Scramjet

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Aircraft propulsion |

|---|

|

Shaft engines: driving propellers, rotors, ducted fans or propfans |

| Reaction engines |

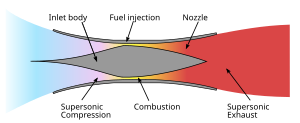

A scramjet (supersonic combustion ramjet) is a variant of a ramjet airbreathing jet engine in which combustion takes place in supersonic airflow. As in ramjets,[1] a scramjet relies on high vehicle speed to compress the incoming air forcefully before combustion (hence ramjet), but whereas a ramjet decelerates the air to subsonic velocities before combustion using shock cones, a scramjet has no shock cone and slows the airflow using shockwaves produced by its ignition source in place of a shock cone.[2] This allows the scramjet to operate efficiently at extremely high speeds.[3]

Although scramjet engines have been used in a handful of operational military vehicles, scramjets have so far mostly been demonstrated in research test articles and experimental vehicles.

History

[edit]Before 2000

[edit]The Bell X-1 attained supersonic flight in 1947 and, by the early 1960s, rapid progress toward faster aircraft suggested that operational aircraft would be flying at "hypersonic" speeds within a few years. Except for specialized rocket research vehicles like the North American X-15 and other rocket-powered spacecraft, aircraft top speeds have remained level, generally in the range of Mach 1 to Mach 3.

During the US aerospaceplane program, between the 1950s and the mid 1960s, Alexander Kartveli and Antonio Ferri were proponents of the scramjet approach.

In the 1950s and 1960s, a variety of experimental scramjet engines were built and ground tested in the US and the UK. Antonio Ferri successfully demonstrated a scramjet producing net thrust in November 1964, eventually producing 517 pounds-force (2.30 kN), about 80% of his goal. In 1958, an analytical paper discussed the merits and disadvantages of supersonic combustion ramjets.[4] In 1964, Frederick S. Billig and Gordon L. Dugger submitted a patent application for a supersonic combustion ramjet based on Billig's PhD thesis. This patent was issued in 1981 following the removal of an order of secrecy.[5]

In 1981, tests were made in Australia under the guidance of Professor Ray Stalker in the T3 ground test facility at ANU.[6]

The first successful flight test of a scramjet was performed as a joint effort with NASA, over the Soviet Union in 1991. It was an axisymmetric hydrogen-fueled dual-mode scramjet developed by Central Institute of Aviation Motors (CIAM), Moscow in the late 1970s, but modernized with a FeCrAl alloy on a converted SM-6 missile to achieve initial flight parameters of Mach 6.8, before the scramjet flew at Mach 5.5. The scramjet flight was flown captive-carry atop the SA-5 surface-to-air missile that included an experimental flight support unit known as the "Hypersonic Flying Laboratory" (HFL), "Kholod".[7]

Then, from 1992 to 1998, an additional six flight tests of the axisymmetric high-speed scramjet-demonstrator were conducted by CIAM together with France and then with NASA.[8][9] Maximum flight speed greater than Mach 6.4 was achieved and scramjet operation during 77 seconds was demonstrated. These flight test series also provided insight into autonomous hypersonic flight controls.

2000s

[edit]

In the 2000s, significant progress was made in the development of hypersonic technology, particularly in the field of scramjet engines.

The HyShot project demonstrated scramjet combustion on 30 July 2002. The scramjet engine worked effectively and demonstrated supersonic combustion in action. However, the engine was not designed to provide thrust to propel a craft. It was designed more or less as a technology demonstrator.[10]

A joint British and Australian team from UK defense company Qinetiq and the University of Queensland were the first group to demonstrate a scramjet working in an atmospheric test.[11]

Hyper-X claimed the first flight of a thrust-producing scramjet-powered vehicle with full aerodynamic maneuvering surfaces in 2004 with the X-43A.[12][13] The last of the three X-43A scramjet tests achieved Mach 9.6 for a brief time.[14]

On 15 June 2007, the US Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA), in cooperation with the Australian Defence Science and Technology Organisation (DSTO), announced a successful scramjet flight at Mach 10 using rocket engines to boost the test vehicle to hypersonic speeds.[15][16]

A series of scramjet ground tests was completed at NASA Langley Arc-Heated Scramjet Test Facility (AHSTF) at simulated Mach 8 flight conditions. These experiments were used to support HIFiRE flight 2.[17]

On 22 May 2009, Woomera hosted the first successful test flight of a hypersonic aircraft in HIFiRE (Hypersonic International Flight Research Experimentation). The launch was one of ten planned test flights. The series of flights is part of a joint research program between the Defence Science and Technology Organisation and the US Air Force, designated as the HIFiRE.[18] HIFiRE is investigating hypersonics technology and its application to advanced scramjet-powered space launch vehicles; the objective is to support the new Boeing X-51 scramjet demonstrator while also building a strong base of flight test data for quick-reaction space launch development and hypersonic "quick-strike" weapons.[18]

2010s

[edit]On 22 and 23 March 2010, Australian and American defense scientists successfully tested a (HIFiRE) hypersonic rocket. It reached an atmospheric speed of "more than 5,000 kilometres per hour" (Mach 4) after taking off from the Woomera Test Range in outback South Australia.[19][20]

On 27 May 2010, NASA and the United States Air Force successfully flew the X-51A Waverider for approximately 200 seconds at Mach 5, setting a new world record for flight duration at hypersonic airspeed.[21] The Waverider flew autonomously before losing acceleration for an unknown reason and destroying itself as planned. The test was declared a success. The X-51A was carried aboard a B-52, accelerated to Mach 4.5 via a solid rocket booster, and then ignited the Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne scramjet engine to reach Mach 5 at 70,000 feet (21,000 m).[22] However, a second flight on 13 June 2011 was ended prematurely when the engine lit briefly on ethylene but failed to transition to its primary JP-7 fuel, failing to reach full power.[23]

