Tea Act

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2018) |

| |

| Long title | An act to allow a drawback of the duties of customs on the exportation of tea or oil to any of his Majesty's colonies or plantations or farms in America; to increase the deposit on bohea tea to be sold at the East India Company's sales, and to empower the commissioners of the treasury to grant licenses to the East India Company to export tea duty-free. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 13 Geo. 3. c. 44 |

| Introduced by | The Rt. Hon. Lord North, KG, MP Prime Minister, Chancellor of the Exchequer & Leader of the House of Commons |

| Territorial extent | |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 10 May 1773 |

| Commencement | 10 May 1773 |

| Repealed | 6 August 1861 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | Statute Law Revision Act 1861 |

| Relates to | |

Status: Repealed | |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

| Part of a series on the |

| American Revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

The Tea Act 1773 (13 Geo. 3. c. 44) was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain. The principal objective was to reduce the massive amount of tea held by the financially troubled British East India Company in its London warehouses and to help the struggling company survive.[1] A related objective was to undercut the price of illegal tea, smuggled into Britain's North American colonies. This was supposed to convince the colonists to purchase Company tea on which the Townshend duties were paid, thus implicitly agreeing to accept Parliament's right of taxation. Smuggled tea was a large issue for Britain and the East India Company, since approximately 86% of all the tea in America at the time was smuggled Dutch tea.

The Act granted the Company the right to directly ship its tea to North America and the right to the duty-free export of tea from Britain, although the tax imposed by the Townshend Acts and collected in the colonies remained in force. It received the royal assent on May 10, 1773.

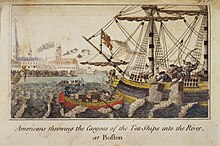

Colonists in the Thirteen Colonies recognized the implications of the Act's provisions, and a coalition of merchants, smugglers, and artisans similar to that which had opposed the Stamp Act 1765 mobilized opposition to the delivery and distribution of the tea. The company's authorised consignees were harassed, and in many colonies, successful efforts were made to prevent the tea from being landed. In Boston, this resistance culminated in the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773, when colonists (some disguised as Native Americans) boarded tea ships anchored in the harbour and dumped their tea cargo overboard. Parliamentary reaction to this event included the passage of the Coercive Acts, designed to punish Massachusetts for its resistance, and the appointment of General Thomas Gage as royal governor of Massachusetts. These actions further raised tensions that led to the eruption of the American War of Independence in April 1775.

Parliament passed the Taxation of Colonies Act 1778, which repealed a number of taxes (including the tea tax that underlay this act) as one of a number of conciliatory proposals presented to the Second Continental Congress by the Carlisle Peace Commission. The commission's proposals were rejected. The Act effectively became a "dead letter", but was not formally removed from the books until the passage of the Statute Law Revision Act 1861.

Background

[edit]In the 1760s and earlier the East India Company had been required to sell its tea exclusively in London on which it paid a duty which averaged two shillings and six pence per pound.[2] Tea destined for the North American colonies would be purchased by merchants specializing in that trade, who transported it to North America for eventual retail sale. The markups imposed by these merchants, combined with the tea tax imposed by the Townshend Acts of 1767 created a profitable opportunity for American merchants to import and distribute tea purchased from the Dutch in transactions and shipments that violated the Navigation Acts and were treated by British authorities as smuggling. Smugglers imported some 900,000 pounds (410,000 kg) of cheap foreign tea per year. The quality of the smuggled tea did not match the quality of the dutiable East India Company tea, of which the Americans bought 562,000 pounds (255,000 kg) per year.[3] Although the British tea was more appealing in flavor, some Patriots like the Sons of Liberty encouraged the consumption of smuggled tea as a political protest against the Townshend taxes.

