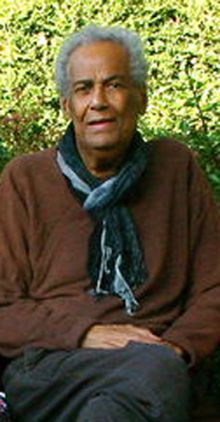

Cy Grant

Cy Grant | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Cyril Ewart Lionel Grant 8 November 1919 |

| Died | 13 February 2010 (aged 90) London, England |

| Occupation(s) | Actor, musician, writer, poet |

| Years active | 1951–1994 |

| Style | Calypso music, folk music, steelpan music |

| Spouse |

Dorith Grant (m. 1956) |

| Children | 4 |

| Website | cygrant |

Cyril Ewart Lionel Grant (8 November 1919 – 13 February 2010) was a Guyanese actor, musician, writer, poet and World War II veteran. In the 1950s, he became the first black person to be featured regularly on television in Britain,[1][2][3] mostly due to his appearances on the BBC current affairs show Tonight.

Following service in the Royal Air Force during World War II, Grant worked as an actor and singer, before establishing the Drum Arts Centre in London in the 1970s.[4] In the 1980s, he was appointed director of Concord Multicultural Festivals.[5] A published poet and author of several books, including his 2007 memoir Blackness and the Dreaming Soul and other writing that reflected his belief in Taoism and an expansive world view,[6] Grant was made an Honorary Fellow of Roehampton University in 1997, and a member of the Scientific and Medical Network in 2001. In 2008, he was the founder and inspirator of an online archive to trace and commemorate Caribbean airmen of the Second World War.[7]

A father of four children, Grant lived with his wife, Dorith (1927–2018),[8] in Highgate, London.

Early life

[edit]Cyril Ewart Lionel Grant was born on 8 November 1919 into a middle-class family in Beterverwagting, which was then in British Guiana (now in Guyana). His mother was a music teacher from Antigua, while his father was a Moravian minister. He had two brothers and four sisters.[9] At the age of 11, he moved with his family to New Amsterdam. After leaving high school, he worked as a clerk in the office of a stipendiary magistrate but was unable to study law overseas due to a lack of funds.[10]

Speaking of his upbringing, Grant said, "I was brought up in a typically colonial way, singing 'Rule Britannia' and learning about English history and geography, but not knowing anything about the country I was born in. I knew as a young person in Guyana that something was wrong... I felt frustrated by the colonial way of life. I knew that the colony was too small to hold me."[11]

Military service

[edit]In 1941, Grant joined the Royal Air Force, which had extended recruitment to non-white candidates following heavy losses in the early years of the Second World War. One of approximately 500 young men recruited from the Caribbean as aircrew, he was commissioned as an officer after training in England as a navigator. He was quoted as saying: "As an officer in the RAF, you were among the cream of officers. I met all sorts of people, including writers, schoolteachers, lecturers and scientists. And, living for two years close together, I learnt a great deal and asked a lot of questions – that's where I matured, actually."[12] He joined 103 Squadron, based at RAF Elsham Wolds in Lincolnshire,[13] becoming one of a seven-man crew of an Avro Lancaster.

In 1943, on his third operation, Flight Lieutenant Grant was shot down over The Netherlands during the Battle of the Ruhr. He parachuted to safety into a field (south of Nieuw-Vennep, as he later found out) and was helped by a Dutch family, although a policeman subsequently handed him over to the German forces, and for the next two years Grant was imprisoned in Stalag Luft III camp, 160 kilometres (99 mi) east of Berlin.[14] (The camp is best known for two famous prisoner escapes that took place there by tunnelling, which were depicted in the films The Great Escape (1963) and The Wooden Horse (1950), and the books by former prisoners Paul Brickhill and Eric Williams from which these films were adapted.) Grant was eventually liberated by the Allied Forces in 1945.[15] One of those who in 1943 had rushed to the scene of the crash in the Dutch village was a then 11-year-old local called Joost Klootwijk, who in later years determined to find out what happened to the crew and eventually made contact with Grant around 2007.[16] BBC London Special Correspondent Kurt Barling made a film in 2008 of Grant returning after 65 years to the Netherlands, where Grant and Klootwijk had an emotional meeting for the first time.[17]

In 2007, Grant participated in the filming of the documentary Into the Wind (2011), in which he discusses his experiences as an RAF navigator.[18]