On 16 November 2010, Australian scientists from the University of New South Wales at the Australian Defence Force Academy successfully demonstrated that the high-speed flow in a naturally non-burning scramjet engine can be ignited using a pulsed laser source.[24]

A further X-51A Waverider test failed on 15 August 2012. The attempt to fly the scramjet for a prolonged period at Mach 6 was cut short when, only 15 seconds into the flight, the X-51A craft lost control and broke apart, falling into the Pacific Ocean north-west of Los Angeles. The cause of the failure was blamed on a faulty control fin.[25]

In May 2013, an X-51A Waverider reached 4828 km/h (Mach 3.9) during a three-minute flight under scramjet power. The WaveRider was dropped at 50,000 feet (15,000 m) from a B-52 bomber, and then accelerated to Mach 4.8 by a solid rocket booster which then separated before the WaveRider's scramjet engine came into effect.[26]

On 28 August 2016, the Indian space agency ISRO conducted a successful test of a scramjet engine on a two-stage, solid-fueled rocket. Twin scramjet engines were mounted on the back of the second stage of a two-stage, solid-fueled sounding rocket called Advanced Technology Vehicle (ATV), which is ISRO's advanced sounding rocket. The twin scramjet engines were ignited during the second stage of the rocket when the ATV achieved a speed of 7350 km/h (Mach 6) at an altitude of 20 km. The scramjet engines were fired for a duration of about 5 seconds.[27][28]

On 12 June 2019, India successfully conducted the maiden flight test of its indigenously developed uncrewed scramjet demonstration aircraft for hypersonic speed flight from a base from Abdul Kalam Island in the Bay of Bengal at about 11:25 am. The aircraft is called the Hypersonic Technology Demonstrator Vehicle. The trial was carried out by the Defence Research and Development Organisation. The aircraft forms an important component of the country's programme for development of a hypersonic cruise missile system.[29][30]

2020s

[edit]On 27 September 2021, DARPA announced successful flight of its Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept scramjet cruise missile.[31] Another successful test was carried out in mid-March 2022 amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Details were kept secret to avoid escalating tension with Russia, only to be revealed by an unnamed Pentagon official in early April.[32][33]

Design principles

[edit]Scramjet engines are a type of jet engine, and rely on the combustion of fuel and an oxidizer to produce thrust. Similar to conventional jet engines, scramjet-powered aircraft carry the fuel on board, and obtain the oxidizer by the ingestion of atmospheric oxygen (as compared to rockets, which carry both fuel and an oxidizing agent). This requirement limits scramjets to suborbital atmospheric propulsion, where the oxygen content of the air is sufficient to maintain combustion.

The scramjet is composed of three basic components: a converging inlet, where incoming air is compressed; a combustor, where gaseous fuel is burned with atmospheric oxygen to produce heat; and a diverging nozzle, where the heated air is accelerated to produce thrust.[34] Unlike a typical jet engine, such as a turbojet or turbofan engine, a scramjet does not use rotating, fan-like components to compress the air; rather, the achievable speed of the aircraft moving through the atmosphere causes the air to compress within the inlet.[34] As such, no moving parts are needed in a scramjet. In comparison, typical turbojet engines require multiple stages of rotating compressor rotors, and multiple rotating turbine stages, all of which add weight, complexity, and a greater number of failure points to the engine.

Due to the nature of their design, scramjet operation is limited to near-hypersonic velocities. As they lack mechanical compressors, scramjets require the high kinetic energy of a hypersonic flow to compress the incoming air to operational conditions. Thus, a scramjet-powered vehicle must be accelerated to the required velocity (usually about Mach 4) by some other means of propulsion, such as turbojet, or rocket engines.[35] In the flight of the experimental scramjet-powered Boeing X-51A, the test craft was lifted to flight altitude by a Boeing B-52 Stratofortress before being released and accelerated by a detachable rocket to near Mach 4.5.[36] In May 2013, another flight achieved an increased speed of Mach 5.1.[37]

While scramjets are conceptually simple, actual implementation is limited by extreme technical challenges. Hypersonic flight within the atmosphere generates immense drag, and temperatures found on the aircraft and within the engine can be much greater than that of the surrounding air. Maintaining combustion in the supersonic flow presents additional challenges, as the fuel must be injected, mixed, ignited, and burned within milliseconds. While scramjet technology has been under development since the 1950s, only very recently have scramjets successfully achieved powered flight.[38]

Scramjets are designed to operate in the hypersonic flight regime, beyond the reach of turbojet engines, and, along with ramjets, fill the gap between the high efficiency of turbojets and the high speed of rocket engines. Turbomachinery-based engines, while highly efficient at subsonic speeds, become increasingly inefficient at transonic speeds, as the compressor rotors found in turbojet engines require subsonic speeds to operate. While the flow from transonic to low supersonic speeds can be decelerated to these conditions, doing so at supersonic speeds results in a tremendous increase in temperature and a loss in the total pressure of the flow. Around Mach 3–4, turbomachinery is no longer useful, and ram-style compression becomes the preferred method.[39]

