Cotton

| Cotton |

|---|

|

| History |

| Terminology |

| Types |

| Production |

| Fabric |

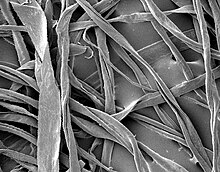

Cotton (from Arabic al-qutn) is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus Gossypium in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor percentages of waxes, fats, pectins, and water. Under natural conditions, the cotton bolls will increase the dispersal of the seeds.

The plant is a shrub native to tropical and subtropical regions around the world, including the Americas, Africa, Egypt and India. The greatest diversity of wild cotton species is found in Mexico, followed by Australia and Africa.[1] Cotton was independently domesticated in the Old and New Worlds.[2]

The fiber is most often spun into yarn or thread and used to make a soft, breathable, and durable textile. The use of cotton for fabric is known to date to prehistoric times; fragments of cotton fabric dated to the fifth millennium BC have been found in the Indus Valley civilization, as well as fabric remnants dated back to 4200 BC in Peru. Although cultivated since antiquity, it was the invention of the cotton gin that lowered the cost of production that led to its widespread use, and it is the most widely used natural fiber cloth in clothing today.

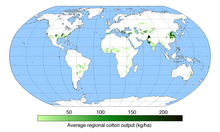

Current estimates for world production are about 25 million tonnes or 110 million bales annually, accounting for 2.5% of the world's arable land. India is the world's largest producer of cotton. The United States has been the largest exporter for many years.[3]

Types

There are four commercially grown species of cotton, all domesticated in antiquity:

- Gossypium hirsutum – upland cotton, native to Central America, Mexico, the Caribbean and southern Florida (90% of world production)[3]

- Gossypium barbadense – known as extra-long staple cotton, native to tropical South America (over 5% of world production)[4]

- Gossypium arboreum – tree cotton, native to India and Pakistan (less than 2%)

- Gossypium herbaceum – Levant cotton, native to southern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula (less than 2%)

Hybrid varieties are also cultivated.[5] The two New World cotton species account for the vast majority of modern cotton production, but the two Old World species were widely used before the 1900s. While cotton fibers occur naturally in colors of white, brown, pink and green, fears of contaminating the genetics of white cotton have led many cotton-growing locations to ban the growing of colored cotton varieties.

Etymology

The word "cotton" has Arabic origins, derived from the Arabic word قطن (qutn or qutun). This was the usual word for cotton in medieval Arabic.[6] Marco Polo in chapter 2 in his book, describes a province he calls Khotan in Turkestan, today's Xinjiang, where cotton was grown in abundance. The word entered the Romance languages in the mid-12th century,[7] and English a century later. Cotton fabric was known to the ancient Romans as an import, but cotton was rare in the Romance-speaking lands until imports from the Arabic-speaking lands in the later medieval era at transformatively lowered prices.[8][9]

History

Early history

South Asia

The earliest evidence of the use of cotton in the Old World, dated to 5500 BC and preserved in copper beads, has been found at the Neolithic site of Mehrgarh, at the foot of the Bolan Pass in ancient India, today in Balochistan Pakistan.[10][11][12] Fragments of cotton textiles have been found at Mohenjo-daro and other sites of the Bronze Age Indus Valley civilization, and cotton may have been an important export from it.[13]

Americas

Cotton bolls discovered in a cave near Tehuacán, Mexico, have been dated to as early as 5500 BC, but this date has been challenged.[14] More securely dated is the domestication of Gossypium hirsutum in Mexico between around 3400 and 2300 BC.[15] During this time, people between the Río Santiago and the Río Balsas grew, spun, wove, dyed, and sewed cotton. What they did not use themselves, they sent to their Aztec rulers as tribute, on the scale of ~116 million pounds annually.[16]

In Peru, cultivation of the indigenous cotton species Gossypium barbadense has been dated, from a find in Ancon, to c. 4200 BC,[17] and was the backbone of the development of coastal cultures such as the Norte Chico, Moche, and Nazca. Cotton was grown upriver, made into nets, and traded with fishing villages along the coast for large supplies of fish. The Spanish who came to Mexico and Peru in the early 16th century found the people growing cotton and wearing clothing made of it.

Arabia

The Greeks and the Arabs were not familiar with cotton until the Wars of Alexander the Great, as his contemporary Megasthenes told Seleucus I Nicator of "there being trees on which wool grows" in "Indica."[18] This may be a reference to "tree cotton", Gossypium arboreum, which is native to the Indian subcontinent.

According to the Columbia Encyclopedia:[19]

Cotton has been spun, woven, and dyed since prehistoric times. It clothed the people of ancient India, Egypt, and China. Hundreds of years before the Christian era, cotton textiles were woven in India with matchless skill, and their use spread to the Mediterranean countries.

Iran

In Iran (Persia), the history of cotton dates back to the Achaemenid era (5th century BC); however, there are few sources about the planting of cotton in pre-Islamic Iran. Cotton cultivation was common in Merv, Ray and Pars. In Persian poems, especially Ferdowsi's Shahname, there are references to cotton ("panbe" in Persian). Marco Polo (13th century) refers to the major products of Persia, including cotton. John Chardin, a French traveler of the 17th century who visited Safavid Persia, spoke approvingly of the vast cotton farms of Persia.[20]

Kingdom of Kush

Cotton (Gossypium herbaceum Linnaeus) may have been domesticated 5000 BC in eastern Sudan near the Middle Nile Basin region, where cotton cloth was being produced.[21] Around the 4th century BC, the cultivation of cotton and the knowledge of its spinning and weaving in Meroë reached a high level. The export of textiles was one of the sources of wealth for Meroë. Ancient Nubia had a "culture of cotton" of sorts, evidenced by physical evidence of cotton processing tools and the presence of cattle in certain areas. Some researchers propose that cotton was important to the Nubian economy for its use in contact with the neighboring Egyptians.[22] Aksumite King Ezana boasted in his inscription that he destroyed large cotton plantations in Meroë during his conquest of the region.[23]

In the Meroitic Period (beginning 3rd century BCE), many cotton textiles have been recovered, preserved due to favorable arid conditions.[22] Most of these fabric fragments come from Lower Nubia, and the cotton textiles account for 85% of the archaeological textiles from Classic/Late Meroitic sites.[24] Due to these arid conditions, cotton, a plant that usually thrives moderate rainfall and richer soils, requires extra irrigation and labor in Sudanese climate conditions. Therefore, a great deal of resources would have been required, likely restricting its cultivation to the elite.[24] In the first to third centuries CE, recovered cotton fragments all began to mirror the same style and production method, as seen from the direction of spun cotton and technique of weaving.[24] Cotton textiles also appear in places of high regard, such as on funerary stelae and statues.[24]

China

During the Han dynasty (207 BC - 220 AD), cotton was grown by Chinese peoples in the southern Chinese province of Yunnan.[25]

Middle Ages

Eastern world

Egyptians grew and spun cotton in the first seven centuries of the Christian era.[26]

Handheld roller cotton gins had been used in India since the 6th century, and was then introduced to other countries from there.[27] Between the 12th and 14th centuries, dual-roller gins appeared in India and China. The Indian version of the dual-roller gin was prevalent throughout the Mediterranean cotton trade by the 16th century. This mechanical device was, in some areas, driven by water power.[28]

The earliest clear illustrations of the spinning wheel come from the Islamic world in the eleventh century.[29] The earliest unambiguous reference to a spinning wheel in India is dated to 1350, suggesting that the spinning wheel was likely introduced from Iran to India during the Delhi Sultanate.[30]

Europe

During the late medieval period, cotton became known as an imported fiber in northern Europe, without any knowledge of how it was derived, other than that it was a plant. Because Herodotus had written in his Histories, Book III, 106, that in India trees grew in the wild producing wool, it was assumed that the plant was a tree, rather than a shrub. This aspect is retained in the name for cotton in several Germanic languages, such as German Baumwolle, which translates as "tree wool" (Baum means "tree"; Wolle means "wool"). Noting its similarities to wool, people in the region could only imagine that cotton must be produced by plant-borne sheep. John Mandeville, writing in 1350, stated as fact that "There grew there [India] a wonderful tree which bore tiny lambs on the endes of its branches. These branches were so pliable that they bent down to allow the lambs to feed when they are hungry." (See Vegetable Lamb of Tartary.)

