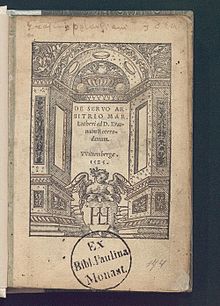

On the Bondage of the Will

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

| |

| Author | Martin Luther |

|---|---|

| Original title | De Servo Arbitrio |

| Translator | Henry Cole; first translation |

| Language | Latin |

| Genre | Philosophy, Theology |

Publication date | December 1525 |

Published in English | 1823; first translation |

| Preceded by | De Libero Arbitrio |

| Followed by | Hyperaspistes |

On the Bondage of the Will (Latin: De Servo Arbitrio, literally, "On Un-free Will", or "Concerning Bound Choice", or "The Enslaved Will") by Martin Luther argued that people can achieve salvation or redemption only through God, and could not choose between good and evil through their own willpower. It was published in December 1525. It was his reply to Desiderius Erasmus' De libero arbitrio diatribe sive collatio or On Free Will, which had appeared in September 1524 as Erasmus' first public attack on some of Luther's ideas.

The debate between Erasmus and Luther is one of the earliest of the Reformation over the issue of free will and predestination, between synergism and monergism, as well as on scriptural authority and human assertion.

Erasmus' Arguments

[edit]Despite his own criticisms of contemporary Roman Catholicism, Erasmus argued that it needed reformation from within and that Luther had gone too far. He held that all humans possessed free will and that the doctrine of predestination conflicted with the teachings and thrust[1] of the Bible, which continually calls wayward humans to repent.[2]

Erasmus argued against the belief that God's foreknowledge of events caused those events, and he held that the doctrines of repentance, baptism, and conversion depended on the existence of free will. He likewise contended that divine grace first called, led, and assisted humans in coming to the knowledge of God, and then supported them as they then used their free will to make choices between good and evil, and enabled them to act on their choices for repentance and good, which in turn could lead to salvation through the atonement of Jesus Christ (Synergism).

His book also denied the authority Luther asserted for Luther's own opinions on matters where Scripture was, in Erasmus' view, unclear: in such situations we should, in public for unity, assent to any teaching of the church, or be non-dogmatic and tolerant otherwise. For Erasmus, one of Luther's flaws as a theologian was his exaggeration:[3]: 106 he imposed meaning on passages that did not support it.[5]

Luther's response

[edit]Luther's response was to claim that original sin incapacitates human beings from working out their own salvation, and that they are completely incapable of bringing themselves to God. As such, there is no free will for humanity, as far as salvation is concerned, because any will they might have is overwhelmed by the influence of sin.[6]

"If Satan rides, it (the will) goes where Satan wills. If God rides, it goes where God wills. In either case there is no ‘free choice'.

— Martin Luther, On the Bondage of the Will[7]: 281

Luther concluded that unredeemed human beings are dominated by obstructions; Satan, as the prince of the mortal world, never lets go of what he considers his own unless he is overpowered by a stronger power, i.e. God. When God redeems a person, he redeems the entire person, including the will, which then is liberated to serve God.

No-one can achieve salvation or redemption through their own willpower—people do not choose between good or evil, because they are naturally dominated by evil, and salvation is simply the product of God unilaterally changing a person's heart and turning them to good ends. Were it not so, Luther contended, God would not be omnipotent and omniscient[citation needed] and would lack total sovereignty over creation.

He also held that arguing otherwise was insulting to the glory of God. As such, Luther concluded that Erasmus was not actually a Christian.[8]

On the Bondage of the Will has been called "a brutally hostile book […] accusing him [Erasmus] of being a hypocrite and an atheist."[3] Several writers express concern that Luther went too far, in expression at least. For Protestant historian Philip Schaff "It is one of his most vigorous and profound books, full of grand ideas and shocking exaggerations, that border on Manichaeism and fatalism."[9] "From beginning to end his work, for all its positive features, is a torrent of invective."[10]: 6 Some historians have said that "the spread of Lutheranism was checked by Luther’s antagonizing (of) Erasmus and the humanists."[11]: 7

Judgements on whether Erasmus or Luther made the better case are usually divided on sectarian lines, and rarely examine Erasmus' follow-up Hyperaspistes. Philosopher John Smith claims "Despite the force of Luther’s arguments, in many ways Erasmus carried the day by laying the foundation for historico-philological biblical criticism—and so Luther’s warnings, as some religious figures and communities stress to this day, were all too accurate, since Erasmus’s Humanism did set the ball rolling down a problematic slippery slope toward nonbelief."[12]: 24

Erasmus' rebuttal

[edit]In early 1526, Erasmus replied to this work with the first part of his two-volume Hyperaspistes ("defender" or "shieldbearer"), followed 18 months later by the 570-page volume II: a very detailed work with a repetitive paragraph-by-paragraph rebuttal of On the Bondage of the Will. Luther did not answer Hyperaspistes, and it never gained widespread scholarly engagement or popular recognition, not even being translated into English for almost 500 years.[13]

Erasmus satirized what he saw as Luther's method of repetitively asserting that tenuous scriptural phrases prove his position, by illustrating how he thought Luther would explain the Lord's Prayer:

" 'Our Father.' Do you hear? Sons are under the authority of their fathers and not vice versa. There is thus no freedom of the will.

'Which art in heaven.' Listen: heaven works on what is below it, not vice versa. Thus our will does not act but is purely passive.

