Crash (2004 film)

| Crash | |

|---|---|

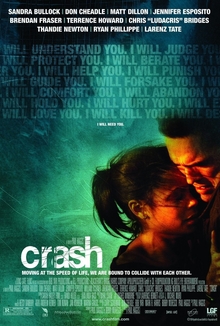

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Paul Haggis |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Paul Haggis |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | J. Michael Muro |

| Edited by | Hughes Winborne |

| Music by | Mark Isham |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 112 minutes[2] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6.5 million[1] |

| Box office | $98.4 million[1] |

Crash is a 2004 American crime drama film produced, directed, and co-written by Paul Haggis and Robert Moresco. A self-described "passion piece" for Haggis, the film features racial and social tensions in Los Angeles and was inspired by a real-life incident in which Haggis's Porsche was carjacked in 1991 outside a video store on Wilshire Boulevard.[3] The film features an ensemble cast, including Sandra Bullock, Don Cheadle, Matt Dillon, Jennifer Esposito, William Fichtner, Brendan Fraser, Terrence Howard, Chris "Ludacris" Bridges, Thandiwe Newton, Michael Peña, Larenz Tate and Ryan Phillippe.

Crash premiered at the 2004 Toronto International Film Festival on September 10, 2004, before it was released in theaters on May 6, 2005, by Lions Gate Films. The film received generally positive reviews from critics, who praised the direction and performances (particularly Dillon's) but criticized the portrayal of race relations as simplistic and unsubtle. The film was a success at the box office, earning $98.4 million worldwide against its $6.5 million budget.

The film earned several accolades and nominations. Dillon received nominations for Best Supporting Actor from the Academy Awards, BAFTA, Golden Globe, and Screen Actors Guild. Additionally, the cast won the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture. The film received six Academy Award nominations and controversially won three for Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Film Editing at the 78th Academy Awards. It was also nominated for nine BAFTA Awards and won two, for Best Original Screenplay and Best Supporting Actress for Newton.

Plot

[edit]In Los Angeles, Detective Graham Waters and his partner Ria are involved in a minor collision with a car being driven by Kim Lee. Ria and Kim Lee exchange racially charged insults. Waters later arrives at a crime scene, where the body of an unnamed dead child has been discovered. The film then backtracks 48 hours to trace the preceding chain of events.

Anthony and Peter, two young Black men, carjack district attorney Rick Cabot and his wife Jean. As the men drive away in the SUV, Peter puts a figurine of St. Christopher, the patron saint of travelers, on the dashboard. They pass by Waters and Ria, who are investigating a homicide in a San Fernando Valley parking lot. The pair learn that a white undercover cop, Detective Conklin, shot a black undercover cop, Detective Lewis, with neither knowing the other was a policeman.

At home, Cabot rails that the carjacking incident could cost him re-election, because no matter whom he sides with, he will lose either the black vote or the law and order vote. Hispanic locksmith Daniel Ruiz overhears Jean, who suspects that Daniel is a gangster, demanding that the locks be changed again.

While searching for the Cabots' stolen vehicle, Sergeant John Ryan pulls over an SUV driven by a wealthy Black couple, TV director Cameron Thayer and his wife, Christine. Though Ryan knows the vehicle is not the one he is searching for, he accosts the couple on his claim he saw Christine performing fellatio on Cameron while he was driving. During the traffic stop, Ryan performs a body search on Christine and molests her in front of Cameron. Ryan's younger partner, Officer Tom Hansen, looks on in horror but does not intervene.

Hansen goes to his superior Lieutenant Dixon to report Ryan's conduct and requests a transfer. Dixon, a Black man, tells Hansen that a racism complaint would hurt his own career and allows the transfer on the condition that Ryan's conduct not be mentioned. Ryan is shown living with his ill father, who cannot get health insurance. On the phone, Ryan takes out his frustrations on the black HMO administrator he speaks with. When the insurance adjuster does not respond quickly enough, Ryan insults her competency by saying that more qualified white men did not get her job because of affirmative action.

