Critical point (thermodynamics)

- Subcritical ethane, liquid and gas phase coexist.

- Critical point (32.17 °C, 48.72 bar), displaying critical opalescence.

- Supercritical ethane, fluid.[1]

In thermodynamics, a critical point (or critical state) is the end point of a phase equilibrium curve. One example is the liquid–vapor critical point, the end point of the pressure–temperature curve that designates conditions under which a liquid and its vapor can coexist. At higher temperatures, the gas comes into a supercritical phase, and so cannot be liquefied by pressure alone. At the critical point, defined by a critical temperature Tc and a critical pressure pc, phase boundaries vanish. Other examples include the liquid–liquid critical points in mixtures, and the ferromagnet–paramagnet transition (Curie temperature) in the absence of an external magnetic field.[2]

Liquid–vapor critical point

[edit]Overview

[edit]

For simplicity and clarity, the generic notion of critical point is best introduced by discussing a specific example, the vapor–liquid critical point. This was the first critical point to be discovered, and it is still the best known and most studied one.

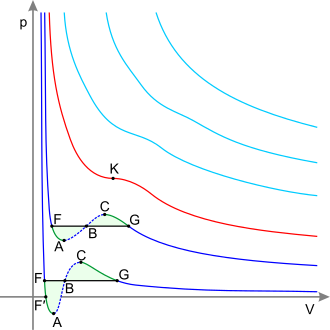

The figure shows the schematic P-T diagram of a pure substance (as opposed to mixtures, which have additional state variables and richer phase diagrams, discussed below). The commonly known phases solid, liquid and vapor are separated by phase boundaries, i.e. pressure–temperature combinations where two phases can coexist. At the triple point, all three phases can coexist. However, the liquid–vapor boundary terminates in an endpoint at some critical temperature Tc and critical pressure pc. This is the critical point.

The critical point of water occurs at 647.096 K (373.946 °C; 705.103 °F) and 22.064 megapascals (3,200.1 psi; 217.75 atm; 220.64 bar).[3]

In the vicinity of the critical point, the physical properties of the liquid and the vapor change dramatically, with both phases becoming even more similar. For instance, liquid water under normal conditions is nearly incompressible, has a low thermal expansion coefficient, has a high dielectric constant, and is an excellent solvent for electrolytes. Near the critical point, all these properties change into the exact opposite: water becomes compressible, expandable, a poor dielectric, a bad solvent for electrolytes, and mixes more readily with nonpolar gases and organic molecules.[4]

At the critical point, only one phase exists. The heat of vaporization is zero. There is a stationary inflection point in the constant-temperature line (critical isotherm) on a PV diagram. This means that at the critical point:[5][6][7]

Above the critical point there exists a state of matter that is continuously connected with (can be transformed without phase transition into) both the liquid and the gaseous state. It is called supercritical fluid. The common textbook knowledge that all distinction between liquid and vapor disappears beyond the critical point has been challenged by Fisher and Widom,[8] who identified a p–T line that separates states with different asymptotic statistical properties (Fisher–Widom line).

Sometimes[ambiguous] the critical point does not manifest in most thermodynamic or mechanical properties, but is "hidden" and reveals itself in the onset of inhomogeneities in elastic moduli, marked changes in the appearance and local properties of non-affine droplets, and a sudden enhancement in defect pair concentration.[9]

History

[edit]

The existence of a critical point was first discovered by Charles Cagniard de la Tour in 1822[10][11] and named by Dmitri Mendeleev in 1860[12][13] and Thomas Andrews in 1869.[14] Cagniard showed that CO2 could be liquefied at 31 °C at a pressure of 73 atm, but not at a slightly higher temperature, even under pressures as high as 3000 atm.

Theory

[edit]Solving the above condition for the van der Waals equation, one can compute the critical point as[5]

However, the van der Waals equation, based on a mean-field theory, does not hold near the critical point. In particular, it predicts wrong scaling laws.

