Belton Regio

| |

| Feature type | Dark region |

|---|---|

| Location | Pluto |

| Coordinates | 0°N 90°E / 0°N 90°E |

| Length | 3,000 km |

| Width | 1,000 km |

| Eponym | Michael J. Belton |

Belton Regio (formerly Cthulhu Macula or Cthulhu Regio[1][2]) is a prominent surface feature of the dwarf planet Pluto.[3] It is an elongated dark region along Pluto's equator, 2,990 km (1,860 mi) long and one of the darkest features on its surface.[4]

After its discovery in 2015, the feature was provisionally named after the fictional deity Cthulhu from the works of H. P. Lovecraft and others, as it was most popular name in its category in an online poll conducted earlier that year. In 2023, an official name was adopted by the International Astronomical Union honoring astronomer Michael J. Belton.

Description

[edit]The macula lies west of the Sputnik Planitia region of Tombaugh Regio, also known as Pluto's "heart", and to the east of Meng-P'o, the easternmost of Pluto's "Brass Knuckles".[5]

The dark color of the region is speculated to be the result of a "tar" made of complex hydrocarbons called tholins covering the surface, which form from methane and nitrogen in the atmosphere interacting with ultraviolet light and cosmic rays.[6][7][8] Tholins have been observed on other planetary bodies, such as Iapetus, Umbriel, and in the atmosphere of Titan, although the irregular and disconnected nature of the dark spots on Pluto has not yet been explained.[6]

The presence of craters within Belton indicates that it is perhaps billions of years old, in contrast to the adjacent bright, craterless Sputnik Planitia, which may be as little as 100 million years old;[9] however, some areas of Belton Regio are smoother and much more modestly cratered, and may be intermediate in age.

The eastern 'head' region consists mostly of heavily cratered 'alpine' terrain. The middle part of Belton Regio is meanwhile a smooth plain, probably formed through large cryovolcanic eruptions, like Vulcan Planum on Charon. This part appears to be younger than the alpine terrain to the east, but there are nevertheless several large craters located in this region. The western 'tail' region of Belton Regio was imaged in much lower resolution than the eastern part, but it can be inferred that this is a hilly landscape bordered by mountains to the west.[10][11][12] Higher-resolution images of the border between the two regions indicate that lighter material from Sputnik Planitia, composed of nitrogen, carbon monoxide, and methane ices, may be invading and overlaying the easternmost part of the dark Belton Regio.[13] As of 30 July 2015, the eastern "head" region had been imaged in much higher resolution than the western "tail" region.[14]

Belton Regio contains many craters and linear features that have also been given informal names. Oort Crater, K. Edgeworth Crater, and Elliot Crater are large craters along Belton's northern edge; Brinton Crater, Harrington Crater, and H. Smith Crater are near Belton's eastern edge, and Virgil Fossa and Beatrice Fossa are linear depressions in Belton's interior.[14]

-

The "head" region of the Belton feature, with Sputnik Planitia at right

-

The "tail" region of Belton, at the bottom of this image. The "head" extends beyond the right side of the visible portion of Pluto. Meng-P'o is visible at the extreme bottom left.

-

This image shows a region at the border between Belton's "head" (left) and the light, flat Sputnik Planitia (right), with Hillary Montes at center.

-

The white snow caps on a mountain range within Belton Regio (enhanced color, center) coincide with the spectral signature of methane ice (purple in false-color MVIC image, right).

Naming

[edit]

The feature was first identified in the initial image, first published on 8 July 2015, of Pluto returned after the New Horizons probe recovered from an anomaly that temporarily sent it into safe mode. NASA initially referred to it as "the Whale" in reference to its overall shape.[15][16]

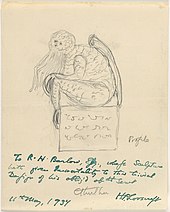

Surface features of Pluto were initially given provisional, informal names that are selected from a list generated from an online poll conducted earlier in 2015, along the theme of "creatures related to underworld mythologies."[5] "Cthulhu" was the most popular name in this category of the poll,[17] and by 14 July 2015, it was used by the New Horizons team to refer to the feature. It was named after the fictional deity from the works of H. P. Lovecraft and others,[5] which initially appeared in Lovecraft's 1928 short story "The Call of Cthulhu", as a malevolent entity hibernating within an underwater city in the South Pacific.[18] In many of Lovecraft's stories, particularly The Whisperer in Darkness, the transneptunian planet Yuggoth is implied to be the same as Pluto, which was discovered around the time Lovecraft was writing the stories.[19]