In the carjacked SUV, Anthony and Peter hit a man of Asian descent while passing a parked van. They take the injured man and leave him in front of a hospital. Meanwhile, Waters, who is in a relationship with Ria, gets into an argument with her when he makes a casual remark about Mexico being her country of origin. Ria angrily reminds him that her father is actually from Puerto Rico and her mother is from El Salvador. Waters later visits his mother, who asks him to find his missing younger brother.

Ryan later comes across a car crash and an overturned vehicle. In his attempt to rescue the passenger, Ryan sees it is Christine, who recognizes the officer from their earlier incident and frantically resists his assistance. Ryan manages to pull her out of the car just before it is engulfed by a fireball. As Christine is being helped by paramedics, she stares at Ryan.

Waters is summoned to a meeting with DA worker Flanagan, who tells Waters that Internal Affairs wants Conklin imprisoned. Waters has evidence that Lewis was possibly involved in a drug deal, but Flanagan promises Waters a job as Cabot's chief investigator, as well as the clearing of his brother's criminal record, in exchange for his cooperation. At a press conference, Waters reluctantly confirms the homicide was racially motivated.

Anthony and Peter carjack another Navigator, which happens to belong to Cameron. Cameron fights back and Peter flees the scene before a police car approaches. Cameron and Anthony drive away and a police chase ensues, with Hansen as one of the pursuing officers. When police catch the SUV, Hansen recognizes Cameron, and out of remorse for the earlier traffic stop, he vouches for Cameron to be let off with a warning. Anthony, who was hiding during the exchange, is dropped off at a bus stop by Cameron.

Later that night as Hansen is off the clock, he picks up a hitchhiking Peter. During the drive, Peter reaches into his pocket and Hansen, thinking he is reaching for a gun, shoots him. Peter collapses dead, revealing he was only reaching for his Saint Christopher statuette. Hansen hides the body in some bushes and burns his car. Waters and Ria later arrive at the scene, and it is revealed that the dead body is Waters's brother Peter. Waters's mother disowns him over Peter's death.

Anthony comes across the white van from earlier with its keys still in the ignition. He steals the van and takes it to a chop shop, where it is discovered there are Cambodian immigrants chained in the back. The van had belonged to Kim Lee and her husband (the man Anthony and Peter accidentally hit), meaning they were involved in human trafficking. The chop shop owner offers Anthony $500 per immigrant, but Anthony refuses. After driving the Cambodians to Chinatown and freeing them, he passes by a fender-bender. One driver turns out to be the insurance adjuster Ryan had previously argued with, and the other is an Asian man. An exchange of racially charged insults erupts between the drivers.

Cast

[edit]- Don Cheadle as Detective Graham Waters, a black officer investigating recent murders based on racial tensions

- Sandra Bullock as Jean Cabot, Rick's wife

- Matt Dillon as Sergeant John Ryan, a bigoted police officer

- Jennifer Esposito as Ria, Graham's Hispanic partner

- Brendan Fraser as District Attorney Rick Cabot, Jean's husband

- Terrence Howard as Cameron Thayer, a television director and Christine's husband

- Ludacris as Anthony, a violent carjacker and Peter's partner

- Thandiwe Newton (credited as Thandie Newton) as Christine Thayer, Cameron's wife