Ramjets use high-speed characteristics of air to literally 'ram' air through an inlet diffuser into the combustor. At transonic and supersonic flight speeds, the air upstream of the inlet is not able to move out of the way quickly enough, and is compressed within the diffuser before being diffused into the combustor. Combustion in a ramjet takes place at subsonic velocities, similar to turbojets but the combustion products are then accelerated through a convergent-divergent nozzle to supersonic speeds. As they have no mechanical means of compression, ramjets cannot start from a standstill, and generally do not achieve sufficient compression until supersonic flight. The lack of intricate turbomachinery allows ramjets to deal with the temperature rise associated with decelerating a supersonic flow to subsonic speeds. However, as speed rises, the internal energy of the flow after diffusor grows rapidly, so the relative addition of energy due to fuel combustion becomes lower, leading to decrease in efficiency of the engine. This leads to decrease in thrust generated by ramjets at higher speeds. [39]

Thus, to generate thrust at very high velocities, the rise of the pressure and temperature of the incoming air flow must be tightly controlled. In particular, this means that deceleration of the airflow to subsonic speed cannot be allowed. Mixing the fuel and air in this situation presents a considerable engineering challenge, compounded by the need to closely manage the speed of combustion while maximizing the relative increase of internal energy within the combustion chamber. Consequently, current scramjet technology requires the use of high-energy fuels and active cooling schemes to maintain sustained operation, often using hydrogen and regenerative cooling techniques.[40]

Theory

[edit]All scramjet engines have an intake which compresses the incoming air, fuel injectors, a combustion chamber, and a divergent thrust nozzle. Sometimes engines also include a region which acts as a flame holder, although the high stagnation temperatures mean that an area of focused waves may be used, rather than a discrete engine part as seen in turbine engines. Other engines use pyrophoric fuel additives, such as silane, to avoid flameout. An isolator between the inlet and combustion chamber is often included to improve the homogeneity of the flow in the combustor and to extend the operating range of the engine.

Shockwave imaging by the University of Maryland using Schlieren imaging determined that the fuel mixture controls compression by creating backpressure and shockwaves that slow and compress the air before ignition, much like the shock cone of a Ramjet. The imaging showed that the higher the fuel flow and combustion, the more shockwaves formed ahead of the combustor, which slowed and compressed the air before ignition.[41]

A scramjet is reminiscent of a ramjet. In a typical ramjet, the supersonic inflow of the engine is decelerated at the inlet to subsonic speeds and then reaccelerated through a nozzle to supersonic speeds to produce thrust. This deceleration, which is produced by a normal shock, creates a total pressure loss which limits the upper operating point of a ramjet engine.

For a scramjet, the kinetic energy of the freestream air entering the scramjet engine is largely comparable to the energy released by the reaction of the oxygen content of the air with a fuel (e.g. hydrogen). Thus the heat released from combustion at Mach 2.5 is around 10% of the total enthalpy of the working fluid. Depending on the fuel, the kinetic energy of the air and the potential combustion heat release will be equal at around Mach 8. Thus the design of a scramjet engine is as much about minimizing drag as maximizing thrust.

This high speed makes the control of the flow within the combustion chamber more difficult. Since the flow is supersonic, no downstream influence propagates within the freestream of the combustion chamber. Throttling of the entrance to the thrust nozzle is not a usable control technique. In effect, a block of gas entering the combustion chamber must mix with fuel and have sufficient time for initiation and reaction, all the while traveling supersonically through the combustion chamber, before the burned gas is expanded through the thrust nozzle. This places stringent requirements on the pressure and temperature of the flow, and requires that the fuel injection and mixing be extremely efficient. Usable dynamic pressures lie in the range 20 to 200 kilopascals (2.9 to 29.0 psi), where

where

To keep the combustion rate of the fuel constant, the pressure and temperature in the engine must also be constant. This is problematic because the airflow control systems that would facilitate this are not physically possible in a scramjet launch vehicle due to the large speed and altitude range involved, meaning that it must travel at an altitude specific to its speed. Because air density reduces at higher altitudes, a scramjet must climb at a specific rate as it accelerates to maintain a constant air pressure at the intake. This optimal climb/descent profile is called a "constant dynamic pressure path". It is thought that scramjets might be operable up to an altitude of 75 km.[42]

Fuel injection and management is also potentially complex. One possibility would be that the fuel be pressurized to 100 bar by a turbo pump, heated by the fuselage, sent through the turbine and accelerated to higher speeds than the air by a nozzle. The air and fuel stream are crossed in a comb-like structure, which generates a large interface. Turbulence due to the higher speed of the fuel leads to additional mixing. Complex fuels like kerosene need a long engine to complete combustion.

The minimum Mach number at which a scramjet can operate is limited by the fact that the compressed flow must be hot enough to burn the fuel, and have pressure high enough that the reaction be finished before the air moves out the back of the engine. Additionally, to be called a scramjet, the compressed flow must still be supersonic after combustion. Here two limits must be observed: First, since when a supersonic flow is compressed it slows down, the level of compression must be low enough (or the initial speed high enough) not to slow the gas below Mach 1. If the gas within a scramjet goes below Mach 1 the engine will "choke", transitioning to subsonic flow in the combustion chamber. This effect is well known amongst experimenters on scramjets since the waves caused by choking are easily observable. Additionally, the sudden increase in pressure and temperature in the engine can lead to an acceleration of the combustion, leading to the combustion chamber exploding.

Second, the heating of the gas by combustion causes the speed of sound in the gas to increase (and the Mach number to decrease) even though the gas is still travelling at the same speed. Forcing the speed of air flow in the combustion chamber under Mach 1 in this way is called "thermal choking". It is clear that a pure scramjet can operate at Mach numbers of 6–8,[43] but in the lower limit, it depends on the definition of a scramjet. There are engine designs where a ramjet transforms into a scramjet over the Mach 3–6 range, known as dual-mode scramjets.[44] In this range however, the engine is still receiving significant thrust from subsonic combustion of the ramjet type.

