Culture of Mexico

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2022) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Mexico |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Topics |

| Symbols |

Mexico's culture emerged from the culture of the Spanish Empire and the preexisting indigenous cultures of Mexico. Mexican culture is described as the 'child' of both western and native American civilizations. Other minor influences include those from other regions of Europe, Africa and also Asia.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

First inhabited more than 10,000 years ago, the cultures that developed in Mexico became one of the cradles of civilization. During the 300-year rule by the Spanish, Mexico was a crossroads for the people and cultures of Europe and America, with minor influences from West Africa and parts of Asia. Starting in the late 19th century, the government of independent Mexico has actively promoted cultural fusion (mestizaje) and shared cultural traits in order to create a national identity. Despite this base layer of shared Mexican identity and wider Latin American culture, the big and varied geography of Mexico and the many different indigenous cultures create more of a cultural mosaic, comparable to the heterogeneity of countries like India or China.

From the pyramids of Teotihuacan to the intricate murals of Diego Rivera and the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Cuisine delights with its fusion of indigenous ingredients like maize and chili peppers, showcased in beloved dishes such as tacos and mole. Festivals like Dia de los Muertos celebrate indigenous traditions alongside Catholic rituals, while music genres like mariachi, popular music and regional dances like ballet folklórico express cultural diversity and pride. Luminaries like Octavio Paz and Carlos Fuentes contributing to a global literary canon. Sports, particularly soccer, unify the nation in fervent support, alongside the enduring influence of telenovelas and iconic figures like Thalía and a deep-rooted sense of community and family.

The culture of an individual Mexican is influenced by familial ties, gender, religion, location, and social class, among other factors. Contemporary life in the cities of Mexico has become similar to that in the neighboring United States and in Europe, with provincial people conserving traditions more than city dwellers.[7]

Religion

[edit]

The Spanish arrival and colonization brought Roman Catholicism to the country, which became the main religion of Mexico. Mexico is a secular state, and the Constitution of 1917 and anti-clerical law imposed limitations on the church and sometimes codified state intrusion into church matters. The government does not provide any financial contributions to the church, and the church does not participate in public education.[8][9]

In 2010, 95.6% of the population were Christian.[10] Roman Catholics are 89%[11] of the total, 47% percent of whom attend church services weekly.[12] In absolute terms, Mexico has the world's second largest number of Catholics after Brazil.[13] According to the Government's 2000 census, approximately 87 percent of respondents identified themselves as at least nominally Roman Catholic. Christmas is a national holiday and every year during Easter and Christmas all schools in Mexico, public and private, send their students on vacation.

Other religious groups for which the 2000 census provided estimates included evangelicals, with 1.71 percent of the population; other Protestant evangelical groups, 2.79 percent; members of Jehovah's Witnesses, 1.25 percent; "Historical" Protestants, 0.71 percent; Seventh-day Adventists, 0.58 percent; The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 0.25 percent; Jews, 0.05 percent; and other religions, 0.31 percent. Approximately 3.52 percent of respondents indicated no religion, and 0.86 percent did not specify a religion.

Arts

[edit]

Mexico is known for its folk art traditions, mostly derived from the indigenous and Spanish crafts.[14] Pre-Columbian art thrived over a wide timescale, from 1800 BC to AD 1500. Certain artistic characteristics were repeated throughout the region, namely a preference for angular, linear patterns, and three-dimensional ceramics.

Notable handicrafts include clay pottery from the valley of Oaxaca and the village of Tonala. Colorfully embroidered cotton garments, cotton or wool shawls and outer garments, and colorful baskets and rugs are seen everywhere. Mexico is also known for its pre-Columbian architecture, especially for public, ceremonial and urban monumental buildings and structures.

Following the conquest, the first artistic efforts were directed at evangelization and the related task of building churches. The Spanish initially co-opted many indigenous stonemasons and sculptors to build churches, monuments and other religious art, such as altars. The prevailing style during this era was Baroque. In the period from independence to the early 20th century, Mexican fine arts continued to be largely influenced by European traditions.

