Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

The CND symbol, designed by Gerald Holtom in 1958. It has become a nearly universal peace symbol used in many different versions worldwide.[1] | |

| Abbreviation | CND |

|---|---|

| Formation | November 1957 |

| Location | |

Region served | United Kingdom |

General Secretary | Kate Hudson |

Chair | Tom Unterrainer |

Vice-Chair | Sophie Bolt Ellie Kinney Daniel Blaney |

Vice-President | Caroline Lucas Paul Oestreicher Jeremy Corbyn Alice Mahon Rebecca Johnson Ian Fairlie John Cox Pat Arrowsmith[2] |

| Website | cnduk |

| Anti-nuclear movement |

|---|

|

| By country |

| Lists |

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) is an organisation that advocates unilateral nuclear disarmament by the United Kingdom, international nuclear disarmament and tighter international arms regulation through agreements such as the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. It opposes military action that may result in the use of nuclear, chemical or biological weapons, and the building of nuclear power stations in the UK.

CND began in November 1957 when a committee was formed, including Canon John Collins as chairman, Bertrand Russell as president and Peggy Duff as organising secretary. The committee organised CND's first public meeting at Methodist Central Hall, Westminster, on 17 February 1958. Since then, CND has periodically been at the forefront of the peace movement in the UK. It claims to be Europe's largest single-issue peace campaign. Between 1958 and 1965 it organised the Aldermaston March, which was held over the Easter weekend from the Atomic Weapons Establishment near Aldermaston to Trafalgar Square, London.

Campaigns

[edit]CND's current strategic objectives are:

- The elimination of British nuclear weapons and global abolition of nuclear weapons. It campaigns for the cancellation of the Trident programme by the British government and against the deployment of nuclear weapons in Britain.

- The abolition of weapons of mass destruction, in particular chemical and biological weapons. CND also wants a ban on the manufacture, testing and use of depleted uranium weapons.

- A nuclear-free, less militarised and more secure Europe. It supports the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). It opposes US military bases and nuclear weapons in Europe and British membership of NATO.

- The closure of the nuclear power industry.[3]

In recent years CND has extended its campaigns to include opposition to US and British policy in the Middle East, rather as it broadened its anti-nuclear campaigns in the 1960s to include opposition to the Vietnam War. In collaboration with the Stop the War Coalition and the Muslim Association of Britain, CND has organised anti-war marches under the slogan "Don't Attack Iraq", including protests on 28 September 2002 and 15 February 2003. It also organised a vigil for the victims of the 2005 London bombings.

CND campaigns against the Trident missile. In March 2007 it organised a rally in Parliament Square to coincide with the Commons motion to renew the weapons system. The rally was attended by over 1,000 people. It was addressed by Labour MPs Jon Trickett, Emily Thornberry, John McDonnell, Michael Meacher, Diane Abbott and Jeremy Corbyn who voted against the renewal of Trident, and Elfyn Llwyd of Plaid Cymru and Angus MacNeil of the Scottish National Party. In the House of Commons, 161 MPs (88 of them Labour) voted against the renewal of Trident and the Government motion was carried only with the support of Conservatives.[4]

In 2006 CND launched a campaign against nuclear power. Its membership, which had fallen to 32,000 from a peak of 110,000 in 1983, increased threefold after Prime Minister Tony Blair made a commitment to nuclear energy.[5]

Structure

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2015) |

CND is based in London and has national groups in Wales, Ireland and Scotland, regional groups in Cambridgeshire, Cumbria, the East Midlands, Kent, London, Manchester, Merseyside, Mid Somerset, Norwich, South Cheshire and North Staffordshire, Southern England, South West England, Suffolk, Surrey, Sussex, Tyne and Wear, the West Midlands and Yorkshire, and local branches.

There are five "specialist sections": Trade Union CND, Christian CND, Labour CND, Green CND and Ex-Services CND,[6] which have rights of representation on the governing council. There are also parliamentary, youth and student groups.

History

[edit]The First Wave: 1957–1963

[edit]

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament was founded in 1957 in the wake of widespread fear of nuclear conflict and the effects of nuclear tests. In the early 1950s Britain had become the third atomic power, after the US and the USSR and had recently tested an H-bomb.[7]

In November 1957, J. B. Priestley wrote an article for the New Statesman magazine, "Britain and the Nuclear Bombs",[8][9][10] advocating unilateral nuclear disarmament by Britain. In it he said:

In plain words: now that Britain has told the world she has the H-bomb she should announce as early as possible that she has done with it, that she proposes to reject, in all circumstances, nuclear warfare.

The article prompted many letters of support and at the end of the month the editor of the New Statesman, Kingsley Martin, chaired a meeting in the rooms of Canon John Collins in Amen Court to launch the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Collins was chosen as its chairman, Bertrand Russell as its president and Peggy Duff as its organising secretary. The other members of its executive committee were Martin, Priestley, Ritchie Calder, journalist James Cameron, Howard Davies, Michael Foot, Arthur Goss, and Joseph Rotblat. The Campaign was launched at a public meeting at Central Hall, Westminster, on 17 February 1958, chaired by Collins and addressed by Michael Foot, Stephen King-Hall, J. B. Priestley, Bertrand Russell and A. J. P. Taylor.[11] It was attended by 5,000 people, a few hundred of whom demonstrated at Downing Street after the event.[12][13]

