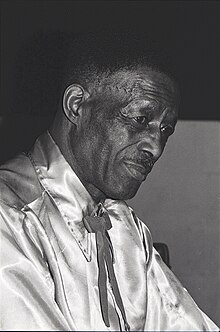

Son House

Son House | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Edward James House Jr. |

| Born | March 21, 1902[a] Lyon, Mississippi, U.S.[b] |

| Died | October 19, 1988 (aged 86) Detroit, Michigan, U.S. |

| Genres | Delta blues |

| Occupation | Musician |

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1930–1943, 1964–1974 |

| Labels | |

Edward James "Son" House Jr. (March 21, 1902[a] – October 19, 1988) was an American Delta blues singer and guitarist, noted for his highly emotional style of singing and slide guitar playing.

After years of hostility to secular music, as a preacher and for a few years also working as a church pastor, he turned to blues performance at the age of 25. He quickly developed a unique style by applying the rhythmic drive, vocal power and emotional intensity of his preaching to the newly learned idiom. In a short career interrupted by a spell in Parchman Farm penitentiary, he developed his musicianship to the point that Charley Patton, the foremost blues artist of the Mississippi Delta region, invited him to share engagements and to accompany him to a 1930 recording session for Paramount Records.

Issued at the start of the Great Depression, the records did not sell and did not lead to national recognition. Locally, House remained popular, and in the 1930s, together with Patton's associate Willie Brown, he was the leading musician of Coahoma County. There he was a formative influence on Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters. In 1941 and 1942, House and the members of his band were recorded by Alan Lomax and John W. Work for the Library of Congress and Fisk University. The following year, he left the Delta for Rochester, New York, and gave up music.

In 1964, Alan Wilson, co-founder of the band Canned Heat, found House and had him listen to his old recordings. He encouraged him to find his way back to the music and from this collaboration, Father of Folk Blues was born. Wilson even played second guitar on “Empire State Express” and the harp on ”Levee Camp Moan”. Son's manager Dick Waterman said,” Al Wilson helped Son House find Son House”. He relearned his repertoire and established a career as an entertainer, performing for young, mostly white audiences in coffeehouses, at folk festivals and on concert tours during the American folk music revival, billed as a "folk blues" singer. He recorded several albums and some informally taped concerts have also been issued as albums.[1] In 2017, his single "Preachin' the Blues" was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame.[2]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]

House was born in the hamlet of Lyon,[b] north of Clarksdale, Mississippi,[3] the second of three brothers, and lived in the rural Mississippi Delta until his parents separated when he was about seven or eight years old. His father, Eddie House Sr., was a musician, playing the tuba in a band with his brothers and sometimes playing the guitar. He was a church member but also a drinker; he left the church for a time as a result of his drinking, but then gave up alcohol and became a Baptist deacon. Young Eddie House adopted the family commitment to religion and churchgoing. He also absorbed the family love of music but confined himself to singing, showing no interest in the family instrumental band, and hostile to the blues on religious grounds.[4]

When House's parents separated, his mother took him to Tallulah, Louisiana, across the Mississippi River from Vicksburg, Mississippi. When he was in his early teens, they moved to Algiers, New Orleans. Recalling these years, he would later speak of his hatred of blues and his passion for churchgoing (he described himself as "churchy" and "churchified"). At fifteen, probably while living in Algiers, he began preaching sermons.[5]

At the age of nineteen, while living in the Delta, he married Carrie Martin, an older woman from New Orleans. This was a significant step for House; he married in church and against family opposition. The couple moved to her hometown of Centerville, Louisiana to help run her father's farm. After a couple of years, feeling used and disillusioned, House recalled, "I left her hanging on the gatepost, with her father tellin' me to come back so we could plow some more." Around the same time, probably 1922, House's mother died. In later years, he was still angry about his marriage and said of Carrie, "She wasn't nothin' but one of them New Orleans whores".[6]

House's resentment of farming extended to the many menial jobs he took as a young adult. He moved frequently, on one occasion taking off to East Saint Louis to work in a steel plant. The one job he enjoyed was on a Louisiana horse ranch, which later he celebrated by wearing a cowboy hat in his performances.[7] He found an escape from manual labor when, following a conversion experience ("getting religion") in his early twenties, he was accepted as a paid pastor, first in the Baptist Church and then in the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church. However, he fell into habits which conflicted with his calling, drinking like his father and probably also womanizing. This led him, after several years of conflict, to leave the church, ceasing his full-time commitment although he continued to preach sermons from time to time.[8]

