Dakota Territory

| Territory of Dakota | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organized incorporated territory of the United States | |||||||||||||||||

| 1861–1889 | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||||

| • Type | Organized incorporated territory | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

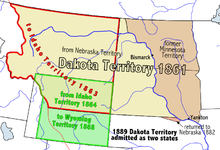

• Created from Nebraska and unorganized territories | 2 March 1861 | ||||||||||||||||

• Idaho Territory split off | March 4, 1863 | ||||||||||||||||

• Land received from Idaho Territory | May 28, 1864 | ||||||||||||||||

• Wyoming Territory split off | July 25, 1868 | ||||||||||||||||

• North Dakota and South Dakota statehood | 2 November 1889 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861,[1] until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of North and South Dakota.

History

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 4,837 | — |

| 1870 | 14,181 | +193.2% |

| 1880 | 158,724 | +1019.3% |

| Source: 1860–1880 (includes both North Dakota and South Dakota;[2] | ||

The Dakota Territory consisted of the northernmost part of the land acquired in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, as well as the southernmost part of Rupert's Land, which was acquired in 1818 when the boundary was changed to the 49th parallel. The name refers to the Dakota branch of the Sioux tribes which occupied the area at the time. Most of Dakota Territory was formerly part of the Minnesota and Nebraska territories.[3]

When Minnesota became a state in 1858, the leftover area between the Missouri River and Minnesota's western boundary fell unorganized. When the Yankton Treaty was signed later that year, ceding much of what had been Sioux Indian land to the U.S. Government, early settlers formed a provisional government and unsuccessfully lobbied for United States territory status.[4] Wilmot Wood Brookings was the provisional governor. The cities of Wilmot and Brookings as well as Brookings County are named for him.[4] Three years later, President-elect Abraham Lincoln's cousin-in-law John Blair Smith Todd personally lobbied for territory status, and the U.S. Congress formally created Dakota Territory. It became an organized territory on March 2, 1861. Upon creation, Dakota Territory included much of present-day Montana and Wyoming as well as all of present-day North Dakota and South Dakota and a small portion of present-day Nebraska.[5] President Lincoln appointed Dakota Territory's first governor, William Jayne, who was Lincoln's old friend and neighbor from Springfield, Illinois.[6]

A small patch of land known as "Lost Dakota" existed as a remote exclave of Dakota Territory until it became part of Gallatin County, Montana Territory, in 1873.[7]

All land north of the Keya Paha River (which includes most of Boyd County, Nebraska, and a smaller portion of neighboring Keya Paha County) was originally part of Dakota Territory, but was transferred to Nebraska in 1882.

American Civil War

[edit]Dakota Territory was not directly involved in the American Civil War but did raise some troops to defend the settlements following the Dakota War of 1862 which triggered hostilities with the Sioux tribes of Dakota Territory. The Department of the Northwest sent expeditions into Dakota Territory in 1863, 1864 and 1865. It also established forts in Dakota Territory to protect the frontier settlements of the Territory, Iowa and Minnesota and the traffic along the Missouri River.

Before statehood

[edit]

Following the Civil War, hostilities continued with the Sioux until the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. By 1868, creation of new territories reduced Dakota Territory to the present boundaries of the Dakotas. Territorial counties were defined in 1872, including Bottineau County, Cass County and others.

During the existence of the organized territory, the population first increased very slowly and then very rapidly with the "Dakota Boom" from 1870 to 1880.[9] Because the Sioux were considered very hostile and a threat to early settlers, the white population grew slowly. Gradually, the settlers' population grew and the Sioux were not considered as severe a threat.[10]

The population increase can largely be attributed to the growth of the Northern Pacific Railroad. Settlers who came to the Dakota Territory were from other western territories as well as many from northern and western Europe. These included large numbers of Norwegians, Germans, Swedes, and Canadians. [11]

Commerce was originally organized around the fur trade. Furs were carried by steamboat along the rivers to the settlements. Gold was discovered in the Black Hills in 1874 and attracted more settlers, setting off the last Sioux War. The population surge increased the demand for meat spurring expanded cattle ranching on the territory's vast open ranges. With the advent of the railroad agriculture intensified: wheat became the territory's main cash crop. Economic hardship hit the territory in the 1880s due to lower wheat prices and a drought.[12]

Regionalist tensions between the northern and the southern parts of the territory were present since the beginning. The southern part was always more populated, in the 1880 Census, the southern part had a population of 98,268, two and a half times the northern part's 36,909. The southern part also considered the north to be somewhat disreputable, "too much controlled by the wild folks, cattle ranchers, fur traders” and too frequently the site of conflict with the indigenous population. The railroad also connected the northern and southern parts to different hubs – the northern part, via Fargo and Bismarck became closer tied to the Minneapolis–Saint Paul area, while the southern part became closer tied to Sioux City and from there to Omaha.