The new organisation attracted considerable public interest and drew support from a range of interests, including scientists, religious leaders, academics, journalists, writers, actors and musicians. Its sponsors included John Arlott, Peggy Ashcroft, the Bishop of Birmingham Dr J. L. Wilson, Benjamin Britten, Viscount Chaplin, Michael de la Bédoyère, Bob Edwards, MP, Dame Edith Evans, A.S.Frere, Gerald Gardiner, QC, Victor Gollancz, Dr I. Grunfeld, E. M. Forster, Barbara Hepworth, Patrick Heron, Rev. Trevor Huddleston, Sir Julian Huxley, Edward Hyams, the Bishop of Llandaff Dr Glyn Simon, Doris Lessing, Sir Compton Mackenzie, the Very Rev George McLeod, Miles Malleson, Denis Matthews, Sir Francis Meynell, Henry Moore, John Napper, Ben Nicholson, Sir Herbert Read, Flora Robson, Michael Tippett, the cartoonist 'Vicky', Professor C. H. Waddington and Barbara Wootton.[14] Other prominent founding members of CND were Fenner Brockway, E. P. Thompson, A. J. P. Taylor, Anthony Greenwood, Jill Greenwood, Lord Simon, D. H. Pennington, Eric Baker and Dora Russell. Organisations that had previously opposed British nuclear weapons supported CND, including the British Peace Committee, the Direct Action Committee,[15] the National Committee for the Abolition of Nuclear Weapons Tests[14] and the Quakers.[16]

In the same year, a branch of CND was also set in the Republic of Ireland by John de Courcy Ireland, and his wife Beatrice, aiming to campaign for the Irish government to support international efforts to achieve nuclear disarmament and to keep Ireland free of nuclear power.[17] Notable supporters of the Irish CND included Peadar O'Donnell, Owen Sheehy-Skeffington and Hubert Butler.[18]

The formation of CND marked a significant change in the international peace movement, which from the late 1940s had been dominated by the World Peace Council (WPC), an anti-western organisation directed by the Soviet Communist Party. Because the WPC had a large budget and organised high-profile international conferences, the peace movement became identified with the communist cause.[19] CND represented the growth of the unaligned peace movement and its detachment from the WPC.

With a general election due in 1959, which Labour was widely expected to win,[20] CND's founders envisaged a campaign by eminent individuals to secure a government that would adopt its policies: the unconditional renunciation of the use, production of or dependence upon nuclear weapons by Britain and the bringing about of a general disarmament convention; halting the flight of planes armed with nuclear weapons; ending nuclear testing; not proceeding with missile bases; and not providing nuclear weapons to any other country.[14]

In Easter 1958, CND, after some initial reluctance, supported a march from London to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston (a distance of 52 miles), that had been organised by a small pacifist group, the Direct Action Committee. Thereafter, CND organised annual Easter marches from Aldermaston to London that became the main focus for supporters' activity. 60,000 people participated in the 1959 march and 150,000 in the 1961 and 1962 marches.[21][22] The 1958 march was the subject of a documentary by Lindsay Anderson, March to Aldermaston.

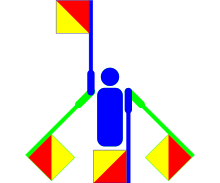

The symbol adopted by CND, designed for them in 1958 by Gerald Holtom,[14] became the international peace symbol. It is based on the semaphore symbols for "N" (two flags held 45 degrees down on both sides, forming the triangle at the bottom) and "D" (two flags, one above the head and one at the feet, forming the vertical line) (for Nuclear Disarmament) within a circle.[23] Holtom later said that it also represented "an individual in despair, with hands palm outstretched outwards and downwards in the manner of Goya's peasant before the firing squad" (although in that painting, The Third of May 1808, the peasant is actually holding his hands upwards).[24] The CND symbol, the Aldermaston march, and the slogan "Ban the Bomb" became icons and part of the youth culture of the 1960s.

CND's supporters were generally left of centre in politics. About three-quarters were Labour voters[16] and many of the early executive committee were Labour Party members.[14] The ethos of CND at that time was described as "essentially that of middle-class radicalism".[25]

In the event, Labour lost the 1959 election, but it voted at its 1960 Conference for unilateral nuclear disarmament, which represented CND's greatest influence and coincided with the highest level of public support for its programme.[26] The resolution was passed against the wishes of the party's leaders and Hugh Gaitskell promised to "fight, fight, and fight again" against the decision. The Campaign for Democratic Socialism was formed to organise in the constituencies and trades unions to have it overturned at the next conference,[27] which duly occurred.[28] Labour's failure to win the election and its rejection of unilateralism in 1961 upset CND's plans. From that date its prospects of success began to fade and it was said that it lacked any clear idea of how nuclear disarmament was to be implemented and that its demonstrations had become ends in themselves.[29] The sociologist Frank Parkin said that, for many supporters, the question of implementation was of secondary importance anyway because, for them, involvement in the campaign was "an expressive activity in which the defence of principles was felt to have higher priority than 'getting things done'."[16] He suggested CND's survival in the face of its failure was explained by the fact that it provided "a rallying point and symbol for radicals", which was more important for them than "its manifest function of attempting to change the government's nuclear weapons policy."[16] Despite setbacks, it retained the support of a significant minority of the population and became a mass movement, with a network of autonomous branches and specialist groups and an increased participation in demonstrations until about 1963.

