Skull fracture

| Skull fracture | |

|---|---|

| |

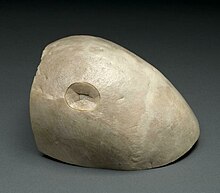

| A piece of a skull with a depressed skull fracture | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

A skull fracture is a break in one or more of the eight bones that form the cranial portion of the skull, usually occurring as a result of blunt force trauma. If the force of the impact is excessive, the bone may fracture at or near the site of the impact and cause damage to the underlying structures within the skull such as the membranes, blood vessels, and brain.

While an uncomplicated skull fracture can occur without associated physical or neurological damage and is in itself usually not clinically significant, a fracture in healthy bone indicates that a substantial amount of force has been applied and increases the possibility of associated injury. Any significant blow to the head results in a concussion, with or without loss of consciousness.

A fracture in conjunction with an overlying laceration that tears the epidermis and the meninges, or runs through the paranasal sinuses and the middle ear structures, bringing the outside environment into contact with the cranial cavity is called a compound fracture. Compound fractures can either be clean or contaminated.

There are four major types of skull fractures: linear, depressed, diastatic, and basilar. Linear fractures are the most common, and usually require no intervention for the fracture itself. Depressed fractures are usually comminuted, with broken portions of bone displaced inward—and may require surgical intervention to repair underlying tissue damage. Diastatic fractures widen the sutures of the skull and usually affect children under three. Basilar fractures are in the bones at the base of the skull.

Types

[edit]Linear fracture

[edit]Linear skull fractures are breaks in the bone that transverse the full thickness of the skull from the outer to inner table. They are usually fairly straight with no bone displacement. The common cause of injury is blunt force trauma where the impact energy transferred over a wide area of the skull.[citation needed]

Linear skull fractures are usually of little clinical significance unless they parallel in close proximity or transverse a suture, or they involve a venous sinus groove or vascular channel. The resulting complications may include suture diastasis, venous sinus thrombosis, and epidural hematoma. In young children, although rare, the possibility exists of developing a growing skull fracture especially if the fracture occurs in the parietal bone.[1]

Depressed fracture

[edit]

A depressed skull fracture is a type of fracture usually resulting from blunt force trauma, such as getting struck with a hammer, rock or getting kicked in the head. These types of fractures—which occur in 11% of severe head injuries—are comminuted fractures in which broken bones displace inward. Depressed skull fractures present a high risk of increased pressure on the brain, or a hemorrhage to the brain that crushes the delicate tissue.[citation needed]

Compound depressed skull fractures occur when there is a laceration over the fracture, putting the internal cranial cavity in contact with the outside environment, increasing the risk of contamination and infection. In complex depressed fractures, the dura mater is torn. Depressed skull fractures may require surgery to lift the bones off the brain if they are pressing on it by making burr holes on the adjacent normal skull.[2]

Diastatic fracture

[edit]

Diastatic fractures occur when the fracture line transverses one or more sutures of the skull causing a widening of the suture. While this type of fracture is usually seen in infants and young children as the sutures are not yet fused it can also occur in adults. When a diastatic fracture occurs in adults it usually affects the lambdoidal suture as this suture does not fully fuse in adults until about the age of 60. Most adult diastatic fractures are caused by severe head injuries. Due to the trauma, diastatic fracture occurs with the collapse of the surrounding head bones. It crushes the delicate tissue, similarly to a depressed skull fracture.[citation needed]

Diastatic fractures can occur with different types of fractures and it is also possible for diastasis of the cranial sutures to occur without a concomitant fracture. Sutural diastasis may also occur in various congenital disorders such as cleidocranial dysplasia and osteogenesis imperfecta.[3][4][5][6]

Basilar fracture

[edit]

Basilar skull fractures are linear fractures that occur in the floor of the cranial vault (skull base), which require more force to cause than other areas of the neurocranium. Thus they are rare, occurring as the only fracture in only 4% of severe head injury patients.