In 1770 most of the Townshend taxes were repealed, but taxes on tea were retained. Resistance to this tax included pressure to avoid legally imported tea, leading to a drop in colonial demand for the Company's tea and a burgeoning surplus of the tea in the company's English warehouses. By 1773 the Company was close to collapse due in part to contractual payments to the British government of £400,000 per year, together with war and a severe famine in Bengal which drastically reduced the Company's revenue from India, and economic weakness in European markets. Benjamin Franklin was one of several people who suggested things would be greatly improved if the Company was allowed to export its tea directly to the colonies without paying the taxes it was paying in London: "to export such tea to any of the British colonies or plantations in America, or to foreign parts, import duty of three pence a pound."[2]

The administration of Lord North saw an opportunity to achieve several goals with a single bill. If the Company was permitted to directly ship tea to the colonies, this would remove the markups of the middlemen from the cost of its tea. Reducing or eliminating the duties paid when the tea was landed in Britain (if it was shipped onward to the colonies) would further lower the final cost of tea in the colonies, undercutting the prices charged for smuggled tea. Colonists would willingly pay for cheaper Company tea, on which the Townshend tax was still collected, thus legitimizing Parliament's ability to tax the colonies.

Provisions of the Act

[edit]The Act, which received the royal assent on May 10, 1773, contained the following provisions:

- The Company was eligible to be granted a license to export tea to North America.

- The Company was no longer required to sell its tea at the London Tea Auction.

- Duties on tea (charged in Britain) destined for North America "and foreign parts" would either be refunded on export or not imposed.

- Consignees receiving the Company's tea were required to pay a deposit upon receipt of tea.

Proposals were made that the Townshend tax also is waived, but North opposed this idea, citing the fact that those revenues were used to pay the salaries of crown officials in the colonies.

Implementation

[edit]The Company was granted a license by the North administration to ship tea to major American ports, including Charleston, Philadelphia, New York City, and Boston. Consignees who were to receive the tea and arrange for its local resale were generally favorites of the local governor (who was royally appointed in South Carolina, New York, and Massachusetts, and appointed by the proprietors in Pennsylvania). In Massachusetts, Governor Thomas Hutchinson was a part-owner of the business hired by the Company to receive tea shipped to Boston.

Reaction

[edit]

Many colonists opposed the Act, not so much because it rescued the East India Company, but more because it seemed to validate the Townshend Tax on tea. Merchants who had been acting as the middlemen in legally importing tea stood to lose their business, as did those whose illegal Dutch trade would be undercut by the Company's lowered prices. These interests combined forces, citing the taxes and the Company's monopoly status as reasons to oppose the Act.

In New York and Philadelphia, opposition to the Act resulted in the return of tea delivered there back to Britain. In Charleston, the colonists left the tea on the docks to rot. Governor Hutchinson in Boston was determined to leave the ships in port, even though vigilant colonists refused to allow the tea to be landed.[4] Matters reached a crisis when the time period for landing the tea and paying the Townshend taxes was set to expire, and on December 16, 1773, colonists disguised as Indians swarmed aboard three tea-laden ships and dumped their cargo into the harbour in what is now known as the Boston Tea Party. Similar "Destruction of the Tea" (as it was called at the time) occurred in New York and other ports shortly thereafter, though Boston took the brunt of Imperial retaliation because it was the first "culprit".

Consequences

[edit]The Boston Tea Party appalled British political opinion makers of all stripes. The action united all parties in Britain against the American radicals. Parliament enacted the Boston Port Act, which closed Boston Harbor until the dumped tea was paid for. This was the first of the so-called Coercive Acts, or Intolerable Acts as they were called by the colonists, passed by Parliament in response to the Boston Tea Party. These harsh measures united many colonists even more in their frustrations against Britain and were one of the many causes of the American Revolutionary War.

The Taxation of Colonies Act 1778 repealed the tea tax and others that had been imposed on the colonies, but it proved insufficient to end the war. The Tea Act became a "dead letter" as far as the Thirteen Colonies were concerned, and was formally removed from the books in 1861. This would go against their belief that only colonial governments could tax the colonies. Some American colonists became very frustrated. Ships carrying the company’s tea arrived in Philadelphia and New York but chose to return to England without unloading rather than face angry mobs. C

Ãæ⟨⟩

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Tea Act | Great Britain [1773]".

- ^ a b Ketchum, pg. 240

- ^ Unger, pg. 148

- ^ "The Tea Act". ushistory.org. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

References

[edit]- Ketchum, Richard, Divided Loyalties, How the American Revolution came to New York, 2002, ISBN 0-8050-6120-7

- Unger, Harlow, John Hancock, Merchant King and American Patriot, 200, ISBN 0-7858-2026-4