Craniometry

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Craniometry is measurement of the cranium (the main part of the skull), usually the human cranium. It is a subset of cephalometry, measurement of the head, which in humans is a subset of anthropometry, measurement of the human body. It is distinct from phrenology, the pseudoscience that tried to link personality and character to head shape, and physiognomy, which tried the same for facial features.

Today, physical and forensic anthropologists use craniometry to study the evolution of human populations, determining the origin of ancient remains such as the Kennewick Man, or helping law enforcement to identify the race of the deceased.[1][2][3] Forensic anthropologists can correctly identify the perceived social race of an individual with rates from 81-99% accuracy depending on the craniometric data, the number of variables used, the populations, and the type of analysis.[4][5][6]

There is a rift between forensic and biological anthropologists in the use of race in craniometry, with biological anthropologists attempting to disprove any theory of biological race, compared to how many forensic anthropologists make factual inquiries based on societally-created racial categories.[7] It was once intensively practised in physical anthropology in the 19th and the first part of the 20th century. Theories attempting to scientifically justify the segregation of society based on race became popular at this time, one of their prominent figures being Georges Vacher de Lapouge (1854–1936), who divided humanity into various, hierarchized, different "races", spanning from the "Aryan white race, dolichocephalic" (from the Ancient Greek kephalê, head, and dolikhos, long and thin), to the "brachycephalic" (short and broad-headed) race. On the other hand, craniometry was also used as evidence against the existence of a "Nordic race" and also by Franz Boas who used the cephalic index to show the influence of environmental factors. Charles Darwin used craniometry and the study of skeletons to demonstrate his theory of evolution first expressed in On the Origin of Species (1859).

Quite separately, certain artists from the 15th century onward made measurements of heads and skulls with a view to attaining greater accuracy in their representation of those parts of the human frame. Bernard Palissy and Albrecht Dürer were pioneers in such researches.[8]

The cephalic index

[edit]Swedish professor of anatomy Anders Retzius (1796–1860) first used the cephalic index in physical anthropology to classify ancient human remains found in Europe. He classified brains into three main categories, "dolichocephalic" (from the Ancient Greek kephalê, head, and dolikhos, long and thin), "brachycephalic" (short and broad) and "mesocephalic" (intermediate length and width).

A similar classification was the vertical cephalic index, the categories of which were "chamaecranic" (low-skulled), "orthocranic", (medium high-skulled), and "hypsicranic" (high-skulled).

These terms were then used by Georges Vacher de Lapouge (1854–1936), one of the controversial founders of theories in this area and a theoretician of eugenics, who in L'Aryen et son rôle social (1899 – "The Aryan and his social role") divided humanity into various, hierarchized, different "races", spanning from the "Aryan white race, dolichocephalic", to the "brachycephalic" "mediocre and inert" race, best represented by the population of "France, Spain, Italy, all of Asia, and most of the Slavic countries".[9]

Between these, Vacher de Lapouge identified the "Homo europaeus" (Teutonic, Protestant, etc.), the "Homo alpinus" (Auvergnat, Turkish, etc.), and finally the "Homo mediterraneus" (Napolitano, Andalus, etc.). "Homo africanus" (Congo, Florida) was even excluded from the discussion. Vacher de Lapouge became one of the leading inspirations of Nazi antisemitism and Nazi ideology.[10] His classification was mirrored in William Z. Ripley in The Races of Europe (1899).

Craniometry and anthropology

[edit]

In 1784, Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton, who wrote many comparative anatomy memoirs for the Académie française, published the Mémoire sur les différences de la situation du grand trou occipital dans l'homme et dans les animaux (which translates as Memoir on the Different Positions of the Occipital Foramen in Man and Animals).

Six years later, Pieter Camper (1722–1789), distinguished both as an artist and as an anatomist, published some lectures containing an account of his craniometrical methods. These laid the foundation of all subsequent work.[8]

Pieter Camper invented the "facial angle", a measure meant to determine intelligence among various species. According to this technique, a "facial angle" was formed by drawing two lines: one horizontally from the nostril to the ear; and the other perpendicularly from the advancing part of the upper jawbone to the most prominent part of the forehead.