The name received positive reaction from the press and social media,[5][20] with a Chicago Tribune editorial supporting the name and its democratic origin.[21] It was reported that the name Cthulhu may be submitted to the IAU as an official name.[5][22] Cthulhu Macula was initially called a regio, but was renamed as the largest of the maculae that span Pluto's equator.[1][2]

On 22 September 2023, the name "Belton Regio" was approved by the IAU for the feature, after astronomer Michael J. Belton.[23]

See also

[edit]- Geography of Pluto

- Lovecraft (crater) – a crater on Mercury

References

[edit]- ^ a b Amanda M. Zangari; et al. (November 2015). "New Horizons disk-integrated approach photometry of Pluto and Charon". AAS/Division for Planetary Sciences Meeting Abstracts #47. 47. American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting #47, id.210.01: 210.01. Bibcode:2015DPS....4721001Z.

- ^ a b Stern, S. A.; Grundy, W.; McKinnon, W. B.; Weaver, H. A.; Young, L. A. (2018). "The Pluto System After New Horizons". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 56 (1): 357–392. arXiv:1712.05669. Bibcode:2018ARA&A..56..357S. doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-081817-051935. S2CID 119072504.

- ^ "Planetary Names". planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ Feltman, Rachel (8 July 2015). "New map of Pluto reveals a 'whale' and a 'donut'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e McKinnon, Mika (14 July 2015). "Places on Pluto are Being Named for Your Darkest Imaginings". Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ a b Petersen, C. C. (3 July 2015). "Why the Dark Spots on Pluto?". TheSpacewriter's Ramblings. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Moskowitz, Clara (29 April 2010). "Strange Spots on Pluto May be Tar and Frost". Space.com. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Betz, Eric. "Pluto's bright heart and Charon's dark spot revealed in HD". Astronomy Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "NASA's New Horizons Finds Second Mountain Range in Pluto's 'Heart'". NASA. 21 July 2015. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Keeter, Bill (2 June 2016). "Secrets Revealed from Pluto's 'Twilight Zone'". NASA. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ "Craters on Pluto and Charon – Surface Ages and Impactor Populations" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2017.

- ^ Moore, J. M.; McKinnon, W. B.; Spencer, J. R.; Howard, A. D.; Schenk, P. M.; Beyer, R. A.; Nimmo, F.; Singer, K. N.; Umurhan, O. M.; White, O. L.; Stern, S. A.; Ennico, K.; Olkin, C. B.; Weaver, H. A.; Young, L. A.; Binzel, R. P.; Buie, M. W.; Buratti, B. J.; Cheng, A. F.; Cruikshank, D. P.; Grundy, W. M.; Linscott, I. R.; Reitsema, H. J.; Reuter, D. C.; Showalter, M. R.; Bray, V. J.; Chavez, C. L.; Howett, C. J. A.; Lauer, T. R.; et al. (2016). "The geology of Pluto and Charon through the eyes of New Horizons". Science. 351 (6279): 1284–1293. arXiv:1604.05702. Bibcode:2016Sci...351.1284M. doi:10.1126/science.aad7055. PMID 26989245. S2CID 206644622.

- ^ "New Horizons Discovers Flowing Ices on Pluto". NASA. 24 July 2015. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ a b "Informal Names for Features on Pluto". New Horizons. Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. 29 July 2015. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ "NASA's New Horizons: A 'Heart' from Pluto as Flyby Begins". NASA. 8 July 2015. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ Megan Gannon (16 May 2017). "How Did Pluto Get Its 'Whale'?". Space.com. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ Flood, Alison (15 July 2015). "Will HP Lovecraft's deity give his name to a feature on Pluto?". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Lovecraft, H.P (1928). "The Call of Cthulhu". Wikisource. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ Lovecraft, Howard Phillips (1931). "The Whisperer in Darkness (chapter 8)". Wikisource. Archived from the original on 19 April 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

Astronomers, with a hideous appropriateness they little suspect, have named this thing "Pluto." I feel, beyond question, that it is nothing less than nighted Yuggoth—and I shiver when I try to figure out the real reason why its monstrous denizens wish it to be known in this way at this especial time.

- ^ "How 'Mordor' and 'Cthulhu' found their way onto Pluto and its moons". Mashable. 16 July 2015. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "Tolkien and Lovecraft got spots on Pluto. Keep it that way". Chicago Tribune. 17 July 2015. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Feltman, Rachel (14 July 2015). "New data reveals that Pluto's heart is broken". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ^ "Two Names Approved for Pluto: Belton Regio and Safronov Regio | USGS Astrogeology Science Center". astrogeology.usgs.gov. 22 September 2023. Archived from the original on 1 December 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

External links

[edit] Media related to Belton Regio at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Belton Regio at Wikimedia Commons