The high cost of flight testing and the unavailability of ground facilities have hindered scramjet development. A large amount of the experimental work on scramjets has been undertaken in cryogenic facilities, direct-connect tests, or burners, each of which simulates one aspect of the engine operation. Further, vitiated facilities (with the ability to control air impurities[45]), storage heated facilities, arc facilities and the various types of shock tunnels each have limitations which have prevented perfect simulation of scramjet operation. The HyShot flight test showed the relevance of the 1:1 simulation of conditions in the T4 and HEG shock tunnels, despite having cold models and a short test time. The NASA-CIAM tests provided similar verification for CIAM's C-16 V/K facility and the Hyper-X project is expected to provide similar verification for the Langley AHSTF,[46] CHSTF,[47] and 8 ft (2.4 m) HTT.

Computational fluid dynamics has only recently [when?] reached a position to make reasonable computations in solving scramjet operation problems. Boundary layer modeling, turbulent mixing, two-phase flow, flow separation, and real-gas aerothermodynamics continue to be problems on the cutting edge of CFD. Additionally, the modeling of kinetic-limited combustion with very fast-reacting species such as hydrogen makes severe demands on computing resources.[48] Reaction schemes are numerically stiff requiring reduced reaction schemes.[clarification needed]

Much of scramjet experimentation remains classified. Several groups, including the US Navy with the SCRAM engine between 1968 and 1974, and the Hyper-X program with the X-43A, have claimed successful demonstrations of scramjet technology. Since these results have not been published openly, they remain unverified and a final design method of scramjet engines still does not exist.

The final application of a scramjet engine is likely to be in conjunction with engines which can operate outside the scramjet's operating range.[citation needed] Dual-mode scramjets combine subsonic combustion with supersonic combustion for operation at lower speeds, and rocket-based combined cycle (RBCC) engines supplement a traditional rocket's propulsion with a scramjet, allowing for additional oxidizer to be added to the scramjet flow. RBCCs offer a possibility to extend a scramjet's operating range to higher speeds or lower intake dynamic pressures than would otherwise be possible.

Characteristics

[edit]Aircraft

[edit]- Does not have to carry oxygen

- No rotating parts makes it easier to manufacture than a turbojet

- Has a higher specific impulse (change in momentum per unit of propellant) than a rocket engine; could provide between 1000 and 4000 seconds, while a rocket typically provides around 450 seconds or less.[49]

- Higher speed could mean cheaper access to outer space in the future

- Difficult / expensive testing and development

- Very high initial propulsion requirements

Unlike a rocket that quickly passes mostly vertically through the atmosphere or a turbojet or ramjet that flies at much lower speeds, a hypersonic airbreathing vehicle optimally flies a "depressed trajectory", staying within the atmosphere at hypersonic speeds. Because scramjets have only mediocre thrust-to-weight ratios,[50] acceleration would be limited. Therefore, time in the atmosphere at supersonic speed would be considerable, possibly 15–30 minutes. Similar to a reentering space vehicle, heat insulation would be a formidable task, with protection required for a duration longer than that of a typical space capsule, although less than the Space Shuttle.

New materials offer good insulation at high temperature, but they often sacrifice themselves in the process. Therefore, studies often plan on "active cooling", where coolant circulating throughout the vehicle skin prevents it from disintegrating. Often the coolant is the fuel itself, in much the same way that modern rockets use their own fuel and oxidizer as coolant for their engines. All cooling systems add weight and complexity to a launch system. The cooling of scramjets in this way may result in greater efficiency, as heat is added to the fuel prior to entry into the engine, but results in increased complexity and weight which ultimately could outweigh any performance gains.

The performance of a launch system is complex and depends greatly on its weight. Normally craft are designed to maximise range (), orbital radius () or payload mass fraction () for a given engine and fuel. This results in tradeoffs between the efficiency of the engine (takeoff fuel weight) and the complexity of the engine (takeoff dry weight), which can be expressed by the following:

Where :

- is the empty mass fraction, and represents the weight of the superstructure, tankage and engine.

- is the fuel mass fraction, and represents the weight of fuel, oxidiser and any other materials which are consumed during the launch.

- is initial mass ratio, and is the inverse of the payload mass fraction. This represents how much payload the vehicle can deliver to a destination.

A scramjet increases the mass of the motor over a rocket, and decreases the mass of the fuel . It can be difficult to decide whether this will result in an increased (which would be an increased payload delivered to a destination for a constant vehicle takeoff weight). The logic behind efforts driving a scramjet is (for example) that the reduction in fuel decreases the total mass by 30%, while the increased engine weight adds 10% to the vehicle total mass. Unfortunately the uncertainty in the calculation of any mass or efficiency changes in a vehicle is so great that slightly different assumptions for engine efficiency or mass can provide equally good arguments for or against scramjet powered vehicles.

Additionally, the drag of the new configuration must be considered. The drag of the total configuration can be considered as the sum of the vehicle drag () and the engine installation drag (). The installation drag traditionally results from the pylons and the coupled flow due to the engine jet, and is a function of the throttle setting. Thus it is often written as:

Where:

- is the loss coefficient

- is the thrust of the engine

For an engine strongly integrated into the aerodynamic body, it may be more convenient to think of () as the difference in drag from a known base configuration.

