Toledo, Washington

Toledo, Washington | |

|---|---|

Shops on Cowlitz Street, Toledo, Washington (2019) | |

Location of Toledo, Washington | |

| Coordinates: 46°26′21″N 122°50′53″W / 46.43917°N 122.84806°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Lewis |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.40 sq mi (1.03 km2) |

| • Land | 0.39 sq mi (1.02 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 121 ft (37 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 631 |

| • Density | 1,956.85/sq mi (755.55/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 98591 |

| Area code | 360 |

| FIPS code | 53-71785 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1512731[3] |

| Website | ToledoWA.US |

Toledo is a city in Lewis County, Washington, United States. The population was 631 at the 2020 census.[4]

The community is home to an annual Cheese Days festival that celebrates the town's dairy history. Toledo residents gather at a yearly event known as the "Big Meeting" to discuss current concerns and to plan for the future of the city.

Etymology

[edit]The area underwent several names during its beginnings, including Plomondon's Landing, Warbassport, and Cowlitz Landing, changing roughly once a decade during the mid-1800s.[5] The moniker of Toledo was given in the 1870s and was named by Celeste Rochon after a pioneer side wheel paddle steamer operated by Captain Oren Kellogg of the Kellogg Transportation Company. The boat traveled the Cowlitz River.[6]

History

[edit]Simon Plomondon (or Plamondon), an employee of the Hudson Bay Company, settled in the area in 1820, taking up a donation land claim, marrying a Cowlitz Indian chief's (Chief Schanewah) daughter Thas-e-muth (Veronica) and becoming the first white man to settle in what would later be known as Southwest Washington. Their first child was born in what would become Toledo in 1821.[7] The early inhabitancy was not the first non-Indigenous settlement in the area, as the Pugets Sound Agricultural Company opened and maintained the Cowlitz Farm in 1839, near Toledo. In the mid-1850s during the Puget Sound War, volunteers constructed a blockhouse at Cowlitz Landing amid fears of potential Native American attacks; no combat at the fort took place.[8]

By the 1850s, a settlement known as Cowlitz Landing was formed after passengers of the river began disembarking during their journeys around the area. The landing was approximately 1.25 miles (2.01 km) southwest of present-day Toledo. The Cowlitz River changed course, eventually removing any remaining signs of the early community, and a new landing was established at the Tokul Creek junction. Another pioneer, Edward D. Warbass, began a port in the area after purchasing a claim in July 1850. The following year he established a post office known as Warbassport and served as a Lewis County treasurer and auditor for several years. In 1879, Captain Kellogg decided the area was conducive to build a town and began to purchase lands with that intent.[6]

Toledo was officially incorporated on October 10, 1892.[9]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 0.40 square miles (1.04 km2), all of it land.[10]

Climate

[edit]According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Toledo has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate, abbreviated "Csb" on climate maps.[11]

| Climate data for Toledo | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 62 (17) |

72 (22) |

80 (27) |

89 (32) |

93 (34) |

97 (36) |

102 (39) |

104 (40) |

100 (38) |

96 (36) |

71 (22) |

62 (17) |

104 (40) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 45.3 (7.4) |

50.8 (10.4) |

55.5 (13.1) |

60.4 (15.8) |

67 (19) |

72.4 (22.4) |

78 (26) |

78.8 (26.0) |

74.1 (23.4) |

62.9 (17.2) |

51.1 (10.6) |

44.9 (7.2) |

61.8 (16.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 33.2 (0.7) |

34.1 (1.2) |

36.3 (2.4) |

39 (4) |

43.7 (6.5) |

48.2 (9.0) |

50.4 (10.2) |

50 (10) |

46 (8) |

41.1 (5.1) |

37.7 (3.2) |

34.2 (1.2) |

41.2 (5.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 0 (−18) |

3 (−16) |

12 (−11) |

23 (−5) |

26 (−3) |

31 (−1) |

31 (−1) |

31 (−1) |

25 (−4) |

16 (−9) |

3 (−16) |

−2 (−19) |

−2 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.93 (176) |

5.04 (128) |

4.8 (120) |

3.16 (80) |

2.29 (58) |

2 (51) |

0.74 (19) |

1.43 (36) |

2.31 (59) |

3.73 (95) |

6.33 (161) |

6.91 (176) |

45.66 (1,160) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.9 (4.8) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.8 (2.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.8 (2.0) |

4.4 (11) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 inch) | 20 | 17 | 19 | 15 | 12 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 14 | 19 | 21 | 169 |

| Source: [12] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 276 | — | |

| 1900 | 285 | 3.3% | |

| 1910 | 375 | 31.6% | |

| 1920 | 324 | −13.6% | |

| 1930 | 530 | 63.6% | |

| 1940 | 523 | −1.3% | |

| 1950 | 602 | 15.1% | |

| 1960 | 499 | −17.1% | |

| 1970 | 654 | 31.1% | |

| 1980 | 637 | −2.6% | |

| 1990 | 586 | −8.0% | |

| 2000 | 653 | 11.4% | |

| 2010 | 725 | 11.0% | |

| 2020 | 631 | −13.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[13] 2020 Census[4] | |||

2010 census

[edit]As of the 2010 census,[14] there were 725 people, 274 households, and 199 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,812.5 inhabitants per square mile (699.8/km2). There were 304 housing units at an average density of 760.0 per square mile (293.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 91.0% White, 2.6% Native American, 0.8% Asian, 0.3% Pacific Islander, 2.3% from other races, and 2.9% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 7.0% of the population.

