Boycott

| Part of a series on |

| Political revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict some economic loss on the target, or to indicate a moral outrage, usually to try to compel the target to alter an objectionable behavior.

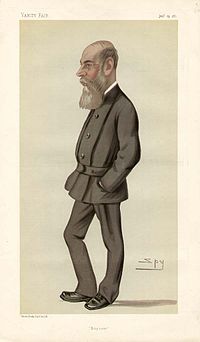

The word is named after Captain Charles Boycott, agent of an absentee landlord in Ireland, against whom the tactic was successfully employed after a suggestion by Irish nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell and his Irish Land League in 1880.

Sometimes, a boycott can be a form of consumer activism, sometimes called moral purchasing. When a similar practice is legislated by a national government, it is known as a sanction. Frequently, however, the threat of boycotting a business is an empty threat, with no significant effect on sales.[1]

Etymology

[edit]

The word boycott entered the English language during the Irish "Land War" and derives from Captain Charles Boycott, the land agent of an absentee landlord, Lord Erne, who lived in County Mayo, Ireland. Captain Boycott was the target of social ostracism organized by the Irish Land League in 1880. As harvests had been poor that year, Lord Erne offered his tenants a ten percent reduction in their rents. In September of that year, protesting tenants demanded a twenty-five percent reduction, which Lord Erne refused. Boycott then attempted to evict eleven tenants from the land. Charles Stewart Parnell, the Irish leader, proposed that when dealing with tenants who take farms where another tenant was evicted, rather than resorting to violence, everyone in the locality should shun them. While Parnell's speech did not refer to land agents or landlords, the tactic was first applied to Boycott when the alarm was raised about the evictions. Despite the short-term economic hardship to those undertaking this action, Boycott soon found himself isolated – his workers stopped work in the fields and stables, as well as in his house. Local businessmen stopped trading with him, and the local postman refused to deliver mail.[2]

The concerted action taken against him meant that Boycott was unable to hire anyone to harvest his crops in his charge.[3] After the harvest, the "boycott" was successfully continued and soon the new word was everywhere. The New-York Tribune reporter, James Redpath, first wrote of the boycott in the international press. The Irish author, George Moore, reported: 'Like a comet the verb 'boycott' appeared.'[4] It was used by The Times in November 1880 as a term for organized isolation. According to an account in the book The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland by Michael Davitt, the term was promoted by Fr. John O'Malley of County Mayo to "signify ostracism applied to a landlord or agent like Boycott". The Times first reported on November 20, 1880: "The people of New Pallas have resolved to 'boycott' them and refused to supply them with food or drink." The Daily News wrote on December 13, 1880: "Already the stoutest-hearted are yielding on every side to the dread of being 'Boycotted'." By January of the following year, the word was being used figuratively: "Dame Nature arose.... She 'Boycotted' London from Kew to Mile End."[5]

Girlcott

[edit]Girlcott, a pun on "boycott", is a boycott intended to focus on the rights or actions of women. The term was coined in 1968 by American Lacey O'Neal during the 1968 Summer Olympics in the context of protests by male African American athletes. The term was later used by retired tennis player Billie Jean King in 1999 in reference to Wimbledon, while discussing equal pay for women players.[6] The term "girlcott" was revived in 2005 by the Women and Girls Foundation in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania against Abercrombie & Fitch.

Notable boycotts

[edit]

Although the term itself was not coined until 1880, the practice dates back to at least the 1790s, when supporters of the British abolitionists led and supported the free produce movement.[7] Other instances include:

- the Iranian Tobacco Boycott in 1891[8]

- Civil rights movement boycotts to protest segregation (e.g., Montgomery & Tallahassee Bus Boycotts)

- the United Farm Workers union grape and lettuce boycotts

- the American boycott of British goods during the American Revolution, such as the Boston Tea Party

- the 1905 Chinese boycott of American products to protest the extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1902.[9]

- the Indian boycott of British goods organized by Mahatma Gandhi

- the successful Jewish boycott organized against Henry Ford in the United States, in the 1920s

- the boycott of Japanese products in China after the May Fourth Movement

- the antisemitic boycott of Jewish-owned businesses in Nazi Germany during the 1930s

- the Jewish anti-Nazi boycott of German goods in Lithuania, the US, Britain, Poland and Mandatory Palestine during 1933

- the Arab League boycott of Israel and companies trading with Israel.

