Scattering

| Scattering |

|---|

|

In physics, scattering is a wide range of physical processes where moving particles or radiation of some form, such as light or sound, are forced to deviate from a straight trajectory by localized non-uniformities (including particles and radiation) in the medium through which they pass. In conventional use, this also includes deviation of reflected radiation from the angle predicted by the law of reflection. Reflections of radiation that undergo scattering are often called diffuse reflections and unscattered reflections are called specular (mirror-like) reflections. Originally, the term was confined to light scattering (going back at least as far as Isaac Newton in the 17th century[1]). As more "ray"-like phenomena were discovered, the idea of scattering was extended to them, so that William Herschel could refer to the scattering of "heat rays" (not then recognized as electromagnetic in nature) in 1800.[2] John Tyndall, a pioneer in light scattering research, noted the connection between light scattering and acoustic scattering in the 1870s.[3] Near the end of the 19th century, the scattering of cathode rays (electron beams)[4] and X-rays[5] was observed and discussed. With the discovery of subatomic particles (e.g. Ernest Rutherford in 1911[6]) and the development of quantum theory in the 20th century, the sense of the term became broader as it was recognized that the same mathematical frameworks used in light scattering could be applied to many other phenomena.

Scattering can refer to the consequences of particle-particle collisions between molecules, atoms, electrons, photons and other particles. Examples include: cosmic ray scattering in the Earth's upper atmosphere; particle collisions inside particle accelerators; electron scattering by gas atoms in fluorescent lamps; and neutron scattering inside nuclear reactors.[7]

The types of non-uniformities which can cause scattering, sometimes known as scatterers or scattering centers, are too numerous to list, but a small sample includes particles, bubbles, droplets, density fluctuations in fluids, crystallites in polycrystalline solids, defects in monocrystalline solids, surface roughness, cells in organisms, and textile fibers in clothing. The effects of such features on the path of almost any type of propagating wave or moving particle can be described in the framework of scattering theory.

Some areas where scattering and scattering theory are significant include radar sensing, medical ultrasound, semiconductor wafer inspection, polymerization process monitoring, acoustic tiling, free-space communications and computer-generated imagery.[8] Particle-particle scattering theory is important in areas such as particle physics, atomic, molecular, and optical physics, nuclear physics and astrophysics. In particle physics the quantum interaction and scattering of fundamental particles is described by the Scattering Matrix or S-Matrix, introduced and developed by John Archibald Wheeler and Werner Heisenberg.[9]

Scattering is quantified using many different concepts, including scattering cross section (σ), attenuation coefficients, the bidirectional scattering distribution function (BSDF), S-matrices, and mean free path.

Single and multiple scattering

[edit]

When radiation is only scattered by one localized scattering center, this is called single scattering. It is more common that scattering centers are grouped together; in such cases, radiation may scatter many times, in what is known as multiple scattering.[11] The main difference between the effects of single and multiple scattering is that single scattering can usually be treated as a random phenomenon, whereas multiple scattering, somewhat counterintuitively, can be modeled as a more deterministic process because the combined results of a large number of scattering events tend to average out. Multiple scattering can thus often be modeled well with diffusion theory.[12]

Because the location of a single scattering center is not usually well known relative to the path of the radiation, the outcome, which tends to depend strongly on the exact incoming trajectory, appears random to an observer. This type of scattering would be exemplified by an electron being fired at an atomic nucleus. In this case, the atom's exact position relative to the path of the electron is unknown and would be unmeasurable, so the exact trajectory of the electron after the collision cannot be predicted. Single scattering is therefore often described by probability distributions.

With multiple scattering, the randomness of the interaction tends to be averaged out by a large number of scattering events, so that the final path of the radiation appears to be a deterministic distribution of intensity. This is exemplified by a light beam passing through thick fog. Multiple scattering is highly analogous to diffusion, and the terms multiple scattering and diffusion are interchangeable in many contexts. Optical elements designed to produce multiple scattering are thus known as diffusers.[13] Coherent backscattering, an enhancement of backscattering that occurs when coherent radiation is multiply scattered by a random medium, is usually attributed to weak localization.

