David Sassoon & Co.

David Sassoon & Co., Ltd. (in the early years called ″David Sassoon & Sons″) was a trading company operating in the 19th century and early 20th century predominantly in India, China and Japan.

History

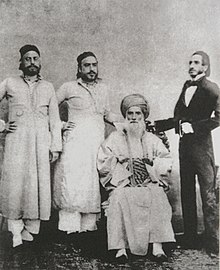

[edit]Established 1832 in Bombay (today Mumbai) by David Sassoon (1792–1864), a Baghdadi Jewish businessman in Bombay. The company was set up in a small counting house at 9 Tamarind Street (does not exist any longer) initially involved in banking activities and property investments.[1] But it soon started to deal successfully in all sorts of commodities like precious metals, silks, gums, spices, wool and wheat. But by that time it specialised in trading Indian cotton yarn and opium from Bombay to China. The latter was promoted by the First Opium War and the Treaty of Nanking in 1842 between the United Kingdom and the Chinese Qing dynasty.[2] For the fast transport of the opium David Sassoon & Co. ran its own so called ″opium clippers".[3]

As David Sassoon & Co. expanded it set up branches in India (Calcutta, Karatchi), in Hongkong (est. 1843), in China (Canton, Hankow, Shanghai (est. 1845)), in Japan (Kobe, Nagasaki, Yokohama), in the Persian Gulf (Bagdad) and in the United Kingdom (London, Manchester).

Like the Rothschilds in Europe David Sassoon placed his many sons as heads of newly established branches of his company.[2] But he remained the sole owner of the business until 1852, when his son Abdallah Sassoon (1818–1896) joined him as a partner, followed by his second son Elias David Sassoon (1820–1880) shortly afterwards.[4]

During the 1860s David Sassoon & Co. started to dominate the opium trade between India and China. By purchasing unharvested crop directly from Indian producers it was able to undercut British competitors which had obtained supplies from middlemen. Dent & Co., which had formerly dominated the Indian-Chinese opium trade, went bankrupt in 1867, while Jardine Matheson ceased to be an important opium dealer either in India or China by the early 1870s.[5] By then David Sassoon & Co. handled around 70% of the trading volume in Indian opium. Jardine Matheson ended its opium trade in 1872, when its last remaining major client, ″Rustomjee Eduljee″ in Bombay, closed.[6]

In 1867, three years after the death of the company's founder, his second son, Elias David Sassoon, broke away from his family's company because of personal resentments between him and his other brothers. He set up his own firm, called "E.D. Sassoon & Co.", starting to trade in dried fruits, nankeen, metals, tea, silk, spices and camphor from modest offices in Bombay and Shanghai.[7] It soon proved to be more energetic than David Sassoon & Co. and by the later Edwardian years its capital was two to three times as much (£1.25m to £1.5m) as the nominal capital of David Sassoon & Co. (£0.5m).[8]

But David Sassoon & Co. did also develop further. In 1872 it moved its head office from Bombay to London (12, Leadenhall Street) for a better access to the markets for capital and information.[9] In 1874 David Sassoon established a new subsidiary in Bombay, the "Sassoon Spinning and Weaving Company", which by the time opened seven cotton mills there.[10][6] In 1875, the David Sassoon & Co. built the Sassoon Docks, the first commercial wet docks in Bombay which helped establishing the international trade with Indian Cotton. In 1883 the company moved into the silk manufacturing business when it founded the ″Sassoon & Alliance Silk Mill Co. Ltd.″. The firm also acquired extensive property in Hong Kong,[11] Canton and northern China.[3] David Sassoon & Co. als acted as agent for many other companies in East Asia and South East Asia,[12] for example in Hong Kong for the ″Norwich Union Fire Insurance Society Ltd.″, both in fire and marine insurance, for the ″Lancashire Insurance Company° (today part of the ″RSA Insurance Group″).[3] and for the Apcar Line, a company which operated steamers plying between Calcutta–Hong Kong and Japan–Shanghai.[citation needed]

Although David Sassoon & Co. stuck with its trading heritage[13] it was involved in banking activities from its earliest years.[14] David Sassoon & Co. formed part of a consortium of British merchants who founded the "Hong Kong & Shanghai Banking Corporation" in 1865 and was also instrumental in setting up in 1873 the "Anglo-California Bank, Ltd." (Later bought by the "Wells Fargo Bank)".[15] When the Imperial Bank of Persia was established in 1889 it was principally funded by David Sassoon & Co., Glyn, Mills & Co., and J. Henry Schröder & Co.[16]

David Sassoon's son Sir Albert Sassoon, Bart. succeeded his father and subsequently passed the business on to Sir Edward Sassoon, Bart., M.P.[11] Under Sir Edward Sassoon's leadership David Sassoon & Co. was in 1901 incorporated as a Joint-stock company[17] with a capital of £500,000. There was no public issue, but for the first time shares were given to leading company managers who did not belong to the Sassoon family. The reorganization was made necessary by intensified completion in both India and China, and above all the growing challenges from Japanese manufactures.[18]

In 1907 the United Kingdom signed a treaty agreeing to gradually eliminate the opium exports to China over the next decade while China agreed to eliminate domestic production over that period. Following this treaty David Sassoon & Co. retreated from the opium trade, eventually stopping it completely, although this had been one of its principal business interests for a long time.[3]