Basilar fractures have characteristic signs: blood in the sinuses; cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea (CSF leaking from the nose) or from the ears (cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea); periorbital ecchymosis often called 'raccoon eyes'[7] (bruising of the orbits of the eyes that result from blood collecting there as it leaks from the fracture site); and retroauricular ecchymosis known as "Battle's sign" (bruising over the mastoid process).[8]

Growing fracture

[edit]A growing skull fracture (GSF) also known as a craniocerebral erosion or leptomeningeal cyst[9] due to the usual development of a cystic mass filled with cerebrospinal fluid is a rare complication of head injury usually associated with linear skull fractures of the parietal bone in children under 3. It has been reported in older children in atypical regions of the skull such as the basioccipital and the base of the skull base and in association with other types of skull fractures. It is characterized by a diastatic enlargement of the fracture.[citation needed]

Various factors are associated with the development of a GSF. The primary causative factor is a tear in the dura mater. The skull fracture enlarges due, in part, to the rapid physiologic growth of the brain that occurs in young children, and brain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pulsations in the underlying leptomeningeal cystic mass.[10][11][12][13][14][15][16]

Cranial burst fracture

[edit]A cranial burst skull fracture, usually occurring with severe injuries in infants less than 1 year of age, is a closed, diastatic skull fracture with cerebral extrusion beyond the outer table of the skull under the intact scalp.[citation needed]

Acute scalp swelling is associated with this type of fracture. In equivocal cases without immediate scalp swelling the diagnosis may be made via the use of magnetic resonance imaging thus insuring more prompt treatment and avoiding the development of a "growing skull fracture".[17]

Compound fracture

[edit]

A fracture in conjunction with an overlying laceration that tears the epidermis and the meninges—or runs through the paranasal sinuses and the middle ear structures, putting the outside environment in contact with the cranial cavity—is a compound fracture.[citation needed]

Compound fractures may either be clean or contaminated. Intracranial air (pneumocephalus) may occur in compound skull fractures.[18]

The most serious complication of compound skull fractures is infection. Increased risk factors for infection include visible contamination, meningeal tear, loose bone fragments and presenting for treatment more than eight hours after initial injury.[19]

Compound elevated fracture

[edit]A compound elevated skull fracture is a rare type of skull fracture where the fractured bone is elevated above the intact outer table of the skull. This type of skull fracture is always compound in nature. It can be caused during an assault with a weapon where the initial blow penetrates the skull and the underlying meninges and, on withdrawal, the weapon lifts the fractured portion of the skull outward. It can also be caused by the skull rotating while being struck in a case of blunt force trauma, the skull rotating while striking an object as in a fall, or it may occur during transfer of a patient after an initial compound head injury.[20][21]

Anatomy

[edit]The human skull is anatomically divided into two parts: the neurocranium, formed by eight cranial bones that houses and protect the brain—and the facial skeleton (viscerocranium) composed of fourteen bones, not including the three ossicles of the inner ear.[22] The term skull fracture typically means fractures to the neurocranium, while fractures of the facial portion of the skull are facial fractures, or if the jaw is fractured, a mandibular fracture.[23]

The eight cranial bones are separated by sutures: one frontal bone, two parietal bones, two temporal bones, one occipital bone, one sphenoid bone, and one ethmoid bone.[24]

The bones of the skull are in three layers: the hard compact layer of the external table (lamina externa), the diploë (a spongy layer of red bone marrow in the middle, and the compact layer of the inner table (Lamina interna).[25]

Skull thickness is variable, depending on location. Thus the traumatic impact required to cause a fracture depends on the impact site. The skull is thick at the glabella, the external occipital protuberance, the mastoid processes, and the external angular process of the frontal bone. Areas of the skull that are covered with muscle have no underlying diploë formation between the internal and external lamina, which results in thin bone more susceptible to fractures.[citation needed]

Skull fractures occur more easily at the thin squamous temporal and parietal bones, the sphenoid sinus, the foramen magnum (the opening at the base of the skull that the spinal cord passes through), the petrous temporal ridge, and the inner portions of the sphenoid wings at the base of the skull. The middle cranial fossa, a depression at the base of the cranial cavity forms the thinnest part of the skull and is thus the weakest part. This area of the cranial floor is weakened further by the presence of multiple foramina; as a result this section is at higher risk for basilar skull fractures to occur. Other areas more susceptible to fractures are the cribriform plate, the roof of orbits in the anterior cranial fossa, and the areas between the mastoid and dural sinuses in the posterior cranial fossa.[26]