Showbusiness career

[edit]After the war, Grant decided to pursue his original ambition to study law, perceiving it as a means to challenge racism and social injustice. He became a member of the Middle Temple in London and qualified as a barrister in 1950. However, despite his distinguished war record and legal qualifications, he was unable to find work at the Bar and decided to take up acting. Aside from earning a living, he saw acting as a way to improve his diction in preparation for when he finally entered Chambers.[19]

Grant's first acting role was for a Moss Empires tour in which he starred in a play titled 13 Death St., Harlem. His career received a boost after he successfully auditioned for Laurence Olivier and his Festival of Britain Company, which led to appearances at the St. James Theatre in London and the Ziegfeld Theatre in New York City (alongside Jan Carew).[20] Aware of the short supply of roles for black actors, Grant decided to increase his earning potential by becoming a singer, having learnt to sing and play the guitar during his childhood in Guiana. This proved to be a successful undertaking and Grant soon appeared in revues and cabaret venues such as Esmeralda's Barn, singing Caribbean and other folk songs, as well as on BBC radio (The Third Programme and the Overseas Service). In 1956, he was the first black person to host his own television series,[21] For Members Only (broadcast on Associated Television), on which he interspersed interviews with newsworthy people with singing and playing the guitar.[22]

In 1956, Grant appeared alongside Nadia Cattouse, Errol John and Earl Cameron in the BBC TV drama Man From The Sun, whose characters are mostly Caribbean migrants to London,[23] and also starred in the World War II film Sea Wife (1957), with Richard Burton and Joan Collins. The following year, Grant was asked to feature in the BBC's daily topical programme, Tonight, to "sing" the news in the form of a "topical Calypso" (a pun on "tropical"). With journalist Bernard Levin providing words, Grant strung them together. Tonight was popular and made Grant a well-known public figure, the first black person to appear regularly on British television. However, not wanting to become typecast, he stepped down from this position after two and a half years.[19]

His acting career continued apace and later in 1957 he appeared in Home of the Brave, an award-winning TV drama by Arthur Laurents, and travelled the following year to Jamaica for the filming of Calypso, in which he played the romantic lead.

In 1964, Grant appeared in the musical The Roar of the Greasepaint – The Smell of the Crowd, in which he was the first to perform the song "Feeling Good", later covered by many others. He included a version of the song on his 1965 album, Cy & I.

Grant's general frustration with the lack of good roles for black actors was briefly tempered in 1965 when he played the lead in Shakespeare's Othello at the Phoenix Theatre in Leicester, a role for which white actors at the time routinely "blacked up".[10]: 36–37 Between 1967 and 1968 Grant also voiced the character of Lieutenant Green in Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons.

A brief return to the Bar in 1972 reflected Grant's disenchantment with show business, as well as his growing politicisation. After six months at a Chambers in the Middle Temple, he decided that he no longer had any passion for law and resolved to challenge discrimination through the arts.[10]: 38

Music career

[edit]Grant performed Caribbean calypso and folk songs in many countries, at venues including Esmeralda's Barn in London (1950s), the New Stanley Hotel, Nairobi (1973), Bricktops, Rome (1956), and for the GTV 9 station in Melbourne, Australia. In addition, he entertained British armed forces in Cyprus, the Maldives, Singapore and Libya. His concert appearances include the Kongresshalle of the Deutsches Museum in Munich (1963) and Queen Elizabeth Hall in London (1971). In 1989, he helped to organise the "One Love Africa, Save The Children International Music Festival" in Zimbabwe.

Grant recorded five LPs. His album Cool Folk (World Record Club, 1964) – featuring "Where Have All the Flowers Gone?", "Yellow Bird", "O Pato", "Blowin' in the Wind", "Work Song", and "Every Night When the Sun Goes Down" – is a collector's item. Other LPs include Cy Grant (Transatlantic Records), Cy & I (World Record Club), Ballads, Birds & Blues, (Reality Records) and Cy Grant Sings (Donegall Records). Two of Grant's singles, "King Cricket" and "The Constantine Calypso", recorded in 1966 for Pye Records, celebrate the lives of West Indian cricketers Garfield Sobers and Learie Constantine.[24] The songs were featured in the 2009 BBC Two television documentary series Empire of Cricket.

Grant had extensive involvement in British radio broadcasting. The BBC Sound Archive contains more than 90 entries for his radio work, dating from 1954 to 1997. These include a series of six meditations based on 24 of the 81 chapters of the Tao te Ching for the BBC World Service in 1980, The Way of the Tao (Grant was a devotee of Taoism);[6] The Calypso Chronicles, six programmes for BBC Radio 2 (1994); Panning for Gold, two programmes for Radio 2; Amazing Grace, Radio 2; and Day Light Come and Wild Blue, both for BBC Radio 4.