The overall engine efficiency can be represented as a value between 0 and 1 (), in terms of the specific impulse of the engine:

Where:

- is the acceleration due to gravity at ground level

- is the vehicle speed

- is the specific impulse

- is fuel heat of reaction

Specific impulse is often used as the unit of efficiency for rockets, since in the case of the rocket, there is a direct relation between specific impulse, specific fuel consumption and exhaust velocity. This direct relation is not generally present for airbreathing engines, and so specific impulse is less used in the literature. Note that for an airbreathing engine, both and are a function of velocity.

The specific impulse of a rocket engine is independent of velocity, and common values are between 200 and 600 seconds (450 s for the space shuttle main engines). The specific impulse of a scramjet varies with velocity, reducing at higher speeds, starting at about 1200 s,[citation needed] although values in the literature vary.[citation needed]

For the simple case of a single stage vehicle, the fuel mass fraction can be expressed as:

Where this can be expressed for single stage transfer to orbit as:

or for level atmospheric flight from air launch (missile flight):

Where is the range, and the calculation can be expressed in the form of the Breguet range formula:

Where:

- is the lift coefficient

- is the drag coefficient

This extremely simple formulation, used for the purposes of discussion assumes:

- Single stage vehicle

- No aerodynamic lift for the transatmospheric lifter

However they are true generally for all engines.

A scramjet cannot produce efficient thrust unless boosted to high speed, around Mach 5, although depending on the design it could act as a ramjet at low speeds. A horizontal take-off aircraft would need conventional turbofan, turbojet, or rocket engines to take off, sufficiently large to move a heavy craft. Also needed would be fuel for those engines, plus all engine-associated mounting structure and control systems. Turbofan and turbojet engines are heavy and cannot easily exceed about Mach 2–3, so another propulsion method would be needed to reach scramjet operating speed. That could be ramjets or rockets. Those would also need their own separate fuel supply, structure, and systems. Many proposals instead call for a first stage of droppable solid rocket boosters, which greatly simplifies the design.

Unlike jet or rocket propulsion systems facilities which can be tested on the ground, testing scramjet designs uses extremely expensive hypersonic test chambers or expensive launch vehicles, both of which lead to high instrumentation costs. Tests using launched test vehicles very typically end with destruction of the test item and instrumentation.

Orbital vehicles

[edit]An advantage of a hypersonic airbreathing (typically scramjet) vehicle like the X-30 is avoiding or at least reducing the need for carrying oxidizer. For example, the Space Shuttle external tank held 616,432.2 kg of liquid oxygen (LOX) and 103,000 kg of liquid hydrogen (LH2) while having an empty weight of 30,000 kg. The orbiter gross weight was 109,000 kg with a maximum payload of about 25,000 kg and to get the assembly off the launch pad the shuttle used two very powerful solid rocket boosters with a weight of 590,000 kg each. If the oxygen could be eliminated, the vehicle could be lighter at liftoff and possibly carry more payload.

On the other hand, scramjets spend more time in the atmosphere and require more hydrogen fuel to deal with aerodynamic drag. Whereas liquid oxygen is quite a dense fluid (1141 kg/m3), liquid hydrogen has much lower density (70.85 kg/m3) and takes up more volume. This means that the vehicle using this fuel becomes much bigger and gives more drag.[51] Other fuels have more comparable density, such as RP-1 (810 kg/m3) JP-7 (density at 15 °C 779–806 kg/m3) and unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH) (793.00 kg/m3).

One issue is that scramjet engines are predicted to have exceptionally poor thrust-to-weight ratio of around 2, when installed in a launch vehicle.[52] A rocket has the advantage that its engines have very high thrust-weight ratios (~100:1), while the tank to hold the liquid oxygen approaches a volume ratio of ~100:1 also. Thus a rocket can achieve a very high mass fraction, which improves performance. By way of contrast the projected thrust/weight ratio of scramjet engines of about 2 mean a much larger percentage of the takeoff mass is engine (ignoring that this fraction increases anyway by a factor of about four due to the lack of onboard oxidiser). In addition the vehicle's lower thrust does not necessarily avoid the need for the expensive, bulky, and failure-prone high performance turbopumps found in conventional liquid-fuelled rocket engines, since most scramjet designs seem to be incapable of orbital speeds in airbreathing mode, and hence extra rocket engines are needed.[citation needed]

Scramjets might be able to accelerate from approximately Mach 5–7 to around somewhere between half of orbital speed and orbital speed (X-30 research suggested that Mach 17 might be the limit compared to an orbital speed of Mach 25, and other studies put the upper speed limit for a pure scramjet engine between Mach 10 and 25, depending on the assumptions made). Generally, another propulsion system (very typically, a rocket is proposed) is expected to be needed for the final acceleration into orbit. Since the delta-V is moderate and the payload fraction of scramjets high, lower performance rockets such as solids, hypergolics, or simple liquid fueled boosters might be acceptable.

Theoretical projections place the top speed of a scramjet between Mach 12 (14,000 km/h; 8,400 mph) and Mach 24 (25,000 km/h; 16,000 mph).[53] For comparison, the orbital speed at 200 kilometres (120 mi) low Earth orbit is 7.79 kilometres per second (28,000 km/h; 17,400 mph).[54]

The scramjet's heat-resistant underside potentially doubles as its reentry system if a single-stage-to-orbit vehicle using non-ablative, non-active cooling is visualised. If an ablative shielding is used on the engine it will probably not be usable after ascent to orbit. If active cooling is used with the fuel as coolant, the loss of all fuel during the burn to orbit will also mean the loss of all cooling for the thermal protection system.

