle Lola, but Mazeppa and others subdue him and lock him in a straitjacket.

Later that night, Rath is released and he revisits his old classroom. Rejected, humiliated and destitute, he dies clutching the desk at which he once taught.

Cast

[edit]- Emil Jannings as Professor Immanuel Rath

- Marlene Dietrich as Lola Lola

- Kurt Gerron as Kiepert, the magician

- Rosa Valetti as Guste, the magician's wife

- Hans Albers as Mazeppa, the strongman

- Reinhold Bernt as the clown

- Eduard von Winterstein as the director of school

- Hans Roth as the caretaker of the secondary school

- Rolf Müller as Pupil Angst

- Roland Varno as Pupil Lohmann

- Carl Balhaus as Pupil Ertzum

- Robert Klein-Lörk as Pupil Goldstaub

- Charles Puffy as Innkeeper

- Wilhelm Diegelmann as Captain

- Gerhard Bienert as Policeman

- Ilse Fürstenberg as Rath's maid

- Die Weintraub Syncopators as Orchestra

- Friedrich Hollaender as Pianist

- Wolfgang Staudte as Pupil

Music

[edit]

- "Ich bin von Kopf bis Fuß auf Liebe eingestellt" ("Falling in Love Again (Can't Help It)": Music and lyrics by Friedrich Hollaender, sung by Marlene Dietrich

- "Ich bin die fesche Lola" ("They Call Me Naughty Lola"): Music by Hollaender, lyrics by Robert Liebmann, sung by Dietrich

- "Nimm Dich in Acht vor blonden Frau'n" ("Beware of Blond Women"): Music by Hollaender, lyrics by Richard Rillo, sung by Dietrich

- "Kinder, heut' abend, da such' ich mir was aus" ("A Man, Just a Regular Man"): Music by Hollaender, lyrics by Liebmann,[9] sung by Dietrich

The film also features the famous carillon of the Garrison Church at Potsdam playing "Üb' immer Treu und Redlichkeit" ("Always Be True and Faithful") as well as an orchestral version of the song. The original melody was composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart for Papageno's aria "Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen" from The Magic Flute. In the German Reich and subsequently the Weimar Republic, the lyrics of "Üb' immer Treu und Redlichkeit" symbolized Prussian virtues: "Use always fidelity and honesty / Up to your cold grave / And stray not one inch / From the ways of the Lord".[citation needed]

Background

[edit]By 1929, Sternberg had completed a number of films for Paramount, none of which were box-office successes. However, Paramount's sister studio in Germany, UFA, asked him to direct Emil Jannings in his first sound film. Jannings was the Oscar-winning star of Sternberg's 1928 film The Last Command, and had specially requested Sternberg's participation, despite an "early clash of temperaments" on the set.[10][11][12]

Though The Blue Angel and Morocco, both from 1930, are often cited as his first sound films, Sternberg had already directed "a startling experiment" in asynchronous sound techniques with his 1929 Thunderbolt.[13]

Casting Lola Lola

[edit]Singer Lucie Mannheim was favored by UFA producer Erich Pommer for the part of Lola, with support from leading man Emil Jannings, but Sternberg vetoed her as insufficiently glamorous for a major production. Sternberg also rejected author Heinrich Mann's actress-girlfriend Trude Hesterberg. Brigitte Helm, seriously considered by Sternberg, was not available for the part. Sternberg and Pommer settled on stage and film actress Käthe Haack for the amount of 25,000 Reichsmarks.[14]

Sternberg first saw 29-year-old Marie Magdalene "Marlene" Dietrich at a music revue called the Zwei Krawatten (Two Neckties), which was produced by dramatist Georg Kaiser. Sternberg began immediately to groom Dietrich into "the woman he saw she could become."

