Clue (film)

| Clue | |

|---|---|

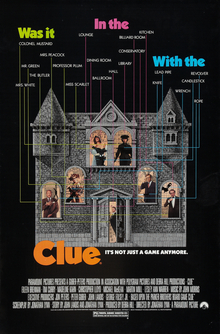

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jonathan Lynn |

| Screenplay by | Jonathan Lynn |

| Story by |

|

| Based on | Cluedo by Anthony E. Pratt |

| Produced by | Debra Hill |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Victor J. Kemper |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | John Morris |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 97 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million |

| Box office | $14.6 million |

Clue is a 1985 American black comedy mystery film based on the board game of the same name. Directed by Jonathan Lynn, who co-wrote the script with John Landis, and produced by Debra Hill, it stars the ensemble cast of Eileen Brennan, Tim Curry, Madeline Kahn, Christopher Lloyd, Michael McKean, Martin Mull, and Lesley Ann Warren, with Colleen Camp and Lee Ving in supporting roles.

Inspired by the nature of the board game, the film has multiple different endings. Originally screening one of three possibilities at different theaters, home media releases include all three endings. The film initially received mixed reviews and performed poorly at the box office, grossing $14.6 million in the United States against its budget of $15 million,[2] but later developed a considerable cult following.[3][4]

Plot

[edit]In 1954, six strangers are invited to a secluded New England mansion. Greeted by the butler Wadsworth and the maid Yvette, each guest receives a pseudonym to maintain confidentiality: "Colonel Mustard", "Mrs. White", "Mrs. Peacock", "Mr. Green", "Professor Plum", and "Miss Scarlet". During dinner, they discover they all hold government influence before being joined by Mr. Boddy, who has been blackmailing everyone for some time. Wadsworth has called the police to arrest Boddy, but Boddy threatens to expose everyone's secrets if they turn him in. He then presents the six guests with weapons—a candlestick, rope, lead pipe, wrench, revolver, and dagger—and suggests someone kill Wadsworth to protect their secrets before turning out the lights. After a gunshot rings out, Boddy is found on the floor, seemingly dead.

As the guests investigate Boddy's death, Wadsworth explains how he became indentured to Boddy and summoned the guests, hoping to force a confession from Boddy and turn him over to the police. As the group suspect the cook, only to find she was fatally stabbed with the dagger, someone discovers Boddy is alive before killing him with the candlestick. Wadsworth locks the weapons in a cupboard, but before he can throw away the key, a stranded motorist arrives and Wadsworth locks him in the lounge before throwing a key out the front door. The group draw lots to pair up before searching the manor. However, someone burns the blackmail evidence, unlocks the cupboard, and kills the motorist with the wrench. Discovering a secret passage, Mustard and Scarlet find themselves locked in the lounge with the motorist's corpse. When they scream for help, Yvette shoots the door open with the revolver. The group deduce that Wadsworth threw out the wrong key and the murderer pickpocketed the cupboard key from him.

A cop investigating the motorist's abandoned car arrives to use the phone. The mansion receives a call from FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover, which Wadsworth takes alone. After successfully distracting the cop and concealing the bodies, the group resumes their search until someone turns off the electricity. In the darkness, Yvette, the cop, and an arriving singing telegram girl are murdered with the rope, pipe, and revolver, respectively. Wadsworth restores the power and gathers the group, having deduced what happened. Recreating the night's events and amidst a brief interruption from an evangelist, he explains how the other five victims were Boddy's informants who are each connected to one of the guests, which dovetails into one of three possible outcomes.

"How It Could Have Happened"

[edit]Yvette murdered the cook and Boddy under orders from Scarlet, who then killed her and the other victims. Intending to sell the guests' secrets, Scarlet prepares to use the revolver to kill Wadsworth, who argues there are no bullets left before disarming her just as law enforcement raid the manor and the evangelist is revealed to be the chief of police. Wadsworth further reveals he is an undercover FBI agent before accidentally firing the last bullet in the revolver at a chandelier, which narrowly misses Mustard as it falls.