- Michael Peña as Daniel Ruiz, a Hispanic locksmith

- Ryan Phillippe as Officer Tom Hansen, a rookie policeman and Ryan's partner

- Larenz Tate as Peter, a laid back carjacker, and Anthony's partner

- Shaun Toub as Farhad, a Persian shop owner

- Bahar Soomekh as Dorri, Farhad's daughter

- Ashlyn Sanchez as Lara Ruiz, Daniel's daughter

- Karina Arroyave as Elizabeth Ruiz, Daniel's wife

- Loretta Devine as Shaniqua Johnson, a HMO administrator

- Beverly Todd as Mrs. Waters

- William Fichtner as Jake Flanagan, Rick's campaign manager

- Keith David as Lieutenant Dixon, Tom's superior officer

- Jack McGee as Gun Store Owner

- Greg Joung Paik as Choi Chin Gui, a human trafficker

- Alexis Rhee as Kim Lee, Choi Chin Gui's wife

- Daniel Dae Kim as Park

- Nona Gaye as Karen

- Bruce Kirby as "Pop" Ryan

- Tony Danza as Fred

- Kathleen York as Officer Johnson

- Sylva Kelegian as Nurse Hodges

- Marina Sirtis as Shereen, Farhad's wife

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Writer and director Paul Haggis was inspired to make the film after being carjacked by two African-American men at a Blockbuster Video on Wilshire Boulevard while driving home from the premiere of The Silence of the Lambs in February 1991.[4][5] Afterwards he began thinking more about the impact of race, ethnicity, and class in American society.[6][7] He later stated that he wrote Crash not simply to criticize racists but to "bust liberals" for the idea that the United States had become a post-racial society.[8] Haggis cowrote the first draft of Crash with Robert Moresco in 2001 after being fired from Family Law.[9][4]

Casting

[edit]Haggis initially tried to sell the script to television producers before it gained the attention of producers Cathy Schulman and Bob Yari.[9] Yari offered Haggis $7.5 million to produce the script as a film, on the condition he could assemble an ensemble cast of major stars.[9] Don Cheadle was the first actor to be cast and also came on board as a producer, which helped attract other big names to the production.[10][4] Forest Whitaker was originally attached to play Terrence Howard's role but dropped out.[9] The casting of Brendan Fraser as the district attorney, which came last, was pivotal in getting the film green-lit.[9]

Heath Ledger and John Cusack were also attached to the roles of Tom Hanson and John Ryan, respectively, but dropped out after production delays.[9] At one point, Don Cheadle also considered leaving the production to perform in Hotel Rwanda.[7] According to Yari, the departure of Ledger from the cast reduced the film's international value and the budget was brought down by $1 million.[9]

Filming

[edit]Filming began in Los Angeles for a 32-day shoot in December 2003.[9] Haggis made up for the reduced budget by taking out three mortgages on his house, cutting back on exterior shots, and reusing locations.[9] Principal cast members also agreed to pay cuts and deferred their salaries.[11] Production was delayed for a week when Haggis suffered from cardiac arrest while filming a scene, although he defied medical advice to hire a new director.[7][9][4]

In a 2020 interview with Vulture, Thandiwe Newton stated that Haggis ensured she was wearing special protective underwear for the police sexual assault scene, because he wanted it to look "real" from the camera's perspective for Matt Dillon "to go there".[12]

Music

[edit]The original score was released by Superb Records through Lionsgate Films in 2005.[13][14] All songs were written and composed by Mark Isham, except where noted.[13] The iTunes release is the complete score released through Yari Music Group, and has the cues isolated and in film order (unlike the commercial score CD which is edited, incomplete, in a different order, and in suite form).[15] A second volume of tracks, titled Crash: Music from and Inspired by the Film, was released featuring songs that appear in the film.[16][17]

Release

[edit]Box office

[edit]After a rough cut was shown at 2004 Toronto International Film Festival, the film premiered at the Elgin Theatre in Toronto in September 2004. It was quickly purchased by Lions Gate Films for $3.5 million.[7][10] Crash had a wide release on May 6, 2005, and was a box office success in the late spring of 2005.[18]

The film grossed $53.4 million domestically, making back more than seven times its estimated $6.5 million-budget.[1] Despite its success in relation to its cost, Crash was the lowest-grossing film at the domestic box office to win Best Picture since The Last Emperor in 1987.[19]

Home media

[edit]Crash was released on DVD on September 6, 2005, in widescreen and fullscreen one-disc versions.[20] Bonus features included a music video by KansasCali (now known as the Rocturnals) for the song "If I..." from the soundtrack. The director's cut of the film was released in a two-disc special edition DVD on April 4, 2006, with more bonus content than the one-disc set. The director's cut is three minutes longer than the theatrical cut. The scene where Daniel is talking with his daughter under her bed is extended and a new scene is added with officer Hansen in the police station locker room.[21]

