Cortisone

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɔːrtɪsoʊn/, /ˈkɔːrtɪzoʊn/ |

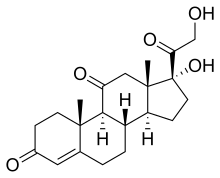

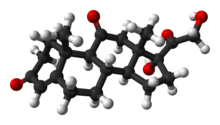

| IUPAC name

17α,21-Dihydroxypregn-4-ene-3,11,20-trione

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(1R,3aS,3bS,9aR,9bS,11aS)-1-Hydroxy-1-(hydroxyacetyl)-9a,11a-dimethyl-2,3,3a,3b,4,5,8,9,9a,9b,11,11a-dodecahydro-7H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene-7,10(1H)-dione | |

| Other names

17α,21-Dihydroxy-11-ketoprogesterone; 17α-Hydroxy-11-dehydrocorticosterone

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.149 |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Cortisone |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C21H28O5 | |

| Molar mass | 360.450 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 220 to 224 °C (428 to 435 °F; 493 to 497 K) |

| Pharmacology | |

| H02AB10 (WHO) S01BA03 (WHO) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Cortisone is a pregnene (21-carbon) steroid hormone. It is a naturally-occurring corticosteroid metabolite that is also used as a pharmaceutical prodrug. Cortisol is converted by the action of the enzyme corticosteroid 11-beta-dehydrogenase isozyme 2 into the inactive metabolite cortisone, particularly in the kidneys. This is done by oxidizing the alcohol group at carbon 11 (in the six-membered ring fused to the five-membered ring). Cortisone is converted back to the active steroid cortisol by stereospecific hydrogenation at carbon 11 by the enzyme 11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1, particularly in the liver.

The term "cortisone" is frequently misused to mean either any corticosteroid or hydrocortisone, which is in fact cortisol. Many who speak of receiving a "cortisone shot" or taking "cortisone" are more likely receiving hydrocortisone or one of many other, much more potent synthetic corticosteroids.

Cortisone can be administered as a prodrug, meaning it has to be converted by the body (specifically the liver, converting it into cortisol) after administration to be effective. It is used to treat a variety of ailments and can be administered intravenously, orally, intra-articularly (into a joint), or transcutaneously. Cortisone suppresses various elements of the immune system, thus reducing inflammation and attendant pain and swelling. Risks exist, in particular in the long-term use of cortisone.[1][2] However, using cortisone only results in very mild activity, and very often more potent steroids are used instead.

Effects and uses

[edit]Cortisone itself is inactive.[3] It must be converted to cortisol by the action of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1.[4] This primarily happens in the liver, the main site at which cortisone becomes cortisol after oral or systemic injection, and can thus have a pharmacological effect. After application to the skin or injection into a joint, local cells that express 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 instead convert it to active cortisol.

A cortisone injection may provide short-term pain relief and may reduce the swelling from inflammation of a joint, tendon, or bursa in, for example, the joints of the knee, elbow and shoulder[1] and into a broken coccyx.[5]

Cortisone is used by dermatologists to treat keloids,[6] relieve the symptoms of eczema and atopic dermatitis,[7] and stop the development of sarcoidosis.[8]

Side effects

[edit]Oral use of cortisone has a number of potential systemic adverse effects, including asthma, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, anxiety, depression, amenorrhoea, cataracts, glaucoma, Cushing's syndrome, increased risk of infections, and impaired growth.[1][2] With topical application, it can lead to thinning of the skin, impaired wound healing, increased skin pigmentation, tendon rupture, and skin infections (including abscesses).[9]

History

[edit]Cortisone was first identified by the American chemists Edward Calvin Kendall and Harold L. Mason while researching at the Mayo Clinic.[10][11][12] During the discovery process, cortisone was known as compound E (while cortisol was known as compound F).

In 1949, Philip S. Hench and colleagues discovered that large doses of injected cortisone were effective in the treatment of patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis.[13] Kendall was awarded the 1950 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine along with Philip Showalter Hench and Tadeusz Reichstein for the discovery of the structure and function of adrenal cortex hormones including cortisone.[14][15] Both Reichstein and the team of O. Wintersteiner and J. Pfiffner had separately isolated the compound prior to the discovery made by Mason and Kendall, but failed to recognize its biological significance.[11] Mason's contributions to the crystallization and characterization of the compound have generally been forgotten outside of the Mayo Clinic.[11]

Cortisone was first produced commercially by Merck & Co. in 1948 or 1949.[13][16] On September 30, 1949, Percy Julian announced an improvement in the process of producing cortisone from bile acids.[17] This eliminated the need to use osmium tetroxide, a rare, expensive, and dangerous chemical. In the UK in the early 1950s, John Cornforth and Kenneth Callow at the National Institute for Medical Research collaborated with Glaxo to produce cortisone from hecogenin from sisal plants.[18]

Production

[edit]Cortisone is one of several end-products of a process called steroidogenesis. This process starts with the synthesis of cholesterol, which then proceeds through a series of modifications in the adrenal gland to become any one of many steroid hormones. One end-product of this pathway is cortisol. For cortisol to be released from the adrenal gland, a cascade of signaling occurs. Corticotropin-releasing hormone released from the hypothalamus stimulates corticotrophs in the anterior pituitary to release ACTH, which relays the signal to the adrenal cortex. Here, the zona fasciculata and zona reticularis, in response to ACTH, secrete glucocorticoids, in particular cortisol. In various peripheral tissues, notably the kidneys, cortisol is inactivated to cortisone by the enzyme corticosteroid 11-beta-dehydrogenase isozyme 2. This is crucial because cortisol is a potent mineralocorticoid and would cause havoc with electrolyte levels (raising blood sodium and lowering blood potassium levels) and raise blood pressure if it were not inactivated in the kidneys.[4]