"How About This?"

[edit]Peacock killed all the victims to prevent her exposure for taking bribes from foreign powers before holding the others at gunpoint to escape. To the others' confused relief, Wadsworth reveals he is an undercover FBI agent. Peacock is arrested outside before law enforcement raid the manor and the evangelist is revealed to be the chief of police.

"Here's What Really Happened"

[edit]Apart from Green, everyone committed a single murder: Peacock killed the cook, Plum killed Boddy, Mustard killed the motorist, Scarlet killed the cop, White killed Yvette, and Wadsworth killed the singing telegram girl. Holding the guests at gunpoint, Wadsworth reveals he is actually the real Mr. Boddy (previously faked by his butler), and announces his intent to continue blackmailing them. Green swiftly draws his own revolver and kills Wadsworth/Boddy. Green reveals he is an undercover FBI agent sent to investigate Boddy; the evangelist is revealed to be the chief of police, and law enforcement proceeds to arrest all the remaining suspects.

Cast

[edit]

- Eileen Brennan as Mrs. Peacock, the wife of a U.S. senator who has been accepting bribes from foreign powers

- Tim Curry as Wadsworth, a butler who once worked for Mr. Boddy and seeks justice for his wife yet is revealed to be the real Mr. Boddy in one of the endings.

- Madeline Kahn as Mrs. White, the widow of a nuclear physicist and four previous men, all of whom died under suspicious circumstances

- Christopher Lloyd as Professor Plum, a disgraced former psychiatrist working for the World Health Organization

- Michael McKean as Mr. Green, a State Department employee and a closeted homosexual which, in one of the endings, is revealed to be part of his cover as an FBI agent, and that he is actually married to a woman.

- Martin Mull as Colonel Mustard, an army officer guilty of war profiteering

- Lesley Ann Warren as Miss Scarlet, a sassy Washington, D.C. madam

- Colleen Camp as Yvette, a voluptuous French maid who formerly worked as a call girl for Miss Scarlet and had an affair with one of Mrs. White’s late husbands.

- Lee Ving as Mr. Boddy, a man who has been blackmailing the six guests and Wadsworth's wife yet is revealed in one of the endings to be the butler to the real Mr. Boddy who is actually Wadsworth.

- Bill Henderson as The Cop, a police officer whom Miss Scarlet had been bribing

- Jane Wiedlin as The Singing Telegram Girl, a former patient of Professor Plum, with whom she had an affair

- Jeffrey Kramer as The Motorist, Colonel Mustard's driver during World War II

- Kellye Nakahara as The Cook (Mrs. Ho), the former cook of Mr. Boddy and Mrs. Peacock

Additionally, Howard Hesseman makes an uncredited appearance as the Chief of Police who works undercover as an evangelist.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Producer Debra Hill initially acquired the rights to adapt the game from Parker Brothers and intended to distribute through Universal Pictures.[5] As early as 1981 Hill mentioned plans to adapt the game into a movie, with P. D. James reported to be writing the screenplay with multiple endings.[6]

Screenplay

[edit]The multiple-endings were developed by John Landis, who had initially been set to direct, and who claimed in an interview to have invited playwright Tom Stoppard, writer and composer Stephen Sondheim, and actor Anthony Perkins to write the screenplay. The script was ultimately finished by Jonathan Lynn, who was invited to direct as a result.[3][5]

A fourth ending was written for the film; according to Lynn, "It really wasn't very good. I looked at it, and I thought, 'No, no, no, we've got to get rid of that.'"[7] In the scrapped ending: Wadsworth committed all the murders, and reveals he poisoned the champagne, leaving no witnesses when the six guests soon die. The officers arrive and capture Wadsworth, but he breaks free and steals a police car, though his escape is ultimately thwarted when three police dogs lunge from the back seat.[8]