In 1960, Bertrand Russell resigned from the Campaign in order to form the Committee of 100, which became, in effect, the direct action wing of CND. Russell argued that direct action was necessary because the press was losing interest in CND and because the danger of nuclear war was so great that it was necessary to obstruct government preparations for it.[30] In 1958 CND had cautiously accepted direct action as a possible method of campaigning,[14] but, largely under the influence of its chairman, Canon Collins, the CND leadership opposed any sort of unlawful protest. The Committee of 100 was created as a separate organisation, partly for that reason and partly because of personal animosity between Collins and Russell. Although the committee was supported by many in CND, it has been suggested[31] that the campaign against nuclear weapons was weakened by the friction between the two organisations. The Committee organised large sit-down demonstrations in London and at military bases. It later diversified into other political campaigns, including Biafra, the Vietnam War and housing in the UK. It was dissolved in 1968. When direct action came to the fore again in the 1980s, it was generally accepted by the peace movement as a normal part of protest.[32]

CND's executive committee did not give its supporters a voice in the Campaign until 1961, when a national council was formed and until 1966 it had no formal membership. The relationship between supporters and leaders was unclear, as was the relationship between the executive and the local branches. The executive committee's lack of authority made possible the inclusion within CND of a wide range of views, but it resulted in lengthy internal discussions and the adoption of contradictory resolutions at conferences.[29] There was friction between the founders, who conceived of CND as a campaign by eminent individuals focused on the Labour Party, and CND's supporters (including the more radical members of the executive committee), who saw it as an extra-parliamentary mass movement. Collins was unpopular with many supporters because of his strictly constitutional approach and found himself increasingly out of sympathy with the direction the movement was taking.[33] He resigned in 1964 and put his energies into the International Confederation for Disarmament and Peace.[34]

The Cuban Missile Crisis in the Autumn of 1962, in which the United States blockaded a Soviet attempt to put nuclear missiles on Cuba, created widespread public anxiety about imminent nuclear war and CND organised demonstrations on the issue. However, six months after the crisis, a Gallup Poll found that public concern about nuclear weapons had fallen to its lowest point since 1957,[14] and there was a view (disputed by some CND supporters)[35] that US President John F. Kennedy's perceived success in facing down Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev turned the British public away from the idea of unilateral nuclear disarmament.

On the 1963 Aldermaston march, a clandestine group calling itself Spies for Peace distributed leaflets about a secret government establishment, RSG 6, that the march was passing. The people behind Spies for Peace remain unknown, except for Nicholas Walter, a leading member of the Committee of 100.[36] The leaflet said that RSG 6 was to be the local HQ for a military dictatorship after nuclear war. A large group left the march, against the wishes of the CND leadership, to demonstrate at RSG 6. Later, when the march reached London, there were disorderly demonstrations in which anarchists were prominent, quickly deprecated in the press and in parliament.[14] In 1964 there was only a one-day march, partly because of the events of 1963 and partly because the logistics of the march, which had grown beyond all expectation, had exhausted the organisers.[12] The Aldermaston March was resumed in 1965.

Support for CND dwindled somewhat after the 1963 Test Ban Treaty, one of the things for which it had been campaigning. In addition, from the mid-1960s, the anti-war movement's preoccupation with the Vietnam War tended to eclipse concern about nuclear weapons, but CND continued to campaign against both, and the Easter marches continued to attract considerable support well into the 1970s.

Although CND has never formally allied itself to any political party and has never been an election campaigning body, CND members and supporters have stood for election at various times on a nuclear disarmament ticket. The nearest CND has come to having an electoral arm was the Independent Nuclear Disarmament Election Campaign (INDEC) which stood candidates in a few local elections during the 1960s. INDEC was never endorsed by CND nationally and candidates were generally put up by local branches as a means of raising the profile of the nuclear threat.

The Second Wave: 1980–1983

[edit]In the 1980s, CND underwent a major revival in response to the resurgence of the Cold War. Wave after wave of new members joined as the result of a growing antinuclear movement, the strong motivation of its membership, and criticism of CND objectives by the Thatcher government.[37] There was increasing tension between the superpowers following the deployment of SS20s in the Soviet Bloc countries, American Pershing missiles in Western Europe, and Britain's replacement of the Polaris armed submarine fleet with Trident missiles.[25] The NATO exercise Able Archer 83 also added to international tension.

CND's membership soared; in the early 1980s it claimed 90,000 national members and a further 250,000 in local branches. "This made it one of the largest political organisations in Britain and probably the largest peace movement in the world (outside the state-sponsored movements of the communist bloc)."[25] Public support for unilateralism reached its highest level since the 1960s.[38] In October 1981, 250,000 people joined an anti-nuclear demonstration in London. CND's demonstration on the eve of Cruise missile deployment in October 1983 was one of the largest in British history,[25] with 300,000 taking part in London as three million protested across Europe.[39]

Glastonbury Festival played a key cultural role in this period. The festival's long-term campaigning relationships have been with CND (1981–1990), Greenpeace (1992 onwards), and Oxfam (because of its campaigning against the arms trade), as well as the establishment of the Green Fields as a regular and expanding eco-feature of the festival (from 1984 on). The radical peace movement and the rise of the greens in Britain are interwoven at Glastonbury. The festival has offered these campaigns and groups space on-site to publicise and disseminate their ideas, and it has ploughed large sums of money from the festival profits into them, as well as other causes. June 1981 saw the first Glastonbury CND Festival, and over the 1980s as a decade Glastonbury raised around £1m for CND. The CND logo topped Glastonbury's pyramid stage, while publicity regularly proclaimed proudly: 'This Event is the most effective Anti-Nuclear Fund Raiser in Europe'.[40]

New sections were formed, including Ex-services CND, Green CND, Student CND, Tories Against Cruise and Trident (TACT), Trade Union CND, and Youth CND. More women than men supported CND.[12] The campaign attracted supporters who opposed the Government's civil defence plans as outlined in an official booklet, Protect and Survive. This publication was ridiculed in a popular pamphlet, Protest and Survive, by E. P. Thompson, a leading anti-nuclear campaigner of the period.