- the worldwide Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign led by Palestinian civil society against the State of Israel.

- The global fossil fuel divestment movement, described by Desmond Tutu as an "apartheid-style boycott to save the planet",[10] and considered to be the biggest boycott-style campaign in history.[11]

- Redundant boycotts along more than one century against Catalan products by Spanish nationalism. Over the years, political/economic claims and self-government milestones, sometimes misrepresented as a secessionist revolt, have often been met with a call for a commercial boycott against Catalonia.[12] This is the case of the creation of the Unió regionalista, the creation of Solidaritat catalana, the ¡Cu-Cut! incident,[13] the Tragic Week (which is advertised as separatist so that it does not spread to other Spanish towns),[14][15][12] creation of the Commonwealth of Catalonia in 1914,[16] the participation of Catalan volunteers in the First World War and claim of the Wilson doctrine for Catalonia,[17] the creation and campaign of the Regionalist League of Catalonia, in 1918,[18][19] autonomy through the Statute of Núria,[20] the Events of 6 October,[21] or, more recently, the Statute of Miravet.[22][23][24] More recently there have been other boycotts related to the expansion of Catalan sovereignty.[25]

During the 1973 oil crisis, the Arab countries enacted a crude oil embargo against the West. Other examples include the US-led boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, the Soviet-led boycott of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, and the movement that advocated "disinvestment" in South Africa during the 1980s in opposition to that country's apartheid regime. The first Olympic boycott was in the 1956 Summer Olympics with several countries boycotting the games for different reasons. Iran also has an informal Olympic boycott against participating against Israel, whereby Iranian athletes typically bow out or claim injuries when pitted against Israelis (see Arash Miresmaeili).

Academic boycotts have been organized against countries—for example, the mid- and late 20th-century academic boycotts of South Africa in protest of apartheid practices and the academic boycotts of Israel in the early 2000s.

Application and uses

[edit]

Boycotts are now much easier to successfully initiate due to the Internet. Examples include the gay and lesbian boycott of advertisers of the Dr. Laura talk show, gun owners' similar boycott of advertisers of Rosie O'Donnell's talk show and (later) magazine, and gun owners' boycott of Smith & Wesson following that company's March 2000 settlement with the Clinton administration. They may be initiated very easily using either websites (the Dr. Laura boycott), newsgroups (the Rosie O'Donnell boycotts), or even mailing lists. Internet-initiated boycotts "snowball" very quickly compared to other forms of organization.

Viral Labeling is a new boycott method using the new digital technology proposed by the Multitude Project and applied for the first time against Walt Disney around Christmas time in 2009.[26]

Some boycotts center on particular businesses, such as recent[when?] protests regarding Costco, Walmart, Ford Motor Company, or the diverse products of Philip Morris. Another form of boycott identifies a number of different companies involved in a particular issue, such as the Sudan Divestment campaign, the "Boycott Bush" campaign. The Boycott Bush website was set up by Ethical Consumer after U.S. President George W. Bush failed to ratify the Kyoto Protocol – the website identified Bush's corporate funders and the brands and products they produce. Historically boycotts have also targeted individual businesses. During the early decades of the twentieth century hotels in Australia were regularly targeted over the cost of alcohol, accommodation and food, as well as mistreatment of employees.[27] Pope Francis refers to boycotting as a successful means of influencing businesses, "forcing them to consider their environmental footprint and their patterns of production".[28]

As a response to consumer boycotts of large-scale and multinational businesses, some companies have marketed brands that do not bear the company's name on the packaging or in advertising. Activists such as Ethical Consumer produce information that reveals which companies own which brands and products so consumers can practice boycotts or moral purchasing more effectively. Another organization, Buycott.com, provides an Internet-based smart-phone application that scans Universal Product Codes and displays corporate relationships to the user.[29]

"Boycotts" may be formally organized by governments as well. In reality, government "boycotts" are just a type of embargo. Notably, the first formal, nationwide act of the Nazi government against German Jews was a national embargo of Jewish businesses on April 1, 1933.[30]

Where the target of a boycott derives all or part of its revenues from other businesses, as a newspaper does, boycott organizers may address the target's commercial customers.