After the Mexican Revolution, a new generation of Mexican artists led a vibrant national movement that incorporated political, historic and folk themes in their work. The painters Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Siqueiros were the main propagators of Mexican muralism. Their grand murals often displayed on public buildings, promoted social ideals. Rufino Tamayo and Frida Kahlo produced more personal works with abstract elements. Mexican art photography was largely fostered by the work of Manuel Álvarez Bravo.[15]

-

Murals of Bonampak (between 580 and 800 AD)

-

La huida a Egipto (The Flight into Egypt). Miguel Cabrera, around 1700.

-

Exconvento (Ex-convent), by José María Velasco. 1860.

-

La leyenda de los volcanes (The legend of the volcanoes). Saturnino Herrán. 1910–1912.

-

Liberación (Liberation). Jorge González Camarena. 1908.

Literature

[edit]

Mexican literature has its antecedents in the literature of the indigenous settlements of Mesoamerica and European literature.[16] The most well known pre-Hispanic poet is Netzahualcoyotl. Modern Mexican literature is influenced by the concepts of the Spanish colonialization of Mesoamerica. Outstanding colonial writers and poets include Juan Ruiz de Alarcón and Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

Other notable writers include Alfonso Reyes, José Joaquín Fernández de Lizardi, Ignacio Manuel Altamirano, Maruxa Vilalta, Carlos Fuentes, Octavio Paz (Nobel Laureate), Renato Leduc, Mariano Azuela ("Los de abajo"), Juan Rulfo ("Pedro Páramo"), Juan José Arreola, and Bruno Traven.

Contemporary Mexican literature not only captures the essence of Mexican culture but also resonates with universal themes, making it a significant contribution to world literature. Authors like Elena Poniatowska, Juan Villoro, Valeria Luiselli, Yuri Herrera, and Fernanda Melchor delve into themes such as migration, inequality, historical memory, and the complexities of Mexican society.

Language

[edit]

Mexico is the most populous Spanish-speaking country in the world.[17] Although the overwhelming majority of Mexicans today speak Spanish, there is no de jure official language at the federal level. The government recognizes 62 indigenous Amerindian languages as national languages.[18]

Some Spanish vocabulary in Mexico has roots in the country's indigenous languages, which are spoken by approximately 6% of the population.[18] Some indigenous Mexican words have become common in other languages, such as the English language. For instance, the words tomato, chocolate, coyote, and avocado are Nahuatl in origin.[19]

Architecture

[edit]

With thirty-four sites, Mexico has more sites on the UNESCO World Heritage list than any other country in the Americas; most of the sites pertain to Mexico's architectural history. Mesoamerican architecture in Mexico is best known for its public, ceremonial, and urban monumental buildings and structures, several of which are the largest monuments in the world. Mesoamerican architecture is divided into three eras, Pre-Classic, Classic, and Post-Classic. Architect Frank Lloyd Wright is reputed to have declared the Puuc-style architecture of the Maya as the best in the Western Hemisphere.[20]

The New Spanish Baroque dominated in early colonial Mexico. During the late 17th century to 1750, one of Mexico's most popular architectural styles was Mexican Churrigueresque, which combined Amerindian and Moorish decorative influences.[21]

The Academy of San Carlos, founded in 1788, was the first major art academy in the Americas. The academy promoted Neoclassicism, focusing on Greek and Roman art and architecture. Notable Neoclassical works include the Hospicio Cabañas, a world heritage site, and the Palacio de Minería, both by Spanish Mexican architect Manuel Tolsá.

From 1864 to 1867, during the Second Mexican Empire, Maximilian I was installed as emperor of Mexico. His architectural legacy lies in the redesigning of the Castillo de Chapultepec and creating the Paseo de la Reforma. This intervention, financed largely by France, was brief, but it began a period of French influence in architecture and culture. The style was emphasized during the presidency of Porfirio Diaz, who was a pronounced francophile. Notable works from the Porfiriato include the Palacio de Correos and a large network of railways.

