Co-orbital configuration

In astronomy, a co-orbital configuration is a configuration of two or more astronomical objects (such as asteroids, moons, or planets) orbiting at the same, or very similar, distance from their primary; i.e., they are in a 1:1 mean-motion resonance. (or 1:-1 if orbiting in opposite directions).[1]

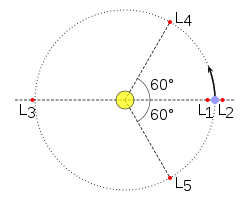

There are several classes of co-orbital objects, depending on their point of libration. The most common and best-known class is the trojan, which librates around one of the two stable Lagrangian points (Trojan points), L4 and L5, 60° ahead of and behind the larger body respectively. Another class is the horseshoe orbit, in which objects librate around 180° from the larger body. Objects librating around 0° are called quasi-satellites.[2]

An exchange orbit occurs when two co-orbital objects are of similar masses and thus exert a non-negligible influence on each other. The objects can exchange semi-major axes or eccentricities when they approach each other.

Parameters

[edit]Orbital parameters that are used to describe the relation of co-orbital objects are the longitude of the periapsis difference and the mean longitude difference. The longitude of the periapsis is the sum of the mean longitude and the mean anomaly and the mean longitude is the sum of the longitude of the ascending node and the argument of periapsis .

Trojans

[edit]

Trojan objects orbit 60° ahead of (L4) or behind (L5) a more massive object, both in orbit around an even more massive central object. The best known examples are the large population of asteroids that orbit ahead of or behind Jupiter around the Sun. Trojan objects do not orbit exactly at one of either Lagrangian points, but do remain relatively close to it, appearing to slowly orbit it. In technical terms, they librate around = (±60°, ±60°). The point around which they librate is the same, irrespective of their mass or orbital eccentricity.[2]

Trojan minor planets

[edit]There are several thousand known trojan minor planets orbiting the Sun. Most of these orbit near Jupiter's Lagrangian points, the traditional Jupiter trojans. As of 2015[update], there are also 13 Neptune trojans, 7 Mars trojans, 2 Uranus trojans ((687170) 2011 QF99 and (636872) 2014 YX49), and 2 Earth trojans (2010 TK7 and (614689) 2020 XL5 ) that are known to exist. No Saturnian trojans have been observed until the discovery of 2019 UO14.

Trojan moons

[edit]The Saturnian system contains two sets of trojan moons. Both Tethys and Dione have two trojan moons each, Telesto and Calypso in Tethys's L4 and L5 respectively, and Helene and Polydeuces in Dione's L4 and L5 respectively.

Polydeuces is noticeable for its wide libration: it wanders as far as ±30° from its Lagrangian point and ±2% from its mean orbital radius, along a tadpole orbit in 790 days (288 times its orbital period around Saturn, the same as Dione's).

Trojan planets

[edit]A pair of co-orbital exoplanets was proposed to be orbiting the star Kepler-223, but this was later retracted.[3]

The possibility of a trojan planet to Kepler-91b was studied but the conclusion was that the transit-signal was a false-positive.[4]

In April 2023, a group of amateur astronomers reported two new exoplanet candidates co-orbiting , in a horseshoe exchange orbit, close to the star GJ 3470 (this star has been known to have a confirmed planet GJ 3470 b). However, the mentioned study is only in preprint form on arXiv, and it has not yet been peer reviewed and published in a reputable scientific journal.[5][6]

In July 2023, the possible detection of a cloud of debris co-orbital with the proto-planet PDS 70 b was announced. This debris cloud could be evidence of a Trojan planetary-mass body or one in the process of forming.[7][8]

One possibility for the habitable zone is a trojan planet of a giant planet close to its star.[9]

The reason why no trojan planets have been definitively detected could be that tides destabilize their orbits.[10]

Formation of the Earth–Moon system

[edit]According to the giant impact hypothesis, the Moon formed after a collision between two co-orbital objects: Theia, thought to have had about 10% of the mass of Earth (about as massive as Mars), and the proto-Earth. Their orbits were perturbed by other planets, bringing Theia out of its trojan position and causing the collision.

Horseshoe orbits

[edit]

Saturn · Janus · Epimetheus

Objects in a horseshoe orbit librate around 180° from the primary. Their orbits encompass both equilateral Lagrangian points, i.e. L4 and L5.[2]

Co-orbital moons

[edit]The Saturnian moons Janus and Epimetheus share their orbits, the difference in semi-major axes being less than either's mean diameter. This means the moon with the smaller semi-major axis slowly catches up with the other. As it does this, the moons gravitationally tug at each other, increasing the semi-major axis of the moon that has caught up and decreasing that of the other. This reverses their relative positions proportionally to their masses and causes this process to begin anew with the moons' roles reversed. In other words, they effectively swap orbits, ultimately oscillating both about their mass-weighted mean orbit.