Crash was the first Best Picture winner to be released on Blu-ray Disc in the US, on June 27, 2006.[22]

Critical response and legacy

[edit]Initial

[edit]On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 74% based on 242 reviews, with an average score of 7.2/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "A raw and unsettling morality piece on modern angst and urban disconnect, Crash examines the dangers of bigotry and xenophobia in the lives of interconnected Angelenos."[23] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 66 out of 100, based on 36 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[24] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film a grade of "A−" on an A+ to F scale.[25]

Roger Ebert gave the film four out of four stars and described it as "a movie of intense fascination",[26] listing it as the best film of 2005.[27] Ebert concluded his review with the sentiment "not many films have the possibility of making their audiences better people. I don't expect Crash to work any miracles, but I believe anyone seeing it is likely to be moved to have a little more sympathy for people not like themselves."[26] Steve Davis of the Austin Chronicle called it the "most compelling American movie to come around in a long time" and said it succeeds in inviting audiences to make preconceived notions about the characters and then complicates those notions.[28] Ella Taylor of LA Weekly described it as "not just one of the best Hollywood movies about race, but along with Collateral, one of the finest portrayals of contemporary LA life period."[29]

The performances of Dillon, Cheadle, Bridges, Peña, and Howard were singled out.[30][31][32][33] Todd McCarthy of Variety wrote, "Specific scenes, especially those involving Dillon as the racially resentful cop who, like everyone else, has his reasons, bristle with tension as the character continuously pushes past conventional limits in abusing his authority and, redeemingly, in his display of uncommon valor."[34][28] Peter Bradshaw of the Guardian gave the film three out of five stars, writing, "Crash is a very watchable and well-constructed piece of work...but its daringly supercharged fantasies of racial paranoia and humanist redemption are not to be taken too seriously."[35] Joanne Kaufman of the Wall Street Journal opined, "Ultimately, Crash succeeds in spite of itself," noting that at a certain point, it "starts to feel obvious and schematic" but remains "a complex blend of compassion and sorrow".[36]

The film's plot elements, such as the means through which all the characters are connected, were derided by critics as contrived and unconvincing.[37][38][31][39] Ty Burr of the Boston Globe wrote that the film "is one of those multi-character, something-is-rotten-in-Los Angeles barnburners that grab you by the lapels and try desperately to shake you up. It's more artful than Grand Canyon, less artsy than Magnolia (LA gets dusted with snow instead of frogs), and much less of a mess than Falling Down."[32] Burr lamented how "its characters come straight from the assembly line of screenwriting archetypes, and too often they act in ways that archetypes, rather than human beings, do. You can feel its creator shuttling them here and there on the grid of greater LA, pausing portentously between each move."[32]

Another criticism centered on the storytelling as didactic and heavy-handed. Writing for Slate, David Edelstein commented Crash "might even have been a landmark film about race relations had its aura of blunt realism not been dispelled by a toxic cloud of dramaturgical pixie dust."[40] Others noted how the film had nothing new or insightful to say on racism, with Stephanie Zacharek of Salon writing that Crash "only confirms what we already know about racism: It's inside every one of us. That should be a starting point, not a startling revelation."[41][42] A.O. Scott of the New York Times described it as "a frustrating movie: full of heart and devoid of life; crudely manipulative when it tries hardest to be subtle; and profoundly complacent in spite of its intention to unsettle and disturb."[43]

Much criticism focused on how the film presents racism and its origins, with many noting its depiction of race relations as too simplistic and tidy. The redemption arcs of the white characters, particularly Sergeant Ryan, drew controversy for their execution.[44][45][34] Many opined that Ryan's redemption by way of his heroic rescue of Christine felt unearned.[45][44][46][40][33] Others pointed out the implausibility of Jean Cabot softening her racist attitudes because of an ankle sprain and the care of her Latina housemaid.[45] Clarisse Loughrey of the Independent wrote, "By presenting racism as nothing more than a personality issue in need of a fix, Crash absolves its white audience of any sense of collective responsibility."[44]

