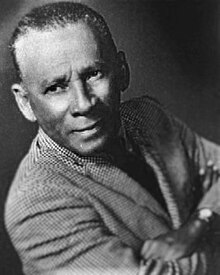

Rafael Hernández Marín

Rafael Hernández | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Rafael Hernández Marín |

| Born | October 24, 1892 Aguadilla, Captaincy General of Puerto Rico |

| Died | December 11, 1965 (aged 73) San Juan, Puerto Rico |

| Genres | Canción, bolero, guaracha, lamento |

| Occupation | Composer |

| Formerly of | |

Rafael Hernández Marín (October 24, 1892 – December 11, 1965) was a Puerto Rican songwriter and the author of hundreds of popular songs in the Latin American repertoire.[1] He specialized in Cuban styles, such as the canción, bolero and guaracha. Among his most famous compositions are "Lamento Borincano,” "Capullito de alhelí,” "Campanitas de cristal,” "Cachita,” "Silencio,” "El cumbanchero,” "Ausencia,” and "Perfume de gardenias.”

Career

[edit]Early years

[edit]Rafael Hernández Marín was born in the town of Aguadilla, Puerto Rico, into a poor family, on October 24, 1892. His parents were María Hernández Marín and Miguel Angel Rosa, though he was given only his mother's surname.[2][3] As a child, he learned the craft of cigar making, from which he made a modest living. He also grew to love music and asked his parents to permit him to become a full-time music student. When he was 12 years old, Hernández studied music in San Juan, under the guidance of music professors Jose Ruellan Lequenica and Jesús Figueroa. He learned to play many musical instruments, including the clarinet, tuba, violin, piano, and guitar.[4] At 14, he played for the Cocolia Orquestra. Hernández moved to San Juan where he played for the municipal orchestra under the director Manuel Tizol. In 1913, Hernández begot his first child, Antonio Hernández (out of wedlock), to Ana Bone.

World War I and the Orchestra Europe

[edit]

In 1917, Hernández was working as a musician in North Carolina, when the United States entered World War I. The jazz bandleader, James Reese Europe, recruited brothers Rafael and Jesús Hernández, along with 16 more Puerto Ricans, to join the United States Army's Harlem Hell fighters musical band, the Orchestra Europe. He enlisted and was assigned to the U.S. 369th Infantry Regiment (formerly known as the 15th Infantry Regiment, New York National Guard, created in New York City June 2, 1913). The regiment, nicknamed "The Harlem Hell Fighters,” by the Germans, served in France. Hernández toured Europe with the Orchestra Europe. The 369th was awarded the French Croix de Guerre for battlefield gallantry by the President of France.[5]

Hernandez and Pedro Flores, Life in Cuba and Mexico

[edit]After World War I ended, he returned to the United States in 1919. Hernández began a long and intense period of artistic composition and performance. He was part of the Lucky Roberts Band, with which he made his first musical tour of the United States. Later, he moved to Cuba, where he directed the Fausto Theater orchestra in Havana.[6] Later on, Hernández moved to New York City. In 1925,[6] he started writing songs and organized a trio called "Trio Borincano.” In 1926, fellow Puerto Rican Pedro Flores, who was a composer, joined the Trio. Even though Hernández and Flores became and always remained good friends, they soon went their separate ways and artistically competed against each other. After the trio broke up, he formed a quartet called "Cuarteto Victoria," which included singer Myrta Silva, also known as La Guarachera and La Gorda de Oro. With both groups, Hernández traveled and played his music all over the United States and Latin America.[7] On September 2, 1927, Hernández's sister, Victoria, opened Casa Hernandez, a music store which also acted as a booking agency and base of operations for her brother.[5] In 1929, Trío Borinquen recorded Linda Quisqueya (originally titled Linda Borinquen) and that same year, he founded the "Cuarteto Victoria" (also known as "El Cuarteto Rico") named after his sister.[5]

In 1932, Hernández moved to Mexico. There, he directed an orchestra and enrolled in Mexico's National Music Conservatory, to further enrich his musical knowledge. Hernández also became an actor and organized musical scores in Mexico's "golden age" of movies. His wife (and eventual widow) is Mexican.[8]

"Lamento borincano" and "Preciosa"

[edit]In 1937, Hernández wrote "Lamento Borincano.” That same year, he also wrote "Preciosa.” In 1947, Hernández returned to Puerto Rico and became the director of the orchestra at the government-owned WIPR Radio.[7]

Hernandez also composed Christmas music, Danzas, Zarzuelas, Guarachas, Lullabies, Boleros, Waltzes, and more.[7]

Hernández's works include "Ahora seremos felices" (Now, We Will Be Happy), "Campanitas de cristal" (Crystal Bells), "Capullito de Alhelí,” "Culpable" (Guilty), "El Cumbanchero"[9] (also known as "Rockfort Rock" or "Comanchero" (sic) to reggae aficionados), "Ese soy yo" (That's Me), "Perfume de Gardenias" (Gardenia's Perfume), "Silencio" (Silence), and "Tú no comprendes" (You Don't Understand), among 3,000 others. Many of his compositions were strongly based on Cuban musical idioms, such as the guaracha's "Cachita" and "Buchipluma na' ma,” which were often mistaken as songs by Cuban authors.[10] His music became an important part of Puerto Rican culture.[8]

