Yoga in advertising

Yoga in advertising is the use of images of modern yoga as exercise to market products of any kind, whether related to yoga or not. Goods sold in this way have included canned beer, fast food and computers.

Yoga is an ancient meditational spiritual practice from India, with the goal of the isolation of the self. This goal was replaced with modern goals like good health. Yoga itself was transformed into a form of exercise in India early in the 20th century, and adopted across the Western world for mass consumption. From the 1980s, the yoga market grew and diversified; established yoga brands such as Iyengar Yoga were joined by newer brands like Anusara Yoga. Yoga has become a physical activity mainly for women, and is marketed mainly to them.

The purpose of using yoga in advertising ranges from giving a favourable impression of a product or service, to selling specific yoga-related items like classes, clothing and props. Some such uses, such as of religious symbols like the sacred syllable Om, have been described as cultural appropriation. Yoga advertisements employ themes such as the sexual objectification of women, self-transformation through physical means, and the promise of reduced stress. Images of women in difficult yoga poses feature in advertisements to convey desirable qualities.

Context

[edit]Yoga is an ancient meditational spiritual practice from India. Its goal, detachment from the self or kaivalya, was replaced by the self-affirming goals of good health, reduced stress, and physical flexibility.[2] In the early 20th century, it was transformed through Western influences and a process of innovation in India to become an exercise practice.[3] Around the 1960s, modern yoga was transformed further by three global changes: Westerners were able to travel to India, and Indians were able to migrate to the West; people in the West became disillusioned with organised religion, and started to look for alternatives; and yoga became an uncontroversial form of exercise suitable for mass consumption.[4]

Yoga marketing

[edit]

The growth of yoga as exercise from the 1980s to the 2000s encouraged the market to diversify, first-generation yoga brands such as Iyengar Yoga being joined by second-generation brands such as Anusara Yoga. The scholar of yoga Andrea Jain writes that these were "mass-marketed to the general populace"; successful brands were able to gain audiences of hundreds of thousands from cities around the world.[6] This in turn led to regulation. Professional organisations such as the Yoga Alliance and the European Union of Yoga maintain registries of yoga schools that provide appropriate yoga teacher training, and of yoga teachers who have been trained on approved courses.[7][8] Certifying organisations such as Yoga Alliance have set out guidelines for how their members and others may use their logos in advertisements.[9]

In the Western world, yoga has become "feminized ... both in theory and in practice".[10] Its practitioners are largely women; for example, in the United States in 2004, 77 per cent of yoga practitioners were women, while in Australia in 2002, the figure was 86 per cent;[11] in Britain in the 1970s, yoga classes were between 70 and 90 percent female.[12] Commercialization has gone hand-in-hand with this trend, to the point where yoga aimed at the female market has become a business worth hundreds of millions of pounds a year. Accordingly, advertisers have attempted to appeal to women in search of well-being to market a wide variety of goods and services, some clearly related to a healthy life, from probiotic yoghurt and low-fat cereals to fitness clubs and water filters, and some not, with products as diverse as air travel, beer, motor vehicles, and financial services.[13] Some uses of yoga in marketing, such as for Lululemon yoga clothing and mala beads (with the corporate logo) are seen to be commercial but are at least directly connected to yoga practice.[5]

Other uses, for products unrelated to yoga, have been described as ranging from "offensive" to "just plain bizarre", with the Hindu god Shiva depicted on beer cans, the sacred syllable Om in marketing materials, and a foldable computer named "Yoga".[5][14] The yoga teacher and studio owner Arundhati Baitmangalkar, writing in Yoga International, describes some of this marketing as cultural appropriation. She identifies yoga studios, yoga teachers and yoga-related businesses as among those misusing yoga, stating that sacred symbols like idols of Buddha, Ganesha, Patanjali, and Shiva need to be treated with "reverence", just as the Om symbol, yoga sutras, and mandalas are not "décor" and that they should not be added "casually" to beautify a yoga space.[1] On the other hand, the first-generation Indian American yoga researcher and teacher, Rina Deshpande, writes that people from India can feel excluded if Indian words and symbols are forbidden in an attempt to make yoga classes more inclusive. Deshpande notes that it is ironic that yoga is now "often marketed by affluent Westerners to affluent Westerners—and Indians, ironically, are marginally represented, if at all."[15]

The Welsh author Holly Williams, writing about the commercialisation of yoga in The Independent, commented that she had "unfollowed people on Instagram whose artful shots of their Lycra-clad one-legged wheel poses come with a barrage of hashtags (#fitspo #yogaeverydamnday #beagoddess)."[16]

Themes

[edit]