Retrospective

[edit]In the years since the film's release, criticism and debate about the film have grown alongside ongoing cultural dialogues about race and social movements in the United States.[47][48] In 2009, cultural critic Ta-Nehisi Coates criticized the film as shallow and "unthinking", naming Crash "the worst film of the decade".[49] The film has been described as using multicultural and sentimentalist imagery to cover over material and "historically sedimented inequalities" that continue to affect various racial groups in Los Angeles.[50]

In a retrospective review, Tim Grierson of The New Republic opined, "Haggis has characters hurl nasty epithets at one another, as if that's the most corrosive aspect of discrimination, failing to acknowledge that what's most destructive aren't the shouts but, rather, the whispers—the private jokes and long-held prejudices shared by likeminded people behind closed doors and far from public view."[51] The film was also criticized for depicting the Persian shopkeeper as a "deranged, paranoid individual who is only redeemed by what he believes is a mystical act of God".[52]

The film ranks at #460 in Empire's 2008 poll of the "500 Greatest Films of All Time".[53]

In 2010, the Independent Film & Television Alliance selected Crash as one of the 30 Most Significant Independent Films of the last 30 years.[54]

Top ten lists

[edit]Crash was listed on many critics' top ten lists.[55]

- 1st – Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times

- 1st – Steve Davis, Austin Chronicle

- 3rd – Kevin Thomas, Los Angeles Times

- 3rd – Richard Roeper, Ebert & Roeper[56]

- 3rd – Ella Taylor, L.A. Weekly

- 4th – Stephen Hunter, The Washington Post

- 6th – Christy Lemire, Associated Press[57]

- 7th – Claudia Puig, USA Today

- 8th – Richard Schickel, Time

- 8th – Lisa Schwarzbaum, Entertainment Weekly

- 9th – Peter Travers, Rolling Stone

Oscar controversy

[edit]At the 78th Academy Awards, Crash won the Oscar for Best Picture, triumphing over the heavily favored Brokeback Mountain in what is considered as one of the most notable Oscars upsets.[58][59] After announcing the award, presenter Jack Nicholson was caught on camera mouthing the word "whoa" out of apparent surprise at the result.[60] The film's use of moral quandary as a storytelling medium was widely reported as ironic since many saw it as the "safe" alternative to Brokeback Mountain, which is about a gay relationship (the other nominees, Good Night and Good Luck, Capote, and Munich also tackle heavy subjects of McCarthyism, homosexuality, and terrorism).[61] Critic Kenneth Turan suggested that Crash benefited from homophobia among Academy members,[62][63] some of whom openly voiced their discomfort with Brokeback Mountain due to its subject matter.[64][65][66] After the Oscars telecast, critic Roger Ebert insisted in his column that the better film won the award.[67][68]

Film Comment magazine placed Crash first on its list of "Worst Winners of Best Picture Oscars", followed by Slumdog Millionaire at #2 and Chicago at #3.[69] Similarly, a 2014 survey of film critics by The Atlantic identified the film's victory as among the most glaring mistakes made by the Academy Awards.[70] In 2017, David Ehrlich and Eric Kohn of IndieWire ranked Crash as the worst on its list of "Best Picture Winners of the 21st Century, Ranked from Worst to Best".[71]

In 2015, The Hollywood Reporter polled hundreds of Academy members, asking them to re-vote on past controversial decisions. For the 2005 Best Picture winner, Brokeback Mountain beat Crash and the other nominees.[72][73]

In a 2015 interview, Haggis commented, "Was [Crash] the best film of the year? I don't think so. There were great films that year. Good Night, and Good Luck – amazing film. Capote – terrific film. Ang Lee's Brokeback Mountain, great film. And Spielberg's Munich. I mean please, what a year. Crash, for some reason, affected people, it touched people. And you can't judge these films like that. I'm very glad to have those Oscars. They're lovely things. But you shouldn't ask me what the best film of the year was because I wouldn't be voting for Crash, only because I saw the artistry that was in the other films. Now however, for some reason that's the film that touched people the most that year. So I guess that's what they voted for, something that really touched them. And I'm very proud of the fact that Crash does touch you. People still come up to me more than any of my films and say: 'That film just changed my life.' I've heard that dozens and dozens and dozens of times. So it did its job there. I mean, I knew it was the social experiment that I wanted, so I think it's a really good social experiment. Is it a great film? I don't know."[74][75]