Politically, territorial legislators were appointed by the federal government, and tended to remain in the region only while they served their terms. The larger population of the southern region began to resent them, while the northerners tended to emphasize that it was cheaper to be a territory, with the federal government funding a wide range of state functions.[13]

The last straw was territorial governor Nehemiah G. Ordway moving the territorial capital from Yankton to Bismarck in 1883. As the southern part had crossed the 60,000 population necessary for statehood, in September, they held a convention, where they drafted a state constitution and submitted it to the voters. It was approved by the electors and submitted to Congress. A bill providing for statehood of the Dakota Territory south of the 46th parallel of latitude was passed by the Senate in December 1884, but failed to pass the House. A second constitutional convention for South Dakota was held in September 1885, framing a new constitution and submitted it to the vote of the people, who ratified it with an overwhelming vote.

Conventions favoring division of Dakota into two states were also held in the northern section, one in 1887 at Fargo, and another in 1888, at Jamestown. Both adopted provisions memorializing Congress to divide the territory and admit both North and South Dakota as states. Various bills were introduced in Congress on the matter; one in 1885 to admit South Dakota as a state, and organize the northern half as Lincoln Territory. Another bill introduced in 1886, proposed to admit the entire Territory as a single state. Still another provided for all of the Territory east of the Missouri River to become a single state, the balance to be organized as Lincoln or North Dakota Territory. Other bills were introduced in 1887 and 1888, but failed to pass. The Territorial Legislature of 1887 submitted the question of division to a popular vote at the general election of November 1887. When full returns of this election finally came in on January 10, 1888, Territorial Governor Louis K. Church announced the vote: 37,784 favored division and 32,913 were opposed.[14]

The admission of new western states was a party political battleground, with each party looking at how the proposed new states were likely to vote. At the beginning of 1888, the Democrats under president Grover Cleveland proposed that the four territories of Montana, New Mexico, Dakota and Washington should be admitted together. The first two were expected to vote Democratic and the latter two were expected to vote Republican so this was seen as a compromise acceptable to both parties.[citation needed] However, the Republicans won majorities in both the House and the Senate later that year. To head off the possibility that Congress might only admit Republican territories to statehood[citation needed], the Democrats agreed to a less favorable deal in which Dakota was divided in two and New Mexico was left out altogether. Cleveland signed it into law on February 22, 1889, and the territories could become states nine months after that.

There had been previous attempts to open up the territory, but these had foundered because the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) required that 75 percent of Sioux adult males on the reservation had to agree to any treaty change. Most recently, a commission headed by Richard Henry Pratt in 1888 had completely failed to get the necessary signatures in the face of opposition from Sioux leaders and even government worker Elaine Goodale, later Superintendent of Indian Education for the Dakotas. The government believed that the Dawes Act (1887), which attempted to move the Indians from hunting to farming, in theory, meant that they needed less land (but in reality was an economic disaster for them) and that at least half was available for sale. Congress approved an offer of $1.25 per acre ($3.1/ha) for reservation land (a figure they had previously rejected as outrageously high) and $25,000 to induce the Indians to sign.

A new commission was appointed in April 1889 that included veteran Indian fighter general George Crook. Crook pulled out all the stops to get the Indians to sign, using many underhand tactics. He threatened them that if they did not sign, the land would be taken anyway and they would get nothing. This would not have been seen as an idle threat; the treaty had been ignored in the past when the Black Hills were taken from the Sioux. Crook ignored leaders like Sitting Bull and Red Cloud who opposed the sale and kept them out of the negotiations, preferring instead to deal with moderate leaders like American Horse. American Horse, however, claimed immediately afterwards that he had been tricked into signing. Crook made many personal promises (such as on reservation rations) which he had no authority to make, or ability to keep. He claimed afterwards that he had only agreed to report the concerns back to Washington. Crook lied about how many signatures he already had, giving the impression that the signature he was currently asking for would make no difference. He said that those who did not sign would not get a share of the money for the land. Crook even allowed white men who had married Sioux to sign, a dubious action given that the blood quantum laws only counted full-blood Indians as members of the tribe. By August 6, 1889, Crook had the requisite number of signatures, half the reservation land was sold, and the remainder divided among six smaller reservations.

