Constantijn Huygens Jr.

Constantijn Huygens Jr. | |

|---|---|

Constantijn Huygens Jr., self portrait (1685) | |

| Born | 10 March 1628 |

| Died | October 1697 The Hague |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Alma mater | University of Leiden |

| Known for | Aerial telescope, diaries |

| Spouse | Susanna Rijckaert |

| Children | 2 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy Optics |

Constantijn Huygens Jr., Lord of Zuilichem (10 March 1628 – October 1697), was a Dutch statesman and poet, mostly known for his work on scientific instruments (sometimes together with his younger brother Christiaan Huygens). But, he was also a chronicler of his times, revealing the importance of gossip.[1][2][3] Additionally, he was an amateur draughtsman of landscapes.

Biography

[edit]Constantijn Huygens was the eldest son of Sir Constantijn Huygens, a poet and statesman, and Suzanna van Baerle. He was taught at home by his father and private tutors. In 1637 his mother died.[4] Around 1640 the family was depicted by Adriaen Hanneman. Along with his younger brother Christiaan Huygens, he began his studies at Leiden university in 1645, studying law.[5] He studied the works of classical authors on history, philosophy, and science, including mathematics from Frans van Schooten.

In 1649–1650 Huygens accompanied Adriaen Pauw to England [6] and toured through Belgium, France, Switzerland and Italy. In 1655 he moved to Paris. He joined the circle around Honoré Fabri. In the Hague he also was visiting the salon, organized by the wife of François Caron. In 1668 he married Susanna Rijckaert (1642–1712), a rich woman from Amsterdam.[7][8] In April 1676, during his stay in Zemst he was visited by David Teniers the Younger. In 1680 Huygens visited Celle and moved out of his father's house. It is not sure if it had to do with Abraham de Wicquefort or Sophia Dorothea of Celle. To stop the gossip his father wrote a poem: Cluijs-werck.

When William III of England became stadtholder in 1672, Huygens had been appointed as his secretary.[9] Huygens participated in the campaigns against the French, in the Glorious Revolution, but did not attend the crowning. He described the Battle of the Boyne. During the Nine Years' War, Constantijn left for the Southern Netherlands each spring, returning to London each autumn.[10] Huygens became friends with or wrote about the Groom of the Stole William Bentinck, Arnold van Keppel, 1st Earl of Albemarle, William Nassau de Zuylestein, Everhard van Weede Dijkvelt, Coenraad van Beuningen and Adrian Beverland. When William Blathwayt surpassed him as secretary, Huygens was frustrated and in 1695 he received permission to return to the Dutch Republic.He formally remained William's private secretary, however. As such he was succeeded by Abel Tassin d'Alonne after Huygen's death.[11]

Huygens died in October 1697 and was buried on 2 November 1697. With Susanna, he had one son, who died in 1704. He had one daughter from an earlier affair.

Telescopes and optics

[edit]

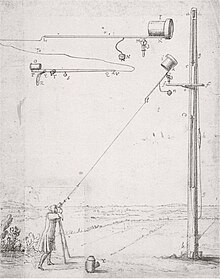

Around 1650 when Christiaan Huygens became interested in microscopes and telescopes, Constantijn helped him with the construction of the lenses. In 1655 Christiaan discovered Titan, a moon orbiting Saturn.[12] Between 1683 and 1687 Constantijn and his brother continued to make larger and longer focal length telescope objectives culminating in the very large tubeless aerial telescopes. He presented a 7.5 inch (190mm) diameter 123 ft (37.5 m) focal length aerial telescope objective to the Royal Society in 1690[13] that still bears his signature.[14]

Diary

[edit]From 1673 to 1696, Huygens kept a private diary (now at the Koninklijke Bibliotheek). Between 1649 and 1697 Huygens filled 1,599 pages.[15][16] In this diary he recorded all aspects of early-modern court life in Holland and England.[17] The book includes chapters on such subjects as the changing perception of time, book collecting, Huygens's role as connoisseur of art, belief in magic and witchcraft, and gossip and sexuality at the court of William and Mary. It provides an insight on the history of human sexuality.[18] Huygens is comparable to his English contemporary, Samuel Pepys, but with an important difference: whereas Pepys mainly describes his own sexual habits, Huygens almost exclusively describes those of others.[15]

Drawings and paintings

[edit]

Like his ancestor Joris Hoefnagel, Constantijn practised his skill in drawing. With the death of his father in 1687, he inherited the Heerlijkheid and the castle of Zuilichem (nearby Zaltbommel), by which he became known as Lord of Zuilichem (in Dutch: Heer van Zuilichem).[19][20] Huygens Jr. made some drawings and paintings, depicting this castle in the period between 1650 till 1660.[21] They can be seen at the museum Maarten van Rossum at Zaltbommel.