To analyse properties of fluids near the critical point, reduced state variables are sometimes defined relative to the critical properties[15]

The principle of corresponding states indicates that substances at equal reduced pressures and temperatures have equal reduced volumes. This relationship is approximately true for many substances, but becomes increasingly inaccurate for large values of pr.

For some gases, there is an additional correction factor, called Newton's correction, added to the critical temperature and critical pressure calculated in this manner. These are empirically derived values and vary with the pressure range of interest.[16]

Table of liquid–vapor critical temperature and pressure for selected substances

[edit]| Substance[17][18] | Critical temperature | Critical pressure (absolute) |

|---|---|---|

| Argon | −122.4 °C (150.8 K) | 48.1 atm (4,870 kPa) |

| Ammonia (NH3)[19] | 132.4 °C (405.5 K) | 111.3 atm (11,280 kPa) |

| R-134a | 101.06 °C (374.21 K) | 40.06 atm (4,059 kPa) |

| R-410A | 72.8 °C (345.9 K) | 47.08 atm (4,770 kPa) |

| Bromine | 310.8 °C (584.0 K) | 102 atm (10,300 kPa) |

| Caesium | 1,664.85 °C (1,938.00 K) | 94 atm (9,500 kPa) |

| Chlorine | 143.8 °C (416.9 K) | 76.0 atm (7,700 kPa) |

| Ethane (C2H6) | 31.17 °C (304.32 K) | 48.077 atm (4,871.4 kPa) |

| Ethanol (C2H5OH) | 241 °C (514 K) | 62.18 atm (6,300 kPa) |

| Fluorine | −128.85 °C (144.30 K) | 51.5 atm (5,220 kPa) |

| Helium | −267.96 °C (5.19 K) | 2.24 atm (227 kPa) |

| Hydrogen | −239.95 °C (33.20 K) | 12.8 atm (1,300 kPa) |

| Krypton | −63.8 °C (209.3 K) | 54.3 atm (5,500 kPa) |

| Methane (CH4) | −82.3 °C (190.8 K) | 45.79 atm (4,640 kPa) |

| Neon | −228.75 °C (44.40 K) | 27.2 atm (2,760 kPa) |

| Nitrogen | −146.9 °C (126.2 K) | 33.5 atm (3,390 kPa) |

| Oxygen (O2) | −118.6 °C (154.6 K) | 49.8 atm (5,050 kPa) |

| Carbon dioxide (CO2) | 31.04 °C (304.19 K) | 72.8 atm (7,380 kPa) |

| Nitrous oxide (N2O) | 36.4 °C (309.5 K) | 71.5 atm (7,240 kPa) |

| Sulfuric acid (H2SO4) | 654 °C (927 K) | 45.4 atm (4,600 kPa) |

| Xenon | 16.6 °C (289.8 K) | 57.6 atm (5,840 kPa) |

| Lithium | 2,950 °C (3,220 K) | 652 atm (66,100 kPa) |

| Mercury | 1,476.9 °C (1,750.1 K) | 1,720 atm (174,000 kPa) |

| Sulfur | 1,040.85 °C (1,314.00 K) | 207 atm (21,000 kPa) |

| Iron | 8,227 °C (8,500 K) | |

| Gold | 6,977 °C (7,250 K) | 5,000 atm (510,000 kPa) |

| Aluminium | 7,577 °C (7,850 K) | |

| Water (H2O)[3][20] | 373.946 °C (647.096 K) | 217.7 atm (22,060 kPa) |

Mixtures: liquid–liquid critical point

[edit]

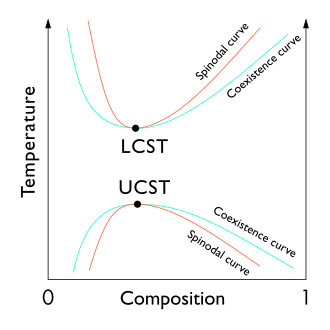

The liquid–liquid critical point of a solution, which occurs at the critical solution temperature, occurs at the limit of the two-phase region of the phase diagram. In other words, it is the point at which an infinitesimal change in some thermodynamic variable (such as temperature or pressure) leads to separation of the mixture into two distinct liquid phases, as shown in the polymer–solvent phase diagram to the right. Two types of liquid–liquid critical points are the upper critical solution temperature (UCST), which is the hottest point at which cooling induces phase separation, and the lower critical solution temperature (LCST), which is the coldest point at which heating induces phase separation.