The feminist scholar Diana York Blaine identifies three themes in the use of yoga in advertising: that the "chaotic female body and its desires" need to be controlled; that consumers can use yoga to "maintain the excesses of patriarchal capitalist consumer culture"; and that the values of Western consumerism and materialism take precedence over the values of Eastern spirituality. In Blaine's view, yoga's appearance in advertising places women in the male gaze: yoga is sold as a way of making the female body perfect enough to gain male approval. Women do often report that they are happier with their bodies with regular yoga, even though, Blaine remarks, yoga's representation in advertising encourages women to be unhappy with their appearance.[10] She gives as example an advertisement by Carl's Jr., a fast food business, in which a woman doing Upward Dog pose confides to her friend that her husband wants her to "get great buns". Blaine explains that this is a pun on the firm's hamburger buns and a slang word for buttocks; this is emphasized by a close-up shot of the women's buttocks, now in Downward Dog, which Blaine describes as objectifying the female body.[10]

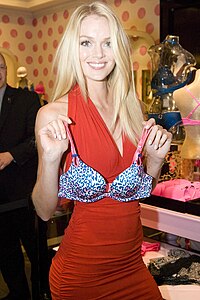

The lingerie of Victoria's Secret, too, has been marketed using yoga. In a 2013 campaign, the model Lindsay Ellingson is shown at an Equinox Health Club gym – advertising that product at the same time – doing Tree Pose and other asanas, with a voiceover telling women "If you want a toned tummy and legs like a Victoria's Secret model, try the Downward Dog". Blaine comments that the marketing is offering "self-transformation through physical, not spiritual, change".[10]

A different approach was taken by Hyatt Hotels, using yoga to sell the brand to businesswomen. In an advertisement, a businesswoman with a stressful family life is seen floating in space on her yoga mat, seated in lotus pose, with the caption "And now the only thing I've left behind is stress". Commenting on the sexism implicit in the scene, Blaine states that "Corporate America increasingly co-opts yoga to keep its army of workers working".[10]

-

"Lycra-clad one-legged wheel poses":[16] Eka Pada Urdhva Dhanurasana performed by a Lululemon yoga model

-

Yoga has been used to sell lingerie. A 2013 campaign featuring Lindsay Ellingson promised women the body of a Victoria's Secret model.[10]

-

Businesses that sell yoga-related products have used Eka Pada Rajakapotasana, as here by Lululemon in 2011

References

[edit]- ^ a b Baitmangalkar, Arundhati. "How We Can Work Together to Avoid Cultural Appropriation in Yoga". Yoga International. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Strauss, Sarah (2005). Positioning Yoga: balancing acts across cultures. Berg. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-85973-739-2. OCLC 290552174.

- ^ Jain, Andrea R. (2012). "The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga". Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies. 25 (1). Butler University, Irwin Library. doi:10.7825/2164-6279.1510.

- ^ Jain, Andrea (2015). Selling Yoga: from Counterculture to Pop culture. Oxford University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-19-939024-3. OCLC 878953765.

- ^ a b c McLellan, Lea (28 January 2015). "Yoga in Advertising: Taking a Bite of the Yoga Pie". Yoga Basics. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Jain 2015, pp. 73–94 "Branding Yoga".

- ^ Jain 2015, p. 96.

- ^ Mullins, Daya. "Yoga and Yoga Therapy in Germany Today" (PDF). Weg Der Mitte. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ "Using The Yoga Alliance Professionals Logo". Yoga Alliance. 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Blaine, Diana York (2016). "Mainstream Representations of Yoga: Capitalism, Consumerism, and Control of the Female Body". In Berila, Beth; Klein, Melanie; Roberts, Chelsea Jackson (eds.). Yoga, the Body, and Embodied Social Change: An Intersectional Feminist Analysis. Lexington Books. pp. 130–140. ISBN 9781498528030.

- ^ Hodges, Julie (2007). The Practice of Iyengar Yoga by Mid-Aged Women: An Ancient Tradition in a Modern Life (PDF) (PhD thesis). Newcastle, New South Wales: University of Newcastle. pp. 66–67. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ Newcombe, Suzanne (2007). "Stretching for Health and Well-Being: Yoga and Women in Britain, 1960–1980". Asian Medicine. 3 (1): 37–63. doi:10.1163/157342107X207209.

- ^ Lane, Megan (9 October 2003). "The Tyranny of Yoga". BBC News. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Davidson, John (27 May 2014). "Not bending over backwards for a Lenovo ThinkPad Yoga". Financial Review. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Deshpande, Rina (1 May 2019). "What's the Difference Between Cultural Appropriation and Cultural Appreciation?". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ a b Williams, Holly (29 November 2015). "The great hippie hijack: how consumerism devoured the counterculture dream". The Independent. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

!["Lycra-clad one-legged wheel poses":[16] Eka Pada Urdhva Dhanurasana performed by a Lululemon yoga model](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/74/Lululemon_Yellow_Yoga.jpg/200px-Lululemon_Yellow_Yoga.jpg)