There were 274 households, of which 42.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.3% were married couples living together, 20.8% had a female householder with no husband present, 6.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 27.4% were non-families. 22.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.65 and the average family size was 3.04.

The median age in the city was 35.2 years. 28.4% of residents were under the age of 18; 11.4% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 22% were from 25 to 44; 24% were from 45 to 64; and 14.1% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 46.6% male and 53.4% female.

2000 census

[edit]As of the 2000 census, there were 653 people, 265 households, and 182 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,947.3 people per square mile (741.5/km2). There were 283 housing units at an average density of 843.9 per square mile (321.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 93.26% White, 0.61% African American, 2.30% Native American, 0.31% Asian, 1.53% from other races, and 1.99% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.90% of the population. 18.9% were of American, 13.7% German, 9.9% Irish, 8.0% English and 5.7% Dutch ancestry. 97.5% spoke English and 2.5% Spanish as their first language.

There were 265 households, out of which 32.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.3% were married couples living together, 12.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.3% were non-families. 28.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.46 and the average family size was 2.95.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 25.7% under the age of 18, 10.7% from 18 to 24, 24.3% from 25 to 44, 22.1% from 45 to 64, and 17.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 85.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 83.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $29,271, and the median income for a family was $31,833. Males had a median income of $28,750 versus $19,271 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,483. About 9.3% of families and 14.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 21.6% of those under age 18 and 3.8% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

[edit]

The residents of Toledo hold an annual "Big Toledo Community Meeting", or known locally as the "Big Meeting", to discuss ideas and plans for future events, to be informed of current projects within the town, and to hear about updates by local community and charitable organizations. The meeting began in 2011 as a way to invigorate the town after a large fire devastated a downtown historic building. Recent festivals and celebrations, such as a Santa Quad Parade and the New Year's Eve Giant Cheese Ball Drop, were developed based on proposals from the meeting. [15]

Festivals and events

[edit]Toledo celebrates the city's dairy farming history by hosting an annual Cheese Days festival, usually held in July. The festival began after the opening of a new cheese processing plant in 1919. A fire in 1945 decimated the factory but the yearly ceremonies continued.[5] In 2021, the festival observed the 100th occasion that the event had been held, and it has continued to honor the tradition of providing cheese sandwiches that were first offered at the inaugural Cheese Days celebration.[16][5] Since 1985, the festival has a grand marshal, titled as the Big Cheese, bestowed to an older and long-term resident of the community as an honor in recognition for their volunteer efforts.[17]

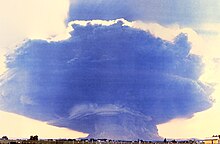

The Mt. St. Helens Bluegrass Festival is held annually in the city and features performances from bluegrass musicians from around the United States, including Appalachia and the Pacific Northwest. The festival is also known for its bluegrass quilting room. First debuting in 1984, the weekend event is usually held in August.[18][19]

Tourism

[edit]Gospodor Monument Park, a now closed but roadside-attraction park, is near the city and is viewable from I-5. The park consists of sculptures on tall plinths and smaller memorials.[20][21]

Parks and recreation

[edit]The Kemp Olson Memorial Park is the city's main park and is named after a long-time fire chief in the community.[5] South of Toledo and across the Cowlitz River sits the South County Park which provides access for boating and other activities around Wallace Pond.

Politics

[edit]Voting

[edit]| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020[22] | 59.47% 201 | 35.80% 121 | 4.44% 15 |

The 2020 election included votes for candidates of the Libertarian Party.

Government

[edit]

Toledo institutes a five-person city council that oversees economic and legislative matters, and an elected mayor that maintains daily oversight of the city and government staff.[23]

Education

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

Public education is provided by the Toledo School District, which serves both the City of Toledo and surrounding population. Campuses for students in elementary, middle, and high school are named after the city.[24]

The first school in Toledo was called the OK School. It was a one-room schoolhouse. Most of the kids that lived out of the town limits had to ride a boat across the river to and from school until the bridge was built. The school district consolidated 33 separate one-room schools in 1922. The school system mascot was the "Indians", a moniker that would exist for a century.[25] The current middle school was originally the high school until the new high school was built in 1974. While the middle school was being remodeled in 1995, the children were relocated for the year to St. Mary's Church and School.