In a 2020 retrospective about the film and its Oscars win, K. Austin Collins of Vanity Fair wrote the film "is a throwback to a familiar strain of Oscar-friendly, liberal message movie—in which the 'message,' often, is that people are complicated, goodness is relative, and evil is not a terminal condition. It dramatizes racism the same way that classical Hollywood storytelling has long dramatized things: through a sense of character and intention and a guise of psychological realism, through arcs and archetypes, through a slow climb toward third-act revelations about who people really are as evinced by the things they've achieved, the changes they've undergone by film's end."[47]

In February 2024, David Fear of Rolling Stone ranked Crash as the worst Best Picture Oscar winner of the 21st century, criticizing what he described as the movie’s heavy-handed symbolism and its various caricatures. Fear concluded his commentary by stating, “We have a feeling that were we to revisit this list in the year 2050, Crash would still occupy this same slot.”[76]

Accolades

[edit]Crash received several awards and nominations, and was named one of the top ten films of the year by both the American Film Institute[77] and the National Board of Review.[78] The film was nominated for six awards at the 78th Academy Awards and won three, for Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Film Editing.[79] It was also nominated for nine British Academy Film Awards and won two, for Best Original Screenplay and Best Supporting Actress for Newton.[80] Dillon received nominations for best supporting actor at the Academy Awards,[79] British Academy Film Awards,[80] Golden Globe Awards,[81] and Screen Actors Guild Awards[82] for his performance. Additionally, the cast won the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture,[83] and Harris and Moresco won the Writers Guild of America Award for Best Original Screenplay.[84]

Television series

[edit]A 13-episode series premiered on the Starz network on October 17, 2008. The series features Dennis Hopper as a record producer in Los Angeles, California, and how his life is connected to other characters in the city, including a police officer (Ross McCall) and his partner, actress-turned-police officer, Arlene Tur. The cast consists of a Brentwood mother (Clare Carey), her real-estate developer husband (D. B. Sweeney), a former gang member-turned-EMT (Brian Tee), a street-smart driver (Jocko Sims), an undocumented Guatemalan immigrant (Luis Chavez), and a detective (Nick Tarabay).[85]

See also

[edit]- Grand Canyon (1991 film)

- Magnolia (1999 film)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Crash (2005)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on August 23, 2010. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- ^ "Crash (15)". British Board of Film Classification. March 4, 2005. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ Haggis, Paul, et al. Lions Gate Films DVD Video Release, Crash (Audio commentary). September 6, 2005.

- ^ a b c d Leibowitz, Ed (February 1, 2008). "The Fabulist: Paul Haggis Reflects on His Career". Los Angeles Magazine. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Stein, Ruthe (May 2, 2005). "AT THE FILM FESTIVAL / 'Crash' came to Paul Haggis in a dream -- and a carjacking". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Peters, Jenny (February 2, 2006). "Paul Haggis and Robert Moresco, 'Crash'". Variety. Archived from the original on March 30, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

When Haggis and his then-wife were accosted at gunpoint 10 years ago, the experience never left him.