Reducing the amount of fuel and oxidizer does not necessarily improve costs as rocket propellants are comparatively very cheap. Indeed, the unit cost of the vehicle can be expected to end up far higher, since aerospace hardware cost is about two orders of magnitude higher than liquid oxygen, fuel and tankage, and scramjet hardware seems to be much heavier than rockets for any given payload. Still, if scramjets enable reusable vehicles, this could theoretically be a cost benefit. Whether equipment subject to the extreme conditions of a scramjet can be reused sufficiently many times is unclear; all flown scramjet tests only survive for short periods and have never been designed to survive a flight to date. The eventual cost of such a vehicle is the subject of intense debate[by whom?] since even the best estimates disagree whether a scramjet vehicle would be advantageous. It is likely that a scramjet vehicle would need to lift more load than a rocket of equal takeoff weight to be equally as cost efficient (if the scramjet is a non-reusable vehicle).[citation needed]

Space launch vehicles may or may not benefit from having a scramjet stage. A scramjet stage of a launch vehicle theoretically provides a specific impulse of 1000 to 4000 s whereas a rocket provides less than 450 s while in the atmosphere.[52][55] A scramjet's specific impulse decreases rapidly with speed, however, and the vehicle would suffer from a relatively low lift to drag ratio.

The installed thrust to weight ratio of scramjets compares very unfavorably with the 50–100 of a typical rocket engine. This is compensated for in scramjets partly because the weight of the vehicle would be carried by aerodynamic lift rather than pure rocket power (giving reduced 'gravity losses'),[citation needed] but scramjets would take much longer to get to orbit due to lower thrust which greatly offsets the advantage. The takeoff weight of a scramjet vehicle is significantly reduced over that of a rocket, due to the lack of onboard oxidiser, but increased by the structural requirements of the larger and heavier engines.

Whether this vehicle could be reusable or not is still a subject of debate and research.

Proposed applications

[edit]An aircraft using this type of jet engine could dramatically reduce the time it takes to travel from one place to another, potentially putting any place on Earth within a 90-minute flight. However, there are questions about whether such a vehicle could carry enough fuel to make useful length trips. In addition, some countries ban or penalize airliners and other civil aircraft that create sonic booms. (For example, in the United States, FAA regulations prohibit supersonic flights over land, by civil aircraft.[56][57] [58])

Scramjet vehicle has been proposed for a single stage to tether vehicle, where a Mach 12 spinning orbital tether would pick up a payload from a vehicle at around 100 km and carry it to orbit.[59]

See also

[edit]- Avangard (hypersonic glide vehicle)

- Precooled jet engine

- Ram accelerator

- Shcramjet

- SABRE (rocket engine)

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Lorin Ramjet". www.enginehistory.org.

- ^ Analysis of Ignition Process in a Scramjet at Low and High Fueling Rates, Gareth Dunlap, Elias Fekadu, Ben Grove, Nick Gabsa, Kenneth Yu, Camilo Munoz, Jason Burr.

- ^ Urzay, Javier (2018). "Supersonic combustion in air-breathing propulsion systems for hypersonic flight". Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 50 (1): 593–627. Bibcode:2018AnRFM..50..593U. doi:10.1146/annurev-fluid-122316-045217.

- ^ Weber, Richard J.; Mackay, John S. (September 1958). "An Analysis of Ramjet Engines Using Supersonic Combustion". ntrs.nasa.gov. NASA Scientific and Technical Information. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ "Frederick S. Billig, Ph.D." The Clark School Innovation Hall of Fame. University of Maryland. Archived from the original on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ "Milestones in the history of scramjets". UQ News. University of Queensland. 27 July 2002. Archived from the original on 11 February 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ Roudakov, Alexander S.; Schickhmann, Y.; Semenov, Vyacheslav L.; Novelli, Ph.; Fourt, O. (1993). "Flight Testing an Axisymmetric Scramjet – Recent Russian Advances". 44th Congress of the International Astronautical Federation. Vol. 10. Graz, Austria: International Astronautical Federation.

- ^ Roudakov, Alexander S.; Semenov, Vyacheslav L.; Kopchenov, Valeriy I.; Hicks, John W. (1996). "Future Flight Test Plans of an Axisymmetric Hydrogen-Fueled Scramjet Engine on the Hypersonic Flying Laboratory" (PDF). 7th International Spaceplanes and Hypersonics Systems & Technology Conference November 18–22, 1996/Norfolk, Virginia. AIAA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Roudakov, Alexander S.; Semenov, Vyacheslav L.; Hicks, John W. (1998). "Recent Flight Test Results of the Joint CIAMNASA Mach 6.5 Scramjet Flight Program" (PDF). Central Institute of Aviation Motors, Moscow, Russia/NASA Dryden Flight Research Center Edwards, California, USA. NASA Center for AeroSpace Information (CASI). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Smart, Michael K.; Hass, Neal E.; Paull, Allan (2006). "Flight Data Analysis of the HyShot 2 Scramjet Flight Experiment". AIAA Journal. 44 (10): 2366–2375. Bibcode:2006AIAAJ..44.2366S. doi:10.2514/1.20661. ISSN 0001-1452.

- ^ Challoner, Jack (2 February 2009). 1001 Inventions That Changed the World. London: Cassell Illustrated. p. 932. ISBN 978-1-84403-611-0.

- ^ Harsha, Philip T.; Keel, Lowell C.; Castrogiovanni, Anthony; Sherrill, Robert T. (17 May 2005). "2005-3334: X-43A Vehicle Design and Manufacture". AIAA/CIRA 13th International Space Planes and Hypersonics Systems and Technologies Conference. Capua, Italy: AIAA. doi:10.2514/6.2005-3334. ISBN 978-1-62410-068-0.