Not all single scattering is random, however. A well-controlled laser beam can be exactly positioned to scatter off a microscopic particle with a deterministic outcome, for instance. Such situations are encountered in radar scattering as well, where the targets tend to be macroscopic objects such as people or aircraft.

Similarly, multiple scattering can sometimes have somewhat random outcomes, particularly with coherent radiation. The random fluctuations in the multiply scattered intensity of coherent radiation are called speckles. Speckle also occurs if multiple parts of a coherent wave scatter from different centers. In certain rare circumstances, multiple scattering may only involve a small number of interactions such that the randomness is not completely averaged out. These systems are considered to be some of the most difficult to model accurately.

The description of scattering and the distinction between single and multiple scattering are tightly related to wave–particle duality.

Theory

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2023) |

Scattering theory is a framework for studying and understanding the scattering of waves and particles. Wave scattering corresponds to the collision and scattering of a wave with some material object, for instance (sunlight) scattered by rain drops to form a rainbow. Scattering also includes the interaction of billiard balls on a table, the Rutherford scattering (or angle change) of alpha particles by gold nuclei, the Bragg scattering (or diffraction) of electrons and X-rays by a cluster of atoms, and the inelastic scattering of a fission fragment as it traverses a thin foil. More precisely, scattering consists of the study of how solutions of partial differential equations, propagating freely "in the distant past", come together and interact with one another or with a boundary condition, and then propagate away "to the distant future".

The direct scattering problem is the problem of determining the distribution of scattered radiation/particle flux basing on the characteristics of the scatterer. The inverse scattering problem is the problem of determining the characteristics of an object (e.g., its shape, internal constitution) from measurement data of radiation or particles scattered from the object.

Attenuation due to scattering

[edit]

When the target is a set of many scattering centers whose relative position varies unpredictably, it is customary to think of a range equation whose arguments take different forms in different application areas. In the simplest case consider an interaction that removes particles from the "unscattered beam" at a uniform rate that is proportional to the incident number of particles per unit area per unit time (), i.e. that

where Q is an interaction coefficient and x is the distance traveled in the target.

The above ordinary first-order differential equation has solutions of the form:

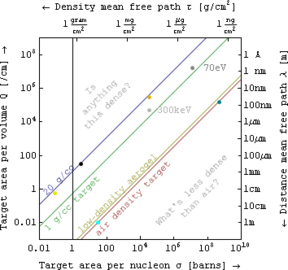

where Io is the initial flux, path length Δx ≡ x − xo, the second equality defines an interaction mean free path λ, the third uses the number of targets per unit volume η to define an area cross-section σ, and the last uses the target mass density ρ to define a density mean free path τ. Hence one converts between these quantities via Q = 1/λ = ησ = ρ/τ, as shown in the figure at left.

In electromagnetic absorption spectroscopy, for example, interaction coefficient (e.g. Q in cm−1) is variously called opacity, absorption coefficient, and attenuation coefficient. In nuclear physics, area cross-sections (e.g. σ in barns or units of 10−24 cm2), density mean free path (e.g. τ in grams/cm2), and its reciprocal the mass attenuation coefficient (e.g. in cm2/gram) or area per nucleon are all popular, while in electron microscopy the inelastic mean free path[14] (e.g. λ in nanometers) is often discussed[15] instead.

Elastic and inelastic scattering

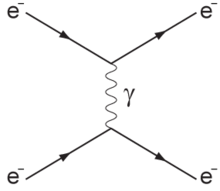

[edit]The term "elastic scattering" implies that the internal states of the scattering particles do not change, and hence they emerge unchanged from the scattering process. In inelastic scattering, by contrast, the particles' internal state is changed, which may amount to exciting some of the electrons of a scattering atom, or the complete annihilation of a scattering particle and the creation of entirely new particles.

The example of scattering in quantum chemistry is particularly instructive, as the theory is reasonably complex while still having a good foundation on which to build an intuitive understanding. When two atoms are scattered off one another, one can understand them as being the bound state solutions of some differential equation. Thus, for example, the hydrogen atom corresponds to a solution to the Schrödinger equation with a negative inverse-power (i.e., attractive Coulombic) central potential. The scattering of two hydrogen atoms will disturb the state of each atom, resulting in one or both becoming excited, or even ionized, representing an inelastic scattering process.