After the Mexican Revolution in 1917, idealization of the indigenous and the traditional symbolized attempts to reach into the past and retrieve what had been lost in the race toward modernization.

Functionalism, expressionism, and other schools left their imprint on a large number of works in which Mexican stylistic elements have been combined with European and American techniques, most notably the work of Pritzker Prize winner Luis Barragán. His personal home, the Luis Barragán House and Studio, is a World Heritage Site.

Enrique Norten, the founder of TEN Arquitectos, has been awarded several honors for his work in modern architecture. His work expresses a modernity that reinforces the government's desire to present a new image of Mexico as an industrialized country with a global presence.

Other notable and emerging contemporary architects include Mario Schjetnan, Michel Rojkind, Isaac Broid Zajman, Bernardo Gómez-Pimienta, and Alberto Kalach.

-

Ancient city of Teotihuacán (200 BC - 800 AD).

-

Ancient Mayan city of Uxmal, exuberant in Puuc style. ~700 AD.

-

Church of Santo Domingo de Guzmán, Oaxaca. 1572–1724

-

Cathedral of Zacatecas. 1729–1772.

-

Casa del alfeñique (House of the alfeñique), Puebla. Late 1700s.

-

Hospicio Cabañas. 1791

-

Juárez Theater, Guanajuato. 1873–1903

-

Quinta Gameros, Chihuahua. 1910.

-

Palacio de Bellas Artes (Palace of Fine Arts). 1904–1934.

Cinema

[edit]

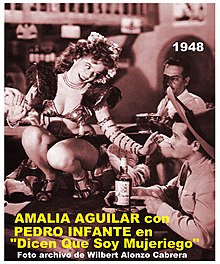

The history of Mexican cinema dates to the beginning of the 20th century when several enthusiasts of the new medium documented historical events – most particularly the Mexican Revolution. Mexican cinema began in the late 19th century with the introduction of film technology. The first Mexican film is considered to be "Don Juan Tenorio" (1898) by Salvador Toscano Barragán. The Golden Age of Mexican cinema is the name given to the period between 1935 and 1959, where the quality and economic success of the cinema of Mexico reached its peak. Directors like Emilio Fernández ("Maria Candelaria"), Fernando de Fuentes ("Vámonos con Pancho Villa"), and Julio Bracho ("Distinto Amanecer") were prominent figures. An era when renowned actors such as Cantinflas and Pedro Infante appeared on the silver screen. Actresses such as Dolores del Río and María Félix became icons of Mexican cinema during this era.[22]

The emergence of the "Nuevo Cine Mexicano" in the late 20th century introduced new talents like Arturo Ripstein ("El Castillo de la Pureza") and Felipe Cazals ("Canoa"). In the renaissance and New Wave of the 1960s-1970s. Present-day film makers from 1980s-Present, include directors like Alfonso Cuarón ("Y Tu Mamá También"), Guillermo del Toro ("Pan's Labyrinth"), and Alejandro González Iñárritu ("Amores Perros) gained international acclaim, contributing to a resurgence in Mexican cinema's global influence. Other influential individuals include Carlos Reygadas (Stellet Licht), screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga and directors of photography such as Guillermo Navarro and Emmanuel Lubezki. Mexican cinema today spans various genres, including comedy (e.g., films by Eugenio Derbez), horror (e.g., "Tigers Are Not Afraid" by Issa López), and drama.

National holidays

[edit]

Mexicans celebrate their Independence from Spain on September 16, and other holidays are celebrated with festivals known as "Fiestas". Many Mexican cities, towns, and villages hold a yearly festival to commemorate their local patron saints. During these festivities, the people pray and burn candles to honor their saints in churches decorated with flowers and colorful utensils. They also hold large parades, fireworks, dance competitions, and beauty pageant contests, all the while partying and buying refreshments in the marketplaces and public squares. In the smaller towns and villages, soccer, and boxing are also celebrated during the festivities.[23]

Other festivities include Día de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe ("Our Lady of Guadalupe Day"), Las Posadas ("The Shelters", celebrated on December 16 to December 24), Noche Buena ("Holy Night", celebrated on December 24), Navidad ("Christmas", celebrated on December 25) and Año Nuevo ("New Year's Day", celebrated on December 31 to January 1).