Cotton manufacture was introduced to Europe during the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula and Sicily. The knowledge of cotton weaving was spread to northern Italy in the 12th century, when Sicily was conquered by the Normans, and consequently to the rest of Europe. The spinning wheel, introduced to Europe circa 1350, improved the speed of cotton spinning.[31] By the 15th century, Venice, Antwerp, and Haarlem were important ports for cotton trade, and the sale and transportation of cotton fabrics had become very profitable.[32]

Early modern period

Mughal India

Under the Mughal Empire, which ruled in the Indian subcontinent from the early 16th century to the early 18th century, Indian cotton production increased, in terms of both raw cotton and cotton textiles. The Mughals introduced agrarian reforms such as a new revenue system that was biased in favour of higher value cash crops such as cotton and indigo, providing state incentives to grow cash crops, in addition to rising market demand.[33]

The largest manufacturing industry in the Mughal Empire was cotton textile manufacturing, which included the production of piece goods, calicos, and muslins, available unbleached and in a variety of colours. The cotton textile industry was responsible for a large part of the empire's international trade.[34] India had a 25% share of the global textile trade in the early 18th century.[35] Indian cotton textiles were the most important manufactured goods in world trade in the 18th century, consumed across the world from the Americas to Japan.[36] The most important center of cotton production was the Bengal Subah province, particularly around its capital city of Dhaka.[37]

The worm gear roller cotton gin, which was invented in India during the early Delhi Sultanate era of the 13th–14th centuries, came into use in the Mughal Empire some time around the 16th century,[38] and is still used in India through to the present day.[27] Another innovation, the incorporation of the crank handle in the cotton gin, first appeared in India some time during the late Delhi Sultanate or the early Mughal Empire.[39] The production of cotton, which may have largely been spun in the villages and then taken to towns in the form of yarn to be woven into cloth textiles, was advanced by the diffusion of the spinning wheel across India shortly before the Mughal era, lowering the costs of yarn and helping to increase demand for cotton. The diffusion of the spinning wheel, and the incorporation of the worm gear and crank handle into the roller cotton gin, led to greatly expanded Indian cotton textile production during the Mughal era.[40]

It was reported that, with an Indian cotton gin, which is half machine and half tool, one man and one woman could clean 28 pounds of cotton per day. With a modified Forbes version, one man and a boy could produce 250 pounds per day. If oxen were used to power 16 of these machines, and a few people's labour was used to feed them, they could produce as much work as 750 people did formerly.[41]

Egypt

In the early 19th century, a Frenchman named M. Jumel proposed to the great ruler of Egypt, Mohamed Ali Pasha, that he could earn a substantial income by growing an extra-long staple Maho (Gossypium barbadense) cotton, in Lower Egypt, for the French market. Mohamed Ali Pasha accepted the proposition and granted himself the monopoly on the sale and export of cotton in Egypt; and later dictated cotton should be grown in preference to other crops.

Egypt under Muhammad Ali in the early 19th century had the fifth most productive cotton industry in the world, in terms of the number of spindles per capita.[42] The industry was initially driven by machinery that relied on traditional energy sources, such as animal power, water wheels, and windmills, which were also the principal energy sources in Western Europe up until around 1870.[43] It was under Muhammad Ali in the early 19th century that steam engines were introduced to the Egyptian cotton industry.[43]

By the time of the American Civil war annual exports had reached $16 million (120,000 bales), which rose to $56 million by 1864, primarily due to the loss of the Confederate supply on the world market. Exports continued to grow even after the reintroduction of US cotton, produced now by a paid workforce, and Egyptian exports reached 1.2 million bales a year by 1903.

Britain

East India Company

The English East India Company (EIC) introduced the British to cheap calico and chintz cloth on the restoration of the monarchy in the 1660s. Initially imported as a novelty side line, from its spice trading posts in Asia, the cheap colourful cloth proved popular and overtook the EIC's spice trade by value in the late 17th century. The EIC embraced the demand, particularly for calico, by expanding its factories in Asia and producing and importing cloth in bulk, creating competition for domestic woollen and linen textile producers. The impacted weavers, spinners, dyers, shepherds and farmers objected and the calico question became one of the major issues of National politics between the 1680s and the 1730s. Parliament began to see a decline in domestic textile sales, and an increase in imported textiles from places like China and India. Seeing the East India Company and their textile importation as a threat to domestic textile businesses, Parliament passed the 1700 Calico Act, blocking the importation of cotton cloth. As there was no punishment for continuing to sell cotton cloth, smuggling of the popular material became commonplace. In 1721, dissatisfied with the results of the first act, Parliament passed a stricter addition, this time prohibiting the sale of most cottons, imported and domestic (exempting only thread Fustian and raw cotton). The exemption of raw cotton from the prohibition initially saw 2 thousand bales of cotton imported annually, to become the basis of a new indigenous industry, initially producing Fustian for the domestic market, though more importantly triggering the development of a series of mechanised spinning and weaving technologies, to process the material. This mechanised production was concentrated in new cotton mills, which slowly expanded until by the beginning of the 1770s seven thousand bales of cotton were imported annually, and pressure was put on Parliament, by the new mill owners, to remove the prohibition on the production and sale of pure cotton cloth, as they could easily compete with anything the EIC could import.

The acts were repealed in 1774, triggering a wave of investment in mill-based cotton spinning and production, doubling the demand for raw cotton within a couple of years, and doubling it again every decade, into the 1840s.[44]

Indian cotton textiles, particularly those from Bengal, continued to maintain a competitive advantage up until the 19th century. In order to compete with India, Britain invested in labour-saving technical progress, while implementing protectionist policies such as bans and tariffs to restrict Indian imports.[44] At the same time, the East India Company's rule in India contributed to its deindustrialization, opening up a new market for British goods,[44] while the capital amassed from Bengal after its 1757 conquest was used to invest in British industries such as textile manufacturing and greatly increase British wealth.[45][46] British colonization also forced open the large Indian market to British goods, which could be sold in India without tariffs or duties, compared to local Indian producers who were heavily taxed, while raw cotton was imported from India without tariffs to British factories which manufactured textiles from Indian cotton, giving Britain a monopoly over India's large market and cotton resources.[47][44][48] India served as both a significant supplier of raw goods to British manufacturers and a large captive market for British manufactured goods.[49] Britain eventually surpassed India as the world's leading cotton textile manufacturer in the 19th century.[44]

India's cotton-processing sector changed during EIC expansion in India in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. From focusing on supplying the British market to supplying East Asia with raw cotton.[50] As the Artisan produced textiles were no longer competitive with those produced Industrially, and Europe preferring the cheaper slave produced, long staple American, and Egyptian cottons, for its own materials.[citation needed]

Industrial Revolution

The advent of the Industrial Revolution in Britain provided a great boost to cotton manufacture, as textiles emerged as Britain's leading export. In 1738, Lewis Paul and John Wyatt, of Birmingham, England, patented the roller spinning machine, as well as the flyer-and-bobbin system for drawing cotton to a more even thickness using two sets of rollers that traveled at different speeds. Later, the invention of the James Hargreaves' spinning jenny in 1764, Richard Arkwright's spinning frame in 1769 and Samuel Crompton's spinning mule in 1775 enabled British spinners to produce cotton yarn at much higher rates. From the late 18th century on, the British city of Manchester acquired the nickname "Cottonopolis" due to the cotton industry's omnipresence within the city, and Manchester's role as the heart of the global cotton trade.[51][52]

Production capacity in Britain and the United States was improved by the invention of the modern cotton gin by the American Eli Whitney in 1793. Before the development of cotton gins, the cotton fibers had to be pulled from the seeds tediously by hand. By the late 1700s, a number of crude ginning machines had been developed. However, to produce a bale of cotton required over 600 hours of human labor,[53] making large-scale production uneconomical in the United States, even with the use of humans as slave labor. The gin that Whitney manufactured (the Holmes design) reduced the hours down to just a dozen or so per bale. Although Whitney patented his own design for a cotton gin, he manufactured a prior design from Henry Odgen Holmes, for which Holmes filed a patent in 1796.[53] Improving technology and increasing control of world markets allowed British traders to develop a commercial chain in which raw cotton fibers were (at first) purchased from colonial plantations, processed into cotton cloth in the mills of Lancashire, and then exported on British ships to captive colonial markets in West Africa, India, and China (via Shanghai and Hong Kong).

By the 1840s, India was no longer capable of supplying the vast quantities of cotton fibers needed by mechanized British factories, while shipping bulky, low-price cotton from India to Britain was time-consuming and expensive. This, coupled with the emergence of American cotton as a superior type (due to the longer, stronger fibers of the two domesticated native American species, Gossypium hirsutum and Gossypium barbadense), encouraged British traders to purchase cotton from plantations in the United States and in the Caribbean. By the mid-19th century, "King Cotton" had become the backbone of the southern American economy. In the United States, cultivating and harvesting cotton became the leading occupation of slaves.