Casting

[edit]Carrie Fisher was originally cast to portray Miss Scarlet, but withdrew to enter treatment for drug and alcohol addiction; she was replaced with Lesley Ann Warren.[9][10] Jonathan Lynn's first choice for Wadsworth was Leonard Rossiter, but he died before filming commenced.[11] The second choice was Rowan Atkinson, but it was decided that he was not sufficiently well known at the time, so Tim Curry was cast.[11] The entire cast received the same salary and billing, despite their different levels of notability at the time.[5]

Filming

[edit]Clue was filmed on sound stages 17 and 18 at the Paramount Pictures film studios in Hollywood.[12] The set design is credited to Les Gobruegge, Gene Nollmanwas, and William B. Majorand, with set decoration by Thomas L. Roysden.[13][better source needed] To decorate the interior sets, authentic 18th- and 19th-century furnishings were rented from private collectors, including the estate of Theodore Roosevelt.[14] After completion, the set was bought by the producers of Dynasty, who used it as the fictional hotel The Carlton.

All interior scenes were filmed at the Paramount lot, except the ballroom scene. The ballroom, as well two driveway exteriors, were filmed on location at a mansion in South Pasadena, California. This site was destroyed in a fire on October 5, 2005.[15] The driveway and fountain were recreated on the Paramount lot and used for most shots, including the guests' arrivals. Exterior shots of the South Pasadena mansion were enhanced with matte paintings to make the house appear much larger; these were executed by matte artist Syd Dutton in consultation with Albert Whitlock.

Jonathan Lynn screened His Girl Friday for the cast as inspiration for how to deliver their lines.[5] Madeline Kahn improvised her monologue about "flames."[3]

Release

[edit]The film was released theatrically on December 13, 1985. Each theater received one of the three endings, and some theaters announced which ending the viewer would see.[16]

Novelizations

[edit]The novelization based on the screenplay is by Michael McDowell. Landis, Lynn, and Ann Matthews wrote the youth adaptation Clue: The Storybook. Published in 1985, both adaptations feature a fourth ending cut from the film:[17] in a variation on the-butler-did-it trope, Wadsworth explains how he killed Boddy and the other victims, then reveals to the guests that they've all been poisoned, leaving no witnesses to his perfect crime. As Wadsworth proceeds to disable the phones, the police chief (having previously posed as an evangelist) returns with a squad of officers who disarm Wadsworth. He nonetheless manages to escape, and attempts to getaway in a police car, only to crash after Dobermanns attack from the back seat.[18][19]

Home media

[edit]The film was released to home video for both VHS and Betamax videocassette formats in Canada and the United States on August 20, 1986, and to other countries on February 11, 1991.[12] It was released on DVD by Paramount Home Entertainment in June 17, 2000,[20] and on Blu-ray by Paramount Home Media Distribution on August 7, 2012.[21]

On December 12, 2023, Shout! Factory released a 4K UHD Blu-ray collector's edition of Clue. It includes new interviews with director Jonathan Lynn and production manager Jeffrey Chernov.[22]

The home video, television broadcasts, and on-demand streaming by services such as Netflix include all three endings shown sequentially, with the first two characterized as possible endings but the third being the only true one. All Blu-ray and DVD versions offer viewers the option to watch the endings separately (chosen randomly by the player), as well as the "home entertainment version" ending with all three of them stitched together.[23]

Soundtrack

[edit]La-La Land Records released the John Morris score for the film as a limited-edition CD soundtrack in February 2011.[24] For the film's 30th anniversary in 2015, Mondo issued a limited-edition 180-gram vinyl pressed on six different character-themed color variants.[25] A vinyl reissue from Enjoy The Ride Records followed in 2022.