"Guadalupe Day" is regarded by many Mexicans as the most important religious holiday of their country. It honors the Virgin of Guadalupe, the patron saint of Mexico, and it is celebrated on December 12. In the last decade, all the celebrations happening from mid-December to the beginning of January have been linked together in what has been called the Guadalupe-Reyes Marathon.[24]

Epiphany on the evening of January 5 marks the Twelfth Night of Christmas and is when the figurines of the three wise men are added to the nativity scene. Traditionally in Mexico, as with many other Latin American countries, Santa Claus does not hold the significance that he does in the United States. Rather, it is the three wise men who are the bearers of gifts, who leave presents in or near the shoes of small children.[25] Mexican families also commemorate the date by eating Rosca de reyes.

The Day of the Dead incorporates pre-Columbian beliefs with Christian elements. The holiday focuses on gatherings of family and friends to pray for and remember friends and family members who have died. An idea behind this day suggests the living must attend to the dead so that the dead will protect the living.[26] The celebration occurs on November 2 in connection with the Catholic holidays of All Saints' Day (November 1) and All Souls' Day (November 2). Traditions connected with the holiday include building private altars honoring the deceased, using sugar skulls, marigolds, and the favorite foods and beverages of the departed, and visiting graves with these as gifts. The gifts presented turn the graveyard from a dull and sorrowful place to an intimate and hospitable environment to celebrate the dead.[26]

In modern Mexico, particularly in the larger cities and in the North, local traditions are now being observed and intertwined with the greater North American Santa Claus tradition, as well as with other holidays such as Halloween, due to Americanization via film and television, creating an economy of gifting tradition that spans from Christmas Day until January 6.

A piñata is made from papier-mache. It is created to look like popular people, animals, or fictional characters. Once made it is painted with bright colors and filled with candy or small toys. It is then hung from the ceiling. The children are blindfolded and take turns hitting the piñata until it breaks open and the candy and small toys fall out. The children then gather the candy and small toys.[27]

Cuisine

[edit]

Mexican cuisine is known for its blending of Indigenous and European cultures. The cuisine was inscribed in 2010 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.[30] Traditionally, the main Mexican ingredients consisted of maize, beans, both red and white meats, potatoes, tomatoes, seafood, chili peppers, squash, nuts, avocados and various herbs native to Mexico.

Popular dishes include tacos, enchiladas, mole sauce, atole, tamales, and pozole. Popular beverages include water flavored with a variety of fruit juices, and cinnamon-flavored hot chocolate prepared with milk or water and blended until it becomes frothed using a traditional wooden tool called a molinillo. Alcoholic beverages native to Mexico include mescal, pulque, and tequila. Mexican beer is also popular in Mexico and are exported. There are international award-winning Mexican wineries that produce and export wine.[31]

The most important and frequently used spices in Mexican cuisine are chili powder, cumin, oregano, cilantro, epazote, cinnamon, and cocoa. Chipotle, a smoked-dried jalapeño pepper, is also common in Mexican cuisine. Many Mexican dishes also contain onions and garlic, which are also some of Mexico's staple foods.[32]

Next to corn, rice is the most common grain in Mexican cuisine. According to food writer Karen Hursh Graber, the initial introduction of rice to Spain from North Africa in the 14th century led to the Spanish introduction of rice to Mexico at the port of Veracruz in the 1520s. This, Graber says, created one of the earliest instances of the world's greatest Fusion cuisines.[33][34]

In southeastern Mexico, especially in the Yucatán Peninsula, spicy vegetable and meat dishes are common. The cuisine of Southeastern Mexico has quite a bit of Caribbean influence, given its geographical location. Seafood is commonly prepared in the states that border the Pacific Ocean or the Gulf of Mexico, the latter having a famous reputation for its fish dishes, à la veracruzana.