During the American Civil War, American cotton exports slumped due to a Union blockade on Southern ports, and because of a strategic decision by the Confederate government to cut exports, hoping to force Britain to recognize the Confederacy or enter the war. The Lancashire Cotton Famine prompted the main purchasers of cotton, Britain and France, to turn to Egyptian cotton. British and French traders invested heavily in cotton plantations. The Egyptian government of Viceroy Isma'il took out substantial loans from European bankers and stock exchanges. After the American Civil War ended in 1865, British and French traders abandoned Egyptian cotton and returned to cheap American exports,[citation needed] sending Egypt into a deficit spiral that led to the country declaring bankruptcy in 1876, a key factor behind Egypt's occupation by the British Empire in 1882.

During this time, cotton cultivation in the British Empire, especially Australia and India, greatly increased to replace the lost production of the American South. Through tariffs and other restrictions, the British government discouraged the production of cotton cloth in India; rather, the raw fiber was sent to England for processing. The Indian Mahatma Gandhi described the process:

- English people buy Indian cotton in the field, picked by Indian labor at seven cents a day, through an optional monopoly.

- This cotton is shipped on British ships, a three-week journey across the Indian Ocean, down the Red Sea, across the Mediterranean, through Gibraltar, across the Bay of Biscay and the Atlantic Ocean to London. One hundred per cent profit on this freight is regarded as small.

- The cotton is turned into cloth in Lancashire. You pay shilling wages instead of Indian pennies to your workers. The English worker not only has the advantage of better wages, but the steel companies of England get the profit of building the factories and machines. Wages; profits; all these are spent in England.

- The finished product is sent back to India at European shipping rates, once again on British ships. The captains, officers, sailors of these ships, whose wages must be paid, are English. The only Indians who profit are a few lascars who do the dirty work on the boats for a few cents a day.

- The cloth is finally sold back to the kings and landlords of India who got the money to buy this expensive cloth out of the poor peasants of India who worked at seven cents a day.[54]

United States

In the United States, growing Southern cotton generated significant wealth and capital for the antebellum South, as well as raw material for Northern textile industries. Before 1865 the cotton was largely produced through the labor of enslaved African Americans. It enriched both the Southern landowners and the new textile industries of the Northeastern United States and northwestern Europe. In 1860 the slogan "Cotton is king" characterized the attitude of Southern leaders toward this monocrop in that Europe would support an independent Confederate States of America in 1861 in order to protect the supply of cotton it needed for its very large textile industry.[55] Russell Griffin of California was a farmer who farmed one of the biggest cotton operations. He produced over sixty thousand bales.[56] Cotton remained a key crop in the Southern economy after slavery ended in 1865. Across the South, sharecropping evolved, in which landless farmers worked land owned by others in return for a share of the profits. Some farmers rented the land and bore the production costs themselves. Until mechanical cotton pickers were developed, cotton farmers needed additional labor to hand-pick cotton. Picking cotton was a source of income for families across the South. Rural and small town school systems had split vacations so children could work in the fields during "cotton-picking."[57]

During the middle 20th century, employment in cotton farming fell, as machines began to replace laborers and the South's rural labor force dwindled during the World Wars. Cotton remains a major export of the United States, with large farms in California, Arizona and the Deep South.[56] To acknowledge cotton's place in the history and heritage of Texas, the Texas Legislature designated cotton the official "State Fiber and Fabric of Texas" in 1997.

The Moon

China's Chang'e 4 spacecraft took cotton seeds to the Moon's far side. On 15 January 2019, China announced that a cotton seed sprouted, the first "truly otherworldly plant in history". Inside the Von Kármán Crater, the capsule and seeds sit inside the Chang'e 4 lander.[58]

Cultivation

Successful cultivation of cotton requires a long frost-free period, plenty of sunshine, and a moderate rainfall, usually from 50 to 100 cm (19.5 to 39.5 in).[citation needed] Soils usually need to be fairly heavy, although the level of nutrients does not need to be exceptional. In general, these conditions are met within the seasonally dry tropics and subtropics in the Northern and Southern hemispheres, but a large proportion of the cotton grown today is cultivated in areas with less rainfall that obtain the water from irrigation. Production of the crop for a given year usually starts soon after harvesting the preceding autumn. Cotton is naturally a perennial but is grown as an annual to help control pests.[59] Planting time in spring in the Northern hemisphere varies from the beginning of February to the beginning of June. The area of the United States known as the South Plains is the largest contiguous cotton-growing region in the world. While dryland (non-irrigated) cotton is successfully grown in this region, consistent yields are only produced with heavy reliance on irrigation water drawn from the Ogallala Aquifer. Since cotton is somewhat salt and drought tolerant, this makes it an attractive crop for arid and semiarid regions. As water resources get tighter around the world, economies that rely on it face difficulties and conflict, as well as potential environmental problems.[60][61][62][63][64] For example, improper cropping and irrigation practices have led to desertification in areas of Uzbekistan, where cotton is a major export. In the days of the Soviet Union, the Aral Sea was tapped for agricultural irrigation, largely of cotton, and now salination is widespread.[63][64]

Cotton can also be cultivated to have colors other than the yellowish off-white typical of modern commercial cotton fibers. Naturally colored cotton can come in red, green, and several shades of brown.[65]

Water footprint

The water footprint of cotton fibers is substantially larger than for most other plant fibers. Cotton is also known as a thirsty crop; on average, globally, cotton requires 8,000–10,000 liters of water for one kilogram of cotton, and in dry areas, it may require even more such as in some areas of India, it may need 22,500 liters.[66][67]

Genetic modification

Genetically modified (GM) cotton was developed to reduce the heavy reliance on pesticides. The bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) naturally produces a chemical harmful only to a small fraction of insects, most notably the larvae of moths and butterflies, beetles, and flies, and harmless to other forms of life.[68][69][70] The gene coding for Bt toxin has been inserted into cotton, causing cotton, called Bt cotton, to produce this natural insecticide in its tissues. In many regions, the main pests in commercial cotton are lepidopteran larvae, which are killed by the Bt protein in the transgenic cotton they eat. This eliminates the need to use large amounts of broad-spectrum insecticides to kill lepidopteran pests (some of which have developed pyrethroid resistance). This spares natural insect predators in the farm ecology and further contributes to noninsecticide pest management.

However, Bt cotton is ineffective against many cotton pests, such as plant bugs, stink bugs, and aphids; depending on circumstances it may still be desirable to use insecticides against these. A 2006 study done by Cornell researchers, the Center for Chinese Agricultural Policy and the Chinese Academy of Science on Bt cotton farming in China found that after seven years these secondary pests that were normally controlled by pesticide had increased, necessitating the use of pesticides at similar levels to non-Bt cotton and causing less profit for farmers because of the extra expense of GM seeds.[71] However, a 2009 study by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Stanford University and Rutgers University refuted this.[72] They concluded that the GM cotton effectively controlled bollworm. The secondary pests were mostly miridae (plant bugs) whose increase was related to local temperature and rainfall and only continued to increase in half the villages studied. Moreover, the increase in insecticide use for the control of these secondary insects was far smaller than the reduction in total insecticide use due to Bt cotton adoption. A 2012 Chinese study concluded that Bt cotton halved the use of pesticides and doubled the level of ladybirds, lacewings and spiders.[73][74] The International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA) said that, worldwide, GM cotton was planted on an area of 25 million hectares in 2011.[75] This was 69% of the worldwide total area planted in cotton.