Collective behavior

[edit]The sociology of collective behavior is concerned with causes and conditions pertaining to behavior carried out by a collective, as opposed to an individual (e.g., riots, panics, fads/crazes, boycotts). Boycotts have been characterized by some as different from traditional forms of collective behavior in that they appear to be highly rational and dependent on existing norms and structures. Lewis Killian criticizes that characterization, pointing to the Tallahassee bus boycott as one example of a boycott that aligns with traditional collective behavior theory.[31]

Philip Balsiger points out that political consumption (e.g., boycotts) tends to follow dual-purpose action repertoires, or scripts, which are used publicly to pressure boycott targets and to educate and recruit consumers. Balsiger finds one example in Switzerland, documenting activities of the Clean Clothes Campaign, a public NGO-backed campaign, that highlighted and disseminated information about local companies' ethical practices.[32]

Dixon, Martin, and Nau analyzed 31 collective behavior campaigns against corporations that took place during the 1990s and 2000s. Protests considered successful included boycotts and were found to include a third party, either in the capacity of state intervention or of media coverage. State intervention may make boycotts more efficacious when corporation leaders fear the imposition of regulations. Media intervention may be a crucial contributor to a successful boycott because of its potential to damage the reputation of a corporation. Target corporations that were the most visible were found to be the most vulnerable to either market (protest causing economic loss) or mediated (caused by third-party) disruption. Third-party actors (i.e., the state or media) were more influential when a corporation had a high reputation—when third-party activity was low, highly reputable corporations did not make the desired concessions to boycotters; when third-party activity was high, highly reputable corporations satisfied the demands of boycotters. The boycott, a prima facie market-disruptive tactic, often precipitates mediated disruption. The researchers' analysis led them to conclude that when boycott targets are highly visible and directly interact with and depend on local consumers who can easily find substitutes, they are more likely to make concessions. Koku, Akhigbe, and Springer also emphasize the importance of boycotts' threat of reputational damage, finding that boycotts alone pose more of a threat to a corporation's reputation than to its finances directly.[33][34]

Philippe Delacote points out that a problem contributing to a generally low probability of success for any boycott is the fact that the consumers with the most power to cause market disruption are the least likely to participate; the opposite is true for consumers with the least power. Another collective behavior problem is the difficulty, or impossibility, of direct coordination amongst a dispersed group of boycotters. Yuksel and Mryteza emphasize the collective behavior problem of free riding in consumer boycotts, noting that some individuals may perceive participating to be too great an immediate personal utility sacrifice. They also note that boycotting consumers took the collectivity into account when deciding to participate, that is, consideration of joining a boycott as goal-oriented collective activity increased one's likelihood of participating. A corporation-targeted protest repertoire including boycotts and education of consumers presents the highest likelihood for success.[35][36]

Legality

[edit]

Boycotts are generally legal in developed countries. Occasionally, some restrictions may apply; for instance, in the United States, it may be unlawful for a union to engage in "secondary boycotts" (to request that its members boycott companies that supply items to an organization already under a boycott, in the United States);[37][38] however, the union is free to use its right to speak freely to inform its members of the fact that suppliers of a company are breaking a boycott; its members then may take whatever action they deem appropriate, in consideration of that fact.

United Kingdom

[edit]When the boycott first emerged in Ireland, it presented a serious dilemma for Gladstone's government. The individual actions that constituted a boycott were recognized by legislators as essential to a free society. However, overall a boycott amounted to a harsh, extrajudicial punishment. The Prevention of Crime (Ireland) Act 1882 made it illegal to use "intimidation" to instigate or enforce a boycott, but not to participate in one.[39]

The conservative jurist James Fitzjames Stephen justified laws against boycotting by claiming that the practice amounted to "usurpation of the functions of government" and ought therefore to be dealt with as "the modern representatives of the old conception of high treason".[40]

United States

[edit]

Boycotts are legal under common law. The right to engage in commerce, social intercourse, and friendship includes the implied right not to engage in commerce, social intercourse, and friendship. Since a boycott is voluntary and nonviolent, the law cannot stop it. Opponents of boycotts historically have the choice of suffering under it, yielding to its demands, or attempting to suppress it through extralegal means, such as force and coercion.

In the United States, the antiboycott provisions of the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) apply to all "U.S. persons", defined to include individuals and companies located in the United States and their foreign affiliates. The antiboycott provisions are intended to prevent United States citizens and companies being used as instrumentalities of a foreign government's foreign policy. The EAR forbids participation in or material support of boycotts initiated by foreign governments, for example, the Arab League boycott of Israel. These persons are subject to the law when their activities relate to the sale, purchase, or transfer of goods or services (including the sale of information) within the United States or between the United States and a foreign country. This covers exports and imports, financing, forwarding and shipping, and certain other transactions that may take place wholly offshore.[41]

However, the EAR only applies to foreign government initiated boycotts: a domestic boycott campaign arising within the United States that has the same object as the foreign-government-initiated boycott appears to be lawful, assuming that it is an independent effort not connected with the foreign government's boycott.