Chocolate originated in Mexico and was prized by the Aztecs. It remains an important ingredient in Mexican cookery.[35]

Vanilla originated in Mexico. It was first cultivated by the Totonacs of Mexico's east coast. Vanilla is used in Mexico to flavor horchata and Mexican desserts such as churros.[36]

Mexican tea culture is known for its traditional herbal teas such as chamomile, linden, orange blossom, spearmint and lemongrass.[37]

Music and dance

[edit]

Mexican music is deeply rooted in its indigenous heritage, reflecting the rich cultural history of the region. The original inhabitants of Mexico used a variety of traditional instruments, including drums like the teponaztli, flutes, rattles, conches as trumpets, and their voices to create music and accompany dances. These sounds were integral to ceremonial events such as Netotiliztli. Although ancient music persists in certain areas, much of contemporary Mexican music emerged during and after the Spanish colonial period. This era saw the incorporation of European instruments into Mexican music, with some traditional instruments like the Mexican vihuela, used in Mariachi ensembles, evolving from their Old World counterparts into distinctly Mexican forms.[38]

Manuel M. Ponce, renowned for his composition "Estrellita," and Silvestre Revueltas, known for works such as "Sensemayá," are prominent figures in Mexican classical music. Other notable composers include Luis G. Jordá "Elodia," Ricardo Castro, Juventino Rosas, celebrated for "Sobre las olas," Mario Carrillo with his "Sonido 13," Julio Salazar, Pablo Moncayo, famous for "Huapango," and Carlos Chávez, a key figure in modern Mexican symphonic music.

The diversity of Mexican music genres highlights the complexity of Mexican culture. Traditional forms include Mariachi, Banda, Norteño (North style, redoba and accordion), Ranchera, Cumbia originating from Colombia but embraced in Mexico, and Corridos. These genres have gained international recognition, with notable popularity in countries such as Chile.[39][40] Iconic songs such as "Cielito Lindo," "La Adelita," "El Rey," "Jarabe Tapatío" (the Mexican Hat Dance), "La Llorona," "La Bamba," and "Las Mañanitas" are celebrated examples of traditional Mexican music. Other styles of traditional regional music in México: Huapango or Son Huasteco (Huasteca, northeastern regions, violin and two guitars known as quinta huapanguera and jarana), Tambora (Sinaloa, mainly brass instruments) Duranguense, Jarana (most of the Yucatán peninsula).

Folk songs known as corridos have been a significant element of Mexican music since the early 20th century, narrating stories related to the Mexican Revolution, romance, political themes, and other aspects of Mexican life. Additionally, Son Jarocho and the marimba contribute richly to the country's musical landscape, each representing distinct regional traditions and styles. Also in the early 20th century, Mariachi and Ranchera began to gain prominence, evolving through the contributions of artists such as Pedro Infante and Vicente Fernández.

Mariachi bands, characterized by their ensemble of singers, violins, guitarrón, guitarra de golpe, vihuela, guitars, and trumpets, perform at diverse venues such as streets, festivals, and restaurants.[41] The most renowned Mariachi group is Vargas de Tecalitlán, which was established in 1897 and has significantly influenced the genre. Folk dances are an integral part of Mexican culture, with the "Jarabe Tapatío," commonly known as the "Mexican hat dance," being particularly significant in dance tradition. This traditional dance features a sequence of hopping steps and heel and toe-tapping movements performed by dancers dressed in vibrant regional costumes.