Because cortisone must be converted to cortisol before being active as a glucocorticoid, its activity is less than simply administering cortisol directly (80–90%).[19]

Popular culture

[edit]Abuse and addiction to cortisone was the subject of the 1956 motion picture Bigger Than Life, produced by and starring James Mason. Though it was a box-office flop upon its initial release,[20] many modern critics hail the film as a masterpiece and brilliant indictment of contemporary attitudes toward mental illness and addiction.[21] However, as of 2024, the combined life-long effects of psychological hopelessness and the physical effects of life-long intractable and unbearable chronic pain that always come with an untreatable and incurable disease has still not been acknowledged. It also must be emphasized that the character Avery did not have any signs on mental illness before his use of cortisone. It was the long-term use, and later abuse, of cortisone that resulted in his psychosis. In 1963, Jean-Luc Godard named it one of the ten greatest American sound films ever made.[22]

John F. Kennedy was regularly administered corticosteroids such as cortisone as a treatment for Addison's disease.[23]

See also

[edit]External links

[edit] Media related to Cortisone at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cortisone at Wikimedia Commons

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c "Cortisone shots". MayoClinic.com. 2010-11-16. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ a b "Prednisone and other corticosteroids: Balance the risks and benefits". MayoClinic.com. 2010-06-05. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ^ Martindale, William; Reynolds, James, eds. (1993). Martindale, The Extra Pharmacopoeia (30th ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. p. 726. ISBN 978-0853693000.

- ^ a b Cooper MS, Stewart PM (2009). "11Beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and its role in the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, metabolic syndrome, and inflammation". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 94 (12): 4645–4654. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-1412. PMID 19837912.

- ^ "injections and needles for coccyx pain". www.coccyx.org.

- ^ Zanon, E; Jungwirth, W; Anderl, H (1992). "Cortisone jet injection as therapy of hypertrophic keloids". Handchirurgie, Mikrochirurgie, Plastische Chirurgie. 24 (2): 100–2. PMID 1582609.

- ^ "All About Atopic Dermatitis". National Eczema Association. Archived from the original on 2012-01-30. Retrieved 2013-05-07.

- ^ Bogart, A.S.; Daniel, D.D.; Poster, K.G. (1954). "Cortisone Treatment of Sarcoidosis". Diseases of the Chest. 26 (2): 224–228. doi:10.1378/chest.26.2.224. PMID 13182965.

- ^ Cole, BJ; Schumacher (Jan–Feb 2005). "Injectable Corticosteroids in Modern Practice". Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 13 (1): 37–46. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.562.1931. doi:10.5435/00124635-200501000-00006. PMID 15712981. S2CID 18658724.

- ^ "Cortisone Discovery and the Nobel Prize". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ^ a b c "I Went to See the Elephant" autobiography of Dwight J. Ingle, published by Vantage Press (1963), pg 94, 109

- ^ Mason, Harold L.; Myers, Charles S.; Kendall, Edward C. (1936). "The chemistry of crystalline substances isolated from the suprarenal gland" (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. 114 (3): 613. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)74790-X. Retrieved 2014-09-07.

- ^ a b Thomas L. Lemke; David A. Williams (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 889–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1950". The Nobel Prize. The Nobel Foundation. 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Glyn, J (1998). "The discovery and early use of cortisone". J R Soc Med. 91 (10): 513–517. doi:10.1177/014107689809101004. PMC 1296908. PMID 10070369.

- ^ Calvert DN (1962). "Anti-inflammatory steroids". Wis. Med. J. 61: 403–4. PMID 13875857.

- ^ Gibbons, Ray (1949). "Science gets synthetic key to rare drug; discovery is made in Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Chicago. p. 1.

- ^ Quirke, Viviane (2005). "Making British Cortisone: Glaxo and the development of Corticosteroids in Britain in the 1950s–1960s". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C. 36 (4): 645–674. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2005.09.001. PMID 16337555.

- ^ "Corticosteroid Dose Equivalents". Medscape. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ Cossar 2011, p. 273.

- ^ Halliwell 2013, pp. 159–162.

- ^ Marshall, Colin (December 2, 2013). "A Young Jean-Luc Godard Picks the 10 Best American Films Ever Made (1963)". Open Culture.

- ^ Altman, Lawrence (October 6, 1992). "The doctor's world; Disturbing Issue of Kennedy's Secret Illness". The New York Times.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bonagura J., DVM; et al. (2000). Current Veterinary Therapy. Vol. 13. pp. 321–381.

- Cossar, Harper (2011). Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-813-12651-7.

- Halliwell, Martin (2013). Therapeutic Revolutions: Medicine, Psychiatry, and American Culture, 1945-1970. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-813-56066-3.

- Ingle DJ (October 1950). "The biologic properties of cortisone: a review". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 10 (10): 1312–54. doi:10.1210/jcem-10-10-1312. PMID 14794756.[permanent dead link]

- Woodward R. B.; Sondheimer F.; Taub D. (1951). "The Total Synthesis of Cortisone". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 73 (8): 4057. doi:10.1021/ja01152a551.