Other legal impediments to certain boycotts remain. One set are refusal to deal laws, which prohibit concerted efforts to eliminate competition by refusal to buy from or to sell to a party.[42] Similarly, boycotts may also run afoul of anti-discrimination laws; for example, New Jersey's Law Against Discrimination prohibits any place that offers goods, services and facilities to the general public, such as a restaurant, from denying or withholding any accommodation to (i.e., not to engage in commerce with) an individual because of that individual's race (etc.).[43]

Alternatives

[edit]A boycott is typically a one-time affair intended to correct an outstanding single wrong. When extended for a long period of time, or as part of an overall program of awareness-raising or reforms to laws or regimes, a boycott is part of moral purchasing, and some prefer those economic or political terms. Most organized consumer boycotts today are focused on long-term change of buying habits, and so fit into part of a larger political program, with many techniques that require a longer structural commitment, e.g. reform to commodity markets, or government commitment to moral purchasing, e.g. the longstanding boycott of South African businesses to protest apartheid already alluded to. These stretch the meaning of a "boycott."

Another form of consumer boycotting is substitution for an equivalent product; for example, Mecca Cola and Qibla Cola have been marketed as substitutes for Coca-Cola among Muslim populations.

A prime target of boycotts is consumerism itself, e.g. "International Buy Nothing Day" celebrated globally on the Friday after Thanksgiving Day in the United States.

Another version of the boycott is targeted divestment, or disinvestment. Targeted divestment involves campaigning for withdrawal of investment, for example the Sudan Divestment campaign involves putting pressure on companies, often through shareholder activism, to withdraw investment that helps the Sudanese government perpetuate genocide in Darfur. Only if a company refuses to change its behavior in response to shareholder engagement does the targeted divestment model call for divestment from that company. Such targeted divestment implicitly excludes companies involved in agriculture, the production and distribution of consumer goods, or the provision of goods and services intended to relieve human suffering or to promote health, religious and spiritual activities, or education.

When students are dissatisfied with a political or academic issue, a common tactic for students' unions is to start a boycott of classes (called a student strike among faculty and students since it is meant to resemble strike action by organized labor) to put pressure on the governing body of the institution, such as a university, vocational college or a school, since such institutions cannot afford to have a cohort miss an entire year.

Sports events

[edit]The 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin were held after the Nazis rose to power three years prior. Despite advocacy from numerous officials and activists, no country boycotted the games, although the United States was close to it. In the 1970s and 1980s South Africa became the target of a sports boycott.[44]

After the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the United States led a 66-nation boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics much to Soviet chagrin. The USSR then organized an Eastern Bloc boycott of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, which allowed the Americans to win far more medals than expected.[45]

In at least one case, a boycott has been documented due to on-field results of a game; the residents of New Orleans boycotted television broadcasts of Super Bowl LIII after a controversial officiating call led to the hometown New Orleans Saints losing the NFC Championship Game and being denied a trip to the Super Bowl. Viewership of the game dropped in the city by half compared to Super Bowl LII, contributing to a noticeable drop in the overall national ratings, but the boycott failed to achieve any meaningful remedy for the Saints or their fans.[46]

Diplomatic boycott

[edit]Nations have from time to time used "diplomatic boycotts" to isolate other governments. Following the May Coup of 1903, Great Britain led the major powers in a diplomatic boycott against Serbia, which was a refusal to recognize the post-coup government of Serbia altogether by withdrawing ambassadors and other diplomatic officials from the country;[47] it ended three years later in 1906, when Great Britain renewed diplomatic relations through a decree signed by King Edward VII.[48]

A diplomatic boycott is when diplomatic participation is withheld from an event such as the Olympics but athletic participation is not limited.[49] In 2021, a number of Western nations, led by the United States, Britain and Canada, protested the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics through a diplomatic boycott, citing China's policies concerning the persecution of Uyghurs and human rights violations in the country.[50][51][52]

See also

[edit]- Anti-boycott

- Election boycott

- Group boycott

- International sanctions

- List of boycotts

- Moral purchasing

- No Platform

- Walkout

Notes

[edit]- ^ Chang, Andrea (2021-05-09). "Patagonia shows corporate activism is simpler than it looks". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2021-05-09. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- ^ Marlow, Joyce (1973). Captain Boycott and the Irish. André Deutsch. pp. 133–142. ISBN 978-0-233-96430-0.