Upon Sir Edward Sassoon's death in 1912 his uncle Frederick David Sassoon (1853–1917), the youngest son of David Sassoon, was the dominant person in the company. After Frederick Sassoon's death 1917 David Gubbay (1865–1928), a cousin, became chairman until his own death in 1926.[19] With Gubbay ended the direct involvement of the Sassoon family in the management of David Sassoon & Co.. Sir Philip Sassoon's (1888–1939) participation in the management of the company as chairman was only nominal although he held on holding shares in it.[20]

After the Second World War David Sassoon & Co. was "a shadow of the firm it had been at the turn of the caentury". In 1982 David Sassoon & Co. was sold for around £2 million to the London stockbroker Rowe Rudd. Although now fully controlled by Rowe Rudd, David Sassoon & Co continued to operate independently from an office in Haymarket in London's West End.[21]

Eventually David Sassoon & Co was sold to UBS of Switzerland. The firms' assets in Asia were later sold by UBS to Sassoon & Co an investment house founded by David Sassoon's younger brother Joseph Sassoon (1795-1872),[22] Today J. Sassoon Financial Group LLC is the holding arm of the Sassoon Family Continuation Trust which holds and manages the assets of the Joseph Sassoon branch of the family, and Sassoon & Co is its investment and merchant banking arm, providing investment management, merchant banking and global advisory services to its clients. The firm invests in composite material technology, agriculture and food security, logistics, energy, mining and technology and financial services in the Eastern and Southern Mediterranean, South America, Asia and Africa. However, the firm maintains a strong focus on the U.S. and Israeli markets, which represent 60% of its portfolio assets.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Peter Stansky: ″Sassoon - The worlds of Philip and Sybil″, Yale University Press, New Haven/ London 2003, p. 5; ISBN 0-300-09547-3

- ^ a b Jonathan Goldstein (Editor): "The Jews of China", Volume One, M.E. Sharpe Publisher, Armonk/ London 1999, p.145, ISBN 0-7656-0103-6

- ^ a b c d David Faure (Editor): "Society - A Documentary History of Hong Kong", Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong 1997, p.125, ISBN 962-209-393-0

- ^ Stanley Jackson: ″The Sassoons - Portrait of a Dynasty″, Second Edition, William Heinemann Ltd., London 1989, pp.19 and 30, ISBN 0-434-37056-8

- ^ Geoffrey Jones: ″Merchants to Multinationals - British Trading Companies in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries″, Oxford University PressOxford 2007, p.41, ISBN 978-0-19-829450-4

- ^ a b Madhavi Thampi: "India and China in the Colonial World", Social Science Press, London/ New York 2017, p.40; ISBN 978-1-138-10269-9

- ^ Stanley Jackson: ″The Sassoons - Portrait of a Dynasty″, Second Edition, William Heinemann Ltd., London 1989, p.48 and 51, ISBN 0-434-37056-8

- ^ Stanley Chapman: The Rise of Merchant Banking, Routledge, London/ New York 2006, p.131, ISBN 978-0-415-48948-5

- ^ Geoffrey Jones: ″Merchants to Multinationals - British Trading Companies in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries″, Oxford University PressOxford 2007, p.51, ISBN 978-0-19-829450-4

- ^ Vijay K. Seth: "Ascent and Decline of native and colonial Trading - Tale of Four Indian Cities", SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd., New Delhi 2019, p.50, ISBN 978-93-532-8085-7

- ^ a b Wright, Arnold (1908). Twentieth Century Impressions of Hong-Kong, Shanghai, and other Treaty Ports of China. London: Lloyd's Greater Britain Pub. Co. p. 224.

- ^ "The Directory & Chronicle for China, Japan, Korea, Indo-China, Straits, Settlements, Malay States, Siam, Netherlands India, Borneo, The Philippines & C. for the Year 1912", The Hongkong Daily Press Office, Hongkong/ London 1912.

- ^ Stanley Jackson: ″The Sassoons - Portrait of a Dynasty″, Second Edition, William Heinemann Ltd., London 1989, p.140, ISBN 0-434-37056-8

- ^ Stanley Chapman: "The Rise of Merchant Banking", Routledge, London/ New York 2006, p.132, ISBN 978-0-415-48948-5

- ^ Stanley Chapman: "The Rise of Merchant Banking", Routledge, London/ New York 2006, p.135, ISBN 978-0-415-48948-5

- ^ Kienholz, M. (2008). Opium Traders and Their Worlds-Volume Two: A Revisionist Exposé of the World's Greatest Opium Traders. iUniverse. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-595-61326-7.

- ^ Paul H. Emden: "Money Powers of Europe in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries", D. Appleton-Century Company, New York 1938, S. 381.

- ^ Stanley Jackson: ″The Sassoons - Portrait of a Dynasty″, Second Edition, William Heinemann Ltd., London 1989, p.119, ISBN 0-434-37056-8

- ^ Peter Stansky: ″Sassoon - The worlds of Philip and Sybil″, Yale University Press, New Haven/ London 2003, p.19-21, ISBN 0-300-09547-3

- ^ Stanley Jackson: ″The Sassoons - Portrait of a Dynasty″, Second Edition, William Heinemann Ltd., London 1989, p.219, ISBN 0-434-37056-8

- ^ Joseph Sassoon: The Sassoons - The Great Global Merchants an the Making of an Empire, Pantheon Books, New York 2022, p. 286

- ^ "The Worlds most powerful and exclusice fortunes" by Al Jazeera in 16.12.2017

- Sassoon family

- Companies established in 1832

- 1832 establishments in the British Empire

- Indian companies established in 1832

- Trading companies of Hong Kong

- Trading companies of the United Kingdom

- British Hong Kong

- History of Hong Kong

- History of foreign trade in China

- Jewish Chinese history

- Opium Wars

- Trading companies