Later years and death

[edit]Hernández was Honorary President of the Authors and Composers Association. He was also the founder of little league baseball in Puerto Rico. President John F. Kennedy christened him "Mr. Cumbanchero".[4]

Hernández died in San Juan on December 11, 1965, shortly after Banco Popular de Puerto Rico produced a TV special in his honor in which he addressed the people for the last time. The special was simulcast on all TV and most island radio stations. The TV special was rebroadcast on May 13, 2007. Rafael Hernández's remains are buried in the Santa María Magdalena de Pazzis Cemetery of Old San Juan.

Legacy

[edit]Puerto Rico has honored his memory by naming public buildings, avenues, and schools after him. The airport in Aguadilla is named Rafael Hernández Airport. There are schools in New York City, Boston, and in Newark, New Jersey named after Rafael Hernández. Renowned Puerto Rican sculptor Tomás Batista created a statue of Hernández, which is in the municipality of Bayamón, Puerto Rico. The Interamerican University of Puerto Rico, the repository of his works, operates a small museum in his honor at its Metropolitan Campus in San Juan, which is directed by his son, Alejandro (Chalí) Hernández. The Hernandez Houses housing complex in New York City is named after Rafael Hernández.

At the behest former senator Lucy Arce, the Senate of Puerto Rico, under the first term of Thomas Rivera Schatz built the Rafael Hernández Plaza with a bigger-than-lifesize statue of the composer, and a statue of a Puerto Rican jíbaro riding a horse honoring his Lamento Borincano. The park is located at the easternmost tip of San Juan's Paseo de la Covadonga.

Puerto Rican singer Marc Anthony recorded Hernández's "Preciosa" and sang the song in a 2005 concert in New York City's Madison Square Garden. According to an article in the New York Times:

"Mr. Anthony did his version of Preciosa. It may have been the night's most popular love song, precisely because it's not about a woman: it's about a whole island, instead."[11]

In 1969, Puerto Rican actor Orlando Rodriguez played Hernandez in the bio-pic El Jibarito Rafael, which was directed by the Mexican actor Julián Soler.[12]

In 1999, Hernández was posthumously inducted into the International Latin Music Hall of Fame.[13]

On March 23, 2001, Casa Hernandez, the music store which served as Hernandez's booking agency and base of operations, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places, reference #01000244, as "Casa Amadeo, antigua Casa Hernandez".[14]

In 2017, Rafael Hernández was posthumously inducted to the Puerto Rico Veterans Hall of Fame.[15]

Military decorations and awards

[edit]Among Hernández's military decorations are the following:

See also

[edit]- African immigration to Puerto Rico

- List of Puerto Ricans

- Puerto Ricans in World War I

- Puerto Rican songwriters

References

[edit]- ^ Music of Puerto Rico

- ^ Gates, Henry Louis Jr.; Brooks-Higginbotham, Evelyn, eds. (2008). The African American National Biography. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-195-16019-2.

He was one of four children of Miguel Angel Rosa and Maria Hernandez. (There is no information regarding the reason why he was given only his mother's last name.)

- ^ "1910 U. S. Federal Census, Tamarindo, Aguadilla, Puerto Rico". FamilySearch (in Spanish). Washington, D. C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. 21 April 1910. pp. 10A–10B. NARA microfilm publication T624, roll #1757, page 10A lines 23-25 and on page 10B lines 26-27. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ a b Rafael Hernandez Puerto Rico's Soul

- ^ a b c - The Great Slsa Timeline

- ^ a b "Rafael Hernández-Marín".

- ^ a b c Hernandez Marin, Rafael

- ^ a b History of Puerto Rico

- ^ Berenguer González, Ramón T. "El Cumbanchero" Salsa Mp3· ISWC T-0425394622 Published with the permission of the owner of the version

- ^ González, Reynaldo (2000). "Yo soy del son a la salsa". Cinémas d'Amérique Latine (in Spanish and French) (8): 79.

- ^ Klefa Sanneh Latin Singers who Offer 3 Varieties of Heartthrob New York Times, September 12, 2005

- ^ El Jibarito Rafael at IMDb

- ^ de Fontenay, Sounni (7 December 1998). "International Latin Music Hall of Fame". Latin American Rhythm Magazine. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ Howe, Kathleen A. (November 2000). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Casa Amadeo, antigua Casa Hernandez". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2011-01-12. See also: "Accompanying 10 photos".

- ^ "Salón de la Fama".

External links

[edit]- 1892 births

- 1965 deaths

- Burials at Santa María Magdalena de Pazzis Cemetery

- 20th-century Puerto Rican musicians

- Puerto Rican composers

- Puerto Rican male composers

- Puerto Rican Army personnel

- United States Army personnel of World War I

- United States Army soldiers

- People from Aguadilla, Puerto Rico

- American recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France)

- Guaracha songwriters

- 20th-century American composers

- 20th-century American male musicians