- ^ Marlow, pp 157–173.

- ^ Stanford, Jane, That Irishman: the Life and Times of John O'Connor Power, pp. 95–97.

- ^ The Spectator, January 22, 1881.

- ^ A Potential 'Girl-cott' Imperils Grand Slams – Robin Finn, The New York Times, 29 April 1999

- ^ William Fox, An Address to the People of Great Britain, on the Utility of Refraining from the Use of West India Sugar and Rum. 1791

- ^ "Iranian resistance to Tobacco Concession, 1891–1892 | Global Nonviolent Action Database". nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. Retrieved 2024-07-25.

- ^ Jonathan H. X. Lee (2015). Chinese Americans: The History and Culture of a People. ABC-CLIO. p. 26. ISBN 9781610695503.

- ^ Tutu, Desmond (2014-04-10). "We need an apartheid-style boycott to save the planet". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- ^ Vaughan, Adam (2014-10-08). "Fossil fuel divestment: a brief history". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- ^ a b Bosch Cuenca, Pere. "L'amenaça permanent dels boicots". El Punt Avui. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ La Correspondencia militar. «De política. El españolismo y el catalanismo». 4/12/1905, n.º 8.508. Pàg. 3

- ^ Fernández-Cordero Azorín, Concepción. La crisis de 1917. Actitud de la prensa española ante la adjudicación a D. Juan de la Cierva de la cartera de Guerra. Anales de la Universidad de Alicante: Historia contemporánea. DC Heath & Compañia, 1983. p. 183-224.

- ^ Farrés, Andreu. Roses de foc de Barcelona (in Catalan). Edicions 62. ISBN 9788429780925.

- ^ Marimon, Sílvia «El primer intent d'estructura d'estat». Diari Ara, 18-12-2013

- ^ Giovanni E. Cattini. Joaquim de Camps I Arboix. Un intel·lectual en temps convulsos. Fundació Josep Irla. Barcelona. 2015., p.27

- ^ Smith, Angel. La Agonía del liberalismo español. La Lliga Regionalista, la derecha catalana y el nacimiento de la dictadura de Primo de Rivera (1916–1923), 2014, 141–170

- ^ Casals, Xavier (2019-07-14). "Un segle de llaços, ultres i 'indepes' (1919–2019)". El Periódico. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ Casassas Ymbert, Jordi. El catalanismo durante la Segunda República (1931–1939). Bulletin d’Histoire Contemporaine de l’Espagne, 2017, 51: 119–133

- ^ Fernández, David (30 January 2020). "Ai las". La Directa. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ Juliana, Enric. España en el diván. RBA Libros, 2014. ISBN 9788490562277

- ^ Klaus-Jürgen Nagel, amb una aportació de Marició Janué i Miret . Catalunya explicada als alemanys. Les claus per entendre una nació sense estat de l'Europa actual. Cossetània Edicions, 2007. ISBN 9788497912945

- ^ John Tagliabue (13 March 2006). "A War of Words Over Catalonia Sets Off a War of Wine". The New York Times.

- ^ "¿Tiene sentido el boicot a los productos catalanes?". El Confidencial Digital. 7 December 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ "Effective boycott campaigns – Multitude Project". Outreach. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^ McIntyre, Iain (2022-05-02). "Beer Strikes: A History of Hotel Boycotts in Australia, 1900–1920". The Commons Social Change Library. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ^ Pope Francis, Laudato si', paragraph 206, published 24 May 2015, accessed 17 May 2024

- ^ O'Conner, Claire (May 14, 2013). "New App Lets You Boycott Koch Brothers, Monsanto And More By Scanning Your Shopping Cart". Forbes. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

Burner figured the average supermarket shopper had no idea that buying Brawny paper towels, Angel Soft toilet paper or Dixie cups meant contributing cash to Koch Industries through its subsidiary Georgia-Pacific.

- ^ "U.S. Holocaust Museum and Memorial". Outreach. Archived from the original on October 3, 2006. Retrieved January 2, 2007.