GM cotton acreage in India grew at a rapid rate, increasing from 50,000 hectares in 2002 to 10.6 million hectares in 2011. The total cotton area in India was 12.1 million hectares in 2011, so GM cotton was grown on 88% of the cotton area. This made India the country with the largest area of GM cotton in the world.[75] A long-term study on the economic impacts of Bt cotton in India, published in the Journal PNAS in 2012, showed that Bt cotton has increased yields, profits, and living standards of smallholder farmers.[76] The U.S. GM cotton crop was 4.0 million hectares in 2011 the second largest area in the world, the Chinese GM cotton crop was third largest by area with 3.9 million hectares and Pakistan had the fourth largest GM cotton crop area of 2.6 million hectares in 2011.[75] The initial introduction of GM cotton proved to be a success in Australia – the yields were equivalent to the non-transgenic varieties and the crop used much less pesticide to produce (85% reduction).[77] The subsequent introduction of a second variety of GM cotton led to increases in GM cotton production until 95% of the Australian cotton crop was GM in 2009[78] making Australia the country with the fifth largest GM cotton crop in the world.[75] Other GM cotton growing countries in 2011 were Argentina, Myanmar, Burkina Faso, Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, South Africa and Costa Rica.[75]

Cotton has been genetically modified for resistance to glyphosate a broad-spectrum herbicide discovered by Monsanto which also sells some of the Bt cotton seeds to farmers. There are also a number of other cotton seed companies selling GM cotton around the world. About 62% of the GM cotton grown from 1996 to 2011 was insect resistant, 24% stacked product and 14% herbicide resistant.[75]

Cotton has gossypol, a toxin that makes it inedible. However, scientists have silenced the gene that produces the toxin, making it a potential food crop.[79] On 17 October 2018, the USDA deregulated GE low-gossypol cotton.[80][81]

Organic production

Organic cotton is generally understood as cotton from plants not genetically modified and that is certified to be grown without the use of any synthetic agricultural chemicals, such as fertilizers or pesticides.[82] Its production also promotes and enhances biodiversity and biological cycles.[83] In the United States, organic cotton plantations are required to enforce the National Organic Program (NOP). This institution determines the allowed practices for pest control, growing, fertilizing, and handling of organic crops.[84] As of 2007, 265,517 bales of organic cotton were produced in 24 countries, and worldwide production was growing at a rate of more than 50% per year.[85] Organic cotton products are now available for purchase at limited locations. These are popular for baby clothes and diapers; natural cotton products are known to be both sustainable and hypoallergenic.[citation needed]

Pests and weeds

The cotton industry relies heavily on chemicals, such as fertilizers, insecticides and herbicides, although a very small number of farmers are moving toward an organic model of production. Under most definitions, organic products do not use transgenic Bt cotton which contains a bacterial gene that codes for a plant-produced protein that is toxic to a number of pests especially the bollworms. For most producers, Bt cotton has allowed a substantial reduction in the use of synthetic insecticides, although in the long term resistance may become problematic.

Global pest problems

Significant global pests of cotton include various species of bollworm, such as Pectinophora gossypiella. Sucking pests include cotton stainers, the chili thrips, Scirtothrips dorsalis; the cotton seed bug, Oxycarenus hyalinipennis. Defoliators include the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda.

Cotton yield is threatened by the evolution of new biotypes of insects and of new pathogens.[86] Maintaining good yield requires strategies to slow these adversaries' evolution.[86]

North American insect pests

Historically, in North America, one of the most economically destructive pests in cotton production has been the boll weevil. Boll weevils are beetles who ate cotton in the 1950s, that slowed the production of the cotton industry drastically. "This bone pile of short budgets, loss of market share, failing prices, abandoned farms, and the new immunity of boll weevils generated a feeling of helplessness"[87] Boll Weevils first appeared in Beeville, Texas wiping out field after field of cotton in south Texas. This swarm of Boll Weevils swept through east Texas and spread to the eastern seaboard, leaving ruin and devastation in its path, causing many cotton farmers to go out of business.[56]

Due to the US Department of Agriculture's highly successful Boll Weevil Eradication Program (BWEP), this pest has been eliminated from cotton in most of the United States. This program, along with the introduction of genetically engineered Bt cotton, has improved the management of a number of pests such as cotton bollworm and pink bollworm. Sucking pests include the cotton stainer, Dysdercus suturellus and the tarnish plant bug, Lygus lineolaris. A significant cotton disease is caused by Xanthomonas citri subsp. malvacearum.

Harvesting

Most cotton in the United States, Europe and Australia is harvested mechanically, either by a cotton picker, a machine that removes the cotton from the boll without damaging the cotton plant, or by a cotton stripper, which strips the entire boll off the plant. Cotton strippers are used in regions where it is too windy to grow picker varieties of cotton, and usually after application of a chemical defoliant or the natural defoliation that occurs after a freeze. Cotton is a perennial crop in the tropics, and without defoliation or freezing, the plant will continue to grow.

Cotton continues to be picked by hand in developing countries[88] and in Xinjiang, China, allegedly by forced labor.[89] Xinjiang produces over 20% of the world's cotton.[90]

Competition from synthetic fibers

The era of manufactured fibers began with the development of rayon in France in the 1890s. Rayon is derived from a natural cellulose and cannot be considered synthetic, but requires extensive processing in a manufacturing process, and led the less expensive replacement of more naturally derived materials. A succession of new synthetic fibers were introduced by the chemicals industry in the following decades. Acetate in fiber form was developed in 1924. Nylon, the first fiber synthesized entirely from petrochemicals, was introduced as a sewing thread by DuPont in 1936, followed by DuPont's acrylic in 1944. Some garments were created from fabrics based on these fibers, such as women's hosiery from nylon, but it was not until the introduction of polyester into the fiber marketplace in the early 1950s that the market for cotton came under threat.[91] The rapid uptake of polyester garments in the 1960s caused economic hardship in cotton-exporting economies, especially in Central American countries, such as Nicaragua, where cotton production had boomed tenfold between 1950 and 1965 with the advent of cheap chemical pesticides. Cotton production recovered in the 1970s, but crashed to pre-1960 levels in the early 1990s.[92]

Competition from natural fibers

High water and pesticide use in cotton cultivation has prompted sustainability concerns and created a market for natural fiber alternatives. Other cellulose fibers, such as hemp, are seen as more sustainable options because of higher yields per acre with less water and pesticide use than cotton.[93] Cellulose fiber alternatives have similar characteristics but are not perfect substitutes for cotton textiles with differences in properties like tensile strength and thermal regulation.

Uses

Cotton is used to make a number of textile products. These include terrycloth for highly absorbent bath towels and robes; denim for blue jeans; cambric, popularly used in the manufacture of blue work shirts (from which the term "blue-collar" is derived) and corduroy, seersucker, and cotton twill. Socks, underwear, and most T-shirts are made from cotton. Bed sheets often are made from cotton. It is a preferred material for sheets as it is hypoallergenic, easy to maintain and non-irritant to the skin.[94] Cotton also is used to make yarn used in crochet and knitting. Fabric also can be made from recycled or recovered cotton that otherwise would be thrown away during the spinning, weaving, or cutting process. While many fabrics are made completely of cotton, some materials blend cotton with other fibers, including rayon and synthetic fibers such as polyester. It can either be used in knitted or woven fabrics, as it can be blended with elastine to make a stretchier thread for knitted fabrics, and apparel such as stretch jeans. Cotton can be blended also with linen producing fabrics with the benefits of both materials. Linen-cotton blends are wrinkle resistant and retain heat more effectively than only linen, and are thinner, stronger and lighter than only cotton.[95]

In addition to the textile industry, cotton is used in fishing nets, coffee filters, tents, explosives manufacture (see nitrocellulose), cotton paper, and in bookbinding. Fire hoses were once made of cotton.

The cottonseed which remains after the cotton is ginned is used to produce cottonseed oil, which, after refining, can be consumed by humans like any other vegetable oil. The cottonseed meal that is left generally is fed to ruminant livestock; the gossypol remaining in the meal is toxic to monogastric animals. Cottonseed hulls can be added to dairy cattle rations for roughage. During the American slavery period, cotton root bark was used in folk remedies as an abortifacient, that is, to induce a miscarriage. Gossypol was one of the many substances found in all parts of the cotton plant and it was described by the scientists as 'poisonous pigment'. It also appears to inhibit the development of sperm or even restrict the mobility of the sperm. Also, it is thought to interfere with the menstrual cycle by restricting the release of certain hormones.[96]

Cotton linters are fine, silky fibers which adhere to the seeds of the cotton plant after ginning. These curly fibers typically are less than 1⁄8 inch (3.2 mm) long. The term also may apply to the longer textile fiber staple lint as well as the shorter fuzzy fibers from some upland species. Linters are traditionally used in the manufacture of paper and as a raw material in the manufacture of cellulose. In the UK, linters are referred to as "cotton wool".

A less technical use of the term "cotton wool", in the UK and Ireland, is for the refined product known as "absorbent cotton" (or, often, just "cotton") in U.S. usage: fluffy cotton in sheets or balls used for medical, cosmetic, protective packaging, and many other practical purposes. The first medical use of cotton wool was by Sampson Gamgee at the Queen's Hospital (later the General Hospital) in Birmingham, England.