Earth co-orbital asteroids

[edit]A small number of asteroids have been found which are co-orbital with Earth. The first of these to be discovered, asteroid 3753 Cruithne, orbits the Sun with a period slightly less than one Earth year, resulting in an orbit that (from the point of view of Earth) appears as a bean-shaped orbit centered on a position ahead of the position of Earth. This orbit slowly moves further ahead of Earth's orbital position. When Cruithne's orbit moves to a position where it trails Earth's position, rather than leading it, the gravitational effect of Earth increases the orbital period, and hence the orbit then begins to lag, returning to the original location. The full cycle from leading to trailing Earth takes 770 years, leading to a horseshoe-shaped movement with respect to Earth.[11]

More resonant near-Earth objects (NEOs) have since been discovered. These include 54509 YORP, (85770) 1998 UP1, 2002 AA29, (419624) 2010 SO16, 2009 BD, and 2015 SO2 which exist in resonant orbits similar to Cruithne's. 2010 TK7 and (614689) 2020 XL5 are the only two identified Earth trojans.

Hungaria asteroids were found to be one of the possible sources for co-orbital objects of the Earth with a lifetime up to ~58 kyrs.[12]

Quasi-satellite

[edit]Quasi-satellites are co-orbital objects that librate around 0° from the primary. Low-eccentricity quasi-satellite orbits are highly unstable, but for moderate to high eccentricities such orbits can be stable.[2] From a co-rotating perspective the quasi-satellite appears to orbit the primary like a retrograde satellite, although at distances so large that it is not gravitationally bound to it.[2] Two examples of quasi-satellites of the Earth are 2014 OL339[13] and 469219 Kamoʻoalewa.[14][15]

Exchange orbits

[edit]In addition to swapping semi-major axes like Saturn's moons Epimetheus and Janus, another possibility is to share the same axis, but swap eccentricities instead.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Morais, M.H.M.; F. Namouni (2013). "Asteroids in retrograde resonance with Jupiter and Saturn". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters. 436: L30–L34. arXiv:1308.0216. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.436L..30M. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slt106.

- ^ a b c d e Dynamics of two planets in co-orbital motion

- ^ "Two planets found sharing one orbit". New Scientist. 24 February 2011.

- ^ Placek, Ben; Knuth, Kevin H.; Angerhausen, Daniel; Jenkins, Jon M. (2015). "Characterization of Kepler-91B and the Investigation of a Potential Trojan Companion Using Exonest". The Astrophysical Journal. 814 (2): 147. arXiv:1511.01068. Bibcode:2015ApJ...814..147P. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/814/2/147. S2CID 118366565.

- ^ "The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia — GJ 3470 d". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 2023-04-28.

- ^ "The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia — GJ 3470 e". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 2023-04-28.

- ^ Balsalobre-Ruza, O.; de Gregorio-Monsalvo, I.; et al. (July 2023). "Tentative co-orbital submillimeter emission within the Lagrangian region L5 of the protoplanet PDS 70 b". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 675: A172. arXiv:2307.12811. Bibcode:2023A&A...675A.172B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202346493. S2CID 259684169.

- ^ "Does this exoplanet have a sibling sharing the same orbit?". ESO. 19 July 2023. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ Dvorak, R.; Pilat-Lohinger, E.; Schwarz, R.; Freistetter, F. (2004). "Extrasolar Trojan planets close to habitable zones". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 426 (2): L37–L40. arXiv:astro-ph/0408079. Bibcode:2004A&A...426L..37D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200400075. S2CID 15637771.

- ^ Dobrovolskis, Anthony R.; Lissauer, Jack J. (2022). "Do tides destabilize Trojan exoplanets?". Icarus. 385: 115087. arXiv:2206.07097. Bibcode:2022Icar..38515087D. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2022.115087. S2CID 248979920.

- ^ Christou, A. A.; Asher, D. J. (2011). "A long-lived horseshoe companion to the Earth". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 414 (4): 2965. arXiv:1104.0036. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.414.2965C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18595.x. S2CID 13832179.

- ^ Galiazzo, M. A.; Schwarz, R. (2014). "The Hungaria region as a possible source of Trojans and satellites in the inner Solar system". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 445 (4): 3999. arXiv:1612.00275. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.445.3999G. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2016.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (2014). "Asteroid 2014 OL339: yet another Earth quasi-satellite". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 445 (3): 2985–2994. arXiv:1409.5588. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.445.2961D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu1978.

- ^ Agle, DC; Brown, Dwayne; Cantillo, Laurie (15 June 2016). "Small Asteroid Is Earth's Constant Companion". NASA. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (2016). "Asteroid (469219) 2016 HO3, the smallest and closest Earth quasi-satellite". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 462 (4): 3441–3456. arXiv:1608.01518. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.462.3441D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw1972.

- ^ Funk, B. (2010). "Exchange orbits: a possible application to extrasolar planetary systems?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 410 (1): 455–460. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.410..455F. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17453.x.

- Eric B. Ford and Matthew J. Holman (2007). "Using Transit Timing Observations to Search for Trojans of Transiting Extrasolar Planets". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 664 (1): L51–L54. arXiv:0705.0356. Bibcode:2007ApJ...664L..51F. doi:10.1086/520579. S2CID 14285948.

External links

[edit]- QuickTime animation of co-orbital motion from Murray and Dermott

- Cassini Observes the Orbital Dance of Epimetheus and Janus The Planetary Society

- A Search for Trojan Planets Web page of group of astronomers searching for extrasolar trojan planets at Appalachian State University