Data transformation (statistics)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

In statistics, data transformation is the application of a deterministic mathematical function to each point in a data set—that is, each data point zi is replaced with the transformed value yi = f(zi), where f is a function. Transforms are usually applied so that the data appear to more closely meet the assumptions of a statistical inference procedure that is to be applied, or to improve the interpretability or appearance of graphs.

Nearly always, the function that is used to transform the data is invertible, and generally is continuous. The transformation is usually applied to a collection of comparable measurements. For example, if we are working with data on peoples' incomes in some currency unit, it would be common to transform each person's income value by the logarithm function.

Motivation

[edit]Guidance for how data should be transformed, or whether a transformation should be applied at all, should come from the particular statistical analysis to be performed. For example, a simple way to construct an approximate 95% confidence interval for the population mean is to take the sample mean plus or minus two standard error units. However, the constant factor 2 used here is particular to the normal distribution, and is only applicable if the sample mean varies approximately normally. The central limit theorem states that in many situations, the sample mean does vary normally if the sample size is reasonably large. However, if the population is substantially skewed and the sample size is at most moderate, the approximation provided by the central limit theorem can be poor, and the resulting confidence interval will likely have the wrong coverage probability. Thus, when there is evidence of substantial skew in the data, it is common to transform the data to a symmetric distribution[1] before constructing a confidence interval. If desired, the confidence interval for the quantiles (such as the median) can then be transformed back to the original scale using the inverse of the transformation that was applied to the data.[2][3]

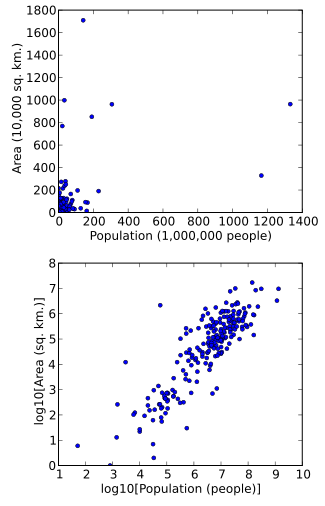

Data can also be transformed to make them easier to visualize. For example, suppose we have a scatterplot in which the points are the countries of the world, and the data values being plotted are the land area and population of each country. If the plot is made using untransformed data (e.g. square kilometers for area and the number of people for population), most of the countries would be plotted in tight cluster of points in the lower left corner of the graph. The few countries with very large areas and/or populations would be spread thinly around most of the graph's area. Simply rescaling units (e.g., to thousand square kilometers, or to millions of people) will not change this. However, following logarithmic transformations of both area and population, the points will be spread more uniformly in the graph.

Another reason for applying data transformation is to improve interpretability, even if no formal statistical analysis or visualization is to be performed. For example, suppose we are comparing cars in terms of their fuel economy. These data are usually presented as "kilometers per liter" or "miles per gallon". However, if the goal is to assess how much additional fuel a person would use in one year when driving one car compared to another, it is more natural to work with the data transformed by applying the reciprocal function, yielding liters per kilometer, or gallons per mile.

In regression

[edit]Data transformation may be used as a remedial measure to make data suitable for modeling with linear regression if the original data violates one or more assumptions of linear regression.[4] For example, the simplest linear regression models assume a linear relationship between the expected value of Y (the response variable to be predicted) and each independent variable (when the other independent variables are held fixed). If linearity fails to hold, even approximately, it is sometimes possible to transform either the independent or dependent variables in the regression model to improve the linearity.[5] For example, addition of quadratic functions of the original independent variables may lead to a linear relationship with expected value of Y, resulting in a polynomial regression model, a special case of linear regression.

Another assumption of linear regression is homoscedasticity, that is the variance of errors must be the same regardless of the values of predictors. If this assumption is violated (i.e. if the data is heteroscedastic), it may be possible to find a transformation of Y alone, or transformations of both X (the predictor variables) and Y, such that the homoscedasticity assumption (in addition to the linearity assumption) holds true on the transformed variables[5] and linear regression may therefore be applied on these.

Yet another application of data transformation is to address the problem of lack of normality in error terms. Univariate normality is not needed for least squares estimates of the regression parameters to be meaningful (see Gauss–Markov theorem). However confidence intervals and hypothesis tests will have better statistical properties if the variables exhibit multivariate normality. Transformations that stabilize the variance of error terms (i.e. those that address heteroscedaticity) often also help make the error terms approximately normal.[5][6]

Examples

[edit]Equation:

- Meaning: A unit increase in X is associated with an average of b units increase in Y.