Long staple (LS cotton) is cotton of a longer fibre length and therefore of higher quality, while Extra-long staple cotton (ELS cotton) has longer fibre length still and of even higher quality. The name "Egyptian cotton" is broadly associated high quality cottons and is often an LS or (less often) an ELS cotton.[97] Nowadays the name "Egyptian cotton" refers more to the way cotton is treated and threads produced rather than the location where it is grown. The American cotton variety Pima cotton is often compared to Egyptian cotton, as both are used in high quality bed sheets and other cotton products. While Pima cotton is often grown in the American southwest,[98] the Pima name is now used by cotton-producing nations such as Peru, Australia and Israel.[99] Not all products bearing the Pima name are made with the finest cotton: American-grown ELS Pima cotton is trademarked as Supima cotton.[100] "Kasturi" cotton is a brand-building initiative for Indian long staple cotton by the Indian government. The PIB issued a press release announcing the same.[101][102][103][104][105]

Cottons have been grown as ornamentals or novelties due to their showy flowers and snowball-like fruit. For example, Jumel's cotton, once an important source of fiber in Egypt, started as an ornamental.[106] However, agricultural authorities such as the Boll Weevil Eradication Program in the United States discourage using cotton as an ornamental, due to concerns about these plants harboring pests injurious to crops.[107]

International trade

The largest producers of cotton, as of 2017, are India and China, with annual production of about 18.53 million tonnes and 17.14 million tonnes, respectively; most of this production is consumed by their respective textile industries. The largest exporters of raw cotton are the United States, with sales of $4.9 billion, and Africa, with sales of $2.1 billion. The total international trade is estimated to be $12 billion. Africa's share of the cotton trade has doubled since 1980. Neither area has a significant domestic textile industry, textile manufacturing having moved to developing nations in Eastern and South Asia such as India and China. In Africa, cotton is grown by numerous small holders. Dunavant Enterprises, based in Memphis, Tennessee, is the leading cotton broker in Africa, with hundreds of purchasing agents. It operates cotton gins in Uganda, Mozambique, and Zambia. In Zambia, it often offers loans for seed and expenses to the 180,000 small farmers who grow cotton for it, as well as advice on farming methods. Cargill also purchases cotton in Africa for export.

The 25,000 cotton growers in the United States are heavily subsidized at the rate of $2 billion per year although China now provides the highest overall level of cotton sector support.[108] The future of these subsidies is uncertain and has led to anticipatory expansion of cotton brokers' operations in Africa. Dunavant expanded in Africa by buying out local operations. This is only possible in former British colonies and Mozambique; former French colonies continue to maintain tight monopolies, inherited from their former colonialist masters, on cotton purchases at low fixed prices.[109]

To encourage trade and organize discussion about cotton, World Cotton Day is celebrated every October 7.[110][111][112][105]

Cotton is included within World Trade Organization (WTO) activities within two "complementary tracks":

- trade aspects, around multilateral negotiations aiming to address distorting subsidies and trade barriers affecting cotton; and

- development assistance provided within the cotton production industry and its value chain.[113]

An agreement on trade in cotton formed part of the ministerial declaration concluding the World Trade Organization Ministerial Conference of 2005.[114]

Production

| Country | Production (tonnes) |

|---|---|

| 18,121,818 | |

| 14,990,000 | |

| 8,468,691 | |

| 6,422,030 | |

| 3,500,680 | |

| 2,800,000 | |

| 2,750,000 | |

| 2,409,642 | |

| 1,201,421 | |

| 1,115,510 | |

| 871,955 | |

| 668,633 | |

| 588,110 | |

| 526,000 | |

| 511,996 | |

| 448,573 | |

| 404,800 | |

| 373,018 | |

| 361,819 | |

| 322,471 | |

| 289,488 | |

| World | 69,668,143 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[115] | |

In 2022, world production of cotton was 69.7 million tonnes, led by China with 26% of the total. Other major producers were India (22%) and the United States (12%) (table).

The five leading exporters of cotton in 2019 are (1) India, (2) the United States, (3) China, (4) Brazil, and (5) Pakistan.

In India, the states of Maharashtra (26.63%), Gujarat (17.96%) and Andhra Pradesh (13.75%) and also Madhya Pradesh are the leading cotton producing states,[116] these states have a predominantly tropical wet and dry climate.

In the United States, the state of Texas led in total production as of 2004,[117] while the state of California had the highest yield per acre.[118]

Fair trade

Cotton is an enormously important commodity throughout the world. It provides livelihoods for up to 1 billion people, including 100 million smallholder farmers who cultivate cotton.[119] However, many farmers in developing countries receive a low price for their produce, or find it difficult to compete with developed countries.

This has led to an international dispute (see Brazil–United States cotton dispute):

On 27 September 2002, Brazil requested consultations with the US regarding prohibited and actionable subsidies provided to US producers, users and/or exporters of upland cotton, as well as legislation, regulations, statutory instruments and amendments thereto providing such subsidies (including export credits), grants, and any other assistance to the US producers, users and exporters of upland cotton.[120]

On 8 September 2004, the Panel Report recommended that the United States "withdraw" export credit guarantees and payments to domestic users and exporters, and "take appropriate steps to remove the adverse effects or withdraw" the mandatory price-contingent subsidy measures.[121]

While Brazil was fighting the US through the WTO's Dispute Settlement Mechanism against a heavily subsidized cotton industry, a group of four least-developed African countries – Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, and Mali – also known as "Cotton-4" have been the leading protagonist for the reduction of US cotton subsidies through negotiations. The four introduced a "Sectoral Initiative in Favour of Cotton", presented by Burkina Faso's President Blaise Compaoré during the Trade Negotiations Committee on 10 June 2003.[122]

In addition to concerns over subsidies, the cotton industries of some countries are criticized for employing child labor and damaging workers' health by exposure to pesticides used in production. The Environmental Justice Foundation has campaigned against the prevalent use of forced child and adult labor in cotton production in Uzbekistan, the world's third largest cotton exporter.[123]

The international production and trade situation has led to "fair trade" cotton clothing and footwear, joining a rapidly growing market for organic clothing, fair fashion or "ethical fashion". The fair trade system was initiated in 2005 with producers from Cameroon, Mali and Senegal, with the Association Max Havelaar France playing a lead role in the establishment of this segment of the fair trade system in conjunction with Fairtrade International and the French organisation Dagris (Développement des Agro-Industries du Sud).[124]

Trading

Cotton is bought and sold by investors and price speculators as a tradable commodity on two different commodity exchanges in the United States of America.

- Cotton No. 2 futures contracts are traded on the ICE Futures US Softs (NYI) under the ticker symbol CT. They are delivered every year in March, May, July, October, and December.[125]

- Cotton futures contracts are traded on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) under the ticker symbol TT. They are delivered every year in March, May, July, October, and December.[126]

| Cotton (CTA) | |

|---|---|

| Exchange: | NYI |

| Sector: | Energy |

| Tick size: | 0.01 |

| Tick value: | 5 USD |

| BPV: | 500 |

| Denomination: | USD |

| Decimal place: | 2 |

Critical temperatures

- Favorable travel temperature range: below 25 °C (77 °F)

- Optimum travel temperature: 21 °C (70 °F)

- Glow temperature: 205 °C (401 °F)

- Fire point: 210 °C (410 °F)

- Autoignition temperature: 360–425 °C (680–797 °F)[127]

- Autoignition temperature (for oily cotton): 120 °C (248 °F)

A temperature range of 25 to 35 °C (77 to 95 °F) is the optimal range for mold development. At temperatures below 0 °C (32 °F), rotting of wet cotton stops. Damaged cotton is sometimes stored at these temperatures to prevent further deterioration.[128]

Egypt has a unique climatic temperature that the soil and the temperature provide an exceptional environment for cotton to grow rapidly.