Camper claimed that antique statues presented an angle of 90°, Europeans of 80°, Black people of 70° and the orangutan of 58°, thus displaying a hierarchic view of mankind, based on a decadent conception of history. This scientific research was continued by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772–1844) and Paul Broca (1824–1880), founder of the Anthropological Society in 1859 in France.

In 1856, workers found in a limestone quarry the skull of a Neanderthal man, thinking it to be the remains of a bear. They gave the material to amateur naturalist Johann Karl Fuhlrott, who turned the fossils over to anatomist Hermann Schaaffhausen. The discovery was jointly announced in 1857, giving rise to paleoanthropology.

Measurements were first made to compare the skulls of men with those of other animals. This wide comparison constituted the first subdivision of craniometric studies.[8] The artist-anatomist Camper developed a theory to measure the facial angle, for which he is chiefly known in later anthropological literature.

Camper's work followed 18th-century scientific theories. His measurements of facial angle were used to liken the skulls of non-Europeans to those of apes.

"Craniometry" also played a role in the foundation of the United States and the ideologies or racism that would become ingrained in the American psyche. As John Jeffries articulates in The Collision of Culture the Anglo-American hegemony present in America during the eighteenth and nineteenth century helped establish "The American School of Craniometry" which helped establish the American and Western concept of race. As Jeffries points out the rigid establishment of race in eighteenth-century American society came from a new school of sciences which sought to distance Anglo-Saxons from the African American population. The distancing of the African population in American society through craniometry helped greatly in the efforts to scientifically prove they were inferior. The ideologies set forth by this new "American School" of thought were then used to justify maintaining an enslaved population to sustain the increasing number of slave plantations in the American South during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[11]

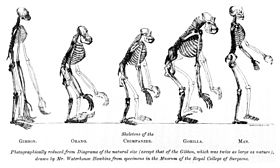

In the 19th century the names of notable contributors to the literature of craniometry quickly increased in number. While it is impossible to analyse each contribution, or even record a complete list of the names of the authors, notable researchers who used craniometric methods to compare humans to other animals included T. H. Huxley (1825–1895) of England and Paul Broca.[8]

By comparing skeletons of apes to man, Huxley backed up Charles Darwin's theory of evolution and developed the "Pithecometra principle", which stated that man and ape were descended from a common ancestor.

Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919) became famous for his now outdated "recapitulation theory", according to which each individual mirrored the evolution of the whole species during his life. Although outdated, his work contributed then to the examination of human life.

These researches on skulls and skeletons helped liberate 19th-century European science from its ethnocentric biases.[12] In particular, Eugène Dubois' (1858–1940) discovery in 1891 in Indonesia of the "Java Man", the first specimen of Homo erectus to be discovered, demonstrated mankind's deep ancestry outside Europe.

Cranial capacity, races and 19th–20th-century scientific ideas

[edit]Samuel George Morton (1799–1851), one of the inspirers of physical anthropology, collected hundreds of human skulls from all over the world and started trying to find a way to classify them according to some logical criterion. Influenced by the common theories of his time, he claimed that he could judge the intellectual capacity of a race by the cranial capacity (the measure of the volume of the interior of the skull).

After inspecting three mummies from ancient Egyptian catacombs, Morton concluded that Caucasians and other races were already distinct three thousand years ago. Since the Bible indicated that Noah's Ark had washed up on Mount Ararat, only a thousand years ago before this, Morton claimed that Noah's sons could not possibly account for every race on Earth. According to Morton's theory of polygenism, races have been separate since the start.[13]

Morton claimed that he could judge the intellectual capacity of a race by the skull size. A large skull meant a large brain and high intellectual capacity, and a small skull indicated a small brain and decreased intellectual capacity. Morton collected hundreds of human skulls from all over the world. By studying these skulls he claimed that each race had a separate origin. Morton had many skulls from ancient Egypt, and concluded that the ancient Egyptians were not African, but were White. His two major monographs were the Crania Americana (1839), An Inquiry into the Distinctive Characteristics of the Aboriginal Race of America and Crania Aegyptiaca (1844).