The British anti-nuclear movement at this time differed from that of the 1960s. Many groups sprang up independently of CND, some affiliating later. CND's previous objection to civil disobedience was dropped and it became a normal part of anti-nuclear protest. The women's movement had a strong influence, much of it emanating from the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp,[12] followed by Molesworth People's Peace Camp.

A network of protesters, calling itself Cruise Watch, tracked and harassed Cruise missiles whenever they were carried on public roads. After a while, the missiles traveled only at night under police escort.

At its 1982 conference, the Labour Party adopted a policy of unilateral nuclear disarmament. It lost the 1983 general election "in which, following the Falklands war, foreign policy was high on the agenda. Election defeats under, first, Michael Foot, then Neil Kinnock, led Labour to abandon the policy in the late 1980s."[41] The re-election of a Conservative government in 1983 and the defeat of left-wing parties in continental Europe "made the deployment of Cruise missiles inevitable and the movement again began to lose steam."[25]

Extent of support for CND policies

[edit]Membership

[edit]

Until 1967, supporters joined local branches and there was no national membership. An academic study of CND gives the following membership figures from 1967 onwards:[42]

- 1967: 1,500

- 1968: 3,037

- 1969: 2,173

- 1970: 2,120

- 1971: 2,047

- 1972: 2,389

- 1973: 2,367

- 1974: 2,350

- 1975: 2,536

- 1976: 3,220

- 1977: 2,168

- 1978: 3,220

- 1979: 4,287

- 1980: 9,000

- 1981: 20,000

- 1982: 50,000

Under Joan Ruddock's chairmanship from 1981 to 1985, CND said its membership rose from 20,000 to 460,000.[43] The BBC said that in 1985 CND had 110,000 members[44] and in 2006, 32,000.[44] The organisation reported a rapid increase in membership after Jeremy Corbyn, a prominent member, became leader of the Labour Party in 2015.[45]

Opinion polls

[edit]As it did not have a national membership until 1967, the strength of public support in its early days can be estimated only from the numbers of those attending demonstrations or expressing approval in opinion polls. Polls on a number of related issues have been taken over the past fifty years.

- Between 1955 and 1962, between 19% and 33% of people in Britain expressed disapproval of the manufacture of nuclear weapons.[46]

- Public support for unilateralism in September 1982 was 31%, falling to 21% in January 1983, but it is hard to say whether this decline was a result of the counter-CND campaigns or not.[38]

- Support for CND fell after the end of the Cold war. It had not succeeded in converting the British public to unilateralism and even after the collapse of the Soviet Union British nuclear weapons still have majority support.[38] "Unilateral disarmament has always been opposed by a majority of the British public, with the level of support for unilateralism remaining steady at around one in four of the population."[26][47]

- In 2005, MORI conducted an opinion poll which asked about attitudes to Trident and the use of nuclear weapons. When asked whether the UK should replace Trident, without being told of the cost, 44% of respondents said "Yes" and 46% said "No". When asked the same question and told of the cost, the proportion saying "Yes" fell to 33% and the proportion saying "No" increased to 54%.[48]

- In the same poll, MORI asked "Would you approve or disapprove of the UK using nuclear weapons against a country we are at war with?". 9% approved if that country did not have nuclear weapons, and 84% disapproved. 16% approved if that country had nuclear weapons but never used them, and 72% disapproved. 53% approved if that country used nuclear weapons against the UK, and 37% disapproved.[48]

- CND's policy of opposing American nuclear bases is said to be in tune with public opinion.[25]

On three occasions the Labour Party, when in opposition, has been significantly influenced by CND in the direction of unilateral nuclear disarmament. Between 1960 and 1961 it was official Party policy although the Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell opposed the decision and succeeded in quickly reversing it. In 1980 long time CND supporter Michael Foot became Labour Party leader and in 1982 succeeded in changing official Labour policy in line with his views. After losing the 1983 and 1987 general elections Labour leader Neil Kinnock persuaded the party to abandon unilateralism in 1989.[49] In 2015 another long time CND supporter, Jeremy Corbyn was elected leader of the Labour Party, although the official Labour policy did not change in line with his views.[50]

Organised opposition to CND

[edit]CND's growing support in the 1980s provoked opposition from several sources, including Peace Through Nato, the British Atlantic Committee (which received government funding),[51] Women and Families for Defence (set up by Conservative journalist and later MP Lady Olga Maitland to oppose the Greenham Common Peace Camp), the Conservative Party's Campaign for Defence and Multilateral Disarmament, the Coalition for Peace through Security, the Foreign Affairs Research Institute, and The 61, a private sector intelligence agency. The British government also took direct steps to counter the influence of CND, Secretary of State for Defence Michael Heseltine setting up Defence Secretariat 19 "to explain to the public the facts about the Government's policy on deterrence and multilateral disarmament".[52] The activities of anti-CND organisations are said to have included research, publication, mobilising public opinion, counter-demonstrations, working within the Churches, smears against CND leaders and spying.