British standard yarn measures

- 1 thread = 55 in or 140 cm

- 1 skein or rap = 80 threads (120 yd or 110 m)

- 1 hank = 7 skeins (840 yd or 770 m)

- 1 spindle = 18 hanks (15,120 yd or 13.83 km)

Fiber properties

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

| Property | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| Shape | Fairly uniform in width, 12–20 micrometers; length varies from 1 cm to 6 cm (1⁄2 to 21⁄2 inches); typical length is 2.2 cm to 3.3 cm (7⁄8 to 11⁄4 inches). |

| Luster | High |

| Tenacity (strength) Dry Wet |

3.0–5.0 g/d 3.3–6.0 g/d |

| Resiliency | Low |

| Density | 1.54–1.56 g/cm3 |

| Moisture absorption raw: conditioned saturation mercerized: conditioned saturation |

8.5% 15–25% 8.5–10.3% 15–27%+ |

| Dimensional stability | Good |

| Resistance to acids alkali organic solvents sunlight microorganisms insects |

Damage, weaken fibers resistant; no harmful effects high resistance to most Prolonged exposure weakens fibers. Mildew and rot-producing bacteria damage fibers. Silverfish damage fibers. |

| Thermal reactions to heat to flame |

Decomposes after prolonged exposure to temperatures of 150 °C or over. Burns readily with yellow flame, smells like burning paper. The residual ash is light and fluffy and greyish in color.[129] |

Depending upon the origin, the chemical composition of cotton is as follows:[130]

- Cellulose 91.00%

- Water 7.85%

- Protoplasm, pectins 0.55%

- Waxes, fatty substances 0.40%

- Mineral salts 0.20%

Morphology

Cotton has a more complex structure among the other crops. A matured cotton fiber is a single, elongated complete dried multilayer cell that develops in the surface layer of cottonseed. It has the following parts.[131]

- The cuticle is the outer most layer. It is a waxy layer that contains pectins and proteinaceous materials.[132]

- The primary wall is the original thin cell wall. Primary wall is mainly cellulose, it is made up of a network of fine fibrils (small strands of cellulose).[132]

- The winding layer is the first layer of secondary thickening it is also called the S1 layer. It is different in structure from both the primary wall and the remainder of the secondary wall. It consists of fibrils aligned at 40 to 70-degree angles to the fiber axis in an open netting type of pattern.[132]

- The secondary wall consists of concentric layers of cellulose it is also called the S2 layer, that constitute the main portion of the cotton fiber. After the fiber has attained its maximum diameter, new layers of cellulose are added to form the secondary wall. The fibrils are deposited at 70 to 80-degree angles to the fiber axis, reversing angle at points along the length of the fiber.[132]

- The lumen is the hollow canal that runs the length of the fiber. It is filled with living protoplasm during the growth period. After the fiber matures and the boll opens, the protoplast dries up, and the lumen naturally collapses, leaving a central void, or pore space, in each fiber. It separates the secondary wall from the lumen and appears to be more resistant to certain reagents than the secondary wall layers. The lumen wall also called the S3 layer.[132][133][131]

Dead cotton

Dead cotton is a term that refers to unripe cotton fibers that do not absorb dye.[134] Dead cotton is immature cotton that has poor dye affinity and appears as white specks on a dyed fabric. When cotton fibers are analyzed and assessed through a microscope, dead fibers appear differently. Dead cotton fibers have thin cell walls. In contrast, mature fibers have more cellulose and a greater degree of cell wall thickening[135]

Genome

This section needs to be updated. (April 2021) |

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (January 2011) |

There is a public effort to sequence the genome of cotton. It was started in 2007 by a consortium of public researchers.[136] Their aim is to sequence the genome of cultivated, tetraploid cotton. "Tetraploid" means that its nucleus has two separate genomes, called A and D. The consortium agreed to first sequence the D-genome wild relative of cultivated cotton (G. raimondii, a Central American species) because it is small and has few repetitive elements. It has nearly one-third of the bases of tetraploid cotton, and each chromosome occurs only once.[clarification needed] Then, the A genome of G. arboreum would be sequenced. Its genome is roughly twice that of G. raimondii. Part of the difference in size is due to the amplification of retrotransposons (GORGE). After both diploid genomes are assembled, they would be used as models for sequencing the genomes of tetraploid cultivated species. Without knowing the diploid genomes, the euchromatic DNA sequences of AD genomes would co-assemble, and their repetitive elements would assemble independently into A and D sequences respectively. There would be no way to untangle the mess of AD sequences without comparing them to their diploid counterparts.

The public sector effort continues with the goal to create a high-quality, draft genome sequence from reads generated by all sources. The effort has generated Sanger reads of BACs, fosmids, and plasmids, as well as 454 reads. These later types of reads will be instrumental in assembling an initial draft of the D genome. In 2010, the companies Monsanto and Illumina completed enough Illumina sequencing to cover the D genome of G. raimondii about 50x.[137] They announced that they would donate their raw reads to the public. This public relations effort gave them some recognition for sequencing the cotton genome. Once the D genome is assembled from all of this raw material, it will undoubtedly assist in the assembly of the AD genomes of cultivated varieties of cotton, but much work remains.

As of 2014, at least one assembled cotton genome had been reported.[138]

See also

- Cotton Belt

- Cotton candy

- Cotton carding

- Cotton gin

- Cotton mill

- The Cotton Museum

- Cotton recycling

- Diplomacy of the American Civil War § Cotton and the British economy

- Environmental impact of fashion

- International Cotton Advisory Committee

- International Cotton Association

- Java cotton (kapok)

- King Cotton

- Madapollam

- Mercerized cotton

- Sea island cotton

References

- ^ The Biology of Gossypium hirsutum L. and Gossypium barbadense L. (cotton). ogtr.gov.au

- ^ "The Evolution of Cotton". Learn.Genetics. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ a b "Natural fibres: Cotton". 2009 International Year of Natural Fibres. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011.

- ^ Liu, Xia; Zhao, Bo; Zheng, Hua-Jun; Hu, Yan; Lu, Gang; Yang, Chang-Qing; Chen, Jie-Dan; Chen, Jun-Jian; Chen, Dian-Yang; Zhang, Liang; Zhou, Yan; Wang, Ling-Jian; Guo, Wang-Zhen; Bai, Yu-Lin; Ruan, Ju-Xin (30 September 2015). "Gossypium barbadense genome sequence provides insight into the evolution of extra-long staple fiber and specialized metabolites". Scientific Reports. 5 (1): 14139. Bibcode:2015NatSR...514139L. doi:10.1038/srep14139. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4588572. PMID 26420475.

- ^ Singh, Phundan. "Cotton Varieties and Hybrids" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ A number of large dictionaries were written in Arabic during medieval times. Searchable copies of nearly all of the main medieval Arabic dictionaries are online at Baheth.info Archived 15 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine and/or AlWaraq.net. One of the most esteemed of the dictionaries is Ismail ibn Hammad al-Jawhari's "Al-Sihah" which is dated around and shortly after year 1000. The biggest is Ibn Manzur's "Lisan Al-Arab" which is dated 1290 but most of its contents were taken from a variety of earlier sources, including 9th- and 10th-century sources. Often Ibn Manzur names his source then quotes from it. Therefore, if the reader recognizes the name of Ibn Manzur's source, a date considerably earlier than 1290 can often be assigned to what is said. A list giving the year of death of a number of individuals who Ibn Manzur quotes from is in Lane's Arabic-English Lexicon, volume 1, page xxx (year 1863). Lane's Arabic-English Lexicon contains much of the main contents of the medieval Arabic dictionaries in English translation. At AlWaraq.net, in addition to searchable copies of medieval Arabic dictionaries, there are searchable copies of a large number of medieval Arabic texts on various subjects.

- ^ More details at CNRTL.fr Etymologie in French language. Centre national de ressources textuelles et lexicales (CNRTL) is a division of the French National Centre for Scientific Research.

- ^ Mazzaoui, Maureen Fennell (1981). The Italian Cotton Industry in the Later Middle Ages, 1100-1600. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23095-7.[page needed]

- ^ "The definition of cotton". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ Mithen, Steven (2006), After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20,000-5000 BC, Harvard University Press, pp. 411–412, ISBN 978-0-674-01999-7 Quote: "One of the funerary chambers, dating to around 5500 BC, had contained an adult male lying on his side with legs flexed backward and a young child, approximately one or two years old, at his feet. Next to the adult's left wrist were eight copper beads which had once formed a bracelet. As such metal beads were only found in one other Neolithic burial at Mehrgarh, he must have been an extraordinarily wealthy and important person. Microscopic analysis showed that each bead had been made by beating and heating copper ore into a thin sheet which had then been rolled around a narrow rod. Substantial corrosion prevented a detailed technological study of the beads; yet this turned out to be a blessing as the corrosion had led to the preservation of something quite remarkable inside one of the beads – a piece of cotton. ... After further microscopic study, the fibres were unquestionably identified as cotton; it was, in fact, a bundle of both unripe and ripe fibres that had been wound together to make a thread, these being differentiated by the thickness of their cell walls. As such, this copper bead contained the earliest known use of cotton in the world by at least a thousand years. The next earliest was also found at Mehrgarh: a collection of cotton seeds discovered amidst charred wheat and barley grains outside one of its mud-brick rooms."