Based on craniometry data, Morton claimed in Crania Americana that the Caucasians had the biggest brains, averaging 87 cubic inches, Indians were in the middle with an average of 82 cubic inches and Negroes had the smallest brains with an average of 78 cubic inches.[13]

Stephen Jay Gould (1941–2002), an American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist and historian of science, studied these craniometric works in The Mismeasure of Man (1981) and claimed Samuel Morton had fudged data and "overpacked" the skulls with filler in order to justify his preconceived notions on racial differences. A subsequent study by the anthropologist John Michael found Morton's original data to be more accurate than Gould describes, concluding that "[c]ontrary to Gould's interpretation... Morton's research was conducted with integrity."[14]

In 2011, physical anthropologists at the University of Pennsylvania, which owns Morton's collection, published a study that concluded that almost every detail of Gould's analysis was wrong and that "Morton did not manipulate his data to support his preconceptions, contra Gould." They identified and remeasured half of the skulls used in Morton's reports, finding that in only 2% of cases did Morton's measurements differ significantly from their own and that these errors either were random or gave a larger than accurate volume to African skulls, the reverse of the bias that Gould imputed to Morton.[15]

Morton's followers, particularly Josiah C. Nott and George Gliddon in their monumental tribute to Morton's work, Types of Mankind (1854), carried Morton's ideas further and backed up his findings which supported the notion of polygenism.

Charles Darwin opposed Nott and Glidon in his 1871 The Descent of Man, arguing for a monogenism of the species. Darwin conceived the common origin of all humans (the single-origin hypothesis) as essential for evolutionary theory.

Furthermore, Josiah Nott was the translator of Arthur de Gobineau's An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races (1853–1855), which is one of the founding works of the group of studies that segregates society based on "race", in contrast to Boulainvilliers' (1658–1722) theory of races. Henri de Boulainvilliers opposed the Français (French people), alleged descendants of the Nordic Franks, and members of the aristocracy, to the Third Estate, considered to be indigenous Gallo-Roman people who were subordinated by the Franks by right of conquest.[clarification needed] Gobineau, meanwhile, made three main divisions between races, based not on colour but on climatic conditions and geographic location, and which privileged the "Aryan" race.

In 1873, Paul Broca (1824–1880) found the same pattern described by Samuel Morton's Crania Americana by weighing brains at autopsy. Other historical studies alleging a Black-White difference in brain size include Bean (1906), Mall, (1909), Pearl, (1934) and Vint (1934).

Furthermore, Georges Vacher de Lapouge's racial classification ("Teutonic", "Alpine" and "Mediterranean") was re-used by William Z. Ripley (1867–1941) in The Races of Europe (1899), who even made a map of Europe according to the alleged cephalic index of its inhabitants.

In Germany, Rudolf Virchow launched a study of craniometry, which gave surprising results according to contemporary theories on the "Aryan race", leading Virchow to denounce the "Nordic mysticism" in the 1885 Anthropology Congress in Karlsruhe.

Josef Kollmann, a collaborator of Virchow, stated in the same congress that the people of Europe, be them German, Italian, English or French, belonged to a "mixture of various races", furthermore declaring that the "results of craniology" led to "struggle against any theory concerning the superiority of this or that European race" on others.[16]

Virchow later rejected measure of skulls as legitimate means of taxonomy. Paul Kretschmer quoted an 1892 discussion with him concerning these criticisms, also citing Aurel von Törok's 1895 work, who basically proclaimed the failure of craniometry.[16]

Craniometry, phrenology and physiognomy

[edit]Craniometry was also used in phrenology, which purported to determine character, personality traits, and criminality on the basis of the shape of the head and thus of the skull. At the turn of the 19th century, Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1822) developed "cranioscopy" (Ancient Greek kranion: skull, scopos: vision), a method to determine the personality and development of mental and moral faculties on the basis of the external shape of the skull.