- ^ a b c d Wright, Lawrence (2013). Going clear : Scientology, Hollywood, and the prison of belief. New York. ISBN 978-0-307-70066-7. OCLC 818318033.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Buxton, Ryan (June 19, 2014). "Paul Haggis Wrote 'Crash' To 'Bust Liberals'". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hunt, Stacey Wilson (December 4, 2016). "How Crash Crashed the Oscars". Vulture. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Rich, Joshua (May 16, 2005). "The story behind Paul Haggis' Crash". EW.com. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Waxman, Sharon (July 25, 2006). "'Crash' Principals Still Await Payments for Their Work". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Jung, E. Alex (July 7, 2020). "Thandie Newton Is Finally Ready to Speak Her Mind". Vulture. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ a b "Crash: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack". AllMusic. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "Crash: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack". Amazon. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "iTunes - Crash by Mark Isham". iTunes. May 6, 2005. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- ^ "Crash: Music from and Inspired by Crash". AllMusic. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "Crash: Music from & Inspired by Crash". Amazon. Archived from the original on January 12, 2007. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Davis, Marcia (May 11, 2005). "Hollywood's Provocative 'Crash' at the Intersection of Race and Reality". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Bukszpan, Daniel (February 24, 2011). "The 15 Lowest-Grossing Oscar Winners". CNBC. Archived from the original on March 30, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ Carpenter, John (September 6, 2005). "Crash". DVD Review & High Definition. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ Miller III, Randy (April 4, 2006). "Crash: 2-Disc Director's Cut Edition". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "Historical Blu-ray Release Dates". Bluray.HighDefDigest.com. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ "Crash (2004)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ "Crash Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ "Crash". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (May 5, 2005). "When racial worlds collide". Chicago Sun-Times. RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 18, 2005). "Ebert's Best 10 Movies of 2005". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Davis, Steve (May 6, 2005). "Crash". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Ella, Taylor (May 5, 2005). "Space Race". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on April 8, 2017. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Travers, Peter (May 5, 2005). "Crash". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 28, 2005. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Ansen, David (May 12, 2005). "Blockbusters? Who Needs 'Em?". Newsweek. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c Burr, Ty (May 6, 2005). "Well-acted 'Crash' is a course in stock characters". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Arnold, William (May 6, 2005). "'Crash' is driving in circles on the road of despair". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ a b McCarthy, Todd (September 21, 2004). "Crash". Variety. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (August 12, 2005). "Crash". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Kaufmann, Joanne (May 6, 2005). "Knight Lite: Crusaders Lose Again... to a Weak Script in Gory 'Kingdom of Heaven'". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Chocano, Carina (May 6, 2005). "'Crash'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 5, 2005. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Sarris, Andrew (May 16, 2005). "L.A.'s Race-and Traffic-Problems Face Off in Paul Haggis' Crash". Observer. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Bell, Josh (May 5, 2005). "Crash". Las Vegas Weekly. Archived from the original on November 30, 2005. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Edelstein, David (May 6, 2005). "Crash and Kingdom of Heaven". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Zacharek, Stephanie (May 7, 2005). ""Crash"". Salon.com. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (May 6, 2005). "Drama crashes through barriers already down". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Scott, A.O. (May 6, 2005). "Bigotry as the Outer Side of Inner Angst". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c Loughrey, Clarisse (May 5, 2020). "Why the spectre of Crash still haunts Hollywood, 15 years on". The Independent. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c Love, Tirhakah (May 6, 2020). "'Crash' 15 Years Later: Remembering a Truly Terrible, Award-Winning Movie". level.medium.com. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Schneider, Steve (May 5, 2005). "Annoying At Any Speed". Orlando Weekly. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Collins, K. Austin (May 7, 2020). "Best-Picture Winner Crash Just Turned 15. Is Anybody Celebrating?". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on February 5, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Charity, Justin (April 15, 2021). "Admit It, 'Crash' Has Influenced a Generation of Stories About Race". The Ringer. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Coates, Ta-Nehisi (December 30, 2009). "Worst Movie of the Decade". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- ^ "Film Criticism Current Issue". FilmCriticism.Allegheny.edu. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ Grierson, Tim (February 24, 2016). "Is Crash Truly the Worst Best Picture?". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Gormley, Paul (May 7, 2007). "Crash and the City". DarkMatter101.org. Archived from the original on December 25, 2009. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Films of All Time". EmpireOnline.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ "IFTA Picks 30 Most Significant Indie Films". The Wrap. September 8, 2010. Archived from the original on February 6, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ "Metacritic: 2005 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. March 14, 2022. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ "Ebert and Roeper Top Ten Lists (2000-2005))". www.innermind.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ "Flick picks of 2005". January 2006. Archived from the original on February 25, 2019. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- ^ Horn, John; King, Susan (March 6, 2006). "'Crash' Named Best Picture in Upset Over 'Brokeback'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 28, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Zauzmer, Ben (April 23, 2021). "The Math Behind Oscars' Biggest Best Picture Upsets Ever". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ "Crash Wins Best Picture: 2006 Oscars". YouTube. March 31, 2011. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ^ Sullivan, Kevin P. (March 2, 2018). "Why 'Crash' beat 'Brokeback Mountain' for Best Picture". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (March 5, 2006). "Breaking no ground: Why 'Crash' won, why 'Brokeback' lost and how the Academy chose to play it safe". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 26, 2006. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