Popular Mexican song composers include Agustín Lara, known for his romantic boleros; Consuelo Velázquez, celebrated for the iconic song "Bésame Mucho"; and José Alfredo Jiménez, recognized for his influential rancheras. Other notable composers are Armando Manzanero, famous for his boleros; Álvaro Carrillo, known for his poignant ballads; Joaquín Pardavé, who contributed to Mexican music and cinema; and Alfonso Ortiz Tirado, esteemed for his classical and operatic works. Juan Gabriel's songwriting was characterized by his deeply personal and emotive lyrics, blending traditional Mexican music with contemporary styles to create memorable and heartfelt songs.

In the latter half of the 20th century, Mexican rock and pop music began to emerge.[42] Bands like Caifanes and artists such as Luis Miguel became iconic figures in the Latin American music scene. The 1980s and 1990s saw the rise of new wave and rock en español, with influential groups lik Molotov and Maná leading the charge. Mexico boasts the largest media industry in Latin America, producing influential artists who achieve prominence across the Americas and Europe.[43]

Traditional Mexican music has influenced the evolution of the pop and Mexican rock genre. Some well-known Mexican pop singers are Thalía, Paulina Rubio, Jose Jose and Gloria Trevi. Mexican rock musicians such as Zoé, Café Tacvba, Las Ultrasonicas and Panteón Rococó have incorporated Mexican folk tunes into their music. Mexican contemporary musicians include Natalia Lafourcade, Julieta Venegas, Leonel García, and Carlos Rivera. Traditional Mexican music is still alive in the voices of artists such as Lila Downs, Aida Cuevas, Alejandro Fernández, Pepe Aguilar, Lupita Infante, and Lorenzo Negrete.

The annual Vive Latino festival in Mexico City is one of the largest and most influential music festivals in Latin America, drawing global attention and showcasing a diverse range of musical genres.

-

Northern Dance in Nuevo León

-

Jarabe Tapatío in the traditional China Poblana dress.

-

Danza de los Voladores, a ritual dance performed by the Totonacs.

-

Baile Flor de Piña, a traditional dance evoking the delicate of pineapple blossoms

Sport

[edit]

The traditional national sport of Mexico is Charreria, which consists of a series of equestrian events.[44] The national horse of Mexico, used in Charreria, is the Azteca. Bullfighting, a tradition brought from Spain, is also popular.[45] Mexico has the largest venue for bullfighting in the world - the Plaza México in Mexico City which seats 48,000 people. The country hosted the Summer Olympic Games in 1968 and the FIFA World Cup in 1970, 1986, and the upcoming 2026 and will be first country to host the FIFA World Cup three times.[46]

Football, as the most popular team sport in Mexico, is deeply ingrained in the nation's culture and identity. Each Mexican state typically supports its own local teams, fostering regional rivalries and a passionate fan base. The country's top clubs—Chivas de Guadalajara, Club América, Cruz Azul, and Pumas de la UNAM—are not only successful in domestic competitions but also have significant followings due to their storied histories and contributions to Mexican football. The sport has produced a number of internationally renowned players who have excelled both in domestic leagues and on the global stage. Hugo Sánchez is celebrated for his prolific scoring in La Liga, while Guillermo Ochoa is known for his impressive performances in European leagues and World Cups. Rafael Márquez, a versatile defender, has had a distinguished career in both European and Mexican football. In addition to club football, the Mexican national team, known as "El Tri", has a storied history in international competitions, including multiple appearances in the FIFA World Cup and successful campaigns in regional tournaments such as the CONCACAF Gold Cup.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Mexican colleges began integrating physical education into their curricula, initially focusing on individual sports such as track and field. Over time, especially from the mid-20th century onward, American football gained popularity among college students, reflecting the growing influence of American sports culture. Soccer remains the most popular college sport in Mexico, with competitive programs at universities such as the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) and the Universidad de Guadalajara (UDG). Basketball also has a significant presence, with strong teams from institutions like the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México (ITAM) and the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León (UANL). Although American football is less prevalent, it is expanding, particularly within organizations like ONEFA, involving universities like UNAM's Pumas CU and the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education (Monterrey ITESM) Borregos Salvajes Monterrey. Volleyball, track and field, swimming, and tennis are also prominent, with universities such as the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez (UACJ) and the Universidad de Guadalajara (UDG) maintaining competitive programs.