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]The film initially received mixed reviews. Janet Maslin of The New York Times panned it, writing that the beginning "is the only part of the film that is remotely engaging. After that, it begins to drag".[26] Similarly, Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film 2.5 out of 4 stars, writing, "Clue offers a few big laughs early on followed by a lot of characters running around on a treadmill to nowhere."[27] Siskel particularly criticized the decision to release the film to theaters with three separate endings, calling it a "gimmick" that would distract audiences from the rest of the film, and concluding, "Clue is a movie that needs three different middles rather than three different endings."[27]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film 2 out of 4 stars, writing that it has a "promising" cast but the "screenplay is so very, very thin that [the actors] spend most of their time looking frustrated, as if they'd just been cut off right before they were about to say something interesting."[16] On Siskel & Ebert & the Movies, both agreed that the "A" ending was the best while the "C" ending was the worst.[28]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 72% based on 39 reviews, with an average rating of 6.4/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "A robust ensemble of game actors elevate Clue above its schematic source material, but this farce's reliance on novelty over organic wit makes its entertainment value a roll of the dice."[20] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 41 out of 100 based on 17 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[29]

Box office

[edit]Clue has grossed $14.6 million in North America, just short of its $15 million budget.[2]

Remake

[edit]Hasbro Entertainment established deals in April 2024 with TriStar Pictures and Sony Pictures Television for new screen adaptations of the board game.[30][31] Screenwriter Shay Hatten has been in talks for the new film script.[32][33]

Previous plans for a remake or reboot have languished for years. Initially Gore Verbinski was developing a new Clue film in 2009,[34] which was dropped by Universal Studios in 2011.[35] Hasbro Studios moved the project to 20th Century Fox by August 2016, envisioned as a "worldwide mystery" with action-adventure elements, potentially establishing a franchise with international appeal.[36] Ryan Reynolds optioned a three-year first-look deal in January 2018, planning to star in the remake, with a script by Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick.[37] Jason Bateman was briefly attached to the film in September 2019,[38] followed by James Bobin attached as director in February 2020,[39] with Oren Uziel hired to rewrite the script in August 2022.[40] Hasbro sought new rights deals for Clue in February 2024.[41]

Stage adaptations

[edit]The screenplay for the film was adapted for stage performances in 2017 by the original screenwriter Jonathan Lynn.[3][42] The stage production of Clue premiered in 2017 at Bucks County Playhouse, adapted by Hunter Foster with additional material by Eric Price. It was directed by Foster and starred Sally Struthers and Erin Dilly.[43] A revised adaptation by Sandy Rustin, incorporating material from Foster and Price, was first performed in 2020. Rustin's adaptation was described as "a welcome throwback to an era of physical comedy".[44] The stage adaptations have been performed widely.[45]

A national tour of the mystery-comedy play launched in 2024, directed by Casey Hushion.[46][47]

In other media

[edit]- The 2010 Family Guy episode "And Then There Were Fewer" parodies Clue alongside elements of Agatha Christie's And Then There Were None.

- The 2011 Adventure Time episode "The Creeps" sees Finn and company as guests to a mysterious masquerade hosted by a homicidal ghost in a spoof of the film.

- The 2012 CSI: NY episode "Clue: SI" makes several references to the film and game.

- The 2013 Psych episode "100 Clues" features Clue stars Martin Mull, Christopher Lloyd, and Lesley Ann Warren as suspects in a series of murders at a mansion. The episode, in addition to many jokes and themes in homage to the film, includes multiple endings in which the audience (separately for East and West Coast viewership) decides who is the real killer. The episode was dedicated to the memory of Madeline Kahn.[48]

- The 2014 Odd Squad episode "Crime at Shapely Manor" parodies Clue with a crime taking place at a mansion and characters having names including Lord Rectangle, Professor Square, Miss Triangle and Professor Pentagon.

- Writer-director Jonathan Lynn recorded a feature-length commentary for the film, independently produced by writer and devoted Clue fan Joshua Brandon. First released on episode 377 of the SModcast with Kevin Smith on June 17, 2017, the director's audio commentary has been distributed on multiple popular platforms.