Grant discussed his experiences of being among the first generation of Afro-Caribbean actors in Britain in TV's Black Pioneers, broadcast on BBC Four in June 2007, and Black Screen Britain, Part 1: Ambassadors for the Race, broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2009.

Activism

[edit]In collaboration with Zimbabwean John Mapondera, in 1974 Grant set up the Drum Arts Centre in London (not to be confused with The Drum in Birmingham) to provide a springboard and a national centre for black artistic talent.[25] Laurence Olivier rebuffed Grant's invitation to become a patron of Drum, accusing him of being separatist.[26] As recalled by Gus John, a Drum trustee (other trustees included Tania Rose, Chris Konyils, Helen McEachrane, Gurmukh Singh, Eric Smellie and Margaret Busby), Grant said of the prevailing mainstream climate at the time: "These people are simply incapable of seeing the world through our lenses, incapable of imagining for just one moment what it must be like for us to experience their system which to us is anything but as open as they would have us believe. They therefore see our self-organisation as an affront."[21]

Considered a landmark in the development of black theatre,[27] Drum counted among its highlights a series of workshops held in 1975 at Morley College by Steve Carter of the New York Negro Ensemble Company.[2] This led to a production of Mustapha Matura's Bread at the Young Vic and workshops with the Royal National Theatre. In 1977, Ola Rotimi produced a Nigerian adaptation of Sophocles' Oedipus Rex, titled The Gods Are Not to Blame, at the Greenwich Theatre and Jackson's Lane Community Centre; meanwhile, The Swamp Dwellers by Wole Soyinka was produced at the Commonwealth Institute Theatre. The Drum Arts Centre also premiered Sweet Talk by Michael Abbensetts at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in 1975. Among the exhibitions Drum mounted was Behind the Mask: Afro-Caribbean Poets and Playwrights in Words and Pictures at the Commonwealth Institute and the National Theatre in 1979.

Grant stood down as chair of the Drum Arts Centre in 1978 following internal disagreements, giving him the opportunity to concentrate on a one-man show adapted from Aimé Césaire's epic poem Cahier d'un retour au pays natal (Notebook of a Return to My Native Land).[28] A critique of European colonialism and values, it was cited by Grant as a major influence on his thought.[19] After a platform performance at the National Theatre and a two-week production at the Theatre Upstairs, Royal Court Theatre,[29] Grant embarked on a two-year national tour in 1977.

In 1981, Grant became director of Concord Multicultural Festivals,[5] which in the course of the four years staged 22 multicultural festivals in cities in England and Wales, starting in Nottingham.[6] These were followed by two national festivals, in Devon (1986) and Gloucestershire (1987). Both lasted several months and involved a vast range of local, national and international artistes, as well as workshops, in an attempt to celebrate the cultural diversity of modern-day Britain and foster improved race relations.[3]

In 2007, Grant helped open the London, Sugar and Slavery permanent exhibition hosted at the Museum of London Docklands.[30]

Awards

[edit]In 1997, Grant was awarded an honorary fellowship by the University of Surrey Roehampton.[31]

Death

[edit]Grant died at University College Hospital, London, on 13 February 2010 at the age of 90.[32] He was survived by his wife Dorith (whom he married in 1956),[8] their two daughters and one son (Dana, Sami and Dominic), and his son from an earlier marriage, Paul.[21][33]

Legacy and honours

[edit]Before Grant's death, the Bomber Command Association had planned to honour him as an "'inspirational example' of how black and white servicemen and women fought alongside one another in two world wars", and a posthumous ceremony took place the following month at the House of Lords, where his younger daughter Samantha (Sami) Moxon was presented with a plaque bearing the citation that Flt Lt Grant had "valiantly served in World War Two to ensure our freedom".[34] He had originally been invited to an award presentation in the US in 2009 at a "Caribbean Glory" event organised by Gabriel Christian to raise the profile of West Indians' contribution in two world wars, but illness had prevented Grant from attending.[35][34]

Other tributes have included events at the British Film Institute: "Cy Grant Day at the BFI: Tribute to a Hero", on 7 November 2010 (hosted by Burt Caesar,[36] and on 12 November 2016 "Life and Times of Cy Grant", with the participation of Professor Kurt Barling, producer Terry Jervis, theatre director Yvonne Brewster, and the High Commissioner of Guyana.[37]