Mexico has a long tradition in combat sports. Boxing is the most popular and successful, which has turned the country into a world power with more than 110 world champions in various weight categories. In taekwondo, the second most practiced sport at the national level, it is one of the top exponents with 7 Olympic medals (two gold, two silver and three bronze). In mixed martial arts (MMA) there are also world champions of Mexican origin, being the only Hispanic American country to achieve this. Finally, sports such as judo and karate have also had talented representatives of Mexican origin, although to a lesser extent.

Automobile Dominance and Infrastructure

[edit]

In Mexico, personal transportation is predominantly centered around automobiles, with the country's infrastructure and car culture reflecting its unique economic, social, and geographical context. Mexico features an extensive road network of approximately 250,000 kilometers (155,000 miles), connecting major urban centers and supporting both trade and personal travel, though rural areas often face less-developed infrastructure. Car ownership has been rising, particularly in urban areas, with about 200 vehicles per 1,000 people, making cars a key mode of commuting for many Mexicans. Mexico's automotive sector is robust, housing major international manufacturers like General Motors, Volkswagen, and Nissan, and emerging interest in electric and hybrid vehicles is supported by government incentives. Car culture in Mexico often emphasizes practicality and affordability, with car shows and enthusiast clubs reflecting a growing passion for vehicles, especially among younger generations. However, traffic congestion in cities like Mexico City poses significant challenges, leading to ongoing efforts to improve public transportation and road conditions. Economic factors, including vehicle affordability and fuel costs, influence car ownership, while environmental concerns drive regulations and initiatives for cleaner technologies. The Mexican government continues to invest in infrastructure development and technological advancements, aiming to enhance connectivity, reduce congestion, and promote sustainable practices in personal transportation.

See also

[edit]- Alebrije, folk art sculptures

- China Poblana

- Conquian, card game

- El Chavo del Ocho, sitcom

- Flag of Mexico

- Festivals in Mexico

- Folktales of Mexico

- Ghosts in Mexican culture

- List of museums in Mexico

- Lotería, game

- Mexican ceramics

- Mexican handcrafts and folk art

- Mexican tea culture

- Narcoculture in Mexico

- National symbols of Mexico

- Papel picado

- Quinceañera, celebration of a girl's fifteenth birthday

- Rebozo

- Rodeo

- Serape, shawl

- Textiles of Mexico

- Traditional Mexican handcrafted toys

- Vaquero

References

[edit]- ^ "Cultural exchanges between Mexico and the Philippines | Geo-Mexico, the geography of Mexico". geo-mexico.com. 2010-09-04. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- ^ Hough, Walter (1900). "Oriental Influences in Mexico". American Anthropologist. 2 (1): 66–74. doi:10.1525/aa.1900.2.1.02a00060. hdl:2027/loc.ark:/13960/t2g745p90. ISSN 0002-7294. JSTOR 658862. S2CID 161852229.

- ^ Eye, The (2020-07-29). "Al Pastor and the Lebanese Influence on Mexican food". Beach, Village & Urban Living in Oaxaca. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- ^ "History of Korean Immigration to America, from 1903 to Present | Boston Korean Diaspora Project". sites.bu.edu. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- ^ Cocking, Lauren (2017-07-19). "The Untold History of Afro-Mexicans, Mexico's Forgotten Ethnic Group". Culture Trip. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- ^ "Mexico's Lasting European Influence". www.banderasnews.com. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- ^ Mexico - Daily life and social customs - Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Mexico". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Mexico". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Reich, Peter L. (Fall 1997). "The Mexican Catholic Church and Constitutional Change since 1929". The Historian. 60 (1): 77–86. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1997.tb01388.x. JSTOR 24451552.

- ^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 12 September 2022.