Constantijn was an art connoisseur and advised setting up the gallery in Kensington Palace. He is connected to the Codex Windsor manuscript by Leonardo da Vinci and the Codex Huygens, copied after Leonardo's journals.[22][23] The latter Constantijn received in 1690; he mended and mounted it, believing it to be a Leonardo original, though it is more likely by either Bernardino Campi or Carlo Urbino.[24][25] According to Huygens, Romeyn de Hooghe illustrated La puttana errante, an erotic book by Pietro Aretino.[26]

References

[edit]- ^ Dekker, Rudolf M. (7 June 2013). Family, Culture and Society in the Diary of Constantijn Huygens Jr. ISBN 978-9004250956.

- ^ Le "Journaal" de C. Huygens, le jeune : extraits réunis et commentés / par Jean Gessler. La Haye : Nijhoff. 1933

- ^ Register op de Journalen van Constantijn Huygens Jr. Historisch genootschap, Utrecht. Werken.3. Serie, no. 22. Müller. 1906.

- ^ "Essential Vermeer". Essential Vermeer. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ ".physics.ubc.ca - LIFE of CHRISTIAAN HUYGHENS: Brief Notes, page 1" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-19. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ "Adriaan Pauw jr. (1622–1697) | Librariana". Ilibrariana.wordpress.com. 2012-02-29. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ "Susanna Ryckaert". Burckhardt.ic.uva.nl. Archived from the original on 2013-09-10. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ "DBNL". DBNL. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ Family, Culture and Society in the Diary of Constantijn Huygens Jr, Secretary to Stadholder-King William of Orange by Rudolf Dekker [1]

- ^ "British Society for the History of Mathematics". Dcs.warwick.ac.uk. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ Leeuw, K. de (1999). "The Black Chamber in the Dutch Republic during the War of the Spanish Succession and it Aftermath, 1707-1715" (PDF). The Historical Journal. 42 (1): 66, note 84. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- ^ Museumboerhaave.nl Archived July 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Paul Schlyter, Largest optical telescopes of the world". Stjarnhimlen.se. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ In 1725 the Royal Society also acquired two very long focal length aerial telescope objectives, both made by Constantijn.

- ^ a b Dekker, R.M. (Rudolf) (1999-11-01). "RePub, Erasmus University Repository: Sexuality, Elites, and Court Life in the Late Seventeenth Century: The Diaries of Constantijn Huygens Jr". Eighteenth-Century Life. 23 (3). Repub.eur.nl: 94–109. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ His journals, covering period 1673, 1675-1678, 1688-1696, were published in six volumes by the Historisch Genootschap te Utrecht, 1876-1915.

- ^ "Project: Court culture, time consciousness and the development of autobiographical writing in the seventeenth century. An analysis of the diary of Constantijn Huygens Jr. (1628-1697) in a social and cultural context". Onderzoekinformatie.nl. Archived from the original on 2011-06-09. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ Smith, Pamela H.; Schmidt, Benjamin (2008). Making Knowledge in Early Modern Europe: Practices, Objects, and Texts, 1400 - 1800. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-226-76329-3.

- ^ http://www.nationalgallery.ie/en/Conservation/Featured_Projects/Battle_Of_Boyne/Project_Blog/Blog13_30Sept.aspx Archived 2017-02-06 at the Wayback Machine The Lord of Zuilichem] - website of the National Gallery of Ireland

- ^ Constantijn Huygens: Lord of Zuilichem - website of Essential Vermeer

- ^ HUYGENS Jr. - REDAKTIE, MET HUYGENS OP REIS Tekeningen en dagboeknotities van Constantijn Huygens jr. (1628–1697), secretaris van stadhouder-koning Willem III. Dutch text. Ant., 1983.

- ^ Henry Schuman (Ed.) Leonardo on the human body, p. 34. Courier Dover Publications, Mineola N.Y. 1983, ISBN 978-0-486-24483-9

- ^ Erwin Panofsky, The Codex Huygens and Leonardo da Vinci's art theory00, the Pierpont Morgan Library codex M.A. 1139, London: The Warburg Institute, 1940.

- ^ Bean, Jacob; Stampfle, Felice (1965). Drawings from New York Collections I: The Italian Renaissance. Greenwich, CT: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 81–82.

- ^ "Leonardo da Vinci and the Codex Huygens". The Morgan Library & Museum. October 22, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ "Rudolf Dekker and Judy Marcure - Sexuality, Elites, and Court Life in the Late Seventeenth Century: The Diaries of Constantijn Huygens Jr. - Eighteenth-Century Life 23:3" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-03-08.

External links

[edit]- (in Dutch) DBNL

- Rudolf M. Dekker on Constantijn Huygens Jr