Cranioscopy was later renamed to phrenology (phrenos: mind, logos: study) by his student Johann Spurzheim (1776–1832), who wrote extensively on the "Drs. Gall and Spurzheim's physiognomical System". Physiognomy claimed a correlation between physical features (especially facial features) and character traits.

It was made famous by Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909), the founder of anthropological criminology, who claimed to be able to scientifically identify links between the nature of a crime and the personality or physical appearance of the offender. The originator of the concept of a "born criminal" and arguing in favor of biological determinism, Lombroso tried to recognize criminals by measurements of their bodies.

He concluded that skull and facial features were clues to genetic criminality, and that these features could be measured with craniometers and calipers with the results developed into quantitative research. A few of the 14 identified traits of a criminal included large jaws, forward projection of jaw, low sloping forehead; high cheekbones, flattened or upturned nose; handle-shaped ears; hawk-like noses or fleshy lips; hard shifty eyes; scanty beard or baldness; insensitivity to pain; long arms, and so on.

Criticisms and revival of past cranial theories in the 20th century

[edit]

After being a main influence of US white nationalists, William Ripley's The Races of Europe (1899) was eventually rewritten in 1939, just before World War II, by Harvard physical anthropologist Carleton S. Coon.[citation needed]

J. Philippe Rushton, psychologist and author of the controversial work Race, Evolution and Behavior (1995), reanalyzed Gould's retabulation in 1989, and argued that Samuel Morton, in his 1839 book Crania Americana, had shown a pattern of decreasing brain size proceeding from East Asians to Europeans to Africans.

In his 1995 book Race, Evolution, and Behavior, Rushton alleged an average endocranial volume of 1,364 cm3 for East Asians, 1,347 for white caucasians and 1,268 for black Africans. Other similar claims were previously made by Ho et al. (1980), who measured 1,261 brains at autopsy, and Beals et al. (1984), who measured approximately 20,000 skulls, finding the same East Asian → European → African pattern. However, in the same article Beals explicitly warns against using the findings as indicative of racial traits, "If one merely lists such means by geographical region or race, causes of similarity by genogroup and ecotype are hopelessly confounded".[17] Rushton's findings have also been criticized for questionable methodology, such as lumping in African-Americans with equatorial Africans, as people from hot climates generally have slightly smaller crania.[18] Rushton also compared equatorial Africans from the poorest and least educated areas of Africa against Asians from the wealthiest and most educated areas of Asia and areas with colder climates which generally induce larger cranium sizes in evolution.[18] According to Zack Cernovsky, from one of Rushton's own study it emerges that the average cranial capacity for North American blacks is similar to the average for Caucasians from comparable climatic zones.[18][19] Per Cernovsky, people from different climates tend to have minor differences in brain size, but these do not necessarily imply differences in intelligence; for instance, though women tend to have smaller brains than men they also have more neural complexity and loading in certain areas of the brain than men.[20][21]

Modern use

[edit]More direct measurements involve examinations of brains from corpses, or more recently, imaging techniques such as MRI, which can be used on living persons. Such measurements are used in research on neuroscience and intelligence.

Brain volume data and other craniometric data are used in mainstream science to compare modern-day animal species, and to analyze the evolution of the human species in archaeology.

Measurements of the skull based on specific anatomical reference points are used in both forensic facial reconstruction and portrait sculpture.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Anthropometry

- Cranial vault

- Craniofacial anthropometry

- Forensic anthropology

- Neuroscience and intelligence

- Samuel George Morton

- Theodor Kocher, inventor of the craniometer[22]

- Typology (anthropology)

References

[edit]- ^ Mann, Robert (2015). Berg, Gregory E.; Ta'Ala, Sabrina C. (eds.). The Sagittal Suture as an Indicator of Race and Sex. Biological Affinity in Forensic Identification of Human Skeletal Remains: Beyond Black and White. p. 106. doi:10.1201/b17832. ISBN 978-0-429-24504-6. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gill, George (1998). "Craniofacial Criteria in the Skeletal Attribution of Race". Journal of Anatomy. 194 (1) (2nd ed.). Forensic Osteology: Advances in the Identification of Human Remains: 293–295. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.1999.194101532.x. PMC 1467905.