Prognosis

[edit]Children with a simple skull fracture without other concerns are at low risk of a bad outcome and rarely require aggressive treatment.[27]

The presence of a concussion or skull fracture in people after trauma without intracranial hemorrhage or focal neurologic deficits was indicated in long term cognitive impairments and emotional lability at nearly double the rate as those patients without either complication.[28]

Those with a skull fracture were shown to have "neuropsychological dysfunction, even in the absence of intracranial pathology or more severe disturbance of consciousness on the GCS".[29]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Haar FL (October 1975). "Complication of linear skull fracture in young children". Am. J. Dis. Child. 129 (10): 1197–200. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1975.02120470047013. PMID 1190143.

- ^ Singh J and Stock A. 2006. "Head Trauma." Emedicine.com. Retrieved on January 26, 2007.

- ^ Paterson CR, Burns J, McAllion SJ (January 1993). "Osteogenesis imperfecta: the distinction from child abuse and the recognition of a variant form". Am. J. Med. Genet. 45 (2): 187–92. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320450208. PMID 8456801.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kanda M, Kabe S, Kanki T, Sato J, Hasegawa Y (December 1997). "[Cleidocranial dysplasia: a case report]". No Shinkei Geka. 25 (12): 1109–13. PMID 9430147.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sabini RC, Elkowitz DE (October 2006). "Significance of differences in patency among cranial sutures". J Am Osteopath Assoc. 106 (10): 600–4. PMID 17122029.

- ^ Pirouzmand F, Muhajarine N (January 2008). "Definition of topographic organization of skull profile in normal population and its implications on the role of sutures in skull morphology". J Craniofac Surg. 19 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e31815ca07a. PMID 18216661. S2CID 7154559.

- ^ Herbella FA, Mudo M, Delmonti C, Braga FM, Del Grande JC (December 2001). "'Raccoon eyes' (periorbital haematoma) as a sign of skull base fracture". Injury. 32 (10): 745–7. doi:10.1016/s0020-1383(01)00144-9. PMID 11754879.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tubbs RS, Shoja MM, Loukas M; et al. (Jan 2010). "William Henry Battle and Battle's sign: mastoid ecchymosis as an indicator of basilar skull fracture". J Neurosurg. 112 (1): 186–8. doi:10.3171/2008.8.JNS08241. PMID 19392601.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Irabor PF, Akhigbe AO (2010). "Leptomeningeal cyst in a child after head trauma: a case report". West Afr J Med. 29 (1): 44–6. PMID 20496339.

- ^ Gupta SK, Reddy NM, Khosla VK; et al. (1997). "Growing skull fractures: a clinical study of 41 patients". Acta Neurochir (Wien). 139 (10): 928–32. doi:10.1007/bf01411301. PMID 9401652. S2CID 24991254.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ersahin Y, Gülmen V, Palali I, Mutluer S (September 2000). "Growing skull fractures (craniocerebral erosion)". Neurosurg Rev. 23 (3): 139–44. doi:10.1007/pl00011945. PMID 11086738. S2CID 22659384.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Muhonen MG, Piper JG, Menezes AH (April 1995). "Pathogenesis and treatment of growing skull fractures". Surg Neurol. 43 (4): 367–72, discussion 372–3. doi:10.1016/0090-3019(95)80066-p. PMID 7792708.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Caffo M, Germanò A, Caruso G, Meli F, Calisto A, Tomasello F (March 2003). "Growing skull fracture of the posterior cranial fossa and of the orbital roof". Acta Neurochir (Wien). 145 (3): 201–8, discussion 208. doi:10.1007/s00701-002-1054-y. PMID 12632116. S2CID 5665654.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ziyal IM, Aydin Y, Türkmen CS, Salas E, Kaya AR, Ozveren F (1998). "The natural history of late diagnosed or untreated growing skull fractures: report on two cases". Acta Neurochir (Wien). 140 (7): 651–4. doi:10.1007/s007010050158. PMID 9781277. S2CID 18879100.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Locatelli D, Messina AL, Bonfanti N, Pezzotta S, Gajno TM (July 1989). "Growing fractures: an unusual complication of head injuries in pediatric patients". Neurochirurgia (Stuttg). 32 (4): 101–4. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1054014. PMID 2770958. S2CID 44468528.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pezzotta S, Silvani V, Gaetani P, Spanu G, Rondini G (1985). "Growing skull fractures of childhood. Case report and review of 132 cases". J Neurosurg Sci. 29 (2): 129–35. PMID 4093801.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Donahue DJ, Sanford RA, Muhlbauer MS, Chadduck WM (December 1995). "Cranial burst fracture in infants: acute recognition and management". Childs Nerv Syst. 11 (12): 692–7. doi:10.1007/BF00262233. PMID 8750951. S2CID 26744592.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fundamentals of diagnostic radiology by William E. Brant, Clyde A. Helms p.56