Blues performer

[edit]In 1927, at the age of 25, House underwent a change of musical perspective as rapid and dramatic as a religious conversion. In a hamlet south of Clarksdale, he heard one of his drinking companions, either James McCoy or Willie Wilson (his recollections differed), playing bottleneck guitar, a style he had never heard before. He immediately changed his attitude about the blues, bought a guitar from a musician called Frank Hoskins and within weeks was playing with Hoskins, McCoy and Wilson. Two songs he learned from McCoy would later be among his best known, "My Black Mama" and "Preachin' the Blues". Another source of inspiration was Rube Lacey,[9] a much better known performer who had recorded for Columbia Records in 1927 (no titles were released) and for Paramount Records in 1928 (two titles were released). In an astonishingly short time, with only these four musicians as models, House developed to a professional standard a blues style based on his religious singing and simple bottleneck guitar style.[10]

Around 1927 or 1928, he had been playing in a juke joint when a man went on a shooting spree, wounding House in the leg, and he allegedly shot the man dead.[11] House received a 15-year sentence at the Mississippi State Penitentiary (Parchman Farm), of which he served two years between 1928 and 1929.[12] He credited his re-examination and release to an appeal by his family, but also spoke of the intervention by the influential white planter for whom they worked.[13] The date of the killing and the duration of his sentence are unclear; House gave different accounts to different interviewers, and searches by his biographer Daniel Beaumont found no details in the court records of Coahoma County or in the archive of the Mississippi Department of Corrections.[14]

Upon his release in 1929 or early 1930, House was strongly advised to leave Clarksdale and stay away.[15] He walked to Jonestown and caught a train to the small town of Lula, Mississippi, sixteen miles north of Clarksdale and eight miles from the blues hub of Helena, Arkansas. Coincidentally, the great star of Delta blues, Charley Patton, was also in virtual exile in Lula,[15] having been expelled from his base on the Dockery Plantation. With his partner Willie Brown, Patton dominated the local market for professional blues performance. Patton watched House busking when he arrived penniless at Lula station, but did not approach him. He observed House's showmanship attracting a crowd to the café and bootleg whiskey business of a woman called Sara Knight. Patton invited House to be a regular musical partner with him and Brown. House formed a liaison with Knight, and both musicians profited from association with her bootlegging activities.[16] The musical partnership is disputed by Patton's biographers Stephen Calt and Gayle Dean Wardlow. They consider that House's musicianship was too limited to play with Patton and Brown, who were also rumoured to be estranged at the time. They also cite one statement by House that he did not play for dances in Lula.[17] Beaumont concluded that House became a friend of Patton's, traveling with him to gigs but playing separately.[18]

Recording

[edit]In 1930, Art Laibly of Paramount Records traveled to Lula to persuade Patton to record several more sides in Grafton, Wisconsin. Along with Patton came House, Brown, and the pianist Louise Johnson, all of whom recorded sides for the label.[15] House recorded nine songs during that session, eight of which were released, but they were commercial failures. He did not record again commercially for 35 years, but he continued to play with Patton and Brown, and with Brown after Patton's death in 1934. During this time, House worked as a tractor driver for various plantations in the Lake Cormorant area.

Alan Lomax recorded House for the Library of Congress in 1941. Willie Brown, the mandolin player Fiddlin' Joe Martin, and the harmonica player Leroy Williams played with House on these recordings. Lomax returned to the area in 1942, where he recorded House once more.

House then faded from the public view, moving to Rochester, New York, in 1943, and working as a railroad porter for the New York Central Railroad and as a chef.[12]

Rediscovery

[edit]

In 1964, after a long search of the Mississippi Delta region by Nick Perls, Dick Waterman and Phil Spiro, House was "rediscovered" in Rochester, New York working at a train station. He had been retired from the music business for many years and was unaware of the 1960s folk blues revival and international enthusiasm for his early recordings.

He subsequently toured extensively in the United States and Europe and recorded for CBS Records. Like Mississippi John Hurt, he was welcomed into the music scene of the 1960s and played at the Newport Folk Festival in 1964, the New York Folk Festival in July 1965,[19] and the October 1967 European tour of the American Folk Festival, along with Skip James and Bukka White.

The young guitarist Alan Wilson (later of Canned Heat) was a fan of House's. The producer John Hammond asked Wilson, who was just 22 years old, to teach "Son House how to play like Son House," because Wilson had such a good knowledge of blues styles. House subsequently recorded the album Father of Folk Blues, later reissued as a 2-CD set Father of Delta Blues: The Complete 1965 Sessions.[20] House performed with Wilson live, as can be heard on "Levee Camp Moan" on the album John the Revelator: The 1970 London Sessions.