- ^ Bonnichsen v. United States, 367 F.3d 864, 870-872 (9th Circuit 2004).

- ^ Mann, Robert (2015). The Sagittal Suture as an Indicator of Race and Sex. Biological Affinity in Forensic Identification of Human Skeletal Remains: Beyond Black and White. p. 111.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gill, George (1998). Craniofacial Criteria in the Skeletal Attribution of Race (2nd ed.). Forensic Osteology: Advances in the Identification of Human Remains. p. 305.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ousley, Stephen (2009). "Understanding Race and Human Variation: Why Forensic Anthropologists are Good at Identifying Race". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 139 (1): 71. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21006. PMID 19226647.

- ^ Ousley, Stephen (2009). "Understanding Race and Human Variation: Why Forensic Anthropologists are Good at Identifying Race". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 139 (1): 68–76. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21006. PMID 19226647.

- ^ a b c d Duckworth 1911, p. 372.

- ^ Hecht, Jennifer Michael (2003). The end of the soul: scientific modernity, atheism, and anthropology in France. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0231128469.

- ^ See Pierre-André Taguieff, La couleur et le sang – Doctrines racistes à la française ("Colour and Blood – doctrines à la française"), Paris, Mille et une nuits, 2002, 203 pages, and La Force du préjugé – Essai sur le racisme et ses doubles, Tel Gallimard, La Découverte, 1987, 644 pages

- ^ Wallace, Michele (1992). Black Popular Culture. Seattle: Bay Press. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-1-56584-459-9.

- ^ "Cultural Biases Reflected in the Hominid Fossil Record" (history), by Joshua Barbach and Craig Byron, 2005, ArchaeologyInfo.com webpage: ArchaeologyInfo-003 Archived 16 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b David Hurst Thomas, Skull Wars Kennewick Man, Archaeology, And The Battle For Native American Identity, 2001, pp. 38 – 41

- ^ Michael, J. S. (1988). "A New Look at Morton's Craniological Research". Current Anthropology. 29 (2): 349–354. doi:10.1086/203646. S2CID 144528631.

- ^ Lewis, Jason E.; DeGusta, D.; Meyer, M.R.; Monge, J.M.; Mann, A.E.; et al. (2011). "The Mismeasure of Science: Stephen Jay Gould versus Samuel George Morton on Skulls and Bias". PLOS Biol. 9 (6): e1001071. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001071. PMC 3110184. PMID 21666803.

- ^ a b Andrea Orsucci, "Ariani, indogermani, stirpi mediterranee: aspetti del dibattito sulle razze europee (1870–1914) Archived 18 December 2012 at archive.today, Cromohs, 1998 (in Italian)

- ^ Beals, Kenneth L.; et al. (1984). "Brain Size, Cranial Morphology, Climate, and Time Machines". Current Anthropology. 25 (3): 306. doi:10.1086/203138. JSTOR 2742800. S2CID 86147507.

- ^ a b c Cernovsky, Z. Z. (1997)A critical look at intelligence research, In Fox, D. & Prilleltensky, I. (Eds.) Critical Psychology, London: Sage, ps 121–133.

- ^ Rushton, J. P. (1990). "Race, Brain Size, and Intelligence: A Rejoinder to Cain and Vanderwolf". Personality and Individual Differences. 11 (8): 785–794. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(90)90186-u.

- ^ Insider – The Female Brain, By Ivory E. Welcome, MBA Candidate December 2009

- ^ Cosgrove, KP; Mazure, CM; Staley, JK (October 2007). "Evolving knowledge of sex differences in brain structure, function, and chemistry". Biol. Psychiatry. 62 (8): 847–55. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.001. PMC 2711771. PMID 17544382.

- ^ Schültke, Elisabeth (May 2009). "Theodor Kocher's craniometer". Neurosurgery. 64 (5). United States: 1001–4, discussion 1004–5. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000344003.72056.7F. PMID 19404160.

Sources

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Duckworth, Wynfrid Laurence Henry (1911). "Craniometry". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 372–374.