- ^ "Religión" (PDF). Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda 2000. INEGI. 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2005. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ^ "Church attendance". Study of worldwide rates of religiosity. University of Michigan. 1997. Archived from the original on 2006-09-01. Retrieved 2007-01-03.

- ^ "The Largest Catholic Communities". Adherents.com. Archived from the original on August 18, 2000. Retrieved 2007-11-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Mexican Folk Art - Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology

- ^ "Mexican muralists: the big three - Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros. : Mexico Culture & Arts". www.mexconnect.com. 2 June 2020.

- ^ "Western Literature". britannica.com.

- ^ "Learn Spanish in Mexico - Spanish Courses in Mexico - Spanish Schools in Mexico". Spanish-Language.com. Archived from the original on 2010-09-17. Retrieved 2010-02-18.

- ^ a b "Mexico - General country information". MoveOnNet.eu. Archived from the original on 2009-04-02. Retrieved 2010-02-18.

- ^ "Amerindian Words in English". Zompist.com. Retrieved 2010-02-18.

- ^ "Betraying the Maya". Archeology Magazine. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ Mullen, Robert J. (5 July 2010). Architecture and Its Sculpture in Viceregal Mexico. University of Texas Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-292-78805-3.

- ^ Hershfield, Joanne; MacIel, David R. (November 1999). Mexico's Cinema: A Century of Film and Filmmakers. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-585-24110-4.

- ^ Blackwell, Amy Hackney (2009). Independence Days. Infobase. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-4381-2795-8.

- ^ Kalman, Bobbie (2008). Mexico: The Culture. Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-7787-9295-6.

- ^ Botto, Ricardo. "Dia de Reyes, the story of Los Tres Reyes Magos". Mexonline.com. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Franco, Gina; Poore, Christopher (1 November 2017). "Day of the Dead is not "Mexican Halloween"—it's a day where death is reclaimed". America Magazine. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ "The mysterious origins of the piñata". BBC.

- ^ Hewitson, Carolyn (2013). Festivals. Routledge. ISBN 9781135057060.

It is said to resemble the star of Bethlehem. The Mexicans call it the flower of the Holy Night, but usually it is called poinsettia after the man who introduced it to America, Dr Joel Poinsett.

- ^ "The Legends and Traditions of Holiday Plants". www.ipm.iastate.edu. Archived from the original on January 22, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ^ "Traditional Mexican cuisine - ancestral, ongoing community culture, the Michoacán paradigm". UNESCO. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ "Mexico Wine Routes & Regions - Vineyards & Wineries of Baja". chiff.com. Retrieved 2010-02-18.

- ^ "Which Herbs and Spices Are Commonly Used in Mexican Cooking?".

- ^ Me n Mine-English. p. S-84.

- ^ Vegan Mexico: Soul-Satisfying Regional Recipes from Tamales to Tostadas. 2016.

- ^ "History of Chocolate". 10 August 2022.

- ^ "The History of Vanilla". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021.

- ^ "A Nice Cup of Tea: Searching for Camellia Sinensis". 2 May 2024.

- ^ Brill, Mark (22 December 2017). Music of Latin America and the Caribbean. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-68230-5.

- ^ Montoya Arias, Luis Omar; Díaz Güemez, Marco Aurelio (2017-09-12). "Etnografía de la música mexicana en Chile: Estudio de caso". Revista Electrónica de Divulgación de la Investigación (in Spanish). 14: 1–20.

- ^ Domic Kuscevic, Lenka (2000). "Geografía y literatura. Una aproximación metodológica". Estudios de Humaninades y Ciencias Sociales (in Spanish). 6: 51–54.

- ^ mariachi | music - Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ As well as an art, music is a way of life

- ^ Media industry in Mexico - statistics & facts

- ^ ""Mexican Charrería", a national sport" (PDF). gob.mx.

- ^ Sports and recreation - Mexico - Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ Dubov, Kalman (22 June 2022). Journeys to the United Mexican States. Kalman Dubov. p. 188.[self-published source?]