In an article on anti-CND groups, Stephen Dorril reported that in 1982 Eugene V. Rostow, Director of the US Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, became concerned about the growing unilateralist movement. According to Dorril, Rostow helped to initiate a propaganda exercise in Britain, "aimed at neutralising the efforts of CND. It would take three forms: mobilising public opinion, working within the Churches, and a 'dirty tricks' operation against the peace groups."[53]

One of the groups set up to carry out this work was the Coalition for Peace through Security (CPS), modelled on the US Coalition for Peace through Strength. The CPS was founded in 1981. Its main activists were Julian Lewis, Edward Leigh and Francis Holihan.[53] Amongst the activities of the CPS were commissioning Gallup polls[54] which showed the levels of support for British possession of nuclear weapons, providing speakers at public meetings, highlighting the left-wing affiliations of leading CND figures and mounting counter-demonstrations against CND. These including haranguing CND marchers from the roof of the CPS's Whitehall office and flying a plane over a CND festival with a banner reading, "Help the Soviets, Support CND!"[55] The CPS attracted criticism for refusing to say where its funding came from while alleging that the anti-nuclear movement was funded by the Soviet Union.[56] Although the CPS called itself a grass-roots movement, it had no members and was financed by The 61,[55] "a private sector operational intelligence agency"[57] said by its founder, Brian Crozier, to be funded by "rich individuals and a few private companies".[58] It is said to have also received funding from The Heritage Foundation.[59]

The CPS claimed that Bruce Kent, the general secretary of CND and a Catholic priest, was a supporter of IRA terrorism.[55] Kent alleged in his autobiography that Francis Holihan spied on CND. Dorril claimed:[53]

...that Holihan had organised aerial propaganda, had entered CND offices under false pretences, and that CPS workers had joined CND in order to gain access to the Campaign's 1982 Annual Conference. When Bruce Kent went on a speaking tour of America, Holihan followed him around. Offensive material on Kent was sent to newspapers and radio stations, and demonstrations were organised against him with support from the College Republican Committee.

Allegations of communist influence and intelligence surveillance

[edit]Some of CND's opponents claimed that CND was a communist or Soviet-dominated organisation, a charge its supporters denied.

In 1981, the Foreign Affairs Research Institute, which shared an office with the CPS, was said by Sanity, the CND newspaper, to have published a booklet claiming that Russian money was being used by CND.[53] Lord Chalfont claimed that the Soviet Union was giving the European peace movement £100 million a year, to which Bruce Kent responded, "If they were, it was certainly not getting to our grotty little office in Finsbury Park."[60] In the 1980s, the Federation of Conservative Students (FCS) claimed that one of CND's elected officers, Dan Smith, was a communist. CND sued for defamation and the FCS settled on the second day of the trial, apologised and paid damages and costs.[61]

The British journalist Charles Moore reported a conversation he had with the Soviet double agent Oleg Gordievsky after the death of leading Labour politician Michael Foot. As editor of the newspaper Tribune, says Moore, Foot was regularly visited by KGB agents who identified themselves as diplomats and gave him money. "A leading supporter of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, Foot ... passed on what he knew about debates over nuclear weapons. In return, the KGB gave him drafts of articles encouraging British disarmament which he could then edit and publish, unattributed to their real source, in Tribune."[62] Foot had received libel damages from the Sunday Times for a similar claim made during his lifetime.[63]

The security service (MI5) carried out surveillance of CND members it considered to be subversive and from the late 1960s until the mid-1970s it designated CND as subversive by virtue of its being "communist-controlled".[64] Communists have played an active role in the organisation, and John Cox, its chairman from 1971 to 1977, was a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain;[citation needed] but from the late 1970s, MI5 downgraded CND from "communist-controlled" to "communist-penetrated".[65]

In 1985, Cathy Massiter, an MI5 officer who had been responsible for the surveillance of CND from 1981 to 1983, resigned and made disclosures to a Channel 4 20/20 Vision programme, "MI5's Official Secrets".[66][67] She said that her work was determined more by the political importance of CND than by any security threat posed by subversive elements within it. In 1983, she analysed telephone intercepts on John Cox that gave her access to conversations with Joan Ruddock and Bruce Kent. MI5 also placed a spy, Harry Newton, in the CND office. According to Massiter, Newton believed that CND was controlled by extreme left-wing activists and that Bruce Kent might be a crypto-communist, but Massiter found no evidence to support either opinion.[64] On the basis of Ruddock's contacts, MI5 suspected her of being a communist sympathiser. Speaking in the House of Commons, Dale Campbell-Savours, MP, said:

...it was felt within the service that officers were likely to be questioned about the true political affiliation of Mrs. Joan Ruddock, who became chair of CND in 1983. It was fully recognised by the service that she had no subversive affiliations and therefore should not be recorded under any of the usual subversive categories. In fact, she was recorded as a contact of a hostile intelligence service after giving an interview to a Soviet journalist based in London who was suspected of being a KGB intelligence officer. In Joan Ruddock's file, MI5 recorded special branch references to her movements—usually public meetings—and kept press cuttings and the products of mail and telephone intercepts obtained through active investigation of other targets, such as the Communist party and John Cox. There were police reports recording her appearances at demonstrations or public meetings. There were references to her also in reports from agents working, for example, in the Communist party. These would also appear in her file.[67]