Critic Andrew Sarris remarks on the irony of the relationship: "Josef von Sternberg is too often subordinated to the mystique of Marlene Dietrich...the Svengali-Trilby publicity that enshrouded The Blue Angel – and the other six Sternberg-Dietrich film collaborations – obscured the more meaningful merits not only of these particular works but of Sternberg's career as a whole."[15]

Production

[edit]After arriving at Berlin's UFA studios, Sternberg declined an offer to direct a film about Grigori Rasputin, the Russian spiritual advisor to Czar Nicholas II's family. However, he was intrigued with a story by socialist reformer Heinrich Mann entitled Professor Unrat (Professor Filth) (1905), which critiques "the false morality and corrupt values of the German middle class," and agreed to adapt it.[12][16]

The narrative of Mann's story was largely abandoned by Sternberg (with Mann's consent), retaining only scenes describing an affair between a college professor of high rectitude who becomes infatuated with a promiscuous cabaret singer. During filming, Sternberg altered dialogue, added scenes and modified cast characterizations that "gave the script an entirely new dimension."[17][18] The professor's descent from sexual infatuation to jealous rage and insanity was entirely Sternberg's invention.[10][18]

In order to maximize the film's profitability, The Blue Angel was filmed in both German and English, shot in tandem for efficiency. The shooting spanned 11 weeks, from 4 November 1929 to 22 January 1930, at an estimated budget of $500,000—remarkably expensive for an UFA production of that period.[19][20][21]

During filming, although he was still the nominal star of the film (with top billing), Jannings became jealous over the growing closeness between Sternberg and Dietrich and engaged in histrionics and threatened quit the production. The Blue Angel was to be his last great cinematic moment, and it was also one of UFA's last successful films.[22][23] Sarris comments on this double irony:

"The ultimately tragic irony of The Blue Angel is double-edged in a way Sternberg could not have anticipated when he undertook the project. The rise of Lola Lola and fall of Professor Immanuel Rath in reel [sic] life is paralleled in the real life by the rise of Marlene Dietrich and the fall of Emil Jannings..."[10][24]</ref>

Release

[edit]The Blue Angel was scheduled for its Berlin premiere on 1 April 1930, but UFA owner and industrialist Alfred Hugenberg, unhappy with socialist Heinrich Mann's association with the production, blocked release. Production manager Pommer defended the film, and Mann issued a statement distancing his anti-bourgeois critique from Sternberg's more sympathetic portrayal of professor Immanuel Rath in his movie version.[25] Sternberg, who declared himself apolitical, had departed the country in February, shortly after the film was completed, and conflict ensued. Hugenberg ultimately relented on grounds of financial expediency, still convinced that Sternberg had concealed within The Blue Angel "a parody of the German bourgeoisie."[26][27]

The film proved to be "an instant international success."[28][29] Dietrich, at Sternberg's insistence, was brought to Hollywood under contract to Paramount, where the studio would film and release Morocco in 1930 before The Blue Angel would appear in American theatres in 1931.[30]

Themes and analysis

[edit]The Blue Angel, ostensibly a story of the downfall of a respectable middle-age academic at the hands of a pretty young cabaret singer, is Sternberg's "most brutal and least humorous" film of his œuvre.[31][32] The harshness of the narrative "transcends the trivial genre of bourgeois male corrupted by bohemian female" and the complexity of Sternberg's character development rejects "the old stereotype of the seductress" who ruthlessly cuckolds her men.[33]

Sarris outlines Sternberg's "complex interplay" between Lola and the professor:

"The Blue Angel achieved its most electrifying effects through careful grading and construction. When Dietrich sings "Falling in Love Again" for the first time, the delivery is playful, flirtatious, and self-consciously seductive. The final rendition is harsher, colder, and remorseless. The difference in delivery is not related to the old sterotype of the seductress finally showing her true colors, but rather to a psychological development in Dietrich's Lola from mere sensual passivity to a more forceful fatalism about the nature of her desires. Lola's first instinct is to accept the Professor's paternal protection and her last is to affirm her natural instincts, not as coquettish expedients but as the very terms by which she expresses her existence. Thus, as the Professor has been defeated by Lola's beauty, Lola has been ennobled by the Professor's jealousy..."[33]

Biographer John Baxter echoes this the key thematic sequence that reveals "the tragic dignity" of Rath's downfall:

