Foreign body

| Foreign body | |

|---|---|

| |

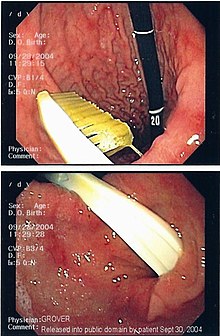

| An endoscopy image of the stomach, showing a foreign body in the form of a toothbrush. | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

A foreign body (FB) is any object originating outside the body of an organism. In machinery, it can mean any unwanted intruding object.

Most references to foreign bodies involve propulsion through natural orifices into hollow organs.

Foreign bodies can be inert or irritating. If they irritate they will cause inflammation and scarring. They can bring infection into the body or acquire infectious agents and protect them from the body's immune defenses. They can obstruct passageways either by their size or by the scarring they cause. Some can be toxic or generate toxic chemicals from reactions with chemicals produced by the body, as is the case with many examples of ingested metal objects.

With sufficient force (as in firing of bullets), a foreign body can become lodged into nearly any tissue.

Gastrointestinal tract

[edit]One of the most common locations for a foreign body is the alimentary tract.

It is possible for foreign bodies to enter the tract from the mouth or rectum.

Both children and adults experience problems caused by foreign objects becoming lodged within their bodies. Young children, in particular, are naturally curious and may intentionally put shiny objects, such as coins or button batteries, into their mouths. They also like to insert objects into their ear canals and nostrils.[1] The severity of a foreign body can range from unconcerning to a life-threatening emergency. For example, a coin causes local pressure on the tissue but generally is not a medical emergency to remove. A button battery, which can be a very similar size to a coin, generates hydroxide ions at the anode and causes a chemical burn in two hours.[2] An ingested button battery that is stuck in the esophagus is a medical emergency. In 2009, Avolio Luigi and Martucciello Giuseppe showed that although ingested nonmagnetic foreign bodies are likely to be passed spontaneously without consequence, ingested magnets (magnetic toys) may attract each other through children's intestinal walls and cause severe damage, such as pressure necrosis, perforation, intestinal fistulas, volvulus, and obstruction.[3]

Pancreas

[edit]Sometimes foreign bodies can pass spontaneously through the gastrointestinal tract and perforate or penetrate the wall of stomach and duodenum and migrate into the pancreas. The laparoscopic approach before open surgery could be performed safely for the removal of foreign bodies embedded in the pancreas.[4]

-

A coin seen on AP CXR in the esophagus

-

A coin seen on lateral CXR in the esophagus

-

AP X ray showing a 9mm battery in the intestines

-

Lateral X ray showing a 9mm battery in the intestines

-

Multiple button batteries in the stomach

Airways

[edit]It is possible for a foreign body to enter the airways and cause choking.[5] A choking case can require the fast usage of basic anti-choking techniques to clear the airway.

In one study, peanuts were the most common obstruction.[6] In addition to peanuts, hot dogs, grapes, and latex balloons are also serious choking hazards in children that can result in death. A latex balloon will conform to the shape of the trachea, blocking the airway and making it difficult to expel with basic anti-choking techniques.[7]

Eyes

[edit]Airborne particles can lodge in the eyes of people at any age. These foreign bodies often result in allergies which are either temporary or even turn into a chronic allergy. This is especially evident in the case of dust particles.

It is also possible for larger objects to lodge in the eye. The most common cause of intraocular foreign bodies is hammering.[8] Corneal foreign bodies are often encountered due to occupational exposure and can be prevented by instituting safety eye-wear at work place.[9]

Foreign bodies in the eye affect about 2 per 1,000 people per year.[10]

Skin

[edit]

Splinters are common foreign bodies in skin. Staphylococcus aureus infection often causes boils to form around them.[11]

Tetanus prophylaxis may be appropriate.[12]

Peritoneum

[edit]Foreign bodies in the peritoneum can include retained surgical instruments after abdominal surgery. Rarely, an intrauterine device can perforate the uterine wall and enter the peritoneum.

Foreign bodies in the peritoneum eventually become contained in a foreign body granuloma. In the extremely rare case of retained ectopic pregnancy, this forms a lithopedion, which involves the fetus being too large to be reabsorbed, and is calcified[13] as a means of shielding the surrounding tissue from infection.

Other

[edit]

Foreign bodies can also become lodged in other locations:

- anus or rectum[14]

- blood vessels or thoracic system[15]

- ears[16]

- nose[17]

- teeth and periodontium[18][19]

- urethra[20]

- vagina[21]

Other animals

[edit]Foreign bodies are common in animals, especially young dogs and cats. Dogs will readily eat toys, bones, and any object that either has food on it or retains the odor of food. Unlike humans, dogs are susceptible to gastrointestinal obstruction due to their ability to swallow relatively large objects and pass them through the esophagus. Foreign bodies most commonly become lodged in the stomach because of the inability to pass through the pyloric sphincter into the jejunum. Symptoms of gastrointestinal obstruction include vomiting, abdominal pain often characterized by aggression, acute infection, and depression due to dehydration.[22] Treatment of a foreign body is determined by its severity. The amount of time a foreign body is present, location of the object, degree of obstruction, previous health status of the animal and the type of material from which the foreign body is made can all determine the severity of the condition. Peritonitis results if either the stomach or intestine has ruptured. Foreign bodies in the stomach can sometimes be removed by endoscopic retrieval or if necessary by gastrotomy.[22] Very often, a simple instrument to remove foreign bodies without operation endoscopy is the Hartmann alligator forceps. The instrument is manufactured from 8 cm to 1 m length. Foreign bodies in the jejunum are removed by enterotomy.