A blue plaque erected on 11 November 2017 by the Nubian Jak Community Trust marks Grant's former home at 54 Jackson's Lane, Highgate, in London.[38][39][40]

The Cy Grant Archive

[edit]The Cy Grant Trust has been set up by his family to preserve Grant's work,[41] with a project to promote his legacy to the wider community, in partnership with London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), assisted by the Windrush Foundation and others. Following an award from the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF),[42] in spring 2016 the Cy Grant Archive was launched – comprising documents, manuscripts, photographs and films dating from the 1940s to 2010 – and will be catalogued and made public for the first time.[43] Speaking of the importance to her family of the project, which includes an outreach programme involving workshops, school education packs, online resources and a touring exhibition,[44] aimed at raising awareness of Grant's achievements and inspiring younger generations, Samantha Moxon said: "My dad's dream was that the importance of his work should be recognised and never forgotten."[6]

A celebration event at LMA in February 2017 marked the launch of the archive catalogue.[45][46]

Caribbean Aircrew Archive

[edit]Grant wrote in 2009:

"In researching my war memoir, A Member of the RAF of Indeterminate Race, I found that neither the Air Ministry, the MOD, nor the Imperial War Museum had complete records of air crew from the Caribbean, whether of obvious 'hero potential' or not. This prompted me to set the record straight.... And with the assistance of my friend and webmaster, Hans Klootwijk...we have set up an online archive to trace and commemorate for all time, all those whose services have not been acknowledged."[47]

Launched in 2006, the Caribbean Aircrew Archive is a permanent record of West Indian volunteers who served in the RAF but whose contribution has since been overlooked.[7] It is the collaboration of Grant and Hans Klootwijk, author of Lancaster W4827: Failed to Return, which recounts the fate of Grant and his fellow airmen after their plane was shot down over the Netherlands in 1943. The book is based on research carried out by Klootwijk's father, Joost Klootwijk, who was 11 when the bomber crashed into a farmhouse in his village.[48][49]

With regular updates by surviving aircrew and relatives, as well as by military historians, the online archive has established that West Indians who served as aircrew in the RAF numbered roughly 440 and that at least 70 were commissioned and 103 decorated.

Writings

[edit]- Ring of Steel: Pan Sound and Symbol — discusses the history, science and musicology of the steelpan. Macmillan Caribbean, 1999, ISBN 978-0333661284.

- A Member of the Royal Air Force of Indeterminate Race, published by Woodfield Publishing in 2006, takes its title from the translation of a caption that appeared underneath Grant's photograph in a German newspaper after his detention as a POW.[50]

- Rivers of Time: Collected Poems of Cy Grant — documents Grant's poetical journey through life and considers the influences that have contributed to his understanding of himself and the world. Naked Light, 2008, ISBN 978-0955217821.

- Some of the 88 poems have appeared in earlier collections, including Blue Foot Traveler: an Anthology of West Indian Poets in Britain edited by Jamaican author James Berry (1976) and Caribbean Voices, Volume 2: The Blue Horizons edited by John Figueroa (1970).

- Blackness & the Dreaming Soul – A Sense of Belonging: Multiculturalism and the Western Paradigm. Shoving Leopard. 2007. ISBN 978-1-905565-08-5. A mixture of autobiography, cultural study and philosophical exposition, the book tells the story of Grant's journey of self-discovery and the major influences upon it. It is a critique of the perceived dualistic nature of Western culture that has resulted in the "alienation" of humans from both nature and themselves.[51]

- Our Time Is Now: Six Essays on the Need for Re-Awakening — a collection of essays. Cane Arrow Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0956290120.[52]

Stage, film and television credits

[edit]- Member of Laurence Olivier's Festival of Britain Company, London and New York City (1951–52),[53] in Anthony and Cleopatra and Caesar and Cleopatra[54]

- Safari (1955) – Chief Massai

- Man From The Sun (TV, 1956)

- Sea Wife (1957) – "Number 4"

- Home of the Brave (TV, 1957)

- Tonight (TV, 1957–60)

- Calypso (1958)

- The Encyclopædist (TV, 1961)

- Freedom Road: Songs of Negro Protest (TV, 1964)

- Othello – Othello (Phoenix Theatre, Leicester, 1965)

- Cindy Ella (Garrick Theatre, London, 1966)

- Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons – Lieutenant Green (TV, 1967–68)