"[T]he tragedy of Immanuel Rath was not that he lost his head over a woman, but that he could not reconcile the loss of power with the acquisition of freedom." When Rath is forced to relinquish "his authority [over] his students, he sinks into alienated apathy…Rath's failure to grasp the chance opened to him…is portrayed in terms of his increasing silence, as he sinks more and more sullenly into the guise of the ridiculous, ironically named clown…In the end, the authoritarian master of language is bereft of articulate speech", finally erupting into a "paraoxysmic cockscrow" when he discovers that he has been cuckolded by Lola.[34]

When Rath, in a jealous rage, enters the room where Lola is making love to the cabaret strongman Mazeppa, Sternberg declines to show Rath, now a madman, at the moment when he is violently subdued by the authorities and placed in a straitjacket. Sternberg rewards the degraded Professor Rath for having "achieved a moment of masculine beauty [by] crowing like a maddened rooster" at Lola's deception: "Sternberg will not cheapen that moment by degrading a man who has been defeated." Sternberg presents "the spectacle of a prudent, prudish man blocked off from all means of displaying his manhood except the most animalistic." The loss of Lola leaves Rath with but one alternative: death.[10][35][36]

Remakes, adaptations and parodies

[edit]- The Blue Angel (1959), director Edward Dmytryk's remake with Curd Jürgens.

- Pousse-Cafe, a 1966 Broadway musical version with music by Duke Ellington. It was unsuccessful and closed after three performances.[37]

- Pinjra (1972), director V. Shantaram's highly successful Marathi/Hindi adaptation with Sandhya and Shreeram Lagoo.[38]

- Lola (1981), director Rainer Werner Fassbinder's loose adaptation of the film and its source novel.

- The Royal Shakespeare Company produced a stage adaptation, written by Pam Gems and directed by Trevor Nunn, that toured the UK from 1991 to 1992.[39]

- In 1998, the Gems adaptation was translated to Japanese. With added songs composed by accordionist Yasuhiro Kobayashi, the Japanese version was staged as a musical starring Kenji Sawada at the Bunkamura in Tokyo.

- A stage adaptation by Romanian playwright Răzvan Mazilu premiered in 2001 at the Odeon Theatre in Bucharest, starring Florin Zamfirescu as the professor and Maia Morgenstern as Lola Lola.

- In April 2010, Playbill announced that David Thompson was writing the book for a musical adaptation of The Blue Angel, with Stew and Heidi Rodewald providing the score and Scott Ellis directing.[40]

- Lola Lola's nightclub act has been parodied on film by Danny Kaye as Fraulein Lilli in On the Double (1961) and by Helmut Berger in Luchino Visconti's The Damned (1969).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b The Blue Angel (1930) at IMDb[better source needed]

- ^ Reimer & Zachau 2005, p. 34.

- ^ Bordwell, David; Thompson, Kristin (2003) [1994]. "The Introduction of Sound". Film History: An Introduction (2nd ed.). New York City: McGraw-Hill. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-07-115141-2.

- ^ Winnert, Derek (3 June 2014). "The Blue Angel [Der blaue Engel] ***** (1930, Marlene Dietrich, Emil Jannings, Kurt Gerron, Rosa Valetti, Hans Albers) – Classic Movie Review 1285". Derek Winnert. Archived from the original on 7 September 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard, ed. (2005). Leonard Maltin's 2005 Movie Guide. Plume. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-452-28592-7.

- ^ Travers, James (2005). "Der Blaue Engel (1930)". Films de France. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015.

- ^ Baxter 1971, p. 19: "...arrived at only after much experiment..."

- ^ Sarris 1966, p. 28.

- ^ "The Blue Angel - Music". TCM.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d Sarris 1966, p. 25.

- ^ Baxter 1971, p. 63.

- ^ a b Weinberg 1967, p. 48.

- ^ Sarris 1998, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Baxter 1971, p. 66.

- ^ Sarris 1998, p. 210.

- ^ Baxter 1971, pp. 63, 66.

- ^ Baxter 1971, p. 72.

- ^ a b Weinberg 1967, p. 50.

- ^ Weinberg 1967, p. 51.

- ^ Baxter 1971, pp. 63, 67, 74–75.