Mathematical definition

[edit]From a theoretical standpoint, the liquid–liquid critical point represents the temperature–concentration extremum of the spinodal curve (as can be seen in the figure to the right). Thus, the liquid–liquid critical point in a two-component system must satisfy two conditions: the condition of the spinodal curve (the second derivative of the free energy with respect to concentration must equal zero), and the extremum condition (the third derivative of the free energy with respect to concentration must also equal zero or the derivative of the spinodal temperature with respect to concentration must equal zero).

See also

[edit]- Conformal field theory

- Critical exponent

- Critical phenomena (more advanced article)

- Critical points of the elements (data page)

- Curie point

- Joback method, Klincewicz method, Lydersen method (estimation of critical temperature, pressure, and volume from molecular structure)

- Liquid–liquid critical point

- Lower critical solution temperature

- Néel point

- Percolation thresholds

- Phase transition

- Rushbrooke inequality

- Scale invariance

- Self-organized criticality

- Supercritical fluid, Supercritical drying, Supercritical water oxidation, Supercritical fluid extraction

- Tricritical point

- Triple point

- Upper critical solution temperature

- Widom scaling

References

[edit]- ^ Horstmann, Sven (2000). Theoretische und experimentelle Untersuchungen zum Hochdruckphasengleichgewichtsverhalten fluider Stoffgemische für die Erweiterung der PSRK-Gruppenbeitragszustandsgleichung [Theoretical and experimental investigations of the high-pressure phase equilibrium behavior of fluid mixtures for the expansion of the PSRK group contribution equation of state] (Ph.D.) (in German). Oldenburg, Germany: Carl-von-Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg. ISBN 3-8265-7829-5. OCLC 76176158.

- ^ Stanley, H. Eugene (1987). Introduction to phase transitions and critical phenomena. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505316-8. OCLC 15696711.

- ^ a b Wagner, W.; Pruß, A. (June 2002). "The IAPWS Formulation 1995 for the Thermodynamic Properties of Ordinary Water Substance for General and Scientific Use". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 31 (2): 398. doi:10.1063/1.1461829.

- ^ Anisimov, Sengers, Levelt Sengers (2004): Near-critical behavior of aqueous systems. Chapter 2 in Aqueous System at Elevated Temperatures and Pressures Palmer et al., eds. Elsevier.

- ^ a b P. Atkins and J. de Paula, Physical Chemistry, 8th ed. (W. H. Freeman 2006), p. 21.

- ^ K. J. Laidler and J. H. Meiser, Physical Chemistry (Benjamin/Cummings 1982), p. 27.

- ^ P. A. Rock, Chemical Thermodynamics (MacMillan 1969), p. 123.

- ^ Fisher, Michael E.; Widom, B. (1969). "Decay of Correlations in Linear Systems". Journal of Chemical Physics. 50 (9): 3756. Bibcode:1969JChPh..50.3756F. doi:10.1063/1.1671624. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ Das, Tamoghna; Ganguly, Saswati; Sengupta, Surajit; Rao, Madan (3 June 2015). "Pre-Yield Non-Affine Fluctuations and A Hidden Critical Point in Strained Crystals". Scientific Reports. 5 (1): 10644. Bibcode:2015NatSR...510644D. doi:10.1038/srep10644. PMC 4454149. PMID 26039380.

- ^ Charles Cagniard de la Tour (1822). "Exposé de quelques résultats obtenu par l'action combinée de la chaleur et de la compression sur certains liquides, tels que l'eau, l'alcool, l'éther sulfurique et l'essence de pétrole rectifiée" [Presentation of some results obtained by the combined action of heat and compression on certain liquids, such as water, alcohol, sulfuric ether (i.e., diethyl ether), and distilled petroleum spirit]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique (in French). 21: 127–132.