According to Stephen Dorril, at about the same time, Special Branch officers recruited an informant within CND, Stanley Bonnett, on the instructions of MI5.[59] MI5 is also said to have suspected CND's treasurer, Cathy Ashton, of being a communist sympathiser because she shared a house with a communist.[59] When Michael Heseltine became Secretary of State for Defence in 1983, Massiter was asked to provide information for Defence Secretariat 19 (DS19) about leading CND personnel but was instructed to include only information from published sources. Ruddock claims that DS19 released distorted information regarding her political party affiliations to the media and Conservative Party candidates.[68]

MI5 says that it does not now investigate this area.[65]

Anti-communist propagandist Brian Crozier, claimed in his book Free Agent: The Unseen War 1941–1991 (Harper Collins, 1993) that one of his organizations, "The 61", infiltrated a mole into CND in 1979.[59]

In 1990, it was discovered in the archive of the Stasi (the state security service of the former German Democratic Republic) that a member of CND's governing council, Vic Allen, had passed information to them about CND. This discovery was made public in a BBC TV programme in 1999, reviving debate about Soviet links to CND. Allen stood against Joan Ruddock for the leadership of CND in 1985 but was defeated. Ruddock responded to the Stasi revelations by saying that Allen "certainly had no influence on national CND, and as a pro-Soviet could never have succeeded to the chair," and that "CND was as opposed to Soviet nuclear weapons as Western ones."[69][70]

Chairs of CND since 1958

[edit]- Canon John Collins 1958–1964

- Olive Gibbs 1964–1967

- Sheila Oakes 1967–1968

- Malcolm Caldwell 1968–1970

- April Carter 1970–1971

- John Cox 1971–1977

- Bruce Kent 1977–1979

- Hugh Jenkins 1979–1981

- Joan Ruddock 1981–1985

- Paul Johns 1985–1987

- Bruce Kent 1987–1990

- Marjorie Thompson 1990–1993

- Janet Bloomfield 1993–1996

- David Knight 1996–2001

- Carol Naughton 2001–2003

- Kate Hudson 2003–2010

- Dave Webb 2010–2020

- Tom Unterrainer 2020–present

General Secretaries of CND since 1958

[edit]- Peggy Duff 1958–1967

- Dick Nettleton 1967–1973

- Dan Smith 1974–1975

- Duncan Rees 1976–1979

- Bruce Kent 1979–1985

- Meg Beresford 1985–1990

- Gary Lefley, 1990–1994

The post was abolished in 1994 and reinstated in 2010.

- Kate Hudson, 2010–

Archives

[edit]Much of National CND's historical archive is at the London School of Economics and the Modern Records Centre at the University of Warwick. Records of local and regional groups are spread throughout the country in public and private collections.

See also

[edit]- Anti-nuclear movement in the United Kingdom

- Anti-war

- Campaign Against Arms Trade

- Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (NZ)

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- European Nuclear Disarmament

- European Peace Marches

- Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp

- International Day for the Total Elimination of Nuclear Weapons

- Independent Nuclear Disarmament Election Committee

- Koeberg Alert

- List of anti-war organizations

- List of peace activists

- The Lucas Plan

- Mike Cooley

- Nuclear disarmament

- Nuclear-Free Future Award

- Nuclear-free zone

- Nuclear Information Service

- Nuclear proliferation

- Nuclear weapons and the United Kingdom

- Peace movement

- Peace symbols

- Women's Peace Train

- World Peace Council

- Youth for Multilateral Disarmament (YMD)

References

[edit]- ^ "World's best-known protest symbol turns 50". BBC News. London: BBC News Magazine. 20 March 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ "CND's Structure". London: Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ "CND aims and policies". Cnduk.org. Archived from the original on 27 April 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ "Labour Backbench Rebellions since 1997" (PDF). House of Commons Library. 12 June 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2009.

- ^ Herbert, Ian (17 July 2006). "CND membership booms after nuclear U-turn". London: Independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 25 November 2009. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ "CND Constitution" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ CND, The history of CND

- ^ Priestley, J. B., "Britain and the Nuclear Bombs", New Statesman, 2 November 1957.

- ^ Cullingford, Alison (25 January 2018). "Ban the Bomb! CND at Sixty". Special Collections – University of Bradford. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ Fawcett, Matt. "CND 60th Anniversary". Yorkshire Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ Contemporary CND poster advertising the event.

- ^ a b c d John Minnion and Philip Bolsover (eds), The CND Story, Allison and Busby, 1983, ISBN 0-85031-487-9

- ^ "Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND)". Spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Christopher Driver, The Disarmers: A Study in Protest, Hodder and Stoughton, 1964

- ^ "The history of CND". Cnduk.org. 6 August 1945. Archived from the original on 17 June 2004. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d Frank Parkin, Middle Class Radicalism: The Social Bases of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, Manchester University Press, 1968, p. 39.

- ^ Fagan, Kieran (9 April 2006). "John de Courcy Ireland", Obituary. Irish Independent. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ^ Richard S. Harrison, Irish Anti-War Movements. Dublin : Irish Peace 1986 (pp. 59–61).

- ^ "Rainer Santi, 100 years of peace making, International Peace Bureau, January 1991". Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ David E. Butler and Richard Rose, The British General Election of 1959 (1960)

- ^ Peter Barberis, John McHugh, Mike Tyldesley, Encyclopedia of British and Irish Political Organizations, Continuum International Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0-8264-5814-9

- ^ April Carter, "Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament", in Linus Pauling, Ervin László, and Jong Youl Yoo (eds), The World Encyclopedia of Peace, Oxford: Pergamon, 1986. ISBN 0-08-032685-4, (vol. 1, pp. 109–113).