- ^ Moulherat, C.; Tengberg, M.; Haquet, J. R. M. F.; Mille, B. ̂T. (2002). "First Evidence of Cotton at Neolithic Mehrgarh, Pakistan: Analysis of Mineralized Fibres from a Copper Bead". Journal of Archaeological Science. 29 (12): 1393–1401. Bibcode:2002JArSc..29.1393M. doi:10.1006/jasc.2001.0779. Quote: "The metallurgical analysis of a copper bead from a Neolithic burial (6th millennium bc) at Mehrgarh, Pakistan, allowed the recovery of several threads, preserved by mineralization. They were characterized according to new procedure, combining the use of a reflected-light microscope and a scanning electron microscope, and identified as cotton (Gossypium sp.). The Mehrgarh fibres constitute the earliest known example of cotton in the Old World and put the date of the first use of this textile plant back by more than a millennium. Even though it is not possible to ascertain that the fibres came from an already domesticated species, the evidence suggests an early origin, possibly in the Kachi Plain, of one of the Old World cottons.

- ^ Jia, Yinhua; Pan, Zhaoe; He, Shoupu; Gong, Wenfang; Geng, Xiaoli; Pang, Baoyin; Wang, Liru; Du, Xiongming (December 2018). "Genetic diversity and population structure of Gossypium arboreum L. collected in China". Journal of Cotton Research. 1 (1): 11. Bibcode:2018JCotR...1...11J. doi:10.1186/s42397-018-0011-0.

Gossypium arboreum is a diploid species cultivated in the Old World. It was first domesticated near the Indus Valley before 6000 BC (Moulherat et al. 2002).

- ^ Ahmed, Mukhtar (2014). Ancient Pakistan - an Archaeological History: Volume III: Harappan Civilization - the Material Culture. Amazon. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-4959-6643-9.

- ^ Jonathan D. Sauer, Historical Geography of Crop Plants: A Select Roster, Routledge (2017), p. 115

- ^ Huckell, Lisa W. (1993). "Plant Remains from the Pinaleño Cotton Cache, Arizona". Kiva, the Journal of Southwest Anthropology and History. 59 (2): 147–203. JSTOR 30246122.

- ^ Beckert, S. (2014). Chapter one: The Rise of a Global Community. In Empire of Cotton: A global history. essay, Vintage Books.

- ^ New World Cotton, p. 117, at Google Books in Manickam, S.; Prakash, A. H. (2016). "Genetic Improvement of Cotton". Gene Pool Diversity and Crop Improvement. Sustainable Development and Biodiversity. Vol. 10. pp. 105–161. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-27096-8_4. ISBN 978-3-319-27094-4.

- ^ Simon, Matt (8 August 2013). "The Most Bonkers Scientific Theories (Almost) Nobody Believes Anymore". Wired. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

- ^ "cotton" in The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–07.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Islamica Foundation "پنبه". Archived from the original on 30 June 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), Retrieved on 28 February 2009. - ^ "Ancient Egyptian cotton unveils secrets of domesticated crop evolution". www2.warwick.ac.uk. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ a b Yvanez, Elsa; Wozniak, Magdalena M. (30 June 2019). "Cotton in ancient Sudan and Nubia: Archaeological sources and historical implications". Revue d'ethnoécologie (15). doi:10.4000/ethnoecologie.4429. S2CID 198635772.

- ^ G. Mokhtar (1 January 1981). Ancient civilizations of Africa. Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-435-94805-4. Retrieved 19 June 2012 – via Books.google.com.

- ^ a b c d Yvanez, Elsa (2018). "Clothing the Elite? Patterns of Textile Production and Consumption in Ancient Sudan and Nubia". Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae. 31: 81–92. doi:10.23858/FAH31.2018.006.

- ^ Maxwell, Robyn J. (2003). Textiles of Southeast Asia: tradition, trade and transformation (revised ed.). Tuttle Publishing. p. 410. ISBN 978-0-7946-0104-1.

- ^ Roche, Julian (1994). The International Cotton Trade. Cambridge, England: Woodhead Publishing Ltd. p. 5.

- ^ a b Lakwete, Angela (2003). Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-0-8018-7394-2. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016.

- ^ Baber, Zaheer (1996). The Science of Empire: Scientific Knowledge, Civilization, and Colonial Rule in India. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7914-2919-8.

- ^ Pacey, Arnold (1991) [1990]. Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-Year History (First MIT Press paperback ed.). Cambridge MA: The MIT Press.

- ^ Pacey, Arnold (1991) [1990]. Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-Year History (First MIT Press paperback ed.). Cambridge MA: The MIT Press. pp. 23–24.

- ^ Backer, Patricia. "Technology in the Middle Ages". History of Technology. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ Volti, Rudi (1999). "cotton". The Facts on File Encyclopedia of Science, Technology, and Society.

- ^ John F. Richards (1995), The Mughal Empire, page 190 Archived 20 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Karl J. Schmidt (2015), An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History, page 100 Archived 20 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Routledge

- ^ Angus Maddison (1995), Monitoring the World Economy, 1820-1992, OECD, p. 30

- ^ Parthasarathi, Prasannan (2011), Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850, Cambridge University Press, p. 2, ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0

- ^ Richard Maxwell Eaton (1996), The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760, page 202 Archived 27 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine, University of California Press

- ^ Irfan Habib (2011), Economic History of Medieval India, 1200-1500, page 53, Pearson Education

- ^ Irfan Habib (2011), Economic History of Medieval India, 1200-1500, pages 53-54, Pearson Education

- ^ Irfan Habib (2011), Economic History of Medieval India, 1200-1500, page 54, Pearson Education

- ^ Karl Marx (1867). Chapter 16: "Machinery and Large-Scale Industry." Das Kapital.

- ^ Jean Batou (1991). Between Development and Underdevelopment: The Precocious Attempts at Industrialization of the Periphery, 1800-1870. Librairie Droz. p. 181. ISBN 978-2-600-04293-2.

- ^ a b Jean Batou (1991). Between Development and Underdevelopment: The Precocious Attempts at Industrialization of the Periphery, 1800-1870. Librairie Droz. pp. 193–196. ISBN 978-2-600-04293-2.

- ^ a b c d e Broadberry, Stephen N.; Gupta, Bishnupriya (August 2005). "Cotton Textiles and the Great Divergence: Lancashire, India and Shifting Competitive Advantage, 1600-1850". Centre for Economic Policy Research. CEPR Press Discussion Paper No. 5183. SSRN 790866.

- ^ Junie T. Tong (2016), Finance and Society in 21st Century China: Chinese Culture Versus Western Markets, page 151, CRC Press

- ^ John L. Esposito (2004), The Islamic World: Past and Present 3-Volume Set, page 190 Archived 20 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford University Press

- ^ James Cypher (2014). The Process of Economic Development. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-16828-4.

- ^ Bairoch, Paul (1995). Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes. University of Chicago Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-226-03463-8.

- ^ Yule, Henry; Burnell, A. C. (2013). Hobson-Jobson: The Definitive Glossary of British India. Oxford University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-317-25293-1.

- ^ Bowen, H. V. (2013). "British Exports of Raw Cotton from India to China during the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries". In Riello, Giorgio; Roy, Tirthankar (eds.). How India Clothed the World. Brill. pp. 115–137. doi:10.1163/9789047429975_006. ISBN 978-90-474-2997-5. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctv2gjwskd.12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 January 2024.

- ^ "Cottonopolis". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Lowe, J (1854). "A Manchester warehouse". Household Words. 9: 269.

- ^ a b Hughs, S. E.; Valco, T. D.; Williford, J. R. (2008). "100 Years of Cotton Production, Harvesting, and Ginning Systems Engineering: 1907-2007". Transactions of the ASABE. 51 (4): 1187–1198. doi:10.13031/2013.25234.

- ^ (Fisher 1932 pp 154–156)[full citation needed]

- ^ Owsley, Frank Lawrence (1929). "The Confederacy and King Cotton: A Study in Economic Coercion". The North Carolina Historical Review. 6 (4): 371–397. JSTOR 23514836.

- ^ a b c Brown, D. Clayton (2011). King Cotton in Modern America: A Cultural, Political, and Economic History since 1945. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-62846-932-5.[page needed]

- ^ Rupert B. Vance, Human factors in cotton culture; a study in the social geography of the American South (U of North Carolina Press, 1929) online free

- ^ Bartels, Meghan; January 15, Space com Senior Writer |; ET, 2019 11:47am (15 January 2019). "Cotton Seed Sprouts on the Moon's Far Side in Historic First by China's Chang'e 4". Space.com. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Planting Cotton Seeds" Archived 27 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine. cottonspinning.com.

- ^ Wegerich, K. (2002). "Natural drought or human-made water scarcity in Uzbekistan?". Central Asia and the Caucasus. 2: 154–162. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012.