Equation:

- (From exponentiating both sides of the equation: )

- Meaning: A unit increase in X is associated with an average increase of b units in , or equivalently, Y increases on an average by a multiplicative factor of . For illustrative purposes, if base-10 logarithm were used instead of natural logarithm in the above transformation and the same symbols (a and b) are used to denote the regression coefficients, then a unit increase in X would lead to a times increase in Y on an average. If b were 1, then this implies a 10-fold increase in Y for a unit increase in X

Equation:

- Meaning: A k-fold increase in X is associated with an average of units increase in Y. For illustrative purposes, if base-10 logarithm were used instead of natural logarithm in the above transformation and the same symbols (a and b) are used to denote the regression coefficients, then a tenfold increase in X would result in an average increase of units in Y

Equation:

- (From exponentiating both sides of the equation: )

- Meaning: A k-fold increase in X is associated with a multiplicative increase in Y on an average. Thus if X doubles, it would result in Y changing by a multiplicative factor of .[7]

Alternative

[edit]Generalized linear models (GLMs) provide a flexible generalization of ordinary linear regression that allows for response variables that have error distribution models other than a normal distribution. GLMs allow the linear model to be related to the response variable via a link function and allow the magnitude of the variance of each measurement to be a function of its predicted value.[8][9]

Common cases

[edit]The logarithm transformation and square root transformation are commonly used for positive data, and the multiplicative inverse transformation (reciprocal transformation) can be used for non-zero data. The power transformation is a family of transformations parameterized by a non-negative value λ that includes the logarithm, square root, and multiplicative inverse transformations as special cases. To approach data transformation systematically, it is possible to use statistical estimation techniques to estimate the parameter λ in the power transformation, thereby identifying the transformation that is approximately the most appropriate in a given setting. Since the power transformation family also includes the identity transformation, this approach can also indicate whether it would be best to analyze the data without a transformation. In regression analysis, this approach is known as the Box–Cox transformation.

The reciprocal transformation, some power transformations such as the Yeo–Johnson transformation, and certain other transformations such as applying the inverse hyperbolic sine, can be meaningfully applied to data that include both positive and negative values[10] (the power transformation is invertible over all real numbers if λ is an odd integer). However, when both negative and positive values are observed, it is sometimes common to begin by adding a constant to all values, producing a set of non-negative data to which any power transformation can be applied.[3]

A common situation where a data transformation is applied is when a value of interest ranges over several orders of magnitude. Many physical and social phenomena exhibit such behavior — incomes, species populations, galaxy sizes, and rainfall volumes, to name a few. Power transforms, and in particular the logarithm, can often be used to induce symmetry in such data. The logarithm is often favored because it is easy to interpret its result in terms of "fold changes".

The logarithm also has a useful effect on ratios. If we are comparing positive quantities X and Y using the ratio X / Y, then if X < Y, the ratio is in the interval (0,1), whereas if X > Y, the ratio is in the half-line (1,∞), where the ratio of 1 corresponds to equality. In an analysis where X and Y are treated symmetrically, the log-ratio log(X / Y) is zero in the case of equality, and it has the property that if X is K times greater than Y, the log-ratio is the equidistant from zero as in the situation where Y is K times greater than X (the log-ratios are log(K) and −log(K) in these two situations).

If values are naturally restricted to be in the range 0 to 1, not including the end-points, then a logit transformation may be appropriate: this yields values in the range (−∞,∞).

Transforming to normality

[edit]1. It is not always necessary or desirable to transform a data set to resemble a normal distribution. However, if symmetry or normality are desired, they can often be induced through one of the power transformations.

2. A linguistic power function is distributed according to the Zipf-Mandelbrot law. The distribution is extremely spiky and leptokurtic, this is the reason why researchers had to turn their backs to statistics to solve e.g. authorship attribution problems. Nevertheless, usage of Gaussian statistics is perfectly possible by applying data transformation.[11]

3. To assess whether normality has been achieved after transformation, any of the standard normality tests may be used. A graphical approach is usually more informative than a formal statistical test and hence a normal quantile plot is commonly used to assess the fit of a data set to a normal population. Alternatively, rules of thumb based on the sample skewness and kurtosis have also been proposed.[12][13]

Transforming to a uniform distribution or an arbitrary distribution

[edit]If we observe a set of n values X1, ..., Xn with no ties (i.e., there are n distinct values), we can replace Xi with the transformed value Yi = k, where k is defined such that Xi is the kth largest among all the X values. This is called the rank transform,[14] and creates data with a perfect fit to a uniform distribution. This approach has a population analogue.

Using the probability integral transform, if X is any random variable, and F is the cumulative distribution function of X, then as long as F is invertible, the random variable U = F(X) follows a uniform distribution on the unit interval [0,1].

From a uniform distribution, we can transform to any distribution with an invertible cumulative distribution function. If G is an invertible cumulative distribution function, and U is a uniformly distributed random variable, then the random variable G−1(U) has G as its cumulative distribution function.