Statehood

[edit]On February 22, 1889, outgoing President Cleveland signed an omnibus bill that divided the Territory of Dakota in half. North Dakota and South Dakota became states simultaneously on November 2, 1889.[15] President Harrison had the papers shuffled to obscure which one was signed first and the order went unrecorded.[16] The bill also enabled the people in the new Territories of North Dakota and South Dakota, as well as the older territories of Montana and Washington, to write state constitutions and elect state governments. The four new states would be admitted into the Union in nine months. This plan cut Democratic New Mexico out of statehood and split Republican Dakota Territory into two new Republican states. Rather than two new Republican states and two new Democratic states that Congress had considered the previous year, the omnibus bill created three new Republican states and one new Democratic state that Republicans thought they would capture.

See also

[edit]- Bibliography of North Dakota history

- Bibliography of South Dakota history

- List of governors of Dakota Territory

- American frontier

- Historic regions of the United States

- History of North Dakota

- History of South Dakota

- List of Dakota Territory Civil War units

- Territorial evolution of the United States

- Dakota Territory's at-large congressional district

- Railroad land grants in the United States#Northern Pacific

Notes

[edit]- ^ The territory's great seal was enacted by a law passed on January 3, 1863, with a design described as follows:[8]

A tree in the open field, the trunk of which is surrounded by a bundle of rods, bound with three bands; on the right plow, anvil, sledge, rake and fork; on the left, bow crossed with three arrows; Indian on horseback pursuing a buffalo toward the setting sun; foliage of the tree arched by half circle of thirteen stars, surrounded by the motto: "Liberty and Union, one and inseparable, now and forever", the words "Great Seal" at the top, and at the bottom, "Dakota Territory"; on the left, "March 2"; on the right, "1861". Seal 2+1⁄2 inches [64 mm] in diameter.

References

[edit]- ^ 12 Stat. 239

- ^ Forstall, Richard L. (ed.). Population of the States and Counties of the United States: 1790–1990 (PDF) (Report). United States Census Bureau. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 18, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ "Dakota Territory | Encyclopedia.com". Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ a b "A Spirited Pioneer Promoter". Archived from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ "Dakota Territory Records – State Agencies – Archives State Historical Society of North Dakota -". Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ "Section 1: Dakota Territory | North Dakota Studies". Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- ^ "Beyond 50: American States That Might Have Been". npr.org. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ Kingsbury, George W. (1915). History of Dakota Territory. Vol. 1. Chicago: The S. J. Clarke Publishing Company. p. 268 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ The New Encyclopedia of the American West. Ed. Howard R. Lamar. 1998 Yale University Press, New Haven. pp. 282

- ^ Encyclopedia of the American West. Ed. Charles Philips and Alan Axelrod. 1996 Macmillan Reference USA, New York. pp.1200–1201

- ^ John H. Hudson, “Migration to an American Frontier.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 66#2 (1976), pp. 242–65, at 243–244; online

- ^ The New Encyclopedia of the American West, 282

- ^ "Now You Know: Why Are There Two Dakotas?". Time. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ "Moving Toward Statehood | North Dakota Studies". October 17, 2015. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ "Section 6: Statehood | North Dakota Studies". Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ "Now You Know: Why Are There Two Dakotas?". July 14, 2016. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Dakota Territory Centennial Commission (1961). Dakota Panorama. Dakota Territory Centennial Commission. OCLC 2063074.

- Lamar, Howard. Dakota Territory, 1861-1889: A Study of Frontier Politics (Yale UP, 1956) online

- Lauck, Jon K. (2010). Prairie Republic: The Political Culture of Dakota Territory, 1879–1889. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806141107. OCLC 455419815.

- Lauck, Jon. "The Old Roots of the New West: Howard Lamar and the Intellectual Origins of ‘Dakota Territory.’" Western Historical Quarterly 39#3 (2008), pp. 261–81. online

- Waldo, Edna La Moore (1936). Dakota. The Caxton printers, Ltd. OCLC 1813068.