- ^ Pearce, Fred (2004). "9 "A Salty Hell"". Keepers of the Spring. Island Press. pp. 109–122. ISBN 978-1-55963-681-0.

- ^ Chapagain, A. K.; Hoekstra, A. Y.; Savenije, H. H. G.; Gautam, R. (2006). "The water footprint of cotton consumption: An assessment of the impact of worldwide consumption of cotton products on the water resources in the cotton producing countries" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 60 (1): 186–203. Bibcode:2006EcoEc..60..186C. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.11.027. S2CID 154788067. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2023. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ a b Mainguet, Monique; Létolle, René (1998). "Human-made Desertification in the Aral Sea Basin". The Arid Frontier. Springer. pp. 129–145. ISBN 978-0-7923-4227-4.

- ^ a b Waltham, Tony; Sholji, Ihsan (November 2001). "The demise of the Aral Sea - an environmental disaster". Geology Today. 17 (6): 218–228. Bibcode:2001GeolT..17..218W. doi:10.1046/j.0266-6979.2001.00319.x. S2CID 129962159.

- ^ Günaydin, Gizem Karakan; Avinc, Ozan; Palamutcu, Sema; Yavas, Arzu; Soydan, Ali Serkan (2019). "Naturally Colored Organic Cotton and Naturally Colored Cotton Fiber Production". Organic Cotton. Textile Science and Clothing Technology. pp. 81–99. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-8782-0_4. ISBN 978-981-10-8781-3. S2CID 134541586.

- ^ "World Water Week". CottonConnect. 7 July 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ "World Water Day: the cost of cotton in water-challenged India". The Guardian. 20 March 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ Mendelsohn, Mike; Kough, John; Vaituzis, Zigfridais; Matthews, Keith (1 January 2003). "Are Bt crops safe?". Nature Biotechnology. 21 (9): 1003–9. doi:10.1038/nbt0903-1003. PMID 12949561. S2CID 16392889.

- ^ Hellmich, Richard L.; Siegfried, Blair D.; Sears, Mark K.; Stanley-Horn, Diane E.; Daniels, Michael J.; Mattila, Heather R.; Spencer, Terrence; Bidne, Keith G.; Lewis, Leslie C. (9 October 2001). "Monarch larvae sensitivity to Bacillus thuringiensis- purified proteins and pollen". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (21): 11925–11930. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9811925H. doi:10.1073/pnas.211297698. PMC 59744. PMID 11559841.

- ^ Rose, Robyn; Dively, Galen P.; Pettis, Jeff (July 2007). "Effects of Bt corn pollen on honey bees: emphasis on protocol development". Apidologie. 38 (4): 368–377. doi:10.1051/apido:2007022. S2CID 18256663.

- ^ Lang, Susan (25 July 2006). "Seven-year glitch: Cornell warns that Chinese GM cotton farmers are losing money due to 'secondary' pests". Cornell University. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012.

- ^ Wang, Z.; Lin, H.; Huang, J.; Hu, R.; Rozelle, S.; Pray, C. (2009). "Bt Cotton in China: Are Secondary Insect Infestations Offsetting the Benefits in Farmer Fields?". Agricultural Sciences in China. 8: 83–90. doi:10.1016/S1671-2927(09)60012-2.

- ^ Carrington, Damien (13 June 2012) GM crops good for environment, study finds Archived 5 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian, Retrieved 16 June 2012

- ^ Lu y, W. K.; Wu, K.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Desneux, N. (July 2012). "Widespread adoption of Bt cotton and insecticide decrease promotes biocontrol services". Nature. 487 (7407): 362–365. Bibcode:2012Natur.487..362L. doi:10.1038/nature11153. PMID 22722864. S2CID 4415298.

- ^ a b c d e f ISAAA Brief 43-2011: Executive Summary Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2011 Archived 10 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ Kathage, J.; Qaim, M. (2012). "Economic impacts and impact dynamics of Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) cotton in India". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (29): 11652–6. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10911652K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1203647109. PMC 3406847. PMID 22753493.

- ^ Facts & Figures/Natural Resource Management Issues, Biotechnology, 2010. cottonaustralia.com.au.

- ^ Genetically modified plants: Global Cultivation Area Cotton Archived 29 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine GMO Compass, 29 March 2010. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ^ Bourzac, Katherine (21 November 2006) Edible Cotton. MIT Technology Review.

- ^ "USDA Announces Deregulation of GE Low-Gossypol Cotton". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original (website) on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ "Federal Register: Texas A&M AgriLife Research; Determination of Nonregulated Status of Cotton Genetically Engineered for Ultra-low Gossypol Levels in the Cottonseed" (PDF). National Archives and Records Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ CCVT Sustainable Archived 23 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Vineyardteam.org. Retrieved on 27 November 2011.

- ^ "VineYardTeam Econ" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ AMSv1 Archived 6 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Ams.usda.gov. Retrieved on 27 November 2011.

- ^ Organic Cotton Facts. Organic Trade Association.

- ^ a b Al-Khayri, Jameel M.; Jain, S. Mohan; Johnson, Dennis Victor (2019). Industrial and Food Crops. Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies. Vol. 6. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland AG. ISBN 978-3-030-23265-8. OCLC 1124613891.: 32 Gutierrez, Andrew Paul; Ponti, Luigi; Herren, Hans R; Baumgärtner, Johann; Kenmore, Peter E (2015). "Deconstructing Indian cotton: weather, yields, and suicides". Environmental Sciences Europe. 27 (1). Springer Science and Business Media. doi:10.1186/s12302-015-0043-8. ISSN 2190-4707. S2CID 3935402.

- ^ "King_Cotton_in_Modern_America_A_Cultural_Political..._----_(11._"The_Fabric_of_Our_Lives").pdf: ART 2100-01 (95293)". calstatela.instructure.com. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ Murray, Craig (2006). Murder in Samarkand – A British Ambassador's Controversial Defiance of Tyranny in the War on Terror. ISBN 978-1-84596-194-7.

- ^ China's 'tainted' cotton, BBC Newshour, Dec. 15, 2020: "A little further along the same road and workers are still in the fields, twisting and plucking the bolls of white fibre. It is hot, grueling, backbreaking work." See also Ana Nicolaci da Costa (13 November 2019). "Xinjiang cotton sparks concern over 'forced labour' claims". BBC., "UK business 'must wake up' to China's Uighur cotton slaves". BBC. 16 December 2020.

- ^ Davidson, Helen (15 December 2020). "Xinjiang: more than half a million forced to pick cotton, report suggests". The Guardian.

- ^ Fiber History Archived 17 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Teonline.com. Retrieved on 27 November 2011.

- ^ Brockett, Charles D. (1998) Land, Power, and Poverty: Agrarian Transformation and Political Conflict. Westview Press. p. 46. ISBN 0-8133-8695-0.

- ^ Novaković, Milada; Popović, Dušan M.; Mladenović, Nenad; Poparić, Goran B.; Stanković, Snežana B. (September 2020). "Development of comfortable and eco-friendly cellulose based textiles with improved sustainability". Journal of Cleaner Production. 267: 122154. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122154. ISSN 0959-6526. S2CID 219477637.

- ^ "Why choose cotton bedding?". 10 March 2021. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021.

- ^ "What is the difference between cotton and linen?". Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ Perrin, Liese M. (2001). "Resisting Reproduction: Reconsidering Slave Contraception in the Old South". Journal of American Studies. 35 (2): 255–274. doi:10.1017/S0021875801006612. JSTOR 27556967. S2CID 145799076.

- ^ Chapter 5. Extra long staple cotton. cottonguide.org

- ^ McGowan, Joseph Clarence (1960). "XII". History of extra-long staple cottons (M.A.). The University of Arizona. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1003.1154.

- ^ "5.2-Market segments-Extra long staple cotton" Archived 21 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine. cottonguide.org.

- ^ "Supima Cotton - FAQ". Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ "Ginners expected to produce 8-10 lakh bales of 'branded' Kasturi cotton this season". The Indian Express. 7 October 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Today, Telangana (6 August 2021). "Cotton research centres to be set up at Adilabad, Warangal". Telangana Today. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "Indian cotton gets 'Kasturi' branding, logo". The Hindu. 9 October 2020. Archived from the original on 30 July 2023.

- ^ "Kasturi, the first national brand of Indian cotton can fetch at least a 5% price premium: Experts". The Economic Times. 11 October 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ a b "India gets its first ever Brand & Logo for its Cotton on 2nd World Cotton Day – A Historic Day for Indian Cotton!". Press Information Bureau. 7 October 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2021.