- ^ McClinton, Charles (9 January 2006). "X-43: Scramjet Power Breaks the Hypersonic Barrier" (PDF). AIAA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "NASA – NASA's X-43A Scramjet Breaks Speed Record". www.nasa.gov. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ "Scramjet hits Mach 10 over Australia". New Scientist. Reed Business Information. 15 June 2007. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Ballard, Terry (2012), "Google Maps and Google Earth", Google This!, Elsevier, pp. 113–124, doi:10.1016/b978-1-84334-677-7.50009-7, ISBN 9781843346777, retrieved 2 June 2023

- ^ Cabell, Karen; Hass, Neal; Storch, Andrea; Gruber, Mark (11 April 2011). HIFiRE Direct-Connect Rig (HDCR) Phase I Scramjet Test Results from the NASA Langley Arc-Heated Scramjet Test Facility. 17th AIAA International Space Planes and Hypersonic Systems and Technologies Conference. NASA Technical Reports Server. hdl:2060/20110011173.

- ^ a b Dunning, Craig (24 May 2009). "Woomera hosts first HIFiRE hypersonic test flight". The Daily Telegraph. News Corp Australia. Archived from the original on 28 August 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ AAP (22 March 2010). "Scientists conduct second HIFiRE test". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Success for hypersonic outback flight". ABC News. ABC. 23 March 2010. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Longest Flight at Hypersonic Speed". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ^ Skillings, Jon (26 May 2010). "X-51A races to hypersonic record". CNET. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Hypersonic X-51A Scramjet Failure Perplexes Air Force". Space.com. Purch. 27 July 2011. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Cooper, Dani (16 November 2010). "Researchers put spark into scramjets". ABC Science. ABC. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Hypersonic jet Waverider fails Mach 6 test". BBC News. BBC. 15 August 2012. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ AP (6 May 2013). "Experimental hypersonic aircraft hits 4828 km/h". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Scramjet engines successfully tested: All you need to know about Isro's latest feat". Firstpost. 28 August 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ "Successful Flight Testing of ISRO's Scramjet Engine Technology Demonstrator – ISRO". www.isro.gov.in. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017.

- ^ "India successfully conducts flight test of unmanned scramjet demonstration aircraft". The Times of India. 12 June 2019.

- ^ "India test fires Hypersonic Technology Demonstrator Vehicle". Business Standard. 12 June 2019.

- ^ "DARPA'S Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC) Achieves Successful Flight". DARPA press release. DARPA. 27 September 2021.

- ^ "US tested hypersonic missile in mid-March but kept it quiet to avoid escalating tensions with Russia". CNN. 5 April 2022.

- ^ https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2022-04-05 [bare URL]

- ^ a b LaRC, Bob Allen. "NASA - How Scramjets Work". www.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2 December 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ Segal 2009, pp. 1.

- ^ Colaguori, Nancy; Kidder, Brian (26 May 2010). "Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne Scramjet Powers Historic First Flight of X-51A WaveRider" (Press release). West Palm Beach, Florida: Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Experimental Air Force aircraft goes hypersonic". Phys.org. Omicron Technology Limited. 3 May 2013. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Segal 2009, pp. 3–11.

- ^ a b Hill & Peterson 1992, pp. 21.

- ^ Segal 2009, pp. 4.

- ^ Analysis of Ignition Process in a Scramjet at Low and High Fueling Rates, Gareth Dunlap, Elias Fekadu, Ben Grove, Nick Gabsa, Kenneth Yu, Camilo Munoz, Jason Burr.

- ^ "Scramjets". Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Paull, A.; Stalker, R. J.; Mee, D. J. (1 January 1995). "Supersonic Combustion Ramjet Propulsion Experiments In a Shock Tunnel". Shock Tunnel Studies of Scramjet Phenomena 1994. University of Queensland. hdl:2060/19960001680.

- ^ Voland, R. T.; Auslender, A. H.; Smart, M. K.; Roudakov, A. S.; Semenov, V. L.; Kopchenov, V. (1999). CIAM/NASA Mach 6.5 Scramjet Flight and Ground Test. 9th International Space Planes and Hypersonic Systems and Technologies Conference. Norfolk, Virginia: AIAA. doi:10.2514/MHYTASP99. hdl:2060/20040087160.

- ^ "The Hy-V Program – Ground Testing". Research. University of Virginia. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Arc-Heated Scramjet Test Facility". NASA Langley Research Center. 17 November 2005. Archived from the original on 24 October 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- ^ "Combustion-Heated Scramjet Test Facility". NASA Langley Research Center. 17 November 2005. Archived from the original on 24 October 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Guan, Xingyi; Das, Akshaya; Stein, Christopher J.; Heidar-Zadeh, Farnaz; Bertels, Luke; Liu, Meili; Haghighatlari, Mojtaba; Li, Jie; Zhang, Oufan; Hao, Hongxia; Leven, Itai; Head-Gordon, Martin; Head-Gordon, Teresa (17 May 2022). "A benchmark dataset for Hydrogen Combustion". Scientific Data. 9 (1): 215. Bibcode:2022NatSD...9..215G. doi:10.1038/s41597-022-01330-5. ISSN 2052-4463. PMC 9114378. PMID 35581204.

- ^ "Space Launchers – Delta". www.braeunig.us.

- ^ Rathore, Mahesh M. (2010). "Jet and Rocket Propulsions". Thermal Engineering. New Delhi, India: Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 966. ISBN 978-0-07-068113-2. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

A scramjet has very poor thrust to weight ratio (~2).