- Warren guest starred on a 2019 episode of Mull's sitcom The Cool Kids as a love interest for his character. Her role announcement in November 2018 was initially touted by the press as a Clue reunion, though only Mull and Warren appear.[49]

- The retrospective tribute film Who Done It: The Clue Documentary debuted in November 2022, followed by an ETR Media Blu-ray release in February 2023, then streaming on Screambox in August 2023. The film details the making of Clue and its rise to cult status, based on interviews with surviving cast and crew.[50]

References

[edit]- ^ "Clue". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ a b "Clue (1985)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Vary, Adam B. (December 10, 2015). "Something Terrible Has Happened Here: The Crazy Story of How 'Clue' Went from Forgotten Flop to Cult Triumph". BuzzFeed. Archived from the original on July 25, 2024. Retrieved August 5, 2024.

That a high-concept, fast-talking farce based on a board game was a box office bomb in 1985 is no huge mystery. But figuring out how it became an enduring favorite is a Hollywood whodunit for the ages. (The prime suspect: you, in the living room, with the remote control.)

- ^ Frank, Priscilla (August 6, 2015). "30 Years Later and 'Clue' the Movie Is Still a Work of Cult Genius". HuffPost. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Farber, Stephen (August 25, 1985). "OFF THE BOARD, ONTO THE SCREEN FOR CLUE". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Freedman, Richard (October 30, 1981). "Double Bill: Tonight's 'Halloween' horrorthon based on writer's teen memories". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ Farr, Nick (March 13, 2012). "Abnormal Interviews: My Cousin Vinny Director Jonathan Lynn". Abnormal Use. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- ^ Matthews, Landis & Lynn 1985, pp. 57–59.

- ^ "Bad Movies We Love: Clue". Movieline. December 14, 2011. Archived from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ "An oral history of 'Clue,' the classic whodunnit". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ a b Jackson, Matthew (April 1, 2016). "13 Mysterious Facts About Clue". Mental Floss. Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Hatch, John (November 7, 2023). "What Do You Mean, Murder?" Clue and the Making of a Cult Classic. Fayetteville Mafia Press. ISBN 978-1949024609.

- ^ "Full cast and crew for Clue (1985)". IMDb. Archived from the original on January 5, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ^ "Clue (1985) Movie Filming Locations". The 80s Movies Rewind. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ "Photos from Filming Location – 2003". The Art of Murder. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (December 12, 1985). "Clue". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on May 12, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2014 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ Matthews, Landis & Lynn 1985.

- ^ McDowell, Michael (1985). Paramount Pictures Presents Clue. New York: Fawcett Gold Medal. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-4491-3049-0.

- ^ Matthews, Landis & Lynn 1985, p. 61.

- ^ a b "Clue Movie Reviews, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. December 13, 1985. Archived from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- ^ Katz, Josh (January 18, 2012). "Paramount Teases Four Upcoming Blu-ray Releases". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- ^ "Clue Collector's Edition". Shout! Factory. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^ "Clue Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ "Clue: The Movie: Limited Edition". La-La Land Records. Archived from the original on February 4, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ "Clue: The Movie – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack LP". Mondo. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (December 13, 1985). "Screen: 'Clue,' from Game to Film". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 22, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- ^ a b Siskel, Gene (December 13, 1985). "Did The Butler Do It? Clue Offers 3 Answers". Chicago Tribune. p. A. Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ Siskel, Gene; Ebert, Roger (December 1985). "At the Movies with Siskel & Ebert". Archived from the original on June 20, 2020. Retrieved December 9, 2018 – via YouTube.

The best ending...is "A"...stay away from the worst which is "C".

- ^ "Clue Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on September 28, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ Galuppo, Mia (April 23, 2024). "Clue Film and TV Rights Land at Sony". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ Otterson, Joe (April 23, 2024). "'Clue' Film, TV Adaptations in the Works Under New Deal Between Hasbro and Sony". Variety. Retrieved May 19, 2024.

- ^ Outlaw, Kofi (September 18, 2024). "Clue Movie Reboot Gets Major Update With the Perfect Director". ComicBook.com. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ Ruimy, Jordan (September 23, 2024). "Zach Cregger to Direct 'Resident Evil' Reboot; Exits 'Clue' Movie". World of Reel. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (February 24, 2009). "Gore Verbinski to develop 'Clue'". Variety. Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- ^ Rich, Katey (August 3, 2011). "Clue Movie Dropped By Universal, But Hasbro Is Still Making It On Their Own". CinemaBlend. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2011.