House appeared in Seattle on March 19, 1968, arranged by the Seattle Folklore Society. The concert was recorded by Bob West and issued on Acola Records as a CD in 2006.[21] The Arcola CD also included an interview of House recorded on November 15, 1969 in Seattle.[22]

In the summer of 1970, House toured Europe once again, including an appearance at the Montreux Jazz Festival; a recording of his London concerts was released by Liberty Records. He also played at the Two Days of Blues Festival in Toronto in 1974. On an appearance on the TV arts show Camera Three, he was accompanied by the blues guitarist Buddy Guy.

Ill health plagued House in his later years, and in 1974 he retired once again. He later moved to Detroit, Michigan, where he remained until his death from cancer of the larynx. He had been married five times and had two daughters, Beatrice and Sally. He was buried at the Mt. Hazel Cemetery. Members of the Detroit Blues Society raised money through benefit concerts to put a monument on his grave.

Honors

[edit]In 2007, House was honored with a marker on the Mississippi Blues Trail in Tunica, Mississippi.[23]

In 2017, his single "Preachin' the Blues" was inducted in to the Blues Hall of Fame.[2]

Discography

[edit]78-RPM recordings

Recorded May 28, 1930, in Grafton, Wisconsin, for Paramount Records

- "Walking Blues" (unissued and lost until 1985)

- "My Black Mama – Part I"

- "My Black Mama – Part II"

- "Preachin' the Blues – Part I"

- "Preachin' the Blues – Part II"

- "Dry Spell Blues – Part I"

- "Dry Spell Blues – Part II"

- "Clarksdale Moan" (unissued and lost until 2006)

- "Mississippi County Farm Blues" (unissued and lost until 2006)

Recordings for Library of Congress and Fisk University

Recorded August 1941, at Klack's Store, Lake Cormorant, Mississippi. There are some railway noises in the background on some titles, as the store (which had electricity necessary for the recording) was close to a branch line between Lake Cormorant and Robinsonville.

- "Levee Camp Blues", with Willie Brown, Fiddlin' Joe Martin, Leroy Williams

- "Government Fleet Blues", with Brown, Martin, Williams

- "Walking Blues", with Brown, Martin, Williams

- "Shetland Pony Blues", with Brown

- "Fo' Clock Blues", with Brown, Martin

- "Camp Hollers", with Brown, Martin, Williams

- "Delta Blues", with Williams

Recorded July 17, 1942, Robinsonville, Mississippi

- "Special Rider Blues" [test]

- "Special Rider Blues"

- "Low Down Dirty Dog Blues"

- "Depot Blues"

- "Key of Minor" (Interviews: Demonstration of concert guitar tuning)

- "American Defense"

- "Am I Right or Wrong"

- "Walking Blues"

- "County Farm Blues"

- "The Pony Blues"

- "The Jinx Blues (No. 1)"

- "The Jinx Blues (No. 2)"

The music from both sessions and most of the recorded interviews have been reissued on LP and CD.

Singles

- "The Pony Blues" / "The Jinx Blues", Part 1 (1967)

- "Make Me a Pallet on the Floor" (Willie Brown) / "Shetland Pony Blues" (1967)

- "Death Letter" (1985)

Other albums

This list is incomplete. For a complete list, see external links.

- The Complete Library of Congress Sessions (1964), Travelin' Man CD 02

- Blues from the Mississippi Delta, with J. D. Short (1964), Folkways Records

- The Legendary Son House: Father of Folk Blues (1965), Columbia 2417

- In Concert (Oberlin College, 1965), Stack-O-Hits 9004

- Delta Blues (1941–1942), Smithsonian 31028

- Son House & Blind Lemon Jefferson (1926–1941), Biograph 12040

- The Real Delta Blues (1964–1965 recordings), Blue Goose Records 2016

- Son House & the Great Delta Blues Singers, with Willie Brown and others, Document CD 5002

- Son House at Home: Complete 1969, Document 5148

- Son House (Library of Congress), Folk Lyric 9002

- John the Revelator, Liberty 83391

- American Folk Blues Festival '67 (1 cut), Optimism CD 2070

- Son House (1965-1969), Private Record PR 1

- Son House – Vol. 2 (1964–1974), Private Record PR 2 (1987)

- Father of the Delta Blues: The Complete 1965 Sessions, Sony/Legacy CD 48867

- Living Legends (1 cut, 1966), Verve/Folkways 3010

- Real Blues (1 cut, University of Chicago, 1964), Takoma 7081

- John the Revelator: The 1970 London Sessions, Sequel CD 207

- Son House (1964–1970), Document (limited edition of 20 copies)