St. Mary's Academy, begun in 1920, was a private-school for girls and began on the site of the Saint Francis Xavier Mission that first began in 1838. Despite large enrollment and funding figures in the 1960s, St. Mary's shuttered in June 1973 after severe loss of registrations due to negative economic conditions in the region.[26]

The Class of 1988 commissioned a totem pole from a chainsaw artist. This pole was presented to the high school by the class and continues to grace the front entrance. Since 1922, the school has used the "Indian" as the School's mascot. The Cowlitz Indian Tribe officially endorsed this mascot by Tribal Council action in February 2019. Artwork in the high school includes two Remington bronzes, an oil portrait of David Ike, last full-blooded Cowlitz Indian and several carvings by indigenous artists. Gary Ike, a long-time supporter of the school and its programs, is honored throughout the school and athletic venues in thanks for his many years of service to the school and community.

In November 2018, the community voted to build a new high school. Using funds from a special state grant and School Construction Assistance Program (SCAP) funding from the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, the upgraded high school was constructed on the site of the existing school.[27] Expansive construction of the new Toledo High School began in February 2020 and opened in autumn 2021. The school is built around the original gymnasium and features artwork honoring the Cowlitz Indian Tribe.[28] The $25 million construction project was completed in April 2022 followed by a ribbon cutting ceremony, unveilings of Native American artworks, and a performance by the Cowlitz Indian Tribe Drum Group.[29]

In 2021, the school district, required by a Washington state law banning Native American mascots and imagery enacted that year, changed its nickname to the Riverhawks.[25]

Sports

[edit]The Toledo boys' baseball team won the 2B state title in 2016.[30]

Infrastructure

[edit]Approximately 4.0 miles (6.4 km) north of Toledo is the South Lewis County Airport. Also known as Ed Carlson Memorial Field, the airfield is county owned but managed by a local commission.[31][32]

Notable people

[edit]- Ethan Siegel, theoretical astrophysicist and science author[33]

References

[edit]- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Toledo". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ a b "2020 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File". American FactFinder. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Vander Stoep, Isabel (July 3, 2023). "'Where's The Cheese?' in 102nd Year, Toledo Festival Still Cheesy". The Chronicle. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ a b "Toledo Early River Landing". The Daily Chronicle. October 10, 1966. p. G4. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ The Toledo Community Story, Geni, Lewis Talk, The Chronicle article by Andy Skinner - 9/27/2013

- ^ McDonald, Julie (September 26, 2022). "White Settlers Flee to Blockhouses During Indian Wars". The Chronicle. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ "City of Toledo History". City of Toledo, Washington. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ Climate Summary for Toledo, Washington

- ^ "TOLEDO, WASHINGTON (458500)". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Emily (May 13, 2022). "Toledo Residents Share Updates and New Ideas for Community at Annual 'Big Meeting'". The Chronicle. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ Vander Stoep, Isabel (July 5, 2021). "Cheese Days Returns to Toledo for the 100th Time". The Chronicle. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ McDonald Zander, Julie (2019). "A Brief History of Toledo Cheese Day" (PDF). toledolionsclub.org. Toledo Lions Club. pp. 31–35. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ Chronicle Staff (July 19, 2021). "Mount St. Helens Bluegrass Festival to Be Held at Park in Toledo". The Chronicle. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "Washington Bluegrass Music Festival Events". washingtonbluegrassassociation.org. Washington Bluegrass Association.

- ^ "Gospodor Monument Park". atlasobscura.com/. Atlas Obscura. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ Brewer, Christopher (January 9, 2015). "Gospodor Monument Will Live on In Toledo". The Chronicle. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ "Lewis County 2020 Election". Results.Vote.WA. Archived from the original on June 26, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Emily (December 23, 2022). "Toledo City Staff Resign Due to 'Difficult' Working Conditions". The Chronicle. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ "Toledo School District #237". toledoschools.us. Toledo School District. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ a b Rosane, Eric (August 20, 2021). "Toledo School District to Change Mascot to Riverhawks". The Chronicle. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ "St. Mary's Academy closing doors". The Daily Chronicle. March 13, 1973. p. 1. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Toledo voters overwhelmingly support school bond, The Daily News TDN.com, November 7, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ Rosane, Eric (August 6, 2021). "Construction of New Toledo High School Enters Final Stretch". The Chronicle. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ Chronicle Staff (April 24, 2022). "After a Long Road, Ribbon Cutting Marks Official Opening of New Toledo High School". The Chronicle. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ "The Brotherhood: Toledo Baseball's Biggest Asset". The Daily Chronicle. May 31, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2024.

- ^ Mittge, Brian (November 3, 2003). "Officials dedicate new airport runway in Toledo". The Chronicle. pp. A1, A12. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ^ Mittge, Brian (August 4, 2003). "South Lewis County airport leader has eyes for the sky". The Chronicle (Centralia, Washington). Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ^ Roland, Mitchell (October 17, 2023). "Toledo astrophysicist releases fourth book, first for children". The Chronicle. Retrieved November 9, 2023.