- ^ Rehman L, Ghani E, Hussain A; et al. (Mar 2007). "Infection in compound depressed fracture of the skull". J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 17 (3): 140–3. PMID 17374298.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Elevated skull fracture[www.ijntonline.com/Dec07/abstracts/abs12.PDF]

- ^ Adeolu AA, Shokunbi MT, Malomo AO, Komolafe EO, Olateju SO, Amusa YB (May 2006). "Compound elevated skull fracture: a forgotten type of skull fracture". Surg Neurol. 65 (5): 503–5. doi:10.1016/j.surneu.2005.07.010. PMID 16630918.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Anne M. Gilroy: : Atlas of Anatomy. P.454; Thime Medical Publishers Inc. (2008) ISBN 1-60406-151-0

- ^ Olson RA, Fonseca RJ, Zeitler DL, Osbon DB (January 1982). "Fractures of the mandible: a review of 580 cases". J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 40 (1): 23–8. doi:10.1016/s0278-2391(82)80011-6. PMID 6950035.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leon Schlossberg, George D. Zuidema, Johns: The Johns Hopkins Atlas of Human Functional Anatomy, p.5; The Johns Hopkins University Press; (1997) ISBN 0-8018-5652-3

- ^ Johannes Lang: Skull base and related structures: atlas of clinical anatomy. P.208. F.K.Schattauer, Germany;(July 1999) ISBN 3-7945-1947-7

- ^ Medscape: Ali Nawaz Khan: Imaging in Skull Fractures [1]

- ^ Bressan, S; Marchetto, L; Lyons, TW; Monuteaux, MC; Freedman, SB; Da Dalt, L; Nigrovic, LE (23 November 2017). "A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Management and Outcomes of Isolated Skull Fractures in Children". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 71 (6): 714–724.e2. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.10.014. PMC 10052777. PMID 29174834. S2CID 205548333.

- ^ Jackson JC, Obremskey W, Bauer R; et al. (January 2007). "Long-term cognitive, emotional, and functional outcomes in trauma intensive care unit survivors without intracranial hemorrhage". J Trauma. 62 (1): 80–8. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31802ce9bd. PMID 17215737.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith-Seemiller L, Lovell MR, Smith S, Markosian N, Townsend RN (March 1997). "Impact of skull fracture on neuropsychological functioning following closed head injury". Brain Inj. 11 (3): 191–6. doi:10.1080/026990597123638. PMID 9058000.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Bibliography

[edit]- Forensic Neuropathology By Jan E. Leestma Publisher: CRC Press; 2 edition (October 14, 2008) Language: English ISBN 0-8493-9167-9 ISBN 978-0849391675

- Neuroimaging: Clinical and Physical Principles By Robert A. Zimmerman, Wendell A. Gibby, Raymond F. Carmody Publisher: Springer; 1st edition (January 15, 2000) Language: English ISBN 0387949631 ISBN 978-0-387-94963-5