- ^ Killian, Lewis M. (1984-01-01). "Organization, Rationality and Spontaneity in the Civil Rights Movement". American Sociological Review. 49 (6): 770–783. doi:10.2307/2095529. JSTOR 2095529.

- ^ Balsiger, Philip (2010-08-01). "Making Political Consumers: The Tactical Action Repertoire of a Campaign for Clean Clothes" (PDF). Social Movement Studies. 9 (3): 311–329. doi:10.1080/14742837.2010.493672. ISSN 1474-2837. S2CID 3335524.

- ^ Dixon, Marc; Martin, Andrew W.; Nau, Michael (2016-04-12). "Social Protest and Corporate Change: Brand Visibility, Third-Party Influence, and the Responsiveness of Corporations to Activist Campaigns *". Mobilization: An International Quarterly. 21 (1): 65–82. doi:10.17813/1086-671x-21-1-65.

- ^ Koku, Paul Sergius; Akhigbe, Aigbe; Springer, Thomas M. (1997-09-01). "The Financial Impact of Boycotts and Threats of Boycott". Journal of Business Research. 40 (1): 15–20. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(96)00279-2.

- ^ Delacote, Philippe (2009-09-01). "On the Sources of Consumer Boycotts Ineffectiveness". The Journal of Environment & Development. 18 (3): 306–322. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1030.5274. doi:10.1177/1070496509338849. ISSN 1070-4965. S2CID 154989034.

- ^ Yuksel, Ulku; Mryteza, Victoria (2009-02-01). "An evaluation of strategic responses to consumer boycotts". Journal of Business Research. Anti-consumption. 62 (2): 248–259. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.01.032.

- ^ National Labor Relations Act, § 8(e), 29 U.S.C.A. § 158(e).

- ^ Local 917, Intern. Broth. of Teamsters v. N.L.R.B., 577 F.3d 70, 75 (C.A.2, 2009).

- ^ Laird 2005, p. 34.

- ^ Laird 2005, p. 36.

- ^ "U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security". Office of Antiboycott Compliance. Archived from the original on March 19, 2006. Retrieved March 20, 2006.

- ^ "Business Dictionary". Archived from the original on 2009-02-03. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

- ^ New Jersey State official website

- ^ Douglas Booth "Hitting apartheid for six? The politics of the South African sports boycott." Journal of Contemporary History 38.3 (2003): 477–493 online.

- ^ Joseph Eaton, . "Reconsidering the 1980 Moscow Olympic boycott: American sports diplomacy in East Asian perspective." Diplomatic History 40.5 (2016): 845–864.

- ^ Scott, Mike (February 4, 2019). "Super Bowl ratings plummet as Who Dats strike back". New Orleans Times-Picayune. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ David McKenzie, "European powers: the diplomatic boycott against Serbia, 1903–1906" in David McKenzie, Serbs and Russians (East European Monographs, 1996) pp 324–341. "diplomatic+boycott+" online

- ^ Slobodan G. Marković. "Kriza u odnosima Kraljevine Srbije i Velike Britanije". NIN. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ^ Hamilton, Tom (10 December 2021). "What, exactly, is a 'diplomatic boycott' of the Beijing Olympics?". espn.com. ESPN. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ Kirby, Jen (10 December 2021). "What the US's diplomatic boycott of the 2022 Beijing Olympics does — and doesn't — mean". vox.com. Vox. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ Roan, Dan (13 December 2021). "How much does the diplomatic boycott of Beijing 2022 matter?". BBC News. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ Allen-Ebrahimian, Bethany; Baker, Kendall (1 February 2022). "The IOC stays silent on human rights in China". Axios.

References

[edit]- Friedman, M. Consumer Boycotts: Effecting Change through the Marketplace and the Media. London: Routledge, 1999.

- Laird, Heather (2005). Subversive Law in Ireland, 1879–1920: from Unwritten Law to Dáil Courts (PDF). Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 9781851828760.

- Hoffmann, S., Müller, S. Consumer Boycotts Due to Factory Relocation. Journal of Business Research, 2009, 62 (2), 239–247.

- Hoffmann, S. Anti-Consumption as a Means of Saving Jobs. European Journal of Marketing, 2011, 45 (11/12), 1702–1714.

- Glickman, Lawrence B. Buying Power: A History of Consumer Activism in America. University Of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Klein, J. G., Smith, N. C., John, A. Why we Boycott: Consumer Motivations for Boycott Participation. Journal of Marketing, 2004, 68 (3), 92–109.