- ^ Sarris 1966, p. 25: "The film was produced simultaneously in German and English language versions for the maximum benefit of the Paramount-Ufa combine in world [movie distribution] markets."

- ^ Baxter 1971, p. 74: The production "was complicated [by the Sternberg/Dietrich] romance...Jannings, as expected, had reacted with special bitterness to the affair, working actively to break down their rapport, throwing tantrums and threatening to walk out."

- ^ Baxter 1971, pp. 63, 74–75: The Blue Angel "had no successors at UFA"

- ^ Sarris 1998, p. 220.

- ^ Weinberg 1967, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Baxter 1971, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Weinberg 1967, p. 54: "Hugenberg [a political reactionary] had sensed that, within the framework of an entertainment film, Sternberg had subtly mirrored the paranoiac tendencies of the Prussian bourgeoisie."

- ^ Baxter 1971, p. 75.

- ^ Weinberg 1967, p. 54.

- ^ Sarris 1998, p. 219.

- ^ Sarris 1998, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Sarris 1998, p. 121: "The Blue Angel (1930) [depicts] the downfall of a middle-aged bourgeois male through the machinations of a disreputable demi-mondaine..."

- ^ a b Sarris 1998, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Baxter 1971, p. 124.

- ^ Sarris 1998, p. 221: "Sternberg's profundity...is measured less by the breadth of this vision than by the perfection of his form and by the emotional force of his characters within that form."

- ^ Sarris 1998, p. 221: "...it is Lola's strength that she has lived with shabbiness long enough to know how to bend without breaking and the Professor's tragic misfortune to bend to first and still break after all."

- ^ Joyce, Mike (18 February 1993). "Ellington's Lesser Gem". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ "The German Connection". Indian Express. 15 January 2006. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ "RSC Performances - The Blue Angel". Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Archived from the original on 24 November 2022. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ Simonson, Robert (1 April 2010). "Scottsboro Librettist David Thompson Working on New Musicals With Stew, Scott Ellis". Playbill. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012.

Sources

[edit]- Baxter, John (1971). The Cinema of Josef von Sternberg. London: A. S. Barnes & Co. ISBN 978-0498079917.

- Black, Gregory D. (1994). Hollywood Censored: Morality Codes, Catholics, and the Movies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45299-1.

- Reimer, Robert C.; Zachau, Reinhard (2005). German Culture Through Film: An Introduction to German Cinema. Newburyport, MA: Focus Publishing. ISBN 978-1585101023.

- Sarris, Andrew (1966). The Films of Josef von Sternberg. New York: Doubleday.

- Sarris, Andrew (1998). "You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet": The American Talking Film: History & Memory, 1927–1949. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195038835.

- Tibbetts, John C.; Welsh, James M., eds. (2005). The Encyclopedia of Novels Into Film (2nd ed.). Checkmark Books. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-1859835203.

- Wakeman, John (1988). World Film Directors: Volume One 1890-1945 (1st ed.). New York: H.W. Wilson. ISBN 978-0824207571.

- Weinberg, Herman G. (1967). Josef von Sternberg: a Critical Study of the Great Film Director. New York: Dutton.

External links

[edit]- The Blue Angel at IMDb

- The Blue Angel at AllMovie

- The Blue Angel at Rotten Tomatoes

- Dissecting The Blue Angel – Danny Hahn

- The Blue Angel at the TCM Movie Database

- Notes on Film: The Blue Angel – Thomas Caldwell

- 1930 films

- 1930 comedy-drama films

- 1930 multilingual films

- 1930 musical comedy films

- 1930s musical comedy-drama films

- Babelsberg Studio films

- 1930s English-language films

- Films about adultery in Germany

- Films about educators

- Films about entertainers

- Films about musical theatre

- Films based on German novels

- Films directed by Josef von Sternberg

- Films of the Weimar Republic

- Films produced by Erich Pommer

- Films scored by Friedrich Hollaender

- Films set in the 1920s

- Films set in cabarets

- Films set in Germany

- German black-and-white films

- 1930s German-language films

- German multilingual films

- German musical comedy-drama films

- Tragicomedy films

- UFA GmbH films

- 1930s German films

- English-language musical comedy-drama films