- ^ Johns, Lionel S.; Shaw, Alan; Sharfman, Peter; Williamson, Ray A.; DalBello, Richard (1989). "The National Aero-Space Plane". Round Trip to Orbit: Human Spaceflight Alternatives. Washington, D.C.: Congress of the United States. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-4289-2233-4. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ a b Varvill, Richard; Bond, Alan (2003). "A Comparison of Propulsion Concepts for SSTO Reusable Launchers" (PDF). Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 56: 108–117. Bibcode:2003JBIS...56..108V. ISSN 0007-084X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Mateu, Marta Marimon (2013). "Study of an Air-Breathing Engine for Hypersonic Flight" (PDF). Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

Figure 9-10, Page 20

- ^ "Orbital Parameters – Low Earth Circular Orbits". Space Surveillance. Australian Space Academy. Archived from the original on 11 February 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ Kors, David L. (1990). Experimental investigation of a 2-D dual mode scramjet with hydrogenfuel at Mach 4–6. 2nd International Aerospace Planes Conference. Orlando, Florida: AIAA. doi:10.2514/MIAPC90.

- ^ "FAA Promulgates Strict New Sonic Boom Regulation". The Environmental Law Reporter. Environmental Law Institute. 1973. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Sec. 91.817 — Civil aircraft sonic boom". FAA Regulations. RisingUp Aviation. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Random Location". www.random.org. 2019.

- ^ Bogar, Thomas J.; Forward, Robert L.; Bangham, Michal E.; Lewis, Mark J. (9 November 1999). Hypersonic Airplane Space Tether Orbital Launch (HASTOL) System (PDF). NIAC Fellows Meeting. Atlanta, Georgia: NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aerospaceplane – 1961. Aerospace Projects Review, Volume 2, No 5.

- Aspects of the Aerospace Plane. Flight International, 2 January 1964, pages 36–37.

- Segal, Corin (2009). The Scramjet Engine: Processes and Characteristics. New York City: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83815-3. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Hill, Philip Graham; Peterson, Carl R. (1992). Mechanics and Thermodynamics of Propulsion (2 ed.). Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-201-14659-2. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Billig, Frederick S. (1993). SCRAM - A Supersonic Combustion Ramjet Missile. 29th Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit. Monterey, California: AIAA. doi:10.2514/MJPC93.

- Ingenito, Antonella; Bruno, Claudio (2010). "Physics and Regimes of Supersonic Combustion". AIAA Journal. 48 (3): 515–525. Bibcode:2010AIAAJ..48..515I. doi:10.2514/1.43652. hdl:11573/335488. ISSN 0001-1452.

- "On the trail of the Scramjet". The Lab. ABC. 17 October 2002. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- "Revolutionary jet engine tested". BBC News. BBC. 25 March 2006. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- "French Support Russian SCRAMJET Tests". Skunk Works Digest. 12 December 1992. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Schneider, David (2002). "A Burning Question". American Scientist. 90 (6): 1. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- "Hypersonic Scramjet Projectile Flys In Missile Test". SpaceDaily. Ronkonkoma, New York: Space Media Network. 4 September 2001. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- "National Hypersonics Plan". NASA Langley Research Center. 13 August 2003. Archived from the original on 7 August 2005.

- Smith, Yvette (2 October 2010). "X-43A". Missions. NASA. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- "HyShot". Centre for Hypersonics. University of Queensland. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Swinerd, Graham (2010). How spacecraft fly: spaceflight without formulae. Copernicus Books. ISBN 978-1-4419-2629-6.

External links

[edit]- Covault, Craig (17 May 2010). "Hypersonic X-51 Scramjet to Launch Test Flight in May". Space.com. Purch. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010.

- Guinan, Daniel P.; Drake, Alan; Andreadis, Dean; Beckel, Stephen A. (26 April 2005). "United States Patent: 6883330: Variable geometry inlet design for scram jet engine". USPTO. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Spencer, Henry. "Liquid Air Cycle Rocket Equation". Island One Society. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Leonard, David (16 August 2002). "Results Just In: HyShot Scramjet Test a Success". Space.com. Archived from the original on 26 September 2009.

- Wickham, Chris (28 November 2012). "British company claims biggest engine advance since the jet". Reuters. Thomson Reuters Corporation. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Satish, Kumar. "Scramjet Combustor Development" (PDF). Combustion Institute (Indian Section). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Wang, Brian (10 June 2011). "Aerojet has new Mach 7 plus reusable hypersonic vehicle plans". New Big Future. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

![{\displaystyle \Pi _{\text{f}}=1-\exp \left[-{\frac {\left({\frac {V_{\text{initial}}^{2}}{2}}-{\frac {V_{i}^{2}}{2}}\right)+\int {g}\,dr}{\eta _{0}h_{\text{PR}}\left(1-{\frac {D+D_{\text{e}}}{F}}\right)}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8135a72107646080c023a64c7c5bb92ab0a9413c)

![{\displaystyle \Pi _{\text{f}}=1-\exp \left[-{\frac {g_{0}r_{0}\left(1-{\frac {1}{2}}{\frac {r_{0}}{r}}\right)}{\eta _{0}h_{\text{PR}}\left(1-{\frac {D+D_{\text{e}}}{F}}\right)}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4ed5485bda4d142396f09fc125c4e38fdc141b4e)

![{\displaystyle \Pi _{\text{f}}=1-\exp \left[-{\frac {g_{0}R}{\eta _{0}h_{\text{PR}}\left(1-\phi _{\text{e}}\right){\frac {C_{\text{L}}}{C_{\text{D}}}}}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0a55f8c37d2a2e5a86065f105362c91be6f759ee)