'Hallowed be thy name.' What can be clearer? If the will were free, the honor would belong to man and not to God"; (and so on.)— Erasmus, Hyperaspistes II[13]: 8

Luther's later views on his writings

[edit]Luther was proud of his On the Bondage of the Will, so much so that in a letter to Wolfgang Capito written on 9 July 1537, he said:

Regarding [the plan] to collect my writings in volumes, I am quite cool and not at all eager about it because, roused by a Saturnian hunger, I would rather see them all devoured. For I acknowledge none of them to be really a book of mine, except perhaps the one On the Bound Will and the Catechism.[14]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "They also disagreed on the interpretation of Scripture. Gerhard O. Forde represents Erasmus’ method as a “box score” method, whereas Luther might rely on just “one passage” to convince of truth. Erasmus also held the view that Scripture should be interpreted carefully by trained scholars, whereas Luther thought the Bible should interpret itself and that everyone should read it for themselves." See 'Peckham' p. 276.

- ^ Rupp and Watson (January 1969). Luther and Erasmus: Freewill and Salvation. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-24158-1. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ a b Kimmerle, Heinz (8 April 2024). "The Arguments of Erasmus in His Debate with Luther about Free Will". Scriptura, Geist, Wirkung: 97–108. doi:10.1515/9783111315348-006.

- ^ Shernezian, Very Rev Fr Barouyr (1 January 2022). Erasmus' On Free Will: Conceptual Perspectives From History and Spirituality.

- ^ "Furthermore, Luther’s exegetical method of taking a word from the Holy Scriptures and making it general in every aspect is disagreeable for Erasmus. For instance, Erasmus notes how Luther quotes from Isaias 40:68, “All flesh is grass…” indicating that all human beings are incapable and fallen, which devalues the works of those who served God and his glory. Erasmus answers: “If someone wants to contend that even the most distinguished human quality is nothing but flesh, i.e. a godless disposition, it would be easy to agree, except that he first proves this assertion from Scripture.”"[4]: 18

- ^ "What is above us is no concern of ours." This proverbial statement from De servo arbitrio epitomizes how Luther dissociates himself from scholastic speculations on God’s metaphysical being. According to Luther, sin fundamentally limits human cognition of God and causes humans to experience God as Deus absconditus; an incomprehensible and terrifying presence inducing human suffering. In opposition to natural theology, Luther maintains that God’s goodness is only recognizable in the weakness of the crucified Christ suffering pro nobis. Thus, according to Luther, God reveals himself to sinners wearing a Janus face of both wrathful law and loving mercy. Consequently, believers should be "seeking refuge in God against God." p.659 Stopa, Sasja Emilie Mathiasen (1 November 2018). ""Seeking Refuge in God against God": The Hidden God in Lutheran Theology and the Postmodern Weakening of God". Open Theology. 4 (1): 658–674. doi:10.1515/opth-2018-0049.

- ^ Pekham, John (2007). "An Investigation of Luther's View of the Bondage of the Will with Implications for Soteriology and Theodicy". Journal of the Adventist Theological Society. 18 (2). Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ^ Free will was "a subject that in Erasmus' opinion ought not to provoke many violent emotions.…(Luther's response was) the antitype of Erasmus' work, the most impassioned book he had ever written, a detailed and vehement onslaught on the man whom he saw as an enemy of the Christian faith."Augustijn, Cornelis (2001). "Twentieth-Annual Birthday Lecture". Erasmus of Rotterdam Society Yearbook. 21 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1163/187492701X00038.

- ^ Schaff, Philip. History of the Christian Church, Volume VII. ch 73. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ "(Luther says) The Diatribe (On Free Will) sleeps, snores, is drunk, does not know what it is saying, etc. Its author is an atheist, Lucian himself, a Proteus, etc.Augustijn, Cornelis (2001). "Twentieth-Annual Birthday Lecture: Erasmus as Apologist: The Hyperaspistes II". Erasmus of Rotterdam Society Yearbook. 21 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1163/187492701X00038.

- ^ Eckert, Otto J. (1955). Luther and the Reformation (PDF). Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ Smith, John H. (15 October 2011). Dialogues between Faith and Reason: The Death and Return of God in Modern German Thought. doi:10.7591/9780801463273. ISBN 9780801463273.

- ^ a b Augustijn, Cornelis (2001). "Twentieth-Annual Birthday Lecture: Erasmus as Apologist: The Hyperaspistes II". Erasmus of Rotterdam Society Yearbook. 21 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1163/187492701X00038.

- ^ LW 50:172-173. Luther compares himself to Saturn, a figure from Ancient Greek mythology who devoured most of his children. Luther wanted to get rid of many of his writings except for the two mentioned.

English translations

[edit]- Luther, Martin; Cole, Henry (1823). Martin Luther on the Bondage of the Will: Written in Answer to the Diatribe of Erasmus on Free-will. London: Printed by T. Bensley for W. Simpkin and R . Marshall.

- Luther, Martin. The Bondage of the Will: A New Translation of De Servo Arbitrio (1525), Martin Luther's Reply to Erasmus of Rotterdam. J.I. Packer and O. R. Johnston, trans. Old Tappan, New Jersey: Fleming H. Revell Co., 1957.

- Erasmus, Desiderius and Martin Luther. Luther and Erasmus: Free Will and Salvation. The Library of Christian Classics: Ichthus Edition. Rupp, E. Gordon; Marlow, A.N.; Watson, Philip S.; and Drewery, B. trans. and eds. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1969. (This volume provides an English translation of both Erasmus' De Libero Arbitrio and Luther's De Servo Arbitrio.)

- Career of the Reformer III. Luther's Works, Vol. 33 of 55. Watson, Philip S. and Benjamin Drewery, trans. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1972.

External links

[edit]- Bondage of the Will, by Martin Luther, translated by Henry Cole, London, March, 1823.

The Bondage of the Will public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Bondage of the Will public domain audiobook at LibriVox