Putting the two together, if X is any random variable, F is the invertible cumulative distribution function of X, and G is an invertible cumulative distribution function then the random variable G−1(F(X)) has G as its cumulative distribution function.

Variance stabilizing transformations

[edit]Many types of statistical data exhibit a "variance-on-mean relationship", meaning that the variability is different for data values with different expected values. As an example, in comparing different populations in the world, the variance of income tends to increase with mean income. If we consider a number of small area units (e.g., counties in the United States) and obtain the mean and variance of incomes within each county, it is common that the counties with higher mean income also have higher variances.

A variance-stabilizing transformation aims to remove a variance-on-mean relationship, so that the variance becomes constant relative to the mean. Examples of variance-stabilizing transformations are the Fisher transformation for the sample correlation coefficient, the square root transformation or Anscombe transform for Poisson data (count data), the Box–Cox transformation for regression analysis, and the arcsine square root transformation or angular transformation for proportions (binomial data). While commonly used for statistical analysis of proportional data, the arcsine square root transformation is not recommended because logistic regression or a logit transformation are more appropriate for binomial or non-binomial proportions, respectively, especially due to decreased type-II error.[15][3]

Transformations for multivariate data

[edit]Univariate functions can be applied point-wise to multivariate data to modify their marginal distributions. It is also possible to modify some attributes of a multivariate distribution using an appropriately constructed transformation. For example, when working with time series and other types of sequential data, it is common to difference the data to improve stationarity. If data generated by a random vector X are observed as vectors Xi of observations with covariance matrix Σ, a linear transformation can be used to decorrelate the data. To do this, the Cholesky decomposition is used to express Σ = A A'. Then the transformed vector Yi = A−1Xi has the identity matrix as its covariance matrix.

See also

[edit]- Arcsin

- Feature engineering

- Logit

- Nonlinear regression § Transformation

- Pearson correlation coefficient

- Power transform (Box–Cox)

- Wilson–Hilferty transformation

- Whitening transformation

References

[edit]- ^ Kuhn, Max; Johnson, Kjell (2013). Applied predictive modeling. New York. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6849-3. ISBN 9781461468493. LCCN 2013933452. OCLC 844349710. S2CID 60246745.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Altman, Douglas G.; Bland, J. Martin (1996-04-27). "Statistics notes: Transformations, means, and confidence intervals". BMJ. 312 (7038): 1079. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7038.1079. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 2350916. PMID 8616417.

- ^ a b c "Data transformations - Handbook of Biological Statistics". www.biostathandbook.com. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- ^ "Lesson 9: Data Transformations | STAT 501". newonlinecourses.science.psu.edu. Retrieved 2019-03-17.

- ^ a b c Kutner, Michael H.; Nachtsheim, Christopher J.; Neter, John; Li, William (2005). Applied linear statistical models (5th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill Irwin. pp. 129–133. ISBN 0072386886. LCCN 2004052447. OCLC 55502728.

- ^ Altman, Douglas G.; Bland, J. Martin (1996-03-23). "Statistics Notes: Transforming data". BMJ. 312 (7033): 770. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7033.770. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 2350481. PMID 8605469.

- ^ "9.3 - Log-transforming Both the Predictor and Response | STAT 501". newonlinecourses.science.psu.edu. Retrieved 2019-03-17.

- ^ Turner, Heather (2008). "Introduction to Generalized Linear Models" (PDF).

- ^ Lo, Steson; Andrews, Sally (2015-08-07). "To transform or not to transform: using generalized linear mixed models to analyse reaction time data". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 1171. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01171. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 4528092. PMID 26300841.

- ^ "Transformations: an introduction". fmwww.bc.edu. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- ^ Van Droogenbroeck F.J., 'An essential rephrasing of the Zipf-Mandelbrot law to solve authorship attribution applications by Gaussian statistics' (2019) [1]

- ^ Kim, Hae-Young (2013-02-01). "Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis". Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics. 38 (1): 52–54. doi:10.5395/rde.2013.38.1.52. ISSN 2234-7658. PMC 3591587. PMID 23495371.

- ^ "Testing normality including skewness and kurtosis". imaging.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

- ^ "New View of Statistics: Non-parametric Models: Rank Transformation". www.sportsci.org. Retrieved 2019-03-23.

- ^ Warton, D.; Hui, F. (2011). "The arcsine is asinine: the analysis of proportions in ecology". Ecology. 92 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1890/10-0340.1. hdl:1885/152287. PMID 21560670.

External links

[edit]- Log Transformations for Skewed and Wide Distributions – discussing the log and the "signed logarithm" transformations (A chapter from "Practical Data Science with R").