- ^ Lyons, Josh (August 16, 2016). "20th Century Fox Gets A "Clue" And Will Produce Classic Board Game Remake With Hasbro (EXCLUSIVE)". The Tracking Board. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ McNary, Dave (January 22, 2018). "Ryan Reynolds Signs First-Look Deal at Fox With 'Clue' Movie in the Works". Variety. Archived from the original on January 25, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ Welk, Brian (September 25, 2019). "Jason Bateman in Talks to Direct and Star in 'Clue' Reboot With Ryan Reynolds". TheWrap. Archived from the original on September 26, 2019. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (February 10, 2020). "James Bobin In Talks To Direct 'Clue' Movie At 20th Century". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on February 11, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (August 23, 2022). "Oren Uziel Stepping In To Write Ryan Reynolds 'Clue' Movie At 20th Century Studios". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- ^ Bolt, Neil (February 19, 2024). "Hasbro Shopping Rights to a New Clue Movie". ComingSoon.net. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ Cox, Gordon (October 11, 2016). "'Clue' on Stage: Play by Movie's Writer-Director to Bow in 2017 (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ ""Clue: On Stage" Premieres at Bucks County Playhouse in New Hope May 2". New Hope Free Press. 2017. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ Ramírez, Juan A. (February 8, 2022). "'Clue' Review: A Whodunit That Looks a Lot Like a Board Game". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 16, 2022. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ Weinert-Kendt, Rob (September 23, 2022). "'Clyde's' Is Most-Produced Play, and Lynn Nottage Most-Produced Playwright, of 2022-23 Season". American Theater.

- ^ Cullwell-Block, Logan. "Clue Will Embark on National Tour in 2024". Playbill.com. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ Rabinowitz, Chloe (April 9, 2024). "CLUE North American Tour". Broadway World. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ McFarland, Kevin (May 28, 2013). "Psych: "100 Clues"". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- ^ Swift, Andy (November 9, 2018). "The Cool Kids Staging Clue Reunion With Lesley Ann Warren, Martin Mull". TVLine. Archived from the original on November 10, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- ^ Smith, Jeff C. (October 13, 2018). "Who Done It: The Clue Documentary". IMDb. It Looks So Fake Productions. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Matthews, Ann; Landis, John; Lynn, Jonathan (1985). Paramount Pictures Presents Clue: The Storybook. New York: Little Simon. ISBN 978-0-6716-1867-4. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017.

External links

[edit]- Clue at IMDb

- Clue at AllMovie

- Clue at Box Office Mojo

- Clue at Rotten Tomatoes

- Clue at the TCM Movie Database

- Clue at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- An oral history of mystery classic Clue (2023)

- 1985 films

- Cluedo

- 1985 crime films

- 1985 directorial debut films

- 1985 thriller films

- 1980s American films

- 1985 black comedy films

- 1980s comedy mystery films

- 1980s comedy thriller films

- 1980s crime comedy films

- 1985 crime thriller films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s mystery thriller films

- American black comedy films

- American comedy mystery films

- American comedy thriller films

- American crime comedy films

- American crime thriller films

- American mystery thriller films

- English-language black comedy films

- English-language comedy mystery films

- English-language comedy thriller films

- English-language crime comedy films

- English-language crime thriller films

- English-language mystery thriller films

- Fiction with multiple endings

- Films about adultery in the United States

- Films about McCarthyism

- Films based on games

- Films based on Hasbro toys

- Films directed by Jonathan Lynn

- Films produced by Debra Hill

- Films scored by John Morris

- Films set in 1954

- Films set in country houses

- Films set in New England

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films with screenplays by John Landis

- Films with screenplays by Jonathan Lynn

- Murder mystery films

- Paramount Pictures films

- PolyGram Filmed Entertainment films