- ^ "Early Defections in March", Manchester Guardian, 5 April 1958

- ^ Information, Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

- ^ a b c d e f James Hinton "Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament", in Roger S. Powers, Protest, Power and Change, Taylor and Francis, 1997, p. 63, ISBN 0-8153-0913-9

- ^ a b April Carter, Direct Action and Liberal Democracy, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973, p. 64.

- ^ S.E.Finer, Anonymous Empire, London: Pall Mall Press, 1966, p. 17

- ^ Robert McKenzie, "Power in the Labour Party: The Issue of 'Intra-Party Democracy'", in Dennis Kavanagh, The Politics of the Labour Party, Routledge, 2013.

- ^ a b Peers, Dave, "The impasse of CND", International Socialism, No. 12, Spring 1963, pp. 6–11.

- ^ Russell, B., "Civil Disobedience", New Statesman, 17 February 1961.

- ^ Taylor, R., Against the Bomb, Oxford University Press, 1988.

- ^ "A brief history of CND". Cnduk.org. 6 August 1945. Archived from the original on 17 June 2004. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ "Collins, (Lewis) John", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ "Oxford Conference of Non-aligned Peace Organizations". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- ^ Nigel Young, "Cuba '62", in Minnion and Bolsover, p. 61

- ^ Natasha Walter, "How my father spied for peace", New Statesman, 20 May 2002

- ^ Paul Byrne, "The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament: the resilience of a protest group." Parliamentary Affairs 40.4 (1987): 517–535.

- ^ a b c Caedel, Martin, "Britain's Nuclear Disarmers", in Laqueur, W., European Peace Movements and the Future of the Western Alliance, Transaction Publishers, 1985, p. 233, ISBN 0-88738-035-2

- ^ David Cortright, Peace: A History of Movements and Ideas, Cambridge University Press, 2008 ISBN 0-521-85402-4

- ^ George McKay (2000) Glastonbury: A Very English Fair (London: Victor Gollancz), 167–168.

- ^ Anti-war Activism in the Information Age

- ^ John Mattausch, A Commitment to Campaign: A Sociological Study of CND, Manchester University Press, 1989

- ^ "Amnesia over CND membership", Julian Lewis [citing The Daily Telegraph, 24 June 1997]

- ^ a b Finlo Rohrer, "Whatever happened to CND?", BBC News Magazine, 5 July 2006

- ^ "CND membership surge gathers pace after Jeremy Corbyn election", The Guardian, 16 October 2015

- ^ W. P. Snyder, The Politics of British Defense Policy, 1945–1962, Ohio University Press, 1964.

- ^ Andy Byrom, "British attitudes on nuclear weapons", Journal of Public Affairs, 7: 71–77, 2007.

- ^ a b "British Attitudes to Nuclear Weapons" Archived 3 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Carvel; Patrick Wintour (10 May 1989). "Kinnock wins accord on defence switch". The Guardian.

- ^ Sawer, Patrick (17 October 2015). "Jeremy Corbyn courts new anti-nuclear row by becoming vice-president of CND". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "British Atlantic Committee Grant (1981)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Lords. 17 December 1981. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ "Section Ds19 (1986)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Written Answers. 21 July 1986. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d The Lobster, No. 3, 1984

- ^ "Archived copy". www.julianlewis.net. Archived from the original on 26 July 2004. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c Wittner, L., The Struggle Against the Bomb, Volume 3, Stanford University Press, 2003.

- ^ Bruce Kent, Undiscovered Ends, pp. 179–181.

- ^ Joseph C. Goulden, "Crozier, covert acts, CIA and Cold War", The Washington Times, 15 May 1994

- ^ Brian Crozier, Letters: Churchill, the CIA and Clinton, The Guardian, 3 August 1998.

- ^ a b c d Tom Mills, Tom Griffin and David Miller, "The Cold War on British Muslims" Archived 13 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Spinwatch, 2011.

- ^ "Soviet funding? Rubbish". 5 April 2012. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012.

- ^ Bruce Kent, Undiscovered Ends, Fount, 1992, pp. 185–6 ISBN 0002159961

- ^ Charles Moore, Charles Moore, "Was Foot a national treasure or the KGB's useful idiot?" The Telegraph, 5 March 2010

- ^ Rhys Williams, [1] "'Sunday Times' pays Foot damages over KGB claim", Independent, Sunday 23 October 2011

- ^ a b Bateman, D., "The Trouble With Harry: A memoir of Harry Newton, MI5 agent", Lobster, Issue 28, December 1994. Accessed 3 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Myths and Misunderstandings". Mi5.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ "Secret State: Timeline". BBC News. 17 October 2002. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ a b "Dale Campbell-Savours, MP, in Business of the House". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 24 July 1986. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ "Domestic Intelligence Agencies: The Mixed Record of the UK's MI5" (PDF). Center for Democracy and Technology. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ Department of the Official Report (Hansard), House of Commons, Westminster . "Commons Hansard". Publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ "I regret nothing, says Stasi spy". BBC News. 20 September 1999. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Arnold, Jacquelyn. "Protest and survive: The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, the Labour Party and civil defence in the 1980s." in Waiting for the revolution (Manchester University Press, 2018) pp. 48–65.