Certain foreign bodies in animals are especially problematic. Bones or objects with sharp edges may cause tearing of the wall of the esophagus, stomach, or small intestine and lead to peritonitis. Pennies swallowed in large numbers may cause zinc poisoning, which in dogs leads to severe gastroenteritis and hemolytic anemia. Linear foreign bodies can especially be dangerous. A linear foreign body is usually a length of string or yarn with a larger object or clump of material at either end. One end is usually lodged in the stomach or proximal small intestine and the other end continues to travel through the intestines. The material becomes tightly stretched and the intestines may "accordion up" on themselves or be lacerated by it. This is especially common in cats who may enjoy playing with a ball of string or yarn. Sometimes the linear foreign body anchors in the mouth by catching under the tongue.[23] Pantyhose is a common linear foreign body in dogs.

-

Bottle top swallowed by a dog

-

Needle swallowed by a cat

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Foreign Bodies: Nose and Paranasal Sinus Disorders: Merck Manual Professional". Archived from the original on 2012-08-26. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ^ Litovitz, Toby. "Swallowed a Button Battery?". National Capital Poison Center. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ Avolio, Luigi; Martucciello, Giuseppe (25 June 2009). "Ingested Magnets". New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (26): 2770. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm0801917. PMID 19553650.

- ^ Mulita, Francesk; Papadopoulos, George; Tsochatzis, Stelios; Kehagias, Ioannis (2020). "Laparoscopic removal of an ingested fish bone from the head of the pancreas: case report and review of literature". Pan African Medical Journal. 36: 123. doi:10.11604/pamj.2020.36.123.23948. PMC 7422735. PMID 32849978.

- ^ "Foreign Body Aspiration: Overview - eMedicine". Archived from the original on 2008-12-27. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ^ Yadav SP, Singh J, Aggarwal N, Goel A (September 2007). "Airway foreign bodies in children: experience of 132 cases" (PDF). Singapore Med J. 48 (9): 850–3. PMID 17728968. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-12-01.

- ^ Muntz, Harlan (2009). Pediatric Otolaryngology for the Clinician: Foreign Body Management. Humana Press. pp. 215–222. ISBN 978-1-58829-542-2.

- ^ "Foreign Body, Intraocular: Overview - eMedicine". Archived from the original on 2008-12-24. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ^ Onkar, Abhishek (2020). "Commentary: Tackling the corneal foreign body". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 68 (1): 57–58. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_1625_19. PMC 6951207. PMID 31856467.

- ^ Ahmed, Faheem; House, Robert James; Feldman, Brad Hal (1 September 2015). "Corneal Abrasions and Corneal Foreign Bodies". Primary Care. 42 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2015.05.004. ISSN 1558-299X. PMID 26319343.

- ^ Fisher, Bruce; Harvey, Richard P.; Champe, Pamela C. (2007). Lippincott's Illustrated Reviews: Microbiology (Lippincott's Illustrated Reviews Series). Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-8215-9.

- ^ Halaas GW (September 2007). "Management of foreign bodies in the skin". Am Fam Physician. 76 (5): 683–8. PMID 17894138.

- ^ Gedam, B.S.; Shah, Yunus; Deshmukh, Shahaji; Bansod, Prasad Y. (2014-12-12). "Skeletal remains of mummified foetus for 36 years in mother's abdomen". International Journal of Surgery Case Reports. 7: 109–111. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.10.074. ISSN 2210-2612. PMC 4336399. PMID 25647606.

- ^ "First Aid & Emergencies: Rectal Foreign Object Treatment". WebMD. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ "Foreign Body Retrieval". RadiologyInfo.org. Archived from the original on 2015-04-13.

- ^ Thompson SK, Wein RO, Dutcher PO (November 2003). "External auditory canal foreign body removal: management practices and outcomes". Laryngoscope. 113 (11): 1912–5. doi:10.1097/00005537-200311000-00010. PMID 14603046. S2CID 21136867.

- ^ "Foreign Body, Nose". Archived from the original on 2008-12-20. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ^ LUCAS RB (1952). "Foreign body reactions in the oral tissues - PubMed". Https. 45 (4): 209–215. PMC 1987454. PMID 14930039.

- ^ Plascencia, H.; Cruz, A.; Solís, R.; Díaz, M.; Vázquez, J. (2014). "Iatrogenic Displacement of a Foreign Body into the Periapical Tissues". Https. 2014: 698538. doi:10.1155/2014/698538. PMC 4244928. PMID 25478244.

- ^ Rahman, N. U.; Elliott, S. P.; McAninch, J. W. (2004). "Self-inflicted male urethral foreign body insertion: endoscopic management and complications". BJU International. 94 (7): 1051–1053. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05103.x. PMID 15541127. S2CID 38657876.

- ^ "Foreign Body, Vagina". Archived from the original on 2008-12-17. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ^ a b "Gastrointestinal Obstruction in Small Animals - Digestive System - Merck Veterinary Manual". Merck Veterinary Manual. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- ^ Glossary Term: Linear Foreign Body Archived 2008-05-17 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- Ingested Magnets. The New England Journal of Medicine.

- The Susy Safe Project. A Surveillance System on Suffocation Injuries due to Foreign Bodies in European Children.