- ^ "Maybe Crash's upset at the Oscars shouldn't have been such a surprise?". Los Angeles Times. April 16, 2009. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

- ^ Karger, Dave (March 10, 2006). "Big Night". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on March 11, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ Donaldson, Kayleigh (February 22, 2019). "The Oscars' Most Shocking Moment Is Still Crash (Not La La Land)". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ O'Neil, Tom (November 17, 2006). "Will secret prejudice hurt 'Dreamgirls' at the Oscars?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 30, 2006. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 6, 2006). "The fury of the 'Crash'-lash | Festivals & Awards". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 8, 2006). "In defense of the year's 'worst movie'". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ "Trivial Top 20: Worst Winners of Best Picture Oscars®". Film Comment. March–April 2012. Archived from the original on March 11, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- ^ Roumell, Graham (March 2014). "What was the biggest Oscar mistake ever made?". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- ^ Ehrlich, David; Kohn, Eric (December 1, 2017). "The Best Picture Winners of the 21st Century, Ranked from Worst to Best". IndieWire. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "Recount! Oscar Voters Today Would Make 'Brokeback Mountain' Best Picture Over 'Crash'". The Hollywood Reporter. February 18, 2015. Archived from the original on January 22, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ^ "Crash Burned: Academy Members Reassess Past Oscar Decisions". The Guardian. February 19, 2015. Archived from the original on February 28, 2016. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Child, Ben (August 12, 2015). "Paul Haggis: Crash didn't deserve best picture Oscar". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ^ Sepinwall, Alan (August 11, 2015). "Even the director of Crash wouldn't have voted for it for Best Picture". Hitfix.com. Archived from the original on August 12, 2015.

- ^ "Best Picture Oscar Winners of the 21st Century, Ranked". Rolling Stone. February 21, 2024. Archived from the original on February 21, 2024. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "AFI Awards 2005: AFI Movies of the Year". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Mohr, Ian (December 12, 2005). "NBR in 'Good' mood". Variety. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ a b "The 78th Academy Awards (2006) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ a b "British Academy Film Awards 2006". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Live coverage of 2006 Golden Globes". Variety. January 16, 2006. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Nominations Announced for the 12th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards". Screen Actors Guild. Archived from the original on September 22, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "SAG Awards 2006: Full list of winners". BBC News. January 30, 2006. Archived from the original on February 25, 2016. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Brokeback, Crash honored by WGA". UPI. February 5, 2006. Archived from the original on May 17, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Crash: A Starz Original Series". Starz.com. Archived from the original on October 15, 2009. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

External links

[edit]- 2004 films

- BAFTA winners (films)

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- 2004 drama films

- 2004 independent films

- Fictional portrayals of the Los Angeles Police Department

- Films about racism in the United States

- Films about race and ethnicity

- Films about hijackings

- Films adapted into television shows

- Films directed by Paul Haggis

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films set in the San Fernando Valley

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films whose editor won the Best Film Editing Academy Award

- Films whose writer won the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award

- American independent films

- Films whose writer won the Best Original Screenplay BAFTA Award

- Films with screenplays by Paul Haggis

- Films scored by Mark Isham

- Hyperlink films

- Lionsgate films

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s American films

- Films about police brutality

- 2006 controversies in the United States

- Obscenity controversies in film

- Advertising and marketing controversies in film

- Race-related controversies in film

- Films about police misconduct

- English-language independent films