- ^ Berche, B., Henkel, M., Kenna, R (2009) Critical phenomena: 150 years since Cagniard de la Tour. Journal of Physical Studies 13 (3), pp. 3001-1–3001-4.

- ^ Mendeleev called the critical point the "absolute temperature of boiling" (Russian: абсолютная температура кипения; German: absolute Siedetemperatur).

- Менделеев, Д. (1861). "О расширении жидкостей от нагревания выше температуры кипения" [On the expansion of liquids from heating above the temperature of boiling]. Горный Журнал [Mining Journal] (in Russian). 4: 141–152. The "absolute temperature of boiling" is defined on p. 151. Available at Wikimedia

- German translation: Mendelejeff, D. (1861). "Ueber die Ausdehnung der Flüssigkeiten beim Erwärmen über ihren Siedepunkt" [On the expansion of fluids during heating above their boiling point]. Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie (in German). 119: 1–11. doi:10.1002/jlac.18611190102. The "absolute temperature of boiling" is defined on p. 11: "Als absolute Siedetemperatur müssen wir den Punkt betrachten, bei welchem 1) die Cohäsion der Flüssigkeit = 0° ist und a2 = 0, bei welcher 2) die latente Verdamfungswärme auch = 0 ist und bei welcher sich 3) die Flüssigkeit in Dampf verwandelt, unabhängig von Druck und Volum." (As the "absolute temperature of boiling" we must regard the point at which (1) the cohesion of the liquid equals 0° and a2 = 0 [where a2 is the coefficient of capillarity, p. 6], at which (2) the latent heat of vaporization also equals zero, and at which (3) the liquid is transformed into vapor, independently of the pressure and the volume.)

- In 1870, Mendeleev asserted, against Thomas Andrews, his priority regarding the definition of the critical point: Mendelejeff, D. (1870). "Bemerkungen zu den Untersuchungen von Andrews über die Compressibilität der Kohlensäure" [Comments on Andrews' investigations into the compressibility of carbon dioxide]. Annalen der Physik. 2nd series (in German). 141 (12): 618–626. Bibcode:1870AnP...217..618M. doi:10.1002/andp.18702171218.

- ^ Landau, Lifshitz, Theoretical Physics, Vol. V: Statistical Physics, Ch. 83 [German edition 1984].

- ^ Andrews, Thomas (1869). "The Bakerian lecture: On the continuity of the gaseous and liquid states of matter". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 159. London: 575–590. doi:10.1098/rstl.1869.0021. S2CID 96898875. The term "critical point" appears on page 588.

- ^ Cengel, Yunus A.; Boles, Michael A. (2002). Thermodynamics: an engineering approach. Boston: McGraw-Hill. pp. 91–93. ISBN 978-0-07-121688-3.

- ^ Maslan, Frank D.; Littman, Theodore M. (1953). "Compressibility Chart for Hydrogen and Inert Gases". Ind. Eng. Chem. 45 (7): 1566–1568. doi:10.1021/ie50523a054.

- ^ Emsley, John (1991). The Elements (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-855818-7.

- ^ Cengel, Yunus A.; Boles, Michael A. (2002). Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach (Fourth ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 824. ISBN 978-0-07-238332-4.

- ^ "Ammonia – NH3 – Thermodynamic Properties". www.engineeringtoolbox.com. Retrieved 2017-04-07.

- ^ "Critical Temperature and Pressure". Purdue University. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

Further reading

[edit]- "Revised Release on the IAPWS Industrial Formulation 1997 for the Thermodynamic Properties of Water and Steam" (PDF). International Association for the Properties of Water and Steam. August 2007. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- "Critical points for some common solvents". ProSciTech. Archived from the original on 2008-01-31.

- "Critical Temperature and Pressure". Department of Chemistry. Purdue University. Retrieved 2006-12-03.