- Bradshaw, Ross, From Protest to Resistance, A Peace News pamphlet (London: Mushroom Books, 1981), ISBN 0-907123-02-3

- Burkett, Jodi. "Gender and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in the 1960s." in Handbook on Gender and War (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2016) pp. 419–437.

- Byrne, Paul. "The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament: the resilience of a protest group." Parliamentary Affairs 40.4 (1987): 517–535.

- Byrne, Paul. Social Movements in Britain (London: Routledge, 1997), ISBN 0-415-07123-2

- Byrne, Paul. The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (Croom Helm: London, 1988), ISBN 0-7099-3260-X

- Driver, Christopher, The Disarmers: A Study in Protest (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1964)

- Grimley, Matthew. "The Church and the Bomb: Anglicans and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, c. 1958–1984." in God and War (Routledge, 2016) pp. 147–164.

- Hill, Christopher R. "Nations of peace: Nuclear disarmament and the making of national identity in Scotland and Wales." Twentieth Century British History 27.1 (2016): 26–50. online

- Hudson, Kate, CND – Now More Than Ever: The Story of a Peace Movement (London: Vision Paperbacks, 2005), ISBN 1-904132-69-3

- Mattausch, John. A Commitment to Campaign: A Sociological Study of CND (Manchester University Press, 1989), ISBN 0-7190-2908-2

- McKay, George. 'Subcultural innovations in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament', Peace Review 16(4) (2004): pp. 429–438.

- McKay, George. Glastonbury: A Very English Fair, chapter 6 'A green field far away: the politics of peace and ecology at the festival', section 'The CND festival' (London: Victor Gollancz, 2000), pp. 161–169.

- Minnion, John, and Philip Bolsover (eds), The CND Story: The first 25 years of CND in the words of the people involved (London: Allison & Busby, 1983), ISBN 0-85031-487-9

- Nehring, Holger. Politics of Security: British and West German Protest Movements and the Early Cold War, 1945–1970 (OUP Oxford, 2013).

- Nehring, Holger. "Diverging perceptions of security: NATO and the protests against nuclear weapons", in Andreas Wenger, et al. (eds), Transforming NATO in the Cold War: Challenges beyond Deterrence in the 1960s (London: Routledge, 2006)

- Nehring, Holger. "From Gentleman's Club to Folk Festival: The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in Manchester, 1958–63", North West Labour History Journal, No. 26 (2001), pp. 18–28

- Nehring, Holger. "National Internationalists: British and West German Protests against Nuclear Weapons, the Politics of Transnational Communications and the Social History of the Cold War, 1957–1964", Contemporary European History, 14, No. 4(2006)

- Nehring, Holger. "Politics, Symbols and the Public Sphere: The Protests against Nuclear Weapons in Britain and West Germany, 1958–1963", Zeithistorische Forschungen, 2, No. 2 (2005)

- Nehring, Holger. "The British and West German Protests against Nuclear Weapons and the Cultures of the Cold War, 1957–64", Contemporary British History, 19, No. 2 (2005)

- Parkin, Frank, Middle-class radicalism: The Social Bases of the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (Manchester University Press, 1968)

- Phythian, Mark. "CND's Cold War." Contemporary British History 15.3 (2001): 133–156.

- Taylor, Richard, and Colin Pritchard, The Protest Makers: The British Nuclear Disarmament of 1958–1965, Twenty Years On (Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1980), ISBN 0-08-025211-7

Primary sources

[edit]- Aulich, James. War Posters: Weapons of Mass Communication (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2007), ISBN 9780500251416

- Clements, Ben. British Public Opinion on Foreign and Defence Policy: 1945–2017 (Routledge, 2018).

- Peggy Duff, Left, Left, Left: A personal account of six protest campaigns 1945–65 (London: Allison and Busby, 1971), ISBN 0-85031-056-3

External links

[edit]Official media pages

[edit]News items

[edit]- McGuffin, Paddy (7 March 2007). "A new generation of CND goes on the march". Telegraph & Argus.

- "Anniversary demo at nuclear site". BBC Online. 2 January 2008.

- Campbell, Duncan; Williams, Rachel (16 February 2008). "CND veterans remain unbowed, 50 years on". The Guardian. London.

- Sengupta, Kim (7 January 2012). "How Thatcher's election win launched secret war on CND". The Independent. London.

- CND membership surge gathers pace after Jeremy Corbyn election. The Guardian. Published 16 October 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament marches back into public arena after years of decline. The Independent. Published 29 January 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

Historic

[edit]- Catalogue of the CND archives, held at the Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick

- Catalogue of the West Midlands CND archives, held at the Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick

- Catalogue of the Trade Union CND archives, held at the Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick

- "Thousands protest against H-bomb". BBC Online. 18 April 1960. Retrieved 8 January 2012. – Report of the 1960 Aldermaston March

- BBC Report of CND Protest in London 22 October 1983

- 20/20 Vision: MI5's Official Secrets

- Exhibition – CND: The story of a peace movement (LSE Archives)

- 'If at first you don't succeed...:fighting against the bomb in the 1950s and 1960s' by Rip Bulkeley, Pete Goodwin, Ian Birchall, Peter Binns and Colin Sparks, International Socialism journal, 2:11, (Winter 1981) – a short Marxist history of CND

- The Papers of Michael Ashburner, an archive collection strong in material on CND, held at Churchill Archives Centre