The term "deep inelastic scattering" refers to a special kind of scattering experiment in particle physics.

Mathematical framework

[edit]In mathematics, scattering theory deals with a more abstract formulation of the same set of concepts. For example, if a differential equation is known to have some simple, localized solutions, and the solutions are a function of a single parameter, that parameter can take the conceptual role of time. One then asks what might happen if two such solutions are set up far away from each other, in the "distant past", and are made to move towards each other, interact (under the constraint of the differential equation) and then move apart in the "future". The scattering matrix then pairs solutions in the "distant past" to those in the "distant future".

Solutions to differential equations are often posed on manifolds. Frequently, the means to the solution requires the study of the spectrum of an operator on the manifold. As a result, the solutions often have a spectrum that can be identified with a Hilbert space, and scattering is described by a certain map, the S matrix, on Hilbert spaces. Solutions with a discrete spectrum correspond to bound states in quantum mechanics, while a continuous spectrum is associated with scattering states. The study of inelastic scattering then asks how discrete and continuous spectra are mixed together.

An important, notable development is the inverse scattering transform, central to the solution of many exactly solvable models.

Theoretical physics

[edit]

In mathematical physics, scattering theory is a framework for studying and understanding the interaction or scattering of solutions to partial differential equations. In acoustics, the differential equation is the wave equation, and scattering studies how its solutions, the sound waves, scatter from solid objects or propagate through non-uniform media (such as sound waves, in sea water, coming from a submarine). In the case of classical electrodynamics, the differential equation is again the wave equation, and the scattering of light or radio waves is studied. In particle physics, the equations are those of Quantum electrodynamics, Quantum chromodynamics and the Standard Model, the solutions of which correspond to fundamental particles.

In regular quantum mechanics, which includes quantum chemistry, the relevant equation is the Schrödinger equation, although equivalent formulations, such as the Lippmann-Schwinger equation and the Faddeev equations, are also largely used. The solutions of interest describe the long-term motion of free atoms, molecules, photons, electrons, and protons. The scenario is that several particles come together from an infinite distance away. These reagents then collide, optionally reacting, getting destroyed or creating new particles. The products and unused reagents then fly away to infinity again. (The atoms and molecules are effectively particles for our purposes. Also, under everyday circumstances, only photons are being created and destroyed.) The solutions reveal which directions the products are most likely to fly off to and how quickly. They also reveal the probability of various reactions, creations, and decays occurring. There are two predominant techniques of finding solutions to scattering problems: partial wave analysis, and the Born approximation.

Electromagnetics

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2020) |

Electromagnetic waves are one of the best known and most commonly encountered forms of radiation that undergo scattering.[16] Scattering of light and radio waves (especially in radar) is particularly important. Several different aspects of electromagnetic scattering are distinct enough to have conventional names. Major forms of elastic light scattering (involving negligible energy transfer) are Rayleigh scattering and Mie scattering. Inelastic scattering includes Brillouin scattering, Raman scattering, inelastic X-ray scattering and Compton scattering.

Light scattering is one of the two major physical processes that contribute to the visible appearance of most objects, the other being absorption. Surfaces described as white owe their appearance to multiple scattering of light by internal or surface inhomogeneities in the object, for example by the boundaries of transparent microscopic crystals that make up a stone or by the microscopic fibers in a sheet of paper. More generally, the gloss (or lustre or sheen) of the surface is determined by scattering. Highly scattering surfaces are described as being dull or having a matte finish, while the absence of surface scattering leads to a glossy appearance, as with polished metal or stone.

Spectral absorption, the selective absorption of certain colors, determines the color of most objects with some modification by elastic scattering. The apparent blue color of veins in skin is a common example where both spectral absorption and scattering play important and complex roles in the coloration. Light scattering can also create color without absorption, often shades of blue, as with the sky (Rayleigh scattering), the human blue iris, and the feathers of some birds (Prum et al. 1998). However, resonant light scattering in nanoparticles can produce many different highly saturated and vibrant hues, especially when surface plasmon resonance is involved (Roqué et al. 2006).[17][18]

Models of light scattering can be divided into three domains based on a dimensionless size parameter, α which is defined as: where πDp is the circumference of a particle and λ is the wavelength of incident radiation in the medium. Based on the value of α, these domains are:

- α ≪ 1: Rayleigh scattering (small particle compared to wavelength of light);

- α ≈ 1: Mie scattering (particle about the same size as wavelength of light, valid only for spheres);

- α ≫ 1: geometric scattering (particle much larger than wavelength of light).