- Great Bluesmen/Newport, (2 cuts, 1965), Vanguard CD 77/78

- Blues with a Feeling (3 cuts, 1965), Vanguard CD 77005

- Masters of the Country Blues, House and Bukka White, Yazoo Video 500

- Delta Blues and Spirituals (1995)

- In Concert (Live) (1996)

- "Live" at Gaslight Cafe, N.Y.C., January 3, 1965 (2000)

- New York Central Live (2003)

- Delta Blues (1941–1942) (2003), Biograph CD 118

- Classic Blues from Smithsonian Folkways (2003), Smithsonian Folkways 40134

- Classic Blues from Smithsonian Folkways, vol. 2 (2003), Smithsonian Folkways 40148

- The Very Best of Son House: Heroes of the Blues (2003), Shout! Factory 30251

- Proper Introduction to Son House (2004), Proper

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b His date of birth is a matter of some debate. House alleged that he was middle-aged during World War I and that he was 79 in 1965, which would make his date of birth around 1886. However, all legal records give his date of birth as March 21, 1902.

- ^ a b House said that he was born in Lyon. However, according to some accounts, he was born in nearby Riverton, a now-obsolete hamlet which has since been absorbed into the city of Clarksdale.

References

[edit]- ^ Beaumont, Daniel (2011). Preachin' the Blues; The Life and Times of Son House. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539557-0.

- ^ a b "BLUES HALL OF FAME - ABOUT/Inductions - Blues Foundation". Blues.org. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ Beaumont, p. 27.

- ^ Beaumont, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Beaumont, pp. 30–35.

- ^ Beaumont, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Beaumont, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Beaumont, pp. 36–38.

- ^ Robert Palmer (1981). Deep Blues. Penguin Books. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-14-006223-6.

- ^ Beaumont, pp. 39–45.

- ^ Robert Palmer (1981). Deep Blues. Penguin Books. p. 81-2. ISBN 978-0-14-006223-6.

- ^ a b Davis, Francis. The History of the Blues: The Roots, the Music, the People from Charlie Patton to Robert Cray. pp. 106–109.

- ^ Beaumont, p. 49.

- ^ Beaumont, p. 47.

- ^ a b c Robert Palmer (1981). Deep Blues. Penguin Books. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-14-006223-6.

- ^ Beaumont, pp. 49–52.

- ^ Calt, Stephen, and Wardlow, Gayle (1988). King of the Delta Blues: The Life and Music of Charlie Patton. Rock Chapel Press. p. 211. ISBN 0-9618610-0-2.

- ^ Beaumont, p. 54.

- ^ Du Noyer, Paul (2003). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Music. Fulham, London: Flame Tree Publishing. p. 160. ISBN 1-904041-96-5.

- ^ Davis, Rebecca (1998). "Child Is Father to the Man: How Al Wilson Taught Son House to Play Son House". Blues Access 35 (Fall 1998), pp. 40–43 (with photos by Dick Waterman).

- ^ "Arcola Records, music cds, Traditional Jazz Blues, Son House". Arcolarecords.com. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ "KRAB-FM, Seattle - Programs: KRAB has the Blues - King Biscuit Time with Bob West". Krabarchive.com. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ "Son House". Mississippi Blues Trail.

External links

[edit]- Memphis Beale Street Brass Note Submission Biography

- Illustrated Son House discography

- Son House at Find a Grave

- Inaugural (1980) inductee to Blues Hall of Fame (bio by Jim O'Neal)

- Tampa Red and Son House at the Wayback Machine (archived April 11, 2008), History of National Reso-Phonic Guitars, Part 3

- House Discography at Smithsonian Folkways

- Son House at AllMusic (biography by Cub Koda)

- Son House discography at Discogs

- Son House at IMDb

- Studs Terkel interview of Son House Broadcast on Terkel's radio show on April 19, 1965

- Bob West interview of Son House March 16, 1968

- Delta blues musicians

- Country blues musicians

- Blues revival musicians

- Gospel blues musicians

- Country blues singers

- American blues guitarists

- American male guitarists

- Blues musicians from Mississippi

- Resonator guitarists

- Juke Joint blues musicians

- American slide guitarists

- Columbia Records artists

- 1902 births

- 1988 deaths

- 20th-century American criminals

- People from Coahoma County, Mississippi

- Deaths from cancer in Michigan

- Paramount Records artists

- 20th-century American guitarists

- Guitarists from Mississippi

- People from Lula, Mississippi

- American male criminals

- Mississippi Blues Trail

- African-American guitarists

- 20th-century African-American male singers

- 20th-century American male singers

- 20th-century American singers