- Doppelganger - Doctor Gordon (1969)

- The Persuaders! (TV, one episode, 1971)

- Shaft in Africa (1973) – Emir Ramila

- Softly, Softly: Taskforce (TV, one episode, 1974)

- The Iceman Cometh (Royal Shakespeare Company, 1976)

- At the Earth's Core (1976) – Ra

- Return to My Native Land (Royal National Theatre and Royal Court Theatre; national tour; 1977–79)[29][28]

- Blake's 7 (TV, 1980)

- Night and Day (Derby Playhouse, 1981)

- Metal Mickey (TV, 1981–82) – Mr Young

- Maskarade by Sylvia Wynter (Talawa Theatre Company at Cochrane Theatre, London, 1994)[55]

References

[edit]- ^ "Cy Grant: Actor, Singer and Writer", The Times (London), 16 February 2010.

- ^ a b Gus John, "Cy Grant obituary", The Guardian (London), 18 February 2010.

- ^ a b Kurt Barling, "Cy Grant: Pioneer for black British actors" (obituary), The Independent (London), 27 February 2010.

- ^ "About Cy Grant". the Cy Grant Website. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ a b John Moat. "Didymus – Millennium Celebration". Resurgence. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d Angela Cobbinah, "Archive launched in recognition of black activist Cy Grant" Archived 14 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Camden Review, 18 August 2016.

- ^ a b "Caribbean aircrew in the RAF during WW2" website.

- ^ a b "DIDI'S STORY: In loving memory of Cy's wife Dorit Grant 08/07/1927 – 28/04/2018", Cy Grant website, 8 May 2018.

- ^ Vinette K. Price, "Britain lauds Grant, a trailblazing Guyanese", Caribbean Life, 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Cy Grant (2007). Blackness & the Dreaming Soul – A Sense of Belonging: Multiculturalism & the Western Paradigm. Shoving Leopard. pp. 3–14. ISBN 978-1-905565-08-5.

- ^ Stephen Bourne, "Cy Grant — Into the Wind", in The Motherland Calls: Britain's Black Servicemen & Women, 1939–45, The History Press, 2012, quoting Jim Pines (ed.), Black and White in Colour: Black People in British Television Since 1936 (BFI Publishing, 1992), pp. 43–44.

- ^ "Philosopher Flight Lieutenant Cy Grant". Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ "Veterans remember Germany bombing raids". The Daily Telegraph. 9 March 2008.

- ^ Alec Lom, "The men of bomber command: the navigator, Cy Grant", The Telegraph, 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Moving Here: Stories: Cy Grant from Guyana". movinghere.org.uk. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- ^ Kurt Barling, "Remembering Cy Grant", Barling's London, BBC News, 28 February 2010.

- ^ Kurt Barling, "Failed to Return", BBC London, 28 October 2014.

- ^ "Into the Wind: The story of Bomber Command", BBC Lincolnshire, 19 April 2010.

- ^ a b c Black History| issue=365 Archived 29 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Spring/Summer 2009, Interview with Cy Grant by Angela Cobbinah.

- ^ Angela Cobbinah, "Novelist Jan Carew – The Soldier Savant", 30 July 2009.

- ^ a b c Gus John, "Obituary: Cy Grant, November 8, 1919 – February 13, 2010", Stabroek News, 28 February 2010.

- ^ Lloyd Bradley, Sounds Like London: 100 Years of Black Music in the Capital, London: Serpent's Tail/Profile Books, 2013, p. 55.

- ^ "Man From The Sun, A (1956)", BFI Screenonline.

- ^ Music at cygrant.com.

- ^ Colin Chambers, "Black British Plays Post World War II -1970s", Black Plays Archive, National Theatre.

- ^ Angela Cobbinah, "Feature: Obituary - Death of cultural activist and 1960s calypso singer Cy Grant" Archived 11 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Islington Tribune, 18 February 2010.

- ^ Professor Gus John and Dr Samina Zahir, Speaking Truth to Power: a Diversity of Voices in Theatre and the Arts in England Archived 10 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Arts Council England, July 2008, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b "Return to my Native Land", the Cy Grant Website.

- ^ a b "Return To My Native Land", at Black Plays Archive, National Theatre.

- ^ Kurt Barling, "London, sugar and slavery", Abolition, BBC, London, 24 September 2014.

- ^ Honorary Fellowships Archived 15 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine of the University of Surrey Roehampton.

- ^ "Cy Grant" (obituary), The Daily Telegraph (London), 15 February 2010.

- ^ Alleyne, Oluatoyin (17 December 2017). "A glimpse at the life of Cy Grant - icon immortalized as body of work archived". Stabroek News.

- ^ a b "'Failed to Return' Airman Honoured", Royal Air Force, 12 March 2010.

- ^ "Caribbean Glory" Archived 23 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Andrews Air Force Base Officers Club, 19 June 2009.

- ^ "Cy Grant Day at the BFI: Tribute to a Hero", Black History Walks (Inspirational & Educational Events archive).

- ^ Sean Creighton, "Life and Times of Cy Grant", History & Social Action News and Events, 12 November 2016.

- ^ "Guyanese Actor Cy Grant To Be Honoured With Blue Plaque", The Voice, 8 November 2017.

- ^ Jon King, "Life and work of black theatre pioneer Cy Grant to be marked with blue plaque at icon's Highgate home", Ham & High, 10 November 2017.

- ^ "Plaque: Cy Grant". London Remembers. November 2017.

- ^ "Cy Grant - Celebrating the life and times of Cy Grant". Cy Grant. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ "Cy Grant - Navigating the dreams of an icon through his archive" Archived 12 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, London Metropolitan Archives at The City of London, 12 May 2016.

- ^ "City of London's archives pay tribute to Caribbean hero"[permanent dead link], Caribbean 360, 4 May 2016 (via A Taste of Guyana).

- ^ "Celebrating the Life of Cy Grant – Touring Exhibition", Marcus Garvey Library, Tottenham Green Leisure Centre, 1–30 November 2016.

- ^ Nicole-Rachelle Moore, "Cy Grant, Guyanese Everyman - To Be Celebrated by London Metropolitan Archives", Soca News, 13 February 2017.

- ^ "Work of Guyanese icon Cy Grant celebrated", Stabroek News, 18 February 2017.

- ^ "Caribbean Air Crew archive ww2", itzcaribbean, 18 December 2009.

- ^ "Flyers of the Caribbean". BBC Online: London. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "People Profile: Flight Lieutenant Cy Grant" (PDF). Commonwealth Veterans. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ Cy Grant (2010). A Member of the RAF of Indeterminate Race: World War Two experiences of a West Indian Officer in the RAF. Woodfield Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84683-018-1.

- ^ "Blackness and the Dreaming Soul: A journey of self discovery by Cy Grant". Archived from the original on 7 December 2004. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). - ^ Angela Cobbinah (11 February 2010). "Book Review: Our Time Is Now: Six Essays on the Need for Re-Awakening". Islington Tribune. Archived from the original on 18 February 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ CV, Cy Grant's Blog Spot.

- ^ "Calypso Singer Cy Grant Scores In London", Jet, 26 March 1953, p. 55.

- ^ "Maskarade", Black Plays Archive, National Theatre.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Cy Grant at IMDb

- Cy Grant discography at Discogs

- Cy Grant on Blogger

- Vibert Cambridge, "Cy Grant: Doing it his way", Stabroek News, 18 April 2004, via Guyana: Land of Six Peoples.

- "GRANT – Cy", Caribbean Aircrew in the RAF during WW2 website.

- Gus John, Tribute to Cy Grant at BFI, 7 November 2010.

- "People Profile: Flight Lieutenant Cy Grant", Commonwealth Veterans.

- Cy Grant at National Portrait Gallery, London

- 1919 births

- 2010 deaths

- 20th-century Guyanese male actors

- 20th-century Guyanese male singers

- 20th-century Guyanese writers

- 20th-century memoirists

- 21st-century essayists

- 21st-century Guyanese writers

- Black British television personalities

- British Guiana people

- Calypsonians

- English people of Antigua and Barbuda descent

- Folk guitarists

- Guyanese activists

- Guyanese emigrants to the United Kingdom

- Guyanese essayists

- Guyanese military personnel

- Guyanese people of Antigua and Barbuda descent

- Guyanese people of World War II

- 20th-century Guyanese poets

- Guyanese poets

- Guyanese radio presenters

- Male essayists

- Male singer-songwriters

- Members of the Middle Temple

- Music historians

- People associated with the University of Roehampton

- People from Demerara-Mahaica

- Actors from the London Borough of Camden

- People from Highgate

- People from New Amsterdam, Guyana

- Royal Air Force officers

- Royal Air Force personnel of World War II

- Royal Shakespeare Company members

- Stalag Luft III prisoners of World War II

- Steelpan musicians