Rayleigh scattering is a process in which electromagnetic radiation (including light) is scattered by a small spherical volume of variant refractive indexes, such as a particle, bubble, droplet, or even a density fluctuation. This effect was first modeled successfully by Lord Rayleigh, from whom it gets its name. In order for Rayleigh's model to apply, the sphere must be much smaller in diameter than the wavelength (λ) of the scattered wave; typically the upper limit is taken to be about 1/10 the wavelength. In this size regime, the exact shape of the scattering center is usually not very significant and can often be treated as a sphere of equivalent volume. The inherent scattering that radiation undergoes passing through a pure gas is due to microscopic density fluctuations as the gas molecules move around, which are normally small enough in scale for Rayleigh's model to apply. This scattering mechanism is the primary cause of the blue color of the Earth's sky on a clear day, as the shorter blue wavelengths of sunlight passing overhead are more strongly scattered than the longer red wavelengths according to Rayleigh's famous 1/λ4 relation. Along with absorption, such scattering is a major cause of the attenuation of radiation by the atmosphere.[19] The degree of scattering varies as a function of the ratio of the particle diameter to the wavelength of the radiation, along with many other factors including polarization, angle, and coherence.[20]

For larger diameters, the problem of electromagnetic scattering by spheres was first solved by Gustav Mie, and scattering by spheres larger than the Rayleigh range is therefore usually known as Mie scattering. In the Mie regime, the shape of the scattering center becomes much more significant and the theory only applies well to spheres and, with some modification, spheroids and ellipsoids. Closed-form solutions for scattering by certain other simple shapes exist, but no general closed-form solution is known for arbitrary shapes.

Both Mie and Rayleigh scattering are considered elastic scattering processes, in which the energy (and thus wavelength and frequency) of the light is not substantially changed. However, electromagnetic radiation scattered by moving scattering centers does undergo a Doppler shift, which can be detected and used to measure the velocity of the scattering center/s in forms of techniques such as lidar and radar. This shift involves a slight change in energy.

At values of the ratio of particle diameter to wavelength more than about 10, the laws of geometric optics are mostly sufficient to describe the interaction of light with the particle. Mie theory can still be used for these larger spheres, but the solution often becomes numerically unwieldy.

For modeling of scattering in cases where the Rayleigh and Mie models do not apply such as larger, irregularly shaped particles, there are many numerical methods that can be used. The most common are finite-element methods which solve Maxwell's equations to find the distribution of the scattered electromagnetic field. Sophisticated software packages exist which allow the user to specify the refractive index or indices of the scattering feature in space, creating a 2- or sometimes 3-dimensional model of the structure. For relatively large and complex structures, these models usually require substantial execution times on a computer.

Electrophoresis involves the migration of macromolecules under the influence of an electric field.[21] Electrophoretic light scattering involves passing an electric field through a liquid which makes particles move. The bigger the charge is on the particles, the faster they are able to move.[22]

See also

[edit]- Attenuation#Light scattering

- Backscattering

- Bragg diffraction

- Brillouin scattering

- Characteristic mode analysis

- Compton scattering

- Coulomb scattering

- Deep scattering layer

- Diffuse sky radiation

- Doppler effect

- Dynamic Light Scattering

- Electron diffraction

- Electron scattering

- Electrophoretic light scattering

- Extinction

- Haag–Ruelle scattering theory

- Kikuchi line

- Light scattering by particles

- Linewidth

- Mie scattering

- Mie theory

- Molecular scattering

- Mott scattering

- Neutron scattering

- Phase space measurement with forward modeling

- Photon diffusion

- Powder diffraction

- Raman scattering

- Rayleigh scattering

- Resonances in scattering from potentials

- Rutherford scattering

- Small-angle scattering

- Scattering amplitude

- Scattering from rough surfaces

- Scintillation (physics)

- S-Matrix

- Tyndall effect

- Thomson scattering

- Wolf effect

- X-ray crystallography

References

[edit]- ^ Newton, Isaac (1665). "A letter of Mr. Isaac Newton Containing his New Theory About Light and Colours". Philosophical Transactions. 6. Royal Society of London: 3087.

- ^ Herschel, William (1800). "Experiments on the Solar, and on the Terrestrial Rays that Occasion Heat". Philosophical Transactions. XC. Royal Society of London: 770.

- ^ Tyndall, John (1874). "On the Atmosphere as a Vehicle of Sound". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 164: 221. Bibcode:1874RSPT..164..183T. JSTOR 109101.

- ^ Merritt, Ernest (5 Oct 1898). "The Magnetic Deflection of Diffusely Reflected Cathode Rays". Electrical Review. 33 (14): 217.

- ^ "Recent Work with Röntgen Rays". Nature. 53 (1383): 613–616. 30 Apr 1896. Bibcode:1896Natur..53..613.. doi:10.1038/053613a0. S2CID 4023635.

- ^ Rutherford, E. (1911). "The Scattering of α and β rays by Matter and the Structure of the Atom". Philosophical Magazine. 6: 21.

- ^ Seinfeld, John H.; Pandis, Spyros N. (2006). Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics - From Air Pollution to Climate Change (2nd Ed.). John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-82857-2

- ^ Colton, David; Rainer Kress (1998). Inverse Acoustic and Electromagnetic Scattering Theory. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-62838-5.

- ^ Nachtmann, Otto (1990). Elementary Particle Physics: Concepts and Phenomena. Springer-Verlag. pp. 80–93. ISBN 3-540-50496-6.

- ^ "Zodiacal Glow Lightens Paranal Sky". ESO Picture of the Week. European Southern Observatory. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^ Gonis, Antonios; William H. Butler (1999). Multiple Scattering in Solids. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-98853-5.

- ^ Gonis, Antonios; William H. Butler (1999). Multiple Scattering in Solids. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-98853-5.

- ^ Stover, John C. (1995). Optical Scattering: Measurement and Analysis. SPIE Optical Engineering Press. ISBN 978-0-8194-1934-7.

- ^ R. F. Egerton (1996) Electron energy-loss spectroscopy in the electron microscope (Second Edition, Plenum Press, NY) ISBN 0-306-45223-5

- ^ Ludwig Reimer (1997) Transmission electron microscopy: Physics of image formation and microanalysis (Fourth Edition, Springer, Berlin) ISBN 3-540-62568-2

- ^ Colton, David; Rainer Kress (1998). Inverse Acoustic and Electromagnetic Scattering Theory. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-62838-5.

- ^ Bohren, Craig F.; Donald R. Huffman (1983). Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-29340-8.

- ^ Roqué, Josep; J. Molera; P. Sciau; E. Pantos; M. Vendrell-Saz (2006). "Copper and silver nanocrystals in lustre lead glazes: development and optical properties". Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 26 (16): 3813–3824. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2005.12.024.

- ^ Seinfeld, John H.; Pandis, Spyros N. (2006). Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics - From Air Pollution to Climate Change (2nd Ed.). John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-82857-2

- ^ Prum, Richard O.; Rodolfo H. Torres; Scott Williamson; Jan Dyck (1998). "Coherent light scattering by blue feather barbs". Nature. 396 (6706): 28–29. Bibcode:1998Natur.396...28P. doi:10.1038/23838. S2CID 4393904.

- ^ "Understanding Electrophoretic Light Scattering". Wyatt Technology.

- ^ "Light Scattering". Malvern Panalytical.

External links

[edit]- Research group on light scattering and diffusion in complex systems

- Multiple light scattering from a photonic science point of view

- Neutron Scattering Web

- Neutron and X-Ray Scattering

- World directory of neutron scattering instruments

- Scattering and diffraction

- Optics Classification and Indexing Scheme (OCIS), Optical Society of America, 1997

- Lectures of the European school on theoretical methods for electron and positron induced chemistry, Prague, Feb. 2005

- E. Koelink